The Response of Russian Security Prices to Economic Sanctions: Policy Effectiveness and Transmission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Waves" of the Russia's Presidential Reforms Break About Premier's "Energy-Rocks"

AFRICA REVIEW EURASIA REVIEW "Waves" of the Russia's Presidential Reforms Break About Premier's "Energy-Rocks" By Dr. Zurab Garakanidze* Story about the Russian President Dmitry Medvedev’s initiative to change the make-up of the boards of state-owned firms, especially energy companies. In late March of this year, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev demanded that high-ranking officials – namely, deputy prime ministers and cabinet-level ministers that co-ordinate state policy in the same sectors in which those companies are active – step down from their seats on the boards of state-run energy companies by July 1. He also said that October 1 would be the deadline for replacing these civil servants with independent directors. The deadline has now passed, but Medvedev‟s bid to diminish the government‟s influence in the energy sector has run into roadblocks. Most of the high-level government officials who have stepped down are being replaced not by independent managers, but by directors from other state companies in the same sector. Russia‟s state-owned oil and gas companies have not been quick to replace directors who also hold high-ranking government posts, despite or- ders from President Dmitry Medvedev. High-ranking Russian officials have made a show of following President Medvedev‟s order to leave the boards of state-run energy companies, but government influence over the sector remains strong. This indicates that the political will needed for the presidential administration to push eco- nomic reforms forward may be inadequate. 41 www.cesran.org/politicalreflection Political Reflection | September-October-November 2011 Russia's Presidential Reforms | By Dr. -

Company News SECURITIES MARKET NEWS

SSEECCUURRIIITTIIIEESS MMAARRKKEETT NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR weekly Presented by: VTB Bank, Custody April 5, 2018 Issue No. 2018/12 Company News Commercial Port of Vladivostok’s shares rise 0.5% on April 3, 2018 On April 3, 2018 shares of Commercial Port of Vladivostok, a unit of Far Eastern Shipping Company (FESCO) of Russian multi-industry holding Summa Group, rose 0.48% as of 10.12 a.m. Moscow time after a 21.72% slump on April 2. On March 31, the Tverskoi District Court of Moscow sanctioned arrest of brothers Ziyavudin and Magomed Magomedov, co-owners of Summa Group, on charges of RUB 2.5 bln embezzlement. It also arrested Artur Maksidov, CEO of Summa’s construction subsidiary Inteks, on charges of RUB 669 mln embezzlement. On April 2, shares of railway container operator TransContainer, in which FESCO owns 25.07%, fell 0.4%, and shares of Novorossiysk Commercial Sea Port (NCSP), in which Summa and oil pipeline monopoly Transneft own 50.1% on a parity basis, lost 1.61%. Cherkizovo plans common share SPO, to change dividends policy On April 3, 2018 it was reported that meat producer Cherkizovo Group would hold a secondary public offering (SPO) of common shares on the Moscow Exchange to raise USD 150 mln and change the dividend policy to pay 50% of net profit under International Financial Reporting Standards. The shares grew 1.67% to RUB 1,220 as of 10:25 a.m., Moscow time, on the Moscow Exchange. Under the proposal, the current shareholders, including company MB Capital Europe Ltd, whose beneficiaries are members of the Mikhailov- Babayev family (co-founders of the group), will sell shares. -

FY2020 Financial Results

Norilsk Nickel 2020 Financial Results Presentation February 2021 Disclaimer The information contained herein has been prepared using information available to PJSC MMC Norilsk Nickel (“Norilsk Nickel” or “Nornickel” or “NN”) at the time of preparation of the presentation. External or other factors may have impacted on the business of Norilsk Nickel and the content of this presentation, since its preparation. In addition all relevant information about Norilsk Nickel may not be included in this presentation. No representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information. Any forward looking information herein has been prepared on the basis of a number of assumptions which may prove to be incorrect. Forward looking statements, by the nature, involve risk and uncertainty and Norilsk Nickel cautions that actual results may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements. Reference should be made to the most recent Annual Report for a description of major risk factors. There may be other factors, both known and unknown to Norilsk Nickel, which may have an impact on its performance. This presentation should not be relied upon as a recommendation or forecast by Norilsk Nickel. Norilsk Nickel does not undertake an obligation to release any revision to the statements contained in this presentation. The information contained in this presentation shall not be deemed to be any form of commitment on the part of Norilsk Nickel in relation to any matters contained, or referred to, in this presentation. Norilsk Nickel expressly disclaims any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the contents of this presentation. -

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the Registrar of the Company and the Acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the registrar of the Company and the acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel IRC – R.O.S.T. (former R.O.S.T. Registrar merged with Independent Registrar Company in February 2019) was established in 1996. In 2003–2015, Independent Registrar Company was a member of Computershare Group, a global leader in registrar and transfer agency services. In July 2015, IRC changed its ownership to pass into the control of a group of independent Russian investors. In December 2016, R.O.S.T. Registrar and Independent Registrar Company, both owned by the same group of independent investors, formed IRC – R.O.S.T. Group of Companies. In 2018, Saint Petersburg Central Registrar joined the Group. In February 2019, Independent Registrar Company merged with IRC – R.O.S.T. Ultimate beneficiaries of IRC – R.O.S.T. Group are individuals with a strong background in business management and stock markets. No beneficiary holds a blocking stake in the Group. In accordance with indefinite License No. 045-13976-000001, IRC – R.O.S.T. keeps records of holders of registered securities. Services offered by IRC – R.O.S.T. to its clients include: › Records of shareholders, interestholders, bondholders, holders of mortgage participation certificates, lenders, and joint property owners › Meetings of shareholders, joint owners, lenders, company members, etc. › Electronic voting › Postal and electronic mailing › Corporate consulting › Buyback of securities, including payments for securities repurchased › Proxy solicitation › Call centre services › Depositary and brokerage, including escrow agent services IRC – R.O.S.T. Group invests a lot in development of proprietary high-tech solutions, e.g. -

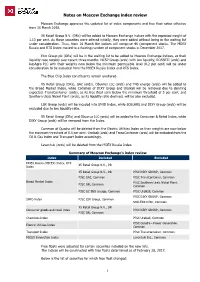

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

Annual Report

2014 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Sistema today 2 Corporate governance system 91 History timeline 4 Corporate governance principles 92 Company structure 8 General Meeting of shareholders 94 President’s speech 10 Board of Directors 96 Strategic Review 11 Commitees of the Board of Directors 99 Strategy 12 President and the Management Board 101 Sistema’s financial results 20 Internal control and audit 103 Shareholder capital and securities 24 Development of the corporate 104 governance system in 2014 Our investments 27 Remuneration 105 MTS 28 Risks 106 Detsky Mir 34 Sustainable development 113 Medsi Group 38 Responsible investor 114 Lesinvest Group (Segezha) 44 Social investment 115 Bashkirian Power Grid Company 52 Education, science, innovation 115 RTI 56 Culture 117 SG-trans 60 Environment 119 MTS Bank 64 Society 121 RZ Agro Holding 68 Appendices 124 Targin 72 Binnopharm 76 Real estate 80 Sistema Shyam TeleServices 84 Sistema Mass Media 88 1 SISTEMA TODAY Established in 1993, today Sistema including telecommunications, companies. Sistema’s competencies is a large private investor operating utilities, retail, high tech, pulp and focus on improvement of the in the real sector of the Russian paper, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, operational efficiency of acquired economy. Sistema’s investment railway transportation, agriculture, assets through restructuring and portfolio comprises stakes in finance, mass media, tourism, attracting industry partners to predominantly Russian companies etc. Sistema is the controlling enhance expertise and reduce -

Tatneft Group IFRS CONSOLIDATED INTERIM CONDENSED

Tatneft Group IFRS CONSOLIDATED INTERIM CONDENSED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS (UNAUDITED) AS OF AND FOR THE THREE AND SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2019 Contents Report on Review of Consolidated Interim Condensed Financial Statements Consolidated Interim Condensed Financial Statements Consolidated Interim Condensed Statement of Financial Position (unaudited) ........................................ 1 Consolidated Interim Condensed Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income (unaudited) ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Consolidated Interim Condensed Statement of Changes in Equity (unaudited) ........................................ 4 Consolidated Interim Condensed Statement of Cash Flows (unaudited) .................................................. 5 Notes to the Consolidated Interim Condensed Financial Statements (unaudited) Note 1: Organisation ................................................................................................................................. 7 Note 2: Basis of preparation ...................................................................................................................... 7 Note 3: Adoption of new or revised standards and interpretations .......................................................... 10 Note 4: Cash and cash equivalents .......................................................................................................... 12 Note 5: Accounts receivable ................................................................................................................... -

Russia Intelligence

N°70 - January 31 2008 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS SPOTLIGHT P. 1-3 Politics & Government c Medvedev’s Last Battle Before Kremlin Debut SPOTLIGHT c Medvedev’s Last Battle The arrest of Semyon Mogilevich in Moscow on Jan. 23 is a considerable development on Russia’s cur- Before Kremlin Debut rent political landscape. His profile is altogether singular: linked to a crime gang known as “solntsevo” and PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS sought in the United States for money-laundering and fraud, Mogilevich lived an apparently peaceful exis- c Final Stretch for tence in Moscow in the renowned Rublyovka road residential neighborhood in which government figures « Operation Succession » and businessmen rub shoulders. In truth, however, he was involved in at least two types of business. One c Kirillov, Shestakov, was the sale of perfume and cosmetic goods through the firm Arbat Prestige, whose manager and leading Potekhin: the New St. “official” shareholder is Vladimir Nekrasov who was arrested at the same time as Mogilevich as the two left Petersburg Crew in Moscow a restaurant at which they had lunched. The charge that led to their incarceration was evading taxes worth DIPLOMACY around 1.5 million euros and involving companies linked to Arbat Prestige. c Balkans : Putin’s Gets His Revenge The other business to which Mogilevich’s name has been linked since at least 2003 concerns trading in P. 4-7 Business & Networks gas. As Russia Intelligence regularly reported in previous issues, Mogilevich was reportedly the driving force behind the creation of two commercial entities that played a leading role in gas relations between Russia, BEHIND THE SCENE Turkmenistan and Ukraine: EuralTransGaz first and then RosUkrEnergo later. -

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals After the Crisis: Results of 2011

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals after the Crisis: Results of 2011 Report dated April 16, 2013 Moscow and New York, April 16, 2013 The Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, and the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment (VCC), a joint center of Columbia Law School and the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York, are releasing the results of their third survey of Russian multinationals today.1 The survey, conducted from November 2012 to February 2013, is part of a long-term study of the global expansion of emerging market non-financial multinational enterprises (MNEs).2 The present report covers the period 2009-2011. Highlights Russia is one of the leading emerging markets in terms of outward foreign direct investments (FDI). Such a position is supported not by several multinational giants but by dozens of Russian MNEs in various industries. Foreign assets of the top 20 Russian non-financial MNEs grew every year covered by this report and reached US$ 111 billion at the end of 2011 (Table 1). Large Russian exporters usually use FDI in support of their foreign activities. As a result, oil and gas and steel companies with considerable exports are among the leading Russian MNEs. However, representatives of other industries also have significant foreign assets. Many companies remained “regional” MNEs. As a result, more than 66% of the ranked companies’ foreign assets were in Europe and Central Asia, with 28% in former republics of the Soviet Union (Annex table 2). Due to the popularity of off-shore jurisdictions to Russian MNEs, some Caribbean islands and Cyprus attracted many Russian subsidiaries with low levels of foreign assets. -

HEDGE EFFECTIVENESS of the RTS INDEX FUTURES Anastasia Musorgina a Thesis Submitted to the University of North Carolina in Part

HEDGE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE RTS INDEX FUTURES Anastasia Musorgina A Thesis Submitted to the University of North Carolina in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration Cameron School of Business University of North Carolina Wilmington 2011 Approved by Advisory Committee Nivine Richie Rob Burrus Cetin Ciner Chair Accepted by _____________________________ Dean, Graduate School TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. iii DEDICATION .......................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. vii INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 1 Hedging .................................................................................................................................. 1 Russian Derivatives Market ................................................................................................... 2 Moscow Interbank Currency Exchange ................................................................................ -

Tender Offer Memorandum Polyus Service Limited

TENDER OFFER MEMORANDUM POLYUS SERVICE LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (A WHOLLY-OWNED SUBSIDIARY OF PUBLIC JOINT STOCK COMPANY POLYUS) with respect to a proposed tender offer to purchase for cash up to 317,792 of the issued and outstanding ordinary shares, of RUB 1 nominal value per share (“Ordinary Shares”), including Ordinary Shares represented by Regulation S and Rule 144A Global Depositary Shares (“GDSs”) and Level I American Depositary Shares (“ADSs” and, together with GDSs, “DSs”), with two GDSs or two ADSs representing one Ordinary Share, of PUBLIC JOINT STOCK COMPANY POLYUS at a purchase price not less than US$210.00 and not greater than US$240.00 per each Ordinary Share and not less than US$105.00 and not greater than US$120.00 per each DS THIS TENDER OFFER WILL EXPIRE AT 4:00 P.M., LUXEMBOURG/BRUSSELS TIME (6:00 P.M., MOSCOW TIME, 3:00 P.M., LONDON TIME, 10:00 A.M., NEW YORK TIME) ON DECEMBER 24, 2020, UNLESS THIS TENDER OFFER IS EXTENDED (THE “EXPIRATION TIME”). Please note that The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”), Euroclear Bank S.A./N.V. (“Euroclear”) and Clearstream Banking, société anonyme (“Clearstream” and, together with DTC and Euroclear, the “Clearing Systems”), their respective participants and the brokers or other securities intermediaries through which DSs are held will establish their own cut-off dates and times for the tender of the DSs, which will be earlier than the Expiration Time. THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. THE TENDER OFFER AS SET OUT IN THIS TENDER OFFER MEMORANDUM IS SUBJECT -

Templeton Eastern Europe Fund Equity LU0078277505 31 August 2021

Franklin Templeton Investment Funds Emerging Markets Templeton Eastern Europe Fund Equity LU0078277505 31 August 2021 Fund Fact Sheet For professional use only. Not for distribution to the public. Fund Overview Performance Base Currency for Fund EUR Performance over 5 Years in Share Class Currency (%) Templeton Eastern Europe Fund A (acc) EUR MSCI EM Europe Index-NR Total Net Assets (EUR) 231 million Fund Inception Date 10.11.1997 160 Number of Issuers 45 Benchmark MSCI EM Europe 140 Index-NR Investment Style Blend Morningstar Category™ Emerging Europe Equity 120 Summary of Investment Objective 100 The Fund aims to achieve long-term capital appreciation by investing primarily in listed equity securities of issuers organised under the laws of or having their principal activities within the countries of Eastern Europe, as well as 80 08/16 02/17 08/17 02/18 08/18 02/19 08/19 02/20 08/20 02/21 08/21 the New Independent States, i.e. the countries in Europe and Asia that were formerly part of or under the influence of Performance in Share Class Currency (%) the Soviet Union. Cumulative Annualised Since Since Fund Management 1 Mth 3 Mths 6 Mths YTD 1 Yr 3 Yrs 5 Yrs 10 Yrs Incept Incept A (acc) EUR 6.42 11.11 26.64 33.63 51.24 53.18 56.89 34.32 260.58 5.54 Krzysztof Musialik, CFA: Poland A (acc) USD 5.94 7.30 23.95 29.16 49.67 55.85 66.03 10.37 25.43 1.44 Ratings - A (acc) EUR B (acc) USD 5.87 6.92 23.29 28.09 47.85 50.20 56.08 -2.95 -24.30 -1.84 Benchmark in EUR 5.12 10.50 24.75 24.42 37.82 37.48 54.51 30.76 271.45 5.67 Overall Morningstar Rating™: Calendar Year Performance in Share Class Currency (%) Asset Allocation 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 A (acc) EUR -15.33 36.67 -21.23 17.61 20.37 4.84 -19.49 -3.97 17.37 -40.02 A (acc) USD -7.78 33.81 -24.78 34.11 16.61 -5.88 -29.18 0.07 19.63 -41.94 B (acc) USD -8.80 31.98 -25.72 32.46 14.98 -7.07 -30.09 -1.33 18.15 -42.70 Benchmark in EUR -19.73 34.75 -7.46 5.88 29.27 -5.03 -20.28 -8.61 22.37 -21.10 % Past performance is not an indicator or a guarantee of future performance.