Locale-Specific Sugar Packet Opening by Lesser Antillean Bullfinches In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product Catalog

LOG UCT CATA 2021 PROD Favorite Foods, Inc | Somersworth, NH Your local & family owned Foodservice Distributor Table of Contents Appetizers............................................................. Page 3 Baked Goods........................................................ Page 4 Batters & Doughs.................................................. Page 9 Beans.................................................................... Page 11 Beverages............................................................. Page 12 Breader & Stuffing................................................. Page 17 Cereal & Waffles................................................... Page 18 Chemicals............................................................. Page 19 Condiments & Sauces........................................... Page 22 Crackers & Snacks................................................ Page 29 Dairy...................................................................... Page 30 Extracts & Syrups.................................................. Page 49 Frostings & Fillings.................................................Page 42 Fruit....................................................................... Page 44 Meat...................................................................... Page 45 Mixes & Flour........................................................ Page 60 Muffins & Pastries................................................. Page 64 Non Foods............................................................ Page 66 Oil & Shortening................................................... -

Accents Stylish Details Accentuate the Tabletop

Accents Stylish Details Accentuate The Tabletop don.com | 800.777.4DON Accents: Details that are emphasized by contrasting with their surroundings. On the tabletop, the addition of a single item can make all the difference in the world. A stainless steel basket, a stunning bud vase, a truly unique set of salt & pepper shakers can add just the touch of style your tabletop needs to become the perfect stage for your culinary creations. Contents Ambiance ...............................24 – 27 Creamers..................................17, 18 Menus ..............................................7 Serving Boards..........................10, 11 Teapots ..........................................22 Baskets ......................................3 – 5 Decanters .......................................22 Menu Stands ....................................7 Serving Platters .........................8 – 11 Tongs .......................................13, 15 Beverage Servers ............................22 Dinnerware ..........3, 12, 16, 24, 28, 30 Mini Cookware ........................29 – 31 Serving Utensils ......................12 – 15 Vases .............................................26 Beverage Service ....................20 – 23 Display Boxes ...................................5 Mini Serving Dishes .................28 – 31 Sugar Caddies ................................18 Votives ...........................................25 Bowls .........................................5, 12 Flight Caddies .................................21 Pitchers ..........................................23 -

Prisoner Diabetes Handbook

Prisoner Diabetes Handbook A Guide to Managing Diabetes— for Prisoners, by Prisoners published by the southern poverty law center Why A Handbook for Prisoners With Diabetes? Diabetes is important. It is common, chronic, and can cause disabling complications. What you do for yourself to take care of your diabetes is the most important factor in your diabetes being well controlled. Very little diabetes education is provided in prisons. There are few organized programs for prisoners with diabetes. Experience has shown that others with diabetes are a good source of information about the disease. By cooperating and sharing, diabetics can help each other. A diabetes support group has been meeting at Great Meadow Correctional Facility in Comstock, New York since 1997. This group helps prisoners with diabetes to improve their diabetes management. People in the group learn from the experi- Diabetics at Comstock Prison would ences of other prisoners with diabetes. There is a lot of sup- be lost without the support group to port and good fellowship in help them learn about diabetes. the diabetes group. Sometimes the group chooses Jimmie Lee a project to do together. In the fall of 2003 we decided to write a handbook to share what we learned about diabetes self care in prison. This handbook is by prisoners, for prisoners. Our goal is to help you manage your diabetes better yourself. 3 FACTS ABOUT DIABETES Type 2 Diabetes The pancreas makes too little insulin and the insulin doesn’t Diabetes is not just one disease but several different diseases that work well. all cause the same basic problem: too much sugar in the blood. -

The World of Flying Cars, Hover Boards and Holographic 3-D Images

THE NEXT KID GENIUS Welcome to the world of flying cars, hover boards and holographic 3-D images. Science and technology have accelerated dramatically, and continues to grow and forge new paths in shaping and developing the world around us. We are at an age of scientific marvels, where nothing imagined is unattainable. The Next Genius is an original, scripted series that focuses on young and innovative children, hosted by a charismatic child genius about to embark on a journey to the future. The host will take the young viewers on a fun and exciting trip to some of the biggest and most prestigious science fairs and meet the best and brightest of the young science aficionados. We will talk to them about what sparked their ideas, how they went about creating their exhibitions, and what they hope to accomplish in the future. We also venture inside the “Kitchen Laboratories” of these young adventurers to learn fun and innovative ways to conduct scientific experiments and projects that we can teach the young viewers to do right at home, using objects found in most ordinary kitchens. This is a show that encourages children to learn, hypothesize and create. Each week will feature a different science fair and different young pioneer who will discuss and demonstrate the individual project he or she has been working on and also showcasing some simple, complementary science projects that viewers can re-create at home. Some of the top fair winners and the kitchen science experiments would include: Episode 1: Not A Good Day For Umbrellas Science Fair Project: How Weather Works - The power of the wind can even be strong enough to power large wind turbines to make electricity! In this experiment, find out how you can make your own instrument to measure the speed and power of the wind. -

Beverages & More

Beverages & more Coffee Item# Pack Size Description 366550 42/3 oz. High Altitude Papua Coffee New Guinea 366542 42/2.5 oz. Italian Dark Roast Coffee 366512 2/5 lb. 100% Colombian Regular Whole Bean 366507 42/2.5 oz. 100% Arabica Decaf 366505 42/2.5 oz. 100% Colombian with filters 366504 48/2 oz. 100% Arabica Decaf 366502 48/2.5 oz. 100% Arabica Regular 366560 12/1 lb. Cold Crew Coffee Filter Pack Espresso Item# Pack Size Description 360442 6/1000 gr. Espresso Whole Bean 360425 6/150 ct. Espresso Pod Decaf 360423 6/150 ct. Espresso Pod Regular 360419 32/250 gr. Espresso Ground Regular 360417 32/250 gr. Espresso Ground Decaf Water & Sparkling Beverage Item# Pack Size Description 365250 12/1 ltr. glass Ferrarelle Italian Sparkling Water 365260 15/16.9 oz. glass Ferrarelle Italian Sparkling Water 365270 24/11.2 oz. glass Ferrarelle Italian Sparkling Water 365265 15/16.9 oz. glass Natia Italian Still Water 365255 12/1 ltr. glass Natia Italian Still Water 365190 12/33.8 oz. San Pellegrino Carbonated Spring Water 365186 15/25.3 oz. San Pellegrino Carbonated Spring Water 365184 24/16.9 oz. plastic San Pellegrino Carbonated Spring Water 365180 24/16.9 oz. San Pellegrino Carbonated Spring Water 365175 24/8.45 oz. San Pellegrino Carbonated Spring Water 365206 12/33.8 oz. Panna Still Water 365350 24/16.9 oz. Panna Still Water 365229 4/6 pk. can Aranciata Rossa Sparkling Fruit Beverage 365217 4/6 pk. can Aranciata Sparkling Fruit Beverage 365215 4/6 pk. -

Survival Kits for Every Need

Survival Kits for Every Need Here is a variety of things you can add to a survival kit. Choose the items that seem appropriate to the moment, package in a pretty container, wrap with tissue and tie with ribbon. Add a card with the name of the survival kit and the meaning of the contents. SWEET & SOUR CANDY To help you appreciate the differences in others. A STICK OF GUM To remind you to stick with it To remind you to "chews" the right thing A CHOCOLATE KISS To remind you that someone loves you. A TOOTSIE ROLL To remind you not bite off more than you can chew. SMARTIES To remind you that you are smart. STARBURST To give you a burst of energy on the days you don't have any A PAPER CLIP To help keep things together when they seem to be getting out of control. PENCIL For the next time somebody says "get the lead out" (thanks Karen P.) BALLOON To remind you not to blow up (thanks Karen P.) A TISSUE To wipe away a tear-- your own or someone else's. A CANDY KISS To say "I love you" in a sweet way. ERASER To remind you that everyday you can start with a clean slate. A POEM To share the beauty of words. A PENNY So that you will never have to say, "I'm broke." A MARBLE In case someone says "You've lost all your marbles!" EYES (googly ones) To help you see the good in others (thanks Karen P.) PACKET OF SEEDS To remind you that you are always growing! CONFETTI To celebrate your joys of life. -

Rethink Your Drink

University of Hawai’i at Manoa, College of Tropical Agriculture & Human Resources, Department of Family & Consumer Sciences, Department of Human Nutrition, Food and Animal Science Cooperative Extension Service, Nutrition Education for Wellness www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/NEW Rethink Your Drink Choosing healthy beverages is a great first step to an overall healthy diet. Americans are drinking more soda and other sweetened beverages than ever. Many drinks now come in larger cups and cans, containing more than one 8-ounce serving. Drinking sweetened beverages may lead to weight gain, overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Eat your calories rather than drink your calories. How much fluid do you need? • Children: ~4 to 11 cups of fluids a day • Adults: ~9 to 13 cups of fluids a day • Amounts depend on age, gender, level of physical activity, altitude and climate. During hot weather, you will need more fluids, but don’t go by thirst alone. To prevent dehydration, drink plenty of water throughout the day, even before going outdoors. One way to tell if you are drinking enough fluids is to check the color of your urine. Your urine should be light yellow in color. If it is a dark color, you need to drink more water. Benefits of Drinking Water: Your Body’s Perfect Drink Drinking water is the best strategy to rethink your drink. Water is the perfect beverage— water is calorie-free, sugar-free, fat-free, and almost free (when it’s from the tap). Water is the best choice to stay hydrated before, during, and after physical activity. -

Recipe Carb List 11-22-19

Gladstone School District Page 1 Recipe Carbohydrates List Nov 22, 2019 Between 0 and 100 Grams Carbohydrates No. Description Portion Size (Grams) BREAD 500305 AZTEC GRAIN SALAD 1 CUP 53.56 000347 BAGELS,PLAIN,ENRICHED 1 EACH 37.19 500010 BAKING POWDER BISCUITS 1 EACH 22.09 500011 BANANA BREAD SQUARES SERVING 25.56 001086 BISCUITS: PLAIN PURCH (2oz) EACH 18.85 000355 BISCUITS: PLAIN,PURCH (2.5") EACH 18.85 500037 BREAD STUFFING SERVINGS 22.64 500040 BROWN BREAD EACH 19.27 000117 Brown Rice .5 cup 33.00 500027 BROWN RICE PILAF 1/2 CUP 30.36 500088 CORNBREAD SERVINGS 18.03 000121 Cornbread 2oz 26.58 500089 CORNBREAD STUFFING SERVINGS 21.19 000232 CRACKERS 4 EACH 8.89 000233 CRACKERS,GRAHAM 4 EACH 44.03 000353 ENGLISH MUFFINS,PLAIN,TOASTED 1/2 EACH 13.69 500099 FRIED RICE 3/4 CUP 29.37 000169 Fritos 2oz 40.00 500111 ITALIAN BREAD EACH 28.23 500119 MASTER MIX 1/2 CUP 40.68 500325 MEDITERRANEAN QUINOA SALAD 3/4 CUP 22.66 500125 MUFFIN SQUARES SERVINGS 16.87 500133 OATMEAL MUFFIN SQUARES SERVINGS 34.51 500303 OODLES OF NOODLES CUP 43.45 500137 ORANGE RICE PILAF 1/2 CUP 27.85 500141 PANCAKES EACH 16.26 500327 PEPPY QUINOA 1/2 CUP 28.60 500147 PIZZA CRUST SERVINGS 26.11 500155 POURABLE PIZZA CRUST SERVINGS 26.02 500163 RICE-VEGETABLE CASSEROLE 2/3 CUP 19.62 500164 ROLLS (YEAST) EACH 29.80 500173 SPANISH RICE 1/3 CUP 13.69 000237 Stuffing 1/4 cup 35.44 500181 SWEET POTATO- PLUM BREAD SQUAR SERVING 46.48 000326 TOAST, MIXED GRAIN BREAD SLICE 11.35 000324 TOAST, WHITE BREAD SLICE 12.03 000367 TOAST,RAISIN 1 SLICE 13.66 000325 TOAST,WHOLE-WHEAT BREAD -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0227686 A1 Saghbini Et Al

US 20140227686A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0227686 A1 Saghbini et al. (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 14, 2014 (54) STABILIZED CHEMICAL DEHYDRATION OF Publication Classification BOLOGICAL MATERAL (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: GENTEGRALLC, Pleasanton, CA CI2O I/68 (2006.01) (US) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC .................................... CI2O I/6806 (2013.01) (72) Inventors: Michael Saghbini, Poway, CA (US); USPC ........................................................... 435/6.1 Michael Hogan, Tucson, AZ (US); Chunnian Shi, San Diego, CA (US); (57) ABSTRACT Brian Dalby, Carlsbad, CA (US); David Wong, San Marcos, CA (US) The present invention provides compositions and methods that enable the stabilization and storage of samples by con (73) Assignee: GENTEGRALLC, Pleasanton, CA tacting a sample with an assembly of particles, and reducing (US) the water activity level of the contacted sample. By reducing the water activity level of the sample, the assembly of par (21) Appl. No.: 14/254,478 ticles minimizes the degradation of the sample. Stabilizers may or may not be added to the assembly of particles to (22) Filed: Apr. 16, 2014 further minimize the degradation of the sample. Subsequently to storage in the assembly of particles, the samples are recov Related U.S. Application Data erable by eluting the assembly of particles with a fluid solu tion. In one embodiment, the entire assembly of particles will (63) y apps No. 13/081,436, filed on dissolve into the solution. In another embodiment, only part pr. o. s of the assembly of particles will dissolve into the solution. (60) Provisional application No. 61/321,269, filed on Apr. -

Grand Total Awards 2,200,000.00

Gail Sharry, Executive Director NHPS Food Service P: (475) 220-1610 F: (203) 946-7650 To: New Haven Board of Education Finance and Operations Committee From: Thomas Lamb, Chief Operating Officer Gail Sharry, Executive Director Michael Gormany, City Budget Director Date: May 28, 2021 Re: Award of Contract for NHPS Food Service for Grocery Items Purchases for fiscal year 2021-22 Executive Summary: Approval is requested for an award of contract(s) under RFP# 2021-04-1371 for the purchase of Grocery items for fiscal year 2021-22 for NHPS Food Service. Minority Renewal or Award of or Contract/Agreement City Award Vendor Women Vendor Vendor Name City, State, Zip Amount not Address Owned Number to Exceed Small Business? Thurston Wallingford, CT Award 43356 30 Thurston Dr $1,800,000 Foods, Inc 06492 Nardone Bros 420 New Hanover Twp, PA Award 50643 $150,000 Baking Co Inc. Commerce Blvd 18706 Gilman Cheese 300 S. Riverside Award TBD Gilman, WI 54433 $100,000 Corporation Drive Chinese Food 5600 Elmhurst Oviedo. FL Award 52652 $100,000 Solutions, Inc Cir. 32765 2601 Blake Award TBD Ripple Denver, CO 80205 $50,000 Street Suite 300 Grand Total 2,200,000.00 Awards Contract or Agreement #: TBD Funding Source & Account #: 25215200-55587 Key Questions: (Please have someone ready to discuss the details of each question during the Finance & Operations meeting or this proposal might not be advanced for consideration by the full Board of Education): Central Kitchen | 75 Barnes Avenue, New Haven, CT 06513 http://www.nhpscnp.org/ Excellence in Education. Gail Sharry, Executive Director NHPS Food Service P: (475) 220-1610 F: (203) 946-7650 1. -

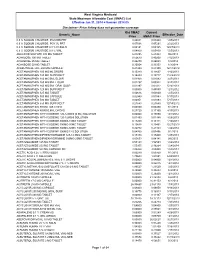

Price Listing Does Not Guarantee Coverage West Virgini

West Virginia Medicaid State Maximum Allowable Cost (SMAC) List Effective Jan 31, 2014 ‑ Version 2014.05 Disclaimer: Price listing does not guarantee coverage Old SMAC Current Generic_Name Effective_Date Price SMAC Price 0.9 % SODIUM CHLORIDE PGGYBK PRT 0.04001 0.03440 1/25/2013 0.9 % SODIUM CHLORIDE PGY VL PRT 0.07096 0.07291 2/22/2013 0.9 % SODIUM CHLORIDE 0.9 % IV SOLN 0.00141 0.00165 12/27/2013 0.9 % SODIUM CHLORIDE 0.9 % VIAL 0.04800 0.05830 1/25/2013 ABACAVIR SULFATE 300 MG TABLET 6.27295 6.21453 9/6/2013 ACARBOSE 100 MG TABLET 0.50679 0.40200 7/12/2013 ACARBOSE 25 MG TABLET 0.46270 0.26023 1/3/2014 ACARBOSE 50 MG TABLET 0.35054 0.33353 1/3/2014 ACEBUTOLOL HCL 200 MG CAPSULE 0.21353 0.21350 12/14/2012 ACETAMINOPHEN 100 MG/ML DROPS 0.15340 0.11667 4/12/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 120 MG SUPP.RECT 0.16289 0.19717 11/22/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 160 MG/5ML ELIXIR 0.01968 0.01083 9/27/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 160 MG/5ML LIQUID 0.01297 0.00932 9/27/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 160 MG/5ML ORAL SUSP 0.02397 0.02412 5/24/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 325 MG SUPP.RECT 0.00000 0.45850 12/1/2012 ACETAMINOPHEN 325 MG TABLET 0.00616 0.00830 1/25/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 500 MG CAPSULE 0.02940 0.01093 5/17/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 500 MG TABLET 0.00951 0.01093 5/17/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 650 MG SUPP.RECT 0.21683 0.21680 12/14/2012 ACETAMINOPHEN 80 MG TAB CHEW 0.04850 0.04450 3/1/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN 80MG/0.8ML DROPS 0.27720 0.17160 4/19/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN WITH CODEINE 120-12MG/5 (5 ML) SOLUTION 0.00000 0.15890 12/1/2012 ACETAMINOPHEN WITH CODEINE 120-12MG/5 SOLUTION 0.01490 0.01485 4/26/2013 ACETAMINOPHEN -

Materials Week 7 Display Board Juice Drink Hi-C Flashin Fruit

Juice Board – Week 7 Activity Description What Has More Sugar? Materials Week 7 display board Juice Drink Hi-C Flashin Fruit Punch – juice drink juice box 6.75 fl.oz 24 grams of sugar 6 sugar packets – 6 teaspoons of sugar Soda Coca-Cola 90 calories per can 7.5 fl.oz 25 grams of sugar 6 sugar packets –6 teaspoons of sugar 100% Juice Juicy Juice or Mott’s 100% juice box 6.75 fl oz 24 grams of sugar 6 sugar packets – 6 teaspoons of sugar Domino sugar packets –18 are needed for activity; pack at least 30 so there are more than are needed for distribution Reinforcers – Sugar scrub Basket/container for reinforcers Raffle box Raffle slips Parent handouts Evaluation form Table for supporting board (folding table) Raffle prize to give away for current week – Fruit basket (mangos, oranges, apples) Raffle prize for following week – Set of Pyrex measuring cups – FOR DISPLAY ONLY Raffle prize winner’s name Target Audience Parents of Pre – School Children Table/Board Set Up Place board on folding table Place raffle box, pens/pencils, and raffle slips on table Place parent handouts on table Place all activity materials on table Place raffle prize and raffle winner’s name on table Place raffle prize for following week on table (If there is space) Activity: Parent will learn that 100% juice, juice drinks, and soda all contain the same amount of sugar. 1. The student will set the four beverages on the table and have several sugar packets available. 2. The student will greet the parent and ask him/her if they want to enter their name in the weekly raffle or receive a giveaway.