Sexual Animals”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If You're Not That As an Asian Woman, You're Not Shit As an Asian

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2016 “If you’re not that as an Asian woman, you’re not shit as an Asian woman.”: (re)negotiating racial and gender identities Andi T. Remoquillo DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Remoquillo, Andi T., "“If you’re not that as an Asian woman, you’re not shit as an Asian woman.”: (re)negotiating racial and gender identities" (2016). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 221. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/221 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “If You’re Not That as an Asian Woman, You’re Not Shit as an Asian Woman.” (Re)negotiating Racial and Gender Identities Andi T. Remoquillo M.A. Thesis CMS Citations Committee Chair: Sanjukta Mukherjee Second Reader: Robin Mitchell Third Reader: Ada Cheng June 2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments (4) Introduction (5) I. 1.1 Framing the project II. 1.2 Situating Myself in the Project III. 1. Literature Review IV. 1.3 Methodology V. 1.4 Summary of Chapters Chapter One: Establishing Asian Women as the Hypersexual Other Within U.S. Immigration Laws (35) 1.1 1924 National Origins Formula 1.2 War Brides Act of 1945 1.3 Immigration Act of 1952 1.4 Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 1.5 1986 Immigration and Reform Act Chapter Two: The Hypersexualization of Asian/Asian-American Women in Western Medias (57) 2.1 The Dragon Lady and the Lotus Flower: Terry and the Pirates to Yellowface Porn in Stag Film (1920s) 2.2 Asian-American women in U.S. -

NECROPHILIC and NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page

Running head: NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page: Florida Gulf Coast University Thesis APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Christina Molinari Approved: August 2005 Dr. David Thomas Committee Chair / Advisor Dr. Shawn Keller Committee Member The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 1 Necrophilic and Necrophagic Serial Killers: Understanding Their Motivations through Case Study Analysis Christina Molinari Florida Gulf Coast University NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Literature Review............................................................................................................................ 7 Serial Killing ............................................................................................................................... 7 Characteristics of sexual serial killers ..................................................................................... 8 Paraphilia ................................................................................................................................... 12 Cultural and Historical Perspectives -

Chinese International Students Negotiating Dating in Sydney

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Sojourner intimacies: Chinese international students negotiating dating in Sydney Xi Chen SID 440567851 A treatise submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Gender and Cultural Studies The University of Sydney June 2018 This thesis has not been submitted for examination at this or any other university. 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all the participants who volunteered to contribute their lived experiences. Most of my interviews started with coffee and shy smiles; many ended with a handshake or a long hug, others ended in quiet tears or heart-wrenching silence… Your struggles calcified into the weight of this thesis, and I am forever indebted to your unreserved candidness and generosity. I would also like to thank my mother – an intelligent, loving, and incredibly tough single mother: “You are my personal Wonder Woman.” None of my reality today would exist, had you not unconditionally supported my ambitions, my choice of major, or my three-year-old unconventional open relationship with my partner. Finally, I would like to thank the members of the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies for their kind support and friendship. A very special thank-you goes to Dr Astrida Neimanis and my direct supervisor Dr Jessica Kean. Your intellectual generosity opened my eyes to a new horizon, and perhaps more importantly, your patience and care have, again and again, forged my doubts into conviction. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Trans/National Chinese Bodies Performing Sex, Health, and Beauty in Cinema and Media a Diss

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Trans/national Chinese Bodies Performing Sex, Health, and Beauty in Cinema and Media A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Mila Zuo 2015 © Copyright by Mila Zuo 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Trans/national Chinese Bodies Performing Sex, Health, and Beauty in Cinema and Media by Mila Zuo Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Kathleen A. McHugh, Chair This dissertation explores the connections between Chinese body cultures and transnational screen cultures by tracing the Chinese body through representation in contemporary cinema and media in the post-Mao era. Images of Chinese bodies participate in the audio-visual manufacture of desire and pleasure, and ideas of “Chinese- ness” endure through repetitive, mediated performance. This dissertation examines how representations of sex, health, and beauty are mediated by social, cultural, and political belief systems, and how cine/televisual depictions of the body also, in turn, mediate gender, cultural, racial and ethnic identifications within and across national boundaries. The bodily practices and behaviors in the quotidian arenas of sex, health, and beauty reflect the internalization of culture and the politics of identity construction. This dissertation is interested in how the pleasures of cinema relate to the politics of the body, ii and how the pleasures of the body relate to the politics of cinema. -

R Chou Dissertation

ASIAN AMERICAN SEXUAL POLITICS: THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY A Dissertation by ROSALIND SUE CHOU Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 Major Subject: Sociology ASIAN AMERICAN SEXUAL POLITICS: THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY A Dissertation by ROSALIND SUE CHOU Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joe R. Feagin Committee Members, Wendy Leo Moore William A. McIntosh Marian Eide Head of Department, Mark Fossett May 2010 Major Subject: Sociology iii ABSTRACT Asian American Sexual Politics: The Construction of Race, Gender, and Sexuality. (May 2010) Rosalind Sue Chou, B.S., Florida State University; M.S., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joe R. Feagin Why study Asian American sexual politics? There is a major lack of critical analysis of Asian Americans and their issues surrounding their place in the United States as racialized, gendered, and sexualized bodies. There are three key elements to my methodological approach for this project: standpoint epistemology, extended case method, and narrative analysis. In my research, fifty-five Asian American respondents detail how Asian American masculinity and femininity are constructed and how they operate in a racial hierarchy. These accounts will explicitly illuminate the gendered and sexualized racism faced by Asian Americans. The male respondents share experiences that highlight how “racial castration” occurs in the socialization of Asian American men. -

Rewriting Images of the Asian Fetish

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2005-6: Word Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate & Image Research Fellows 4-1-2006 Made in the USA: Rewriting Images of the Asian Fetish Maggie Chang University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2006 Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Chang, Maggie, "Made in the USA: Rewriting Images of the Asian Fetish" (2006). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2005-6: Word & Image. 6. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2006/6 2005-2006 Penn Humanities Forum on Word & Image, Undergraduate Mellon Research Fellows. URL: http://humanities.sas.upenn.edu/05-06/mellon_uhf.shtml This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2006/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Made in the USA: Rewriting Images of the Asian Fetish Abstract "My voice reveals the hidden power hidden within." A woman of Asian descent appears to be an entertainer, possibly a courtesan or geisha, wearing a pseudo-Chinese dress and hairdo; her hands are curled in front of her in an "Oriental-like" gesture as if she is dancing, and her head is tilted coyly with a cryptic smile (Figure 1). She gives a sexually suggestive expression and gaze but hesitates to speak. Another version with the same woman reads, "In silence I see. With WISDOM, I speak." These advertisements make up one part of the "Find Your Voice" Virginia Slims campaign. The campaign consisted of four different ads, each featuring women of distinctive races with stereotyping text. Disciplines Other Arts and Humanities Comments 2005-2006 Penn Humanities Forum on Word & Image, Undergraduate Mellon Research Fellows. -

Controversy Trend Detection in Social Media Rajshekhar Vishwanath Chimmalgi Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2013 Controversy trend detection in social media Rajshekhar Vishwanath Chimmalgi Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Engineering Science and Materials Commons Recommended Citation Chimmalgi, Rajshekhar Vishwanath, "Controversy trend detection in social media" (2013). LSU Master's Theses. 2000. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2000 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTROVERSY TREND DETECTION IN SOCIAL MEDIA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Interdepartmental Program in Engineering Science by Rajshekhar V. Chimmalgi B.S., Southern University, 2010 May 2013 To my parents Shobha and Vishwanath Chimmalgi. ii Acknowledgments Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Dr. Gerald M. Knapp for his patience, guidance, encouragement, and support. I am grateful for having him as an advisor and having faith in me. I would also like to thank Dr. Andrea Houston and Dr. Jianhua Chen for serving as members of my committee. I would like to thank Dr. Saleem Hasan, for his guidance and encouragement, for pushing me to pursue graduate degree in Engineering Science under Dr. -

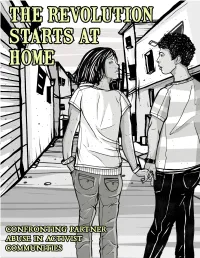

Confronting Partner Abuse in Activist Communities

Confronting Partner Abuse in Activist Communities 1 The Revolution Starts at Home I am not proposing that sexual violence and domestic violence will no longer ex- ist. I am proposing that we create a world where so many people are walking around with the skills and knowledge to support someone that there is no longer a need for anonymous hotlines. I am proposing that we break through the shame of survivors (a result of rape cul- ture) and the victim-blaming ideology of all of us (also a result of rape culture), so that survivors can gain support from the people already in their lives. I am propos- ing that we create a society where com- munity members care enough to hold an abuser accountable so that a survivor does not have to flee their home. I am proposing that all of the folks that have been disap- pointed by systems work together to create alternative systems. I am proposing that we organize. Rebecca Farr, CARA member 2 Confronting Partner Abuse in Activist Communities contents Where the revolution started: an introduction 5 Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha Introduction 9 Ching-In Chen The revolution starts at home: pushing through the fear 10 Jai Dulani There is another way 15 Ana Lara How I learned to stop worrying and love the wreckage 21 Gina de Vries Infestation 24 Jill Aguado, Anida Ali, Kay Barrett, Sarwat Rumi, of Mango Tribe No title 30 Anonymous I married a marxist monster 33 Ziggy Ponting Philly’s pissed and beyond 38 Timothy Colman Notes on partner consent 44 Bran Fenner Femora and fury: on IPV and disability 48 Peggy -

Download This PDF File

GRIFFITH JOURNAL OF LAW & HUMAN DIGNITY Editor-in-Chief Michelle Gunawan Special Issue Executive Editors Deputy Editor Isaac Avery Alexandria Neumann Josephine Vernon Editors Vanessa Antal Kim Johnson Myles Bayliss Leanne Mahly Mark Batakin Juliette Murray Reyna de Bellerose Yassamin Ols n Renee Curtis Isabelle Quinn Elizabeth Englezos o Danyon Jacobs Andrea Rimovetz Consulting Executive Editor Dr Allan Ardill Gender, Culture, and Narrative Special Issue 2017 Published in April 2017, Gold Coast, Australia by the Griffith Journal of Law & Human Dignity ISSN: 2203-3114 We acknowledge and thank Indie Grant Male for creating our Special Issue cover art - and Molly Jackson . We also extend our appreciation to Molly Jackson for her indispensable role in shaping the vision and content of the Special Issue in its early stages. CONTENTS MICHELLE GUNAWAN EDITORIAL 1 6 DR KATHERINE FALLAH RE GEORGIO: AN INTIMATE ACCOUNT OF TRANSGENDER INTERACTIONS WITH LAW AND SOCIETY 40 PIDGEON PAGONIS FIRST DO NO HARM: HOW INTERSEX KIDS ARE HURT BY THOSE WHO HAVE TAKEN THE HIPPOCRATIC OATH 52 DR CARMEN LAWRENCE WOMEN, SEXISM, AND POLITICS: DOES PSYCHOLOGY HELP? RACHEL KUO SCRIPTING RACED AND GENDERED MYTHS OF 68 (UN)BELONGING 91 TUANH NGUYEN AND GENDER, CULTURE, AND THE LEGAL PROFESSION: A REYNAH TANG TRAFFIC JAM AT THE INTERSECTION DR LAUREN ROSEWARNE FROM MEMOIR TO MAKE BELIEVE: BEYONCÉ’S 112 LEMONADE AND THE FABRICATION POSSIBILITY ELISE STEPHENSON, CLIMBING THE ‘STAIRCASE’: DO EEO POLICIES 122 KAYE BROADBENT, AND CONTRIBUTE TO WOMEN ACHIEVING SENIOR GLENDA -

HOOKED on RACE: an Investigation of the Racialized Hookup Experiences of White, Asian, and Black College Women

HOOKED ON RACE: An Investigation of the Racialized Hookup Experiences of White, Asian, and Black College Women A Thesis Presented to the Department of Sociology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors By Nicole Chen University of Michigan April 2014 Professor Karin Martin, Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies in Sociology Honors Faculty Professor Professor Karyn Lacy, Associate Professor of Sociology Honors Faculty Advisor ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Karin Thank you for your never-ending support during the past year and a half. I would have been completely lost without your guidance and my thesis experience would not have been so positive were it not for you. To Professor Lacy Thank you for your expertise and for taking the time to serve as my mentor. Your kind words always gave me the encouragement I needed, and it was an absolute pleasure working with you. To my friends Thank you for putting up with me as I complained about transcribing/coding/my thesis in general. Especially Michael, who empathized with me all the way. To the guy who told me “You’re the first Asian girl I’ve ever hooked up with” Thank you for causing me to question the relationship between race and sexuality, and thus inspiring me to write this piece of work. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………………. 4 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………... 5 LITERATURE REVIEW………………………………………………………………... 6 METHODOLOGY……………………………………………………………………….. 14 RESULTS AND ANALYSIS…………………………………………………………….. 20 I. Hookup Experience Demographics……………………………………… 20 II. Participation in Hookup Culture………………………………………... 22 III. Choosing a Hookup Partner……………………………………………... 28 IV. Reasons For and Against Engaging in an Interracial Hookup………… 40 V. -

Fat Sexuality and Its Representations in Pornographic Imagery

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School June 2019 "Roll" Models: Fat Sexuality and Its Representations in Pornographic Imagery Leah Marie Turner University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Women's Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Turner, Leah Marie, ""Roll" Models: Fat Sexuality and Its Representations in Pornographic Imagery" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7976 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Roll” Models: Fat Sexuality and Its Representations in Pornographic Imagery by Leah Marie Turner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Diane Price-Herndl, Ph.D. Kimberly Golombisky, Ph.D. David Rubin, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 28, 2019 Keywords: Namio Harukawa, Ashley Graham, fatness, sex, feminism, women Copyright © 2019, Leah Marie Turner Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. ii Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... -

Neither Victim Nor Fetish – ‘Asian’ Women and the Effects of Racialization in the Swedish Context

Linköping university - Department of Social and Welfare Studies (ISV) Master´s Thesis, 30 Credits – MA in Ethnic and Migration Studies (EMS) ISRN: LiU-ISV/EMS-A--19/01--SE Neither victim nor fetish – ‘Asian’ women and the effects of racialization in the Swedish context Mavis Hooi Supervisor: Professor Stefan Jonsson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DEDICATION I wish to express my gratitude to the people who have made this work possible. To the women who opened their hearts and shared their experiences with me: thank you, it has been a privilege to listen to and be entrusted to present your stories. To professor Stefan Jonsson and all the teachers at REMESO whose support and encouragement these past two years should not be underestimated; whose commitment and efforts towards shaping a better world for all inspires hope for the future: thank you. To my friends and family who have imparted heartfelt well-wishes and kind words of confidence along the way—Alex, Dylan, Raha, Rudeina, Carola, Charlotte, and many more: thank you. And to Fredrik, whose love and tireless support has enabled me to pursue this path; whose energy, enthusiasm and endless optimism throughout has been heartening— you’re my rock: thank you. This work is dedicated to my fellow people of colour, especially my ‘Asian’ sisters, who are on the same path of learning how to free our minds. Mavis Hooi Linköping, 21 December 2018 ABSTRACT Title: Neither victim nor fetish – ‘Asian’ women and the effects of racialization in the Swedish context Author: Mavis Hooi Year: 2018 People who are racialized in Sweden as ‘Asian’—a panethnic category—come from different countries or ethnic backgrounds and yet, often face similar, gender-specific forms of discrimination which have a significant impact on their whole lives.