Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuremberg Chronicle Recycles a Pre-Christian Idea Paul Gross*

ERROR TOWARDS JUDGEMENT. HOW THE NUREMBERG CHRONICLE RECYCLES A PRE-CHRISTIAN IDEA PAUL GROSS* Resumo: Ainda que firmemente baseada numa doutrina cristã, aCrónica de Nuremberga de 1493 abre com uma enumeração de ideias opostas relativamente à origem do mundo e do Homem. Esta primeira passagem é, porém, desde logo rotulada como sendo um erro. Contudo, enquanto o narrador estabelece uma verdade universal, outro erro surge proeminentemente como parte da dimensão factual da crónica. Através da análise intermedial dos textos e de xilogravuras, o presente texto pretende investigar então a forma como este incu- nábulo expõe uma variedade de inverdades com o eventual intuito de integrar uma destas na sua ideologia. Palavras-chave: Crónica do mundo; Incunábulo; Intermedialidade; Early New High German. Abstract: Although firmly grounded in Christian doctrine, the 1493Nuremberg Chronicle opens with an enu- meration of conflicting ideas regarding the origin of the world and of mankind. This initial passage is quickly and effectively done away with by being labelled erroneous. However, while the narrator continues to estab- lish a universal truth, one of the errors reappears, prominently, as part of the chronicle’s facticity. Through the intermedial analysis of texts and woodcuts the paper investigates how the incunable exposes a multitude of falsehoods to eventually integrate one of them into its ideology. Keywords: World chronicle; Incunable; Intermediality; Early New High German. Although firmly grounded in Christian doctrine, the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle opens with an enumeration of conflicting ideas regarding the origin of the world and of man- kind. This initial passage is quickly and effectively done away with by being labelled erro- neous. -

Anti-Semitism: a History

ANTI-SEMITISM: A HISTORY 1 www.counterextremism.com | @FightExtremism ANTI-SEMITISM: A HISTORY Key Points Historic anti-Semitism has primarily been a response to exaggerated fears of Jewish power and influence manipulating key events. Anti-Semitic passages and decrees in early Christianity and Islam informed centuries of Jewish persecution. Historic professional, societal, and political restrictions on Jews helped give rise to some of the most enduring conspiracies about Jewish influence. 2 Table of Contents Religion and Anti-Semitism .................................................................................................... 5 The Origins and Inspirations of Christian Anti-Semitism ................................................. 6 The Origins and Inspirations of Islamic Anti-Semitism .................................................. 11 Anti-Semitism Throughout History ...................................................................................... 17 First Century through Eleventh Century: Rome and the Rise of Christianity ................. 18 Sixth Century through Eighth Century: The Khazars and the Birth of an Enduring Conspiracy Theory AttacKing Jewish Identity ................................................................. 19 Tenth Century through Twelfth Century: Continued Conquests and the Crusades ...... 20 Twelfth Century: Proliferation of the Blood Libel, Increasing Restrictions, the Talmud on Trial .............................................................................................................................. -

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires by William Gertz Runyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mikhail Krutikov, Chair Professor Tomoko Masuzawa Professor Anita Norich Professor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, University of Chicago William Gertz Runyan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3955-1574 © William Gertz Runyan 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee members Tomoko Masuzawa, Anita Norich, Mauricio Tenorio and foremost Misha Krutikov. I also wish to thank: The Department of Comparative Literature, the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for providing the frameworks and the resources to complete this research. The Social Science Research Council for the International Dissertation Research Fellowship that enabled my work in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Tamara Gleason Freidberg for our readings and exchanges in Coyoacán and beyond. Margo and Susana Glantz for speaking with me about their father. Michael Pifer for the writing sessions and always illuminating observations. Jason Wagner for the vegetables and the conversations about Yiddish poetry. Carrie Wood for her expert note taking and friendship. Suphak Chawla, Amr Kamal, Başak Çandar, Chris Meade, Olga Greco, Shira Schwartz and Sara Garibova for providing a sense of community. Leyenkrayz regulars past and present for the lively readings over the years. This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the support of my family, not least my mother who assisted with formatting. -

On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities In

“Go eat a bat, Chang!”: On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19 Fatemeh Tahmasbi Leonard Schild Chen Ling Binghamton University CISPA Boston University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn Gianluca Stringhini Yang Zhang Binghamton University Boston University CISPA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Savvas Zannettou Max Planck Institute for Informatics [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives in COVID-19, Sinophobia, Hate Speech, Twitter, 4chan unprecedented ways. In the face of the projected catastrophic conse- ACM Reference Format: quences, most countries have enacted social distancing measures in Fatemeh Tahmasbi, Leonard Schild, Chen Ling, Jeremy Blackburn, Gianluca an attempt to limit the spread of the virus. Under these conditions, Stringhini, Yang Zhang, and Savvas Zannettou. 2021. “Go eat a bat, Chang!”: the Web has become an indispensable medium for information ac- On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the quisition, communication, and entertainment. At the same time, Face of COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (WWW ’21), unfortunately, the Web is being exploited for the dissemination April 19–23, 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages. of potentially harmful and disturbing content, such as the spread https://doi.org/10.1145/3442381.3450024 of conspiracy theories and hateful speech towards specific ethnic groups, in particular towards Chinese people and people of Asian 1 INTRODUCTION descent since COVID-19 is believed to have originated from China. -

The Resurgence of Antisemitic Discourse in Poland Rafał Pankowski

Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/23739770.2018.1492781 The Resurgence of Antisemitic Discourse in Poland Rafał Pankowski Rafał Pankowski is an associate professor in sociology at Warsaw’s Collegium Civitas University and a co-founder of the Nigdy Wiecej̨ [Never Again] Association, which monitors and combats antisemitism and xenophobia. His books include The Populist Radical Right in Poland (2010) and the forthcoming Poland: Inventing the Nation. The surge of hostility to Jews and the Jewish State in the Polish media and politics in early 2018 took many observers by surprise. For some, it was shocking to witness a virtual tidal wave of antisemitism in the mainstream discourse of one of the largest member states of the European Union—on territory which, during the German occupation, was the epicenter of the Holocaust. It was also a great shock because for many years, bilateral relations between Poland and Israel had been especially cordial and fruitful. While the history of antisemitism in Poland is relatively well known and has been thoroughly researched, few observers adequately assessed its potential as a tool with which to whip up the masses in contemporary Polish society. As late as Feb- ruary 4, 2018, Jonny Daniels, a controversial Anglo-Israeli public relations specialist frequently quoted in the Polish media on Jewish issues, boldly declared, “There is no such thing as Polish antisemitism.”1 Daniels, who mysteriously sur- faced in Poland after the elections in 2015 that brought the radical, right-wing Prawo i Sprawiedliwosċ́(PiS) party to power, became the Orthodox Jewish poster boy of the Polish right. -

FINDING AID to the RARE BOOK LEAVES COLLECTION, 1440 – Late 19/20Th Century

FINDING AID TO THE RARE BOOK LEAVES COLLECTION, 1440 – Late 19/20th Century Purdue University Libraries Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center 504 West State Street West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2058 (765) 494-2839 http://www.lib.purdue.edu/spcol © 2013 Purdue University Libraries. All rights reserved. Processed by: Kristin Leaman, August 27, 2013 Descriptive Summary Title Rare Book Leaves collection Collection Identifier MSP 137 Date Span 1440 – late 19th/early 20th Century Abstract The Rare Book Leaves collection contains leaves from Buddhist scriptures, Golden Legend, Sidonia the Sorceress, Nuremberg Chronicle, Codex de Tortis, and an illustrated version of Wordsworth’s poem Daffodils. The collection demonstrates a variety of printing styles and paper. This particular collection is an excellent teaching tool for many classes in the humanities. Extent 0.5 cubic feet (1 flat box) Finding Aid Author Kristin Leaman, 2013 Languages English, Latin, Chinese Repository Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, Purdue University Libraries Administrative Information Location Information: ASC Access Restrictions: Collection is open for research. Acquisition It is very possible Eleanore Cammack ordered these Information: rare book leaves from Dawson’s Book Shop. Cammack served as a librarian in the Purdue Libraries. She was originally hired as an order assistant in 1929. By 1955, she had become the head of the library's Order Department with a rank of assistant professor. Accession Number: 20100114 Preferred Citation: MSP 137, Rare Book Leaves collection, Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries Copyright Notice: Purdue Libraries 7/7/2014 2 Related Materials MSP 136, Medieval Manuscript Leaves collection Information: Collection of Tycho Brahe engravings Collection of British Indentures Palm Leaf Book Original Leaves from Famous Books Eight Centuries 1240 A.D.-1923 A.D. -

And the Florida State University Seminoles?): the Rt Ademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies Jack Achiezer Guggenheim [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Florida State University College of Law Florida State University Law Review Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 10 1999 Renaming the Redskins (and the Florida State University Seminoles?): The rT ademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies Jack Achiezer Guggenheim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jack A. Guggenheim, Renaming the Redskins (and the Florida State University Seminoles?): The Trademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies, 27 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 287 (1999) . http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol27/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW RENAMING THE REDSKINS (AND THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SEMINOLES?): THE TRADEMARK REGISTRATION DECISION AND ALTERNATIVE REMEDIES Jack Achiezer Guggenheim VOLUME 27 FALL 1999 NUMBER 1 Recommended citation: Jack Achiezer Guggenheim, Renaming the Redskins (and the Florida State University Seminoles?): The Trademark Registration Decision and Alternative Remedies, 27 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 287 (1999). RENAMING THE REDSKINS (AND THE FLORIDA STATE SEMINOLES?): THE TRADEMARK REGISTRATION DECISION AND ALTERNATIVE REMEDIES JACK ACHIEZER GUGGENHEIM* I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................287 -

1 a Place Is Carefully Constructed: Reading the Nuremberg Cityscape

A Place is Carefully Constructed: Reading the Nuremberg Cityscape in the Nuremberg Chronicle Kendra Grimmett A Sense of Place May 3, 2015 In 1493 a group of Nuremberg citizens published the Liber Chronicarum, a richly illustrated printed book that recounts the history of the world from Creation to what was then present day.1 The massive tome, which contains an impressive 1,809 woodcut prints from 645 different woodblocks, is also known as the Nuremberg Chronicle. This modern English title, which alludes to the book’s city of production, misleadingly suggests that the volume only records Nuremberg’s history. Even so, I imagine that the men responsible for the book would approve of this alternate title. After all, from folios 99 verso through 101 recto, the carefully constructed visual and textual descriptions of Nuremberg and its inhabitants already unabashedly favor the makers’ hometown. Truthfully, it was common in the final decades of the fifteenth century for citizens’ civic pride and local allegiance to take precedence over their regional or national identification.2 This sentiment is strongly stated in the city’s description, which directly follows the large Nuremberg print spanning folios 99 verso and 100 recto (fig. 1). The Chronicle specifies that although there was doubt whether Nuremberg was Franconian or Bavarian, “Nurembergers neither wished to be 1 Scholarship on the Nuremberg Chronicle is extensive. See, for instance: Stephanie Leitch, “Center the Self: Mapping the Nuremberg Chronicle and the Limits of the World,” in Mapping Ethnography in Early Modern Germany: New Worlds in Print Culture (Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 17-35; Jeffrey Chipps Smith, “Imaging and Imagining Nuremberg,” in Topographies of the Early Modern City, ed. -

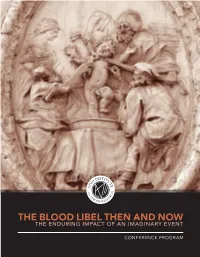

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

Pro-Football, Inc. V. Blackhorse

Case 1:14-cv-01043-GBL-IDD Document 71 Filed 02/26/15 Page 1 of 45 PageID# 1176 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA ALEXANDRIA DIVISION PRO-FOOTBALL, INC., Plaintiff, Civil Action No.: 1:14-cv-1043-GBL-IDD v. AMANDA BLACKHORSE, MARCUS BRIGGS-CLOUD, PHILLIP GOVER, JILLIAN PAPPAN and COURTNEY TSOTIGH, Defendants. DEFENDANTS’ MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF THEIR MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON COUNTS 1, 2, AND 7 Jesse A. Witten (pro hac vice) Jeffrey J. Lopez (VA Bar No. 51058) Adam Scott Kunz (VA Bar No. 84073) Tore T. DeBella (VA Bar No. 82037) Jennifer T. Criss (VA Bar No. 86143) DRINKER BIDDLE & REATH LLP 1500 K Street, N.W., Suite 1100 Washington, D.C. 20005-1209 Telephone: (202) 842-8800 Facsimile: (202) 842-8465 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Defendants Amanda Blackhorse, Marcus Briggs-Cloud, Phillip Gover, Jillian Pappan and Courtney Tsotigh Case 1:14-cv-01043-GBL-IDD Document 71 Filed 02/26/15 Page 2 of 45 PageID# 1177 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 1 PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................ 3 THE BLACKHORSE RECORD AND SUPPLEMENTATION ................................................. 4 MATERIAL FACTS AS TO WHICH THERE IS NO GENUINE ISSUE ............................... 5 A. PFI Adopted The Current Team Name In 1933 To Avoid Confusion With The Boston Braves Baseball Team, Not To Honor Native Americans. ................... 5 B. Dictionaries, Reference Works, Other Written Sources, and Native Americans Expressly Recognize the Disparaging Nature Of The Term “Redskin.” ................................................................................................................. 6 1. Dictionaries ...................................................................................... -

Comprehending Antisemitism Through the Ages: Introduction

Kerstin Mayerhofer and Armin Lange Comprehending Antisemitism through the Ages: Introduction Robert Wistrich’sdefinition of antisemitism as the “longest hatred”¹ carries as much weight now as it did thirty years ago, when Wistrich published his land- mark study. Today, in our contemporary societies and culture, antisemitism is on the rise, and its manifestations are manifold. Antisemitic hate crimes have spiked in recent decades, and antisemitic stereotypes, sentiments, and hate speech have permeated all parts of the political spectrum. In order to effectively counteract the ever-growingJew-hatred of our times, it is important to recognise the traditions thathavefed antisemitism throughout history.Antisemitism is an age-old hatreddeeplyembeddedinsocieties around the globe. While the inter- net and modern media have contributed beyond measure to the increase of Jew- hatred in all parts of the world, the transformation processes thatantisemitism has been undergoing through the ages remain the same. Acorecondition of an- tisemitism is its versatile nature and adaptability,both of which can be traced through all periods of time. Current-day antisemitism is shaped and sustained not onlybypowerful precedents but also reflects common fears and anxieties that our societies are faced with in aworld that is ever changingand where the changes run even faster todaythaneverbefore. Historical awareness of the nature of antisemitism, therefore, is more important than ever.The present volume, thus, wantstohelp raise this awareness.Its articles tracethe history of antisemitismand the tradition of antisemitic stereotypes through the ages. It documents various manifestations of antisemitism over time and reflects on the varyingmotivations for antisemitism.Assuch, these contributions shed light on socio-culturaland socio-psychological processes that have led to the spike of antisemitism in various periods of time and in varyingintensity.In this way, they can help to establish methods and policies to not onlytocounter current antisemitic manifestations but also to combat them. -

Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary the Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation Would Like to Honour And

Lan- guage De- Coded Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary The Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation would like to honour and acknowledgeTreaty aknoledgment all that reside on the traditional Treaty 7 territory of the Blackfoot confederacy. This includes the Siksika, Kainai, Piikani as well as the Stoney Nakoda and Tsuut’ina nations. We further acknowledge that we are also home to many Métis communities and Region 3 of the Métis Nation. We conclude with honoring the city of Calgary’s Indigenous roots, traditionally known as “Moh’Kinsstis”. i Contents Introduction - The purpose Themes - Stigmatizing and power of language. terminology, gender inclusive 01 02 pronouns, person first language, correct terminology. -ISMS Ableism - discrimination in 03 03 favour of able-bodied people. Ageism - discrimination on Heterosexism - discrimination the basis of a person’s age. in favour of opposite-sex 06 08 sexuality and relationships. Racism - discrimination directed Classism - discrimination against against someone of a different or in favour of people belonging 10 race based on the belief that 14 to a particular social class. one’s own race is superior. Sexism - discrimination Acknowledgements 14 on the basis of sex. 17 ii Language is one of the most powerful tools that keeps us connected with one another. iii Introduction The words that we use open up a world of possibility and opportunity, one that allows us to express, share, and educate. Like many other things, language evolves over time, but sometimes this fluidity can also lead to miscommunication. This project was started by a group of diverse individuals that share a passion for inclusion and justice.