Nepal General Evaluation 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Resources of Nepal in the Context of Climate Change

Government of Nepal Water and Energy Commission Secretariat Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal WATER RESOURCES OF NEPAL IN THE CONTEXT OF CLIMATE CHANGE 2011 Water Resources of Nepal in the Context of Climate Change 2011 © Water and Energy Commission Secretariat (WECS) All rights reserved Extract of this publication may be reproduced in any form for education or non-profi t purposes without special permission, provided the source is acknowledged. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purposes without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by: Water and Energy Commission Secretariat (WECS) P.O. Box 1340 Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Website: www.wec.gov.np Email: [email protected] Fax: +977-1-4211425 Edited by: Dr. Ravi Sharma Aryal Mr. Gautam Rajkarnikar Water and Energy Commission Secretariat Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Front cover picture : Mera Glacier Back cover picture : Tso Rolpa Lake Photo Courtesy : Mr. Om Ratna Bajracharya, Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, Ministry of Environment, Government of Nepal PRINTED WITH SUPPORT FROM WWF NEPAL Design & print : Water Communication, Ph-4460999 Water Resources of Nepal in the Context of Climate Change 2011 Government of Nepal Water and Energy Commission Secretariat Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal 2011 Water and its availability and quality will be the main pressures on, and issues for, societies and the environment under climate change. “IPCC, 2007” bringing i Acknowledgement Water Resource of Nepal in the Context of Climate Change is an attempt to show impacts of climate change on one of the important sector of life, water resource. Water is considered to be a vehicle to climate change impacts and hence needs to be handled carefully and skillfully. -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

Integrated Urban Development Project- Siddharthanagar Municipality

Draft Initial Environmental Examination September 2011 NEP: Integrated Urban Development Project- Siddharthanagar Municipality Prepared by the Government of Nepal, Ministry of Physical Planning and Works for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 5 August 2011) Currency unit – Nepalese rupee (NRs/NRe) NRs1.00 = $0.01391 $1.00 = NRs 71.874 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CBO - community building organization CLC - City Level Committees CPHEEO - Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organization CTE - Consent to Establish CTO - Consent to Operate DSMC - Design Supervision Management Consultant EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan GRC - Grievance Redress Committee H&S - health and safety IEE - initial environmental examination IPCC - Investment Program Coordination Cell lpcd - liters per capita per day MFF - Multitranche Financing Facility MSW - municipal solid waste NEA - national-level Executing Agency NGO - nongovernmental organization NSC - National level Steering Committee O&M - operation and maintenance PMIU - Project Management and Implementation Unit PSP - private sector participation SEA - State-level Executing Agency SEIAA - State Environment Impact Assessment Authority SIPMIU - State-level Investment Program Management and Implementation Units SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TOR - terms of reference UD&PAD - Urban Development & Poverty Alleviation Department UDD - Urban Development Department ULB - urban local body WEIGHTS AND MEASURES dbA – decibels ha – hectare km – kilometer km2 – square kilometer l – liter m – meter m2 – square meter M3 – cubic meter MT – metric tons MTD – metric tons per day NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Improving Maternal Health Services Through Social Accountability Interventions in Nepal: an Analytical Review of Existing Litera

Nepal et al. Public Health Reviews (2020) 41:31 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-020-00147-0 REVIEW Open Access Improving maternal health services through social accountability interventions in Nepal: an analytical review of existing literature Adweeti Nepal1* , Santa Kumar Dangol2 and Anke van der Kwaak3 * Correspondence: anepal7@gmail. com Abstract 1Save the Children, Surkhet, Karnali Province, Nepal Background: The persistent quality gap in maternal health services in Nepal has Full list of author information is resulted in poor maternal health outcomes. Accordingly, the Government of Nepal available at the end of the article (GoN) has placed emphasis on responsive and accountable maternal health services and initiated social accountability interventions as a strategical approach simultaneously. This review critically explores the social accountability interventions in maternal health services in Nepal and its outcomes by analyzing existing evidence to contribute to the informed policy formulation process. Methods: A literature review and desk study undertaken between December 2018 and May 2019. An adapted framework of social accountability by Lodenstein et al. was used for critical analysis of the existing literature between January 2000 and May 2019 from Nepal and other low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) that have similar operational context to Nepal. The literature was searched and extracted from database such as PubMed and ScienceDirect, and web search engines such as Google Scholar using defined keywords. Results: The study found various social accountability interventions that have been initiated by GoN and external development partners in maternal health services in Nepal. Evidence from Nepal and other LMICs showed that the social accountability interventions improved the quality of maternal health services by improving health system responsiveness, enhancing community ownership, addressing inequalities and enabling the community to influence the policy decision-making process. -

PNAAZ076.Pdf

July 1987 FOEWOD This Natural Resource Management Paper Serie is funded through the project, "Strengthenirv Institutional Capacity in the Food and Agricul tural Sector in Nepal," a cooperative effort by the Ministry of Agricul ture (MOA) of His Majesty's Government of lepal and the Winrock Interna tional Institute for Agricultural Development. This project has been :. ,;L, 'f : ;. -International made possible by substantial financial support from the U.S. Age'acy for >7 . " A HONG PASTURE, Development (USAID), the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ), the Canadian Interiiational Development Research Centre (IDRC), and the Ford Foundation. 2,1 C' ULY-.P One of the most important activities of this project is funding for problem-oriented research by young professional staff of agricultural C a se S t u d Ta ra agencies of the MOA and related institutions, as well as by concerned individials in the private sector. This research is carried out with the active profe~sional assistance of the Winrock staff, The purpose of this Natural Resource Management Paper Series is to make the results of the research Om Prasacd Guruna activizies related to natural resources available to a larger audience, and to acquaint younger staff and students with advanced methods of research and statistical analysis. It ia also hoped that publication of the Series will stimulate discussion among policymakers and thereby assist in the formulation of policies which are suitable to the development of Nepal's agrculture. The views expressed in this Researci Report Series are those of the authors, and do not necessarily ref lect the views of their respective parent institutions. -

Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning In

VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL IMPLEMENTING AGENCY IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS SUPPORTED BY Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation, Department of Forests UNE P Empowered lives. Resilient nations. VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL Copyright © 2015 Mountain EbA Project, Nepal The material in this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit uses, without prior written permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. We would appreciate receiving a copy of any product which uses this publication as a source. Citation: Dixit, A., Karki, M. and Shukla, A. (2015): Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning in Panchase Mountain Ecological Region, Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, United Nations Environment Programme, United Nations Development Programme, International Union for Conservation of Nature, German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal. ISBN : 978-9937-8519-2-3 Published by: Government of Nepal (GoN), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal (ISET-N). -

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy Andactionplan2016-2025|Chitwan-Annapurnalandscape,Nepal

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy andActionPlan2016-2025|Chitwan-AnnapurnaLandscape,Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1- 4211567, 4211936 Fax: +977-1-4223868 Website: www.mfsc.gov.np Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Publisher: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Citation: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation 2015. Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025, Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Cover photo credits: Forest, River, Women in Community and Rhino © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Snow leopard © WWF Nepal/ DNPWC Rhododendron © WWF Nepal Back cover photo credits: Forest, Gharial, Peacock © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Red Panda © Kamal Thapa/ WWF Nepal Buckwheat fi eld in Ghami village, Mustang © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kapil Khanal Women in wetland © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kashish Das Shrestha © Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Acronyms and Abbreviations ACA Annapurna Conservation Area asl Above Sea Level BZ Buffer Zone BZUC Buffer Zone User Committee CA Conservation Area CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAPA Community Adaptation Plans for Action CBO Community Based Organization CBS -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 27: 67-125 (2004)

Realities and Images of Nepal’s Maoists after the Attack on Beni1 Kiyoko Ogura 1. The background to Maoist military attacks on district head- quarters “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” – Mao Tse-Tung’s slogan grabs the reader’s attention at the top of its website.2 As the slogan indicates, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) has been giving priority to strengthening and expanding its armed front since they started the People’s War on 13 February 1996. When they launched the People’s War by attacking some police posts in remote areas, they held only home-made guns and khukuris in their hands. Today they are equipped with more modern weapons such as AK-47s, 81-mm mortars, and LMGs (Light Machine Guns) purchased from abroad or looted from the security forces. The Maoists now are not merely strengthening their military actions, such as ambushing and raiding the security forces, but also murdering their political “enemies” and abducting civilians, using their guns to force them to participate in their political programmes. 1.1. The initial stages of the People’s War The Maoists developed their army step by step from 1996. The following paragraph outlines how they developed their army during the initial period of three years on the basis of an interview with a Central Committee member of the CPN (Maoist), who was in charge of Rolpa, Rukum, and Jajarkot districts (the Maoists’ base area since the beginning). It was given to Li Onesto, an American journalist from the Revolutionary Worker, in 1999 (Onesto 1999b). -

Short Listed Candidates for the Post

.*,ffix ryryffi-ffiffiWffir@fuffir. rySW{Jrue,€ f,rc, "*,*$,S* S&s#ery W€ryff$,,,SffWryf ryAeW Notice for the Short Listed Candidates applying in the post of "Trainee Assistantrr Details fot Exam: a. 246lestha,2076: Collection of Entrance Card (For Surrounding Candidates). b. 25nJestha, 2076: Collection of Entrance Card 8:00AM to 9:45AM in Exam Center (For Others). (Please carry Original Citizenship Certificate and l passport size photo). Written Test (Exam) : Date : 25'hJesth, 2076 Saurday (8ftJune, 2019). Time : 10:00 AM to 11:30 AM tVenue : Oxford Higher Secondary School, Sukhkhanagar, Butwal, Rupandehi. Paper Weightage : 100 Marks Composition Subjective Questions : 02 questions @ 10 marks = 20 marks Objective Questions : 40 questions @ 02 marks = B0 marks Contents 1,. General Banking Information - 10 objective questions @ 2 marks = 20 marks 2. Basic Principles & Concept of Accounting - 10 objective questions @2marks = 20 marks 3. Quantitative Aptitude 10 objective questions @ 2 marks = 20 marks 4. General ISowledge - 10 objective questions @ 2 marks = 20 marks (2 Subjective questions shall be from the fields as mentioned above). NOTE: ,/ I(ndly visit Bank's website for result and interview notice. For Futther Information, please visit : Ffuman Resource Department Shine Resunga Development Bank Limited, Central Office, Maitri Path, But'ural. enblrz- *rrc-tr fffir tarmrnfrur *ffi ffi{" ggffrus gevrcgemmrup w mes'g:iwme ffiAru${ frffi. S4tq t:e w r4r4.q klc S.No. Name of Applicant Address 7 Aakriti Neupane Sainamaina-03, M u reiva RuoanriEh] -

Nepal: the Maoists’ Conflict and Impact on the Rights of the Child

Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi-110058, India Phone/Fax: +91-11-25620583; 25503624; Website: www.achrweb.org; Email: [email protected] Embargoed for: 20 May 2005 Nepal: The Maoists’ conflict and impact on the rights of the child An alternate report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child on Nepal’s 2nd periodic report (CRC/CRC/C/65/Add.30) Geneva, Switzerland Nepal: The Maoists’ conflict and impact on the rights of the child 2 Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 4 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................. 5 III. GENERAL PRINCIPLES .............................................................................. 15 ARTICLE 2: NON-DISCRIMINATION ......................................................................... 15 ARTICLE 6: THE RIGHT TO LIFE, SURVIVAL AND DEVELOPMENT .......................... 17 IV. CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS............................................................ 17 ARTICLE 7: NAME AND NATIONALITY ..................................................................... 17 Case 1: The denial of the right to citizenship to the Badi children. ......................... 18 Case 2: The denial of the right to nationality to Sikh people ................................... 18 Case 3: Deprivation of citizenship to Madhesi community ...................................... 18 Case 4: Deprivation of citizenship right to Raju Pariyar........................................ -

SASEC Road Improvement Project

Social Monitoring Report Semiannual Report (July-December 2018) January 2019 NEP: SASEC Road Improvement Project Prepared by Department of Roads, Project Directorate (ADB), for Ministry of Physical Infrastructure & Transport and the Asian Development Bank. This social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. pGovernment of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport DEPARTMENT OF ROADS Project Directorate (ADB) Bishalnagar, Kathmandu, Nepal CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR CONSTRUCTION SUPERVISION OF SASEC ROADS IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (SRIP) (ADB Loan No.: 3478-NEP) SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT NO. 3 (SOCIAL MONITORING) SASEC Roads Improvement Project Package 1: EWH- Narayanghat Butwal Road, Section I (64.425 Km) Package 2: EWH- Narayanghat Butwal Road, Section II (48.535 Km) Package 3: Bhairahawa – Lumbini - Taulihawa Road, (41.130 Km) (July - December) 2018 Submitted by M/S Korea Engineering Consultants Ltd. Corp.- MEH Consultant (P) Ltd., Kyong Dong Engineering Co. Ltd. JV In association with MULTI – Disciplinary Consultants (P) Ltd. & Seoul, Korea. SOIL Test (P) Ltd. SEMI-ANNUAL (SOCIAL MONITORING) REPORT 3 July - December 2018 Social Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report No. 3 (July - December 2018) NEP: Loan No. 3478 SASEC Road Improvement Project (SRIP) Prepared by: Department of Roads, Project Directorate (ADB), for Ministry of Physical Infrastructure & Transport and the Asian Development Bank. -

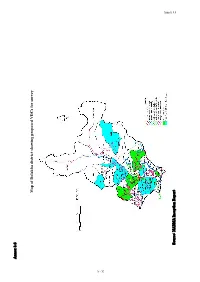

Map of Dolakha District Show Ing Proposed Vdcs for Survey

Annex 3.6 Annex 3.6 Map of Dolakha district showing proposed VDCs for survey Source: NARMA Inception Report A - 53 Annex 3.7 Annex 3.7 Summary of Periodic District Development Plans Outlay Districts Period Vision Objectives Priorities (Rs in 'ooo) Kavrepalanchok 2000/01- Protection of natural Qualitative change in social condition (i) Development of physical 7,021,441 2006/07 resources, health, of people in general and backward class infrastructure; education; (ii) Children education, agriculture (children, women, Dalit, neglected and and women; (iii) Agriculture; (iv) and tourism down trodden) and remote area people Natural heritage; (v) Health services; development in particular; Increase in agricultural (vi) Institutional development and and industrial production; Tourism and development management; (vii) infrastructure development; Proper Tourism; (viii) Industrial management and utilization of natural development; (ix) Development of resources. backward class and region; (x) Sports and culture Sindhuli Mahottari Ramechhap 2000/01 – Sustainable social, Integrated development in (i) Physical infrastructure (road, 2,131,888 2006/07 economic and socio-economic aspects; Overall electricity, communication), sustainable development of district by mobilizing alternative energy, residence and town development (Able, local resources; Development of human development, industry, mining and Prosperous and resources and information system; tourism; (ii) Education, culture and Civilized Capacity enhancement of local bodies sports; (III) Drinking