R Chou Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Aoki Memorial Committee the Life and Times of Richard Aoki

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF RICHARD ords Richard Aoki Memorial Committee The Life and Times of Richard Aoki in his own words From Richard Aoki's interview with KPFA Apex Reporter, Wayie Ly Taped July 2006 Published by the Richard Aoki Memorial Committee © May 2009 2066 University Avenue Berkeley California 94704 [email protected] www.ramemorial.blogspot.com 1 their empire in the Far East. If one steps back and looks at a map of the Pacific, one can see that those two countries were on a collision course for When Elephants Fight, the Grass Suffers conflict. I'm Japanese American. I'm a third generation born citizen of this country. Now in 1941 when the war occurred, it became bad news for people of My grandparents, both maternal and paternal, were immigrants from Japan Japanese and Japanese American ancestry here in the US. There's an to the United States at the turn of the century. African proverb that goes like this, "when the elephants fight, the grass Both my parents were born here in this country and were American citizens suffers." The Japanese here were the grass in that case. A hundred and by birth. This may not seem like a big deal at this moment, but it becomes an twenty thousand Japanese and Japanese Americans were interned in ten interesting fact as we go further into the history of the Japanese in the concentration camps, euphemized as "relocation centers," during the period United States. of the war. My family was not an exception. My parents, grandparents and myself ended up in a concentration camp. -

On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities In

“Go eat a bat, Chang!”: On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19 Fatemeh Tahmasbi Leonard Schild Chen Ling Binghamton University CISPA Boston University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn Gianluca Stringhini Yang Zhang Binghamton University Boston University CISPA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Savvas Zannettou Max Planck Institute for Informatics [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives in COVID-19, Sinophobia, Hate Speech, Twitter, 4chan unprecedented ways. In the face of the projected catastrophic conse- ACM Reference Format: quences, most countries have enacted social distancing measures in Fatemeh Tahmasbi, Leonard Schild, Chen Ling, Jeremy Blackburn, Gianluca an attempt to limit the spread of the virus. Under these conditions, Stringhini, Yang Zhang, and Savvas Zannettou. 2021. “Go eat a bat, Chang!”: the Web has become an indispensable medium for information ac- On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the quisition, communication, and entertainment. At the same time, Face of COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (WWW ’21), unfortunately, the Web is being exploited for the dissemination April 19–23, 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages. of potentially harmful and disturbing content, such as the spread https://doi.org/10.1145/3442381.3450024 of conspiracy theories and hateful speech towards specific ethnic groups, in particular towards Chinese people and people of Asian 1 INTRODUCTION descent since COVID-19 is believed to have originated from China. -

If You're Not That As an Asian Woman, You're Not Shit As an Asian

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2016 “If you’re not that as an Asian woman, you’re not shit as an Asian woman.”: (re)negotiating racial and gender identities Andi T. Remoquillo DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Remoquillo, Andi T., "“If you’re not that as an Asian woman, you’re not shit as an Asian woman.”: (re)negotiating racial and gender identities" (2016). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 221. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/221 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “If You’re Not That as an Asian Woman, You’re Not Shit as an Asian Woman.” (Re)negotiating Racial and Gender Identities Andi T. Remoquillo M.A. Thesis CMS Citations Committee Chair: Sanjukta Mukherjee Second Reader: Robin Mitchell Third Reader: Ada Cheng June 2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments (4) Introduction (5) I. 1.1 Framing the project II. 1.2 Situating Myself in the Project III. 1. Literature Review IV. 1.3 Methodology V. 1.4 Summary of Chapters Chapter One: Establishing Asian Women as the Hypersexual Other Within U.S. Immigration Laws (35) 1.1 1924 National Origins Formula 1.2 War Brides Act of 1945 1.3 Immigration Act of 1952 1.4 Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 1.5 1986 Immigration and Reform Act Chapter Two: The Hypersexualization of Asian/Asian-American Women in Western Medias (57) 2.1 The Dragon Lady and the Lotus Flower: Terry and the Pirates to Yellowface Porn in Stag Film (1920s) 2.2 Asian-American women in U.S. -

NECROPHILIC and NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page

Running head: NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page: Florida Gulf Coast University Thesis APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Christina Molinari Approved: August 2005 Dr. David Thomas Committee Chair / Advisor Dr. Shawn Keller Committee Member The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 1 Necrophilic and Necrophagic Serial Killers: Understanding Their Motivations through Case Study Analysis Christina Molinari Florida Gulf Coast University NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Literature Review............................................................................................................................ 7 Serial Killing ............................................................................................................................... 7 Characteristics of sexual serial killers ..................................................................................... 8 Paraphilia ................................................................................................................................... 12 Cultural and Historical Perspectives -

The Effect of Acculturative in the Psychological Adjustment Of

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 The ffecE t of Acculturative in the Psychological Adjustment of Immigrant Hispanic Parents Estela Garcia Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Estela Garcia has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Nina Nabors, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. Susana Verdinelli, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. Tracy Mallett, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2016 Abstract The Role of Acculturative Stress in the Psychological Adjustment of Immigrant Hispanic Parents by Estela Garcia MS, City College of The City University Of New York, 1995 BA, The City College of The City University of New York, 1990 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clinical Psychology Walden University December of 2016 Abstract Hispanic immigrant parents are a growing yet understudied population. Few studies have addressed the relationship between Hispanic immigrant parents and the acculturation process. The purpose of this study was to determine how acculturative stress, racism, language proficiency, poor coping style, and low levels of social support affect the psychological adjustment of Hispanic immigrant parents. -

Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 1 - - 2 - Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea The Representation of Black Heroism in American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 4 - Table of Contents: Preface Chapter One: The Western Victimization of African Americans during and after Slavery 1.1 – Visual Culture in Propaganda 1.2 - African Americans as Victims of the System of Slavery 1.3 - The Gift of Freedom 1.4 - The Influence of White Stereotypes on the Perception of Blacks 1.5 - Racial Discrimination in Criminal Justice 1.6 - Conclusion Chapter Two: Black Heroism in Modern American Cinema 2.1 – Representing Racial Agency Through Passive Characters 2.2 - Django Unchained: The Frontier Hero in Black Cinema 2.3 - Character Development in Django Unchained 2.4 - The White Savior Narrative in Hollywood's Cinema 2.5 - The Depiction of Black Agency in Hollywood's Cinema 2.6 - Conclusion Chapter Three: The Different Interpretations -

Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Jewish Studies 2020 Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs Part of the History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fordham University, "Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate" (2020). Faculty Publications. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jewish Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Media Technology & The Dissemination of Hate November 15th, 2019-May 31st 2020 O’Hare Special Collections Fordham University & Center for Jewish Studies Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Highlights from the Fordham Collection November 15th, 2019-May 31st, 2020 Curated by Sally Brander FCRH ‘20 Clare McCabe FCRH ‘20 Magda Teter, The Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies with contributions from Students from the class HIST 4308 Antisemitism in the Fall of 2018 and 2019 O’Hare Special Collections Walsh Family Library, Fordham University Table of Contents Preface i Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate 1 Christian (Mis)Interpretation and (Mis)Representation of Judaism 5 The Printing Press and The Cautionary Tale of One Image 13 New Technology and New Opportunities 22 -

Chinese International Students Negotiating Dating in Sydney

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Sojourner intimacies: Chinese international students negotiating dating in Sydney Xi Chen SID 440567851 A treatise submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Gender and Cultural Studies The University of Sydney June 2018 This thesis has not been submitted for examination at this or any other university. 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all the participants who volunteered to contribute their lived experiences. Most of my interviews started with coffee and shy smiles; many ended with a handshake or a long hug, others ended in quiet tears or heart-wrenching silence… Your struggles calcified into the weight of this thesis, and I am forever indebted to your unreserved candidness and generosity. I would also like to thank my mother – an intelligent, loving, and incredibly tough single mother: “You are my personal Wonder Woman.” None of my reality today would exist, had you not unconditionally supported my ambitions, my choice of major, or my three-year-old unconventional open relationship with my partner. Finally, I would like to thank the members of the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies for their kind support and friendship. A very special thank-you goes to Dr Astrida Neimanis and my direct supervisor Dr Jessica Kean. Your intellectual generosity opened my eyes to a new horizon, and perhaps more importantly, your patience and care have, again and again, forged my doubts into conviction. -

Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary the Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation Would Like to Honour And

Lan- guage De- Coded Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary The Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation would like to honour and acknowledgeTreaty aknoledgment all that reside on the traditional Treaty 7 territory of the Blackfoot confederacy. This includes the Siksika, Kainai, Piikani as well as the Stoney Nakoda and Tsuut’ina nations. We further acknowledge that we are also home to many Métis communities and Region 3 of the Métis Nation. We conclude with honoring the city of Calgary’s Indigenous roots, traditionally known as “Moh’Kinsstis”. i Contents Introduction - The purpose Themes - Stigmatizing and power of language. terminology, gender inclusive 01 02 pronouns, person first language, correct terminology. -ISMS Ableism - discrimination in 03 03 favour of able-bodied people. Ageism - discrimination on Heterosexism - discrimination the basis of a person’s age. in favour of opposite-sex 06 08 sexuality and relationships. Racism - discrimination directed Classism - discrimination against against someone of a different or in favour of people belonging 10 race based on the belief that 14 to a particular social class. one’s own race is superior. Sexism - discrimination Acknowledgements 14 on the basis of sex. 17 ii Language is one of the most powerful tools that keeps us connected with one another. iii Introduction The words that we use open up a world of possibility and opportunity, one that allows us to express, share, and educate. Like many other things, language evolves over time, but sometimes this fluidity can also lead to miscommunication. This project was started by a group of diverse individuals that share a passion for inclusion and justice. -

Transnational Identity and Second-Generation Black

THE DARKER THE FLESH, THE DEEPER THE ROOTS: TRANSNATIONAL IDENTITY AND SECOND-GENERATION BLACK IMMIGRANTS OF CONTINENTAL AFRICAN DESCENT A Dissertation by JEFFREY F. OPALEYE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Joe R. Feagin Committee Members, Jane A. Sell Mary Campbell Srividya Ramasubramanian Head of Department, Jane A. Sell August 2020 Major Subject: Sociology Copyright 2020 Jeffrey F. Opaleye ABSTRACT Since the inception of the Immigration Act of 1965, Black immigrant groups have formed a historic, yet complex segment of the United States population. While previous research has primarily focused on the second generation of Black immigrants from the Caribbean, there is a lack of research that remains undiscovered on America’s fastest-growing Black immigrant group, African immigrants. This dissertation explores the transnational identity of second-generation Black immigrants of continental African descent in the United States. Using a transnational perspective, I argue that the lives of second-generation African immigrants are shaped by multi-layered relationships that seek to maintain multiple ties between their homeland and their parent’s homeland of Africa. This transnational perspective brings attention to the struggles of second-generation African immigrants. They are replicating their parents’ ethnic identities, maintaining transnational connections, and enduring regular interactions with other racial and ethnic groups while adapting to mainstream America. As a result, these experiences cannot be explained by traditional and contemporary assimilation frameworks because of their prescriptive, elite, white dominance framing and methods that were designed to explain the experiences of European immigrants. -

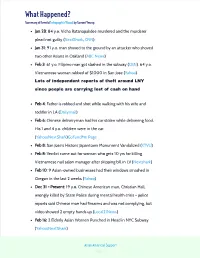

A Timeline of What Has Happened Since

What Happened? Summary of Events/Infographic Visual by Sammi Yeung Jan 28 : 84 y.o. Vicha Ratanapakdee murdered and the murderer plead not guilty (NextShark , CNN ) Jan 31 : 91 y.o. man shoved to the ground by an attacker who shoved two other Asians in Oakland (ABC News ) Feb 3 : 61 y.o. Filipino man got slashed in the subway (CBN). 64 y.o. Vietnamese woman robbed of $1000 in San Jose (Yahoo ) Lots of independent reports of theft around LNY since people are carrying lost of cash on hand Feb 4 : Father is robbed and shot while walking with his wife and toddler in LA (Dailymail ) Feb 6 : Chinese deliveryman had his car stolen while delivering food. His 1 and 4 y.o. children were in the car. ()Yahoo/NextShark GoFundMe Page Feb 8 : San Jose's Historic Japantown Monument Vandalized (KTVU ) Feb 8 : Verdict came out for woman who gets 10 yrs for killing Vietnamese nail salon manager after skipping bill in LV (Nextshark ) Feb 10 : 9 Asian-owned businesses had their windows smashed in Oregon in the last 2 weeks (Yahoo ) Dec 31 - Present : 19 y.o. Chinese American man, Christian Hall, wrongly killed by State Police during mental health crisis - police reports said Chinese man had firearms and was not complying, but video showed 2 empty hands up (Local21News ) Feb 16: 2 Elderly Asian Women Punched in Head in NYC Subway ()Yahoo/NextShark Asian American Support Page 2 Feb 16 : Flushing Asian woman got assaulted - got gashes in her head (ABC7 ) Man was released the next day without bail (Yahoo/NextShark ) Her daughter: https://www.instagram.com/p/CLYarIfDxU6/ -

The Richard Aoki Case: Was the Man Who Armed the Black Panther Party an FBI Informant?

THE RICHARD AOKI CASE: WAS THE MAN WHO ARMED THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AN FBI INFORMANT? by Natalie Harrison A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in History Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida April 2013 THE RICHARD AOKI CASE: WAS THE MAN WHO ARMED THE BLACK PANTHERS AN FBI INFORMANT? by Natalie Harrison This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Christopher Strain, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ____________________________ Dr. Christopher Strain ___________________________ Dr. Mark Tunick ____________________________ Dr. Daniel White ____________________________ Dean Jeffrey Buller, Wilkes Honors College ____________ Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, Dr. Strain for being such a supportive, encouraging and enthusiastic thesis advisor – I could not have done any of this had he not introduced me to Richard Aoki. I would also like to thank Dr. Tunick and Dr. White for agreeing to be my second readers and for believing in me and this project, as well as Dr. Hess for being my temporary advisor when I needed it. And finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for all their support and for never stopping me as I rattled on and on about Richard Aoki and how much my thesis felt like a spy movie.