The Etymology of Laz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g. -

Russian & East European Studies

We’ve RUSSIANoffered the Raleigh & community EAST Contact spaceEUROPEAN-saving solutions for STUDIESthe past 10 Information DEPARTMENT OF years. We recommend Northwind Traders Slavic Languages and Literatures SLAVIC Northwestern University The U.S. “Needs More Russia Kresge Hall, 3-305 Experts” — The Washington Post 1880 Campus Drive LANGUAGES & Evanston, IL 60201 LITERATURES Explore Russian and East European Russian Studies (REES) at Northwestern! Kashubian Belarussian Polish Lower Sorbian, Learn about our new REES major Lusatian Silesian Ukrainian Upper and minor! Czech Slovak Ruthenian Why is the most popular class at NU Slovene Prof. Saul Morson’s Introduction to Croatian Bosnian Serbian Russian Literature? Bulgarian Macedonian German Chancellor Angela Merkel knows Russian...How about you? Northwestern Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Director of Undergraduate Studies Martina Kerlova [email protected] Department Chair Gary Saul Morson [email protected] Department Administrator Elizabeth Murray [email protected] What is he really saying??? Learn Russian and find out! http://www.slavic.northwestern.edu WHY RUSSIAN & EAST COURSE OFFERINGS COURSE OFFERINGS EUROPEAN STUDIES? 2020-2021 2020-2021 FALL QUARTER 2020 There are many reasons why students may wish to SLAVIC 222: Slavic Civilizations: The RUSSIAN 101-1: Elementary Russian sample courses in Russian, Polish, and Czech Balkans (LING 222) languages, literatures and cultures, offered through RUSSIAN 102-1: Intermediate Russian SLAVIC 255: -

Department of Slavic and Eurasian Languages and Literatures 1

Department of Slavic and Eurasian Languages and Literatures 1 Department of Slavic Placement Students may establish eligibility for enrollment in the second course in Polish, Russian, or Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian by having earned and Eurasian Languages college credit in the first course in that language or by having studied the language in high school. Students with previous study should contact the and Literatures department to arrange a consultation about enrollment at the appropriate level. The Department of Slavic and Eurasian Languages & Literatures offers a complete curriculum of language, culture, literature, and linguistics Retroactive Credit courses for students interested not only in Russian, but also in Polish, Students with no prior college or university Russian course credit are Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, Slovene, Ukrainian, and Turkish languages eligible for retroactive credit according to this formula: and cultures. The department also offers occasional coursework and independent study in Czech and other East European languages. • 3 hours of retroactive credit are awarded to a student with 2 or 3 years of high school Russian who enrolls initially at KU in a third-level The department offers three degrees: the B.A., the M.A., and the Ph.D. Russian course (RUSS 204) and receives a grade of C or higher. The Bachelor of Arts degree program offers fundamental training in • 6 hours of retroactive credit are awarded to a student with 3 or 4 years language and culture, while graduate training at the Masters and Doctoral of high school Russian who enrolls initially at KU in a fourth-level levels focuses on Russian literature and culture, Slavic linguistics, and/ Russian course (RUSS 208) and receives a grade of C or higher. -

The Common Slavic Element in Russian Culture

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF SLAVIC LANGUAGES SLAVIC STUDIES Slavic Philology Series NIKOLAI TRUBETZKOY THE COMMON SLAVIC ELEMENT IN RUSSIAN CULTURE Edited by Leon Stilman Copyright 1949 by the Ikpartmmt of Slavic Languqp Columk univmity The preparation md publication of the aavsrml seriea of work. wder UyZC -1ES hmrm been madm paseible by m gt~t from the Rockefeller Qoundmtion to the Dapartmat of Slrrie Professof N. Trubetzkoy's study on The Cannon Slavic Eleaent in Russian Culture was included in a volume of his collected writings which appeared in 1927, in Paris, under the general title K #roblcme russkogo scwo#o~~anijo.Tbe article was trans- lated fm the Russian bg a group of graduate students of the Departant of Slavic Languages, Columbia Universi tr, including: Ime Barnsha, Hamball Berger, Tanja Cizevslra, Cawrence G, Jones, Barbara Laxtimer, Henry H. Hebel, Jr., Nora B. Sigerist- Beeson and Rita Slesser, The editor fobad it advisable to eli- atnate a number of passqes and footnotes dealing with minor facts; on the other bad, some additions (mainly chro~ologieal data) were made in a fen iwstances; these additions, ia most instances, were incorporated in tbe text in order to amid overburdening it with footnotes; they are purely factual in nature md affect In no the views and interpretations of tbe author. L. S. CONTENTS I Popular ad literarp lan@=ge.- Land11.de and d1abct.- Pxot+Slavic: itn dlalnte$ratlon: Bouthorn, Weatern and EwGern Slavi0.- Li torarr landuadem: thelr evolutiarr: their cnlatlon to apoken vernsaulam ..... 11 Old Church Slevonle: Its origiao and Its role.- The early reeensLma.- Old Bulgmrian Church Slavonlc and its progaget1on.- Church Blavoaie in Russia: sound changes; the Eastern and Wentern Russian trnditloa: the the second South Slavic influenca: the uakfled Ruseisn rocenaim .......... -

![[Review Of] Die Slavischen Sprachen in Gegenwart Und Geschichte: Sprachstrukturen Und Verwandschaft](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9282/review-of-die-slavischen-sprachen-in-gegenwart-und-geschichte-sprachstrukturen-und-verwandschaft-1509282.webp)

[Review Of] Die Slavischen Sprachen in Gegenwart Und Geschichte: Sprachstrukturen Und Verwandschaft

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Linguistics Faculty Publications Linguistics Winter 2001 [Review of] Die slavischen Sprachen in Gegenwart und Geschichte: Sprachstrukturen und Verwandschaft Mark Richard Lauersdorf University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Repository Citation Lauersdorf, Mark Richard, "[Review of] Die slavischen Sprachen in Gegenwart und Geschichte: Sprachstrukturen und Verwandschaft" (2001). Linguistics Faculty Publications. 58. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub/58 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [Review of] Die slavischen Sprachen in Gegenwart und Geschichte: Sprachstrukturen und Verwandschaft Notes/Citation Information Published in Slavic and East European Journal, v. 45, no. 4, p. 805-806. Dr. Mark Richard Lauersdorf has received the journal's permission for posting this book review online. Dr. Mark Richard Lauersdorf was affiliated with Luther College at the time of publication. This book review is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub/58 Reviews 805 question of iteratives and other noneventive presents. And Dickey's conclusion that Polish, while occupying an intermediate position, is aspectually more like the "eastern" group of languages, is corroborated by contrastive studies that establish aspectual correlations between Polish and Russian literary texts in excess of 90%. I recommend this book as a valuable complement to the field of Slavic aspectology. -

Areal and Diachronic Trends in Argument Flagging Across Slavic Ilja

Areal and diachronic trends in argument flagging across Slavic Ilja A. Seržant,1 Björn Wiemer,2 Eleni Bužarovska,3 Martina Ivanová,4 Maxim Makartsev,5 Stefan Savić,6 Dmitri Sitchinava,7 Karolína Skwarska,8 Mladen Uhlik9 1Institute of Slavonic Studies, Christian-Albrechts-University Kiel, 2Institute of Slavic, Turkic and Circum-Baltic Studies, Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz, 3Ss. Cyril and Methodius University Skopje, 4University of Prešov, 4Ľ. Štúr Institute of Linguistics, Slovak Academy of Sciences, 5Institute of Slavic Studies, Carl von Ossietzky University in Oldenburg, 5Institute of Slavic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow), 6Rhodes University, 7Institute of Russian Languages, Russian Academy of Sciences; School of Linguistics, HSE University, 8Institute of Slavonic Studies of the CAS, 9University of Ljubljana, 9Fran Ramovš Institute of Slovenian Language (Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Science and Arts). Abstract In this pilot study, we examine the variation in the flagging patterns across 10 modern Slavic languages – covering all three major Slavic branches: South, West and East Slavic – and Old Church Slavic. We rely on a database that comprises 825 entries and is based on translation tasks with 46 verb meanings that target verbs with middle-level transitivity prominence. We analyze three main factors: the ratio of flagging alternations (vs. rigid government), transitivity prominence and ratio of nominative marking. We argue that despite high homogeneity in this domain across Slavic, there are clear genealogical and areal trends that explain the distribution of different flagging patterns across Slavic. Thus, when it comes to transitivity prominence, we detected an areal trend that splits Slavic languages into Northeast Slavic (Belarusian, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian) and Southwest Slavic (all other languages), such that the former group shows relatively low and the latter high transitivity prominence. -

Slavic Languages and Literatures, Ph.D. 1

Slavic Languages and Literatures, Ph.D. 1 Croatian) as well as of French or German before attaining dissertator status. More information regarding coursework may be found on the SLAVIC LANGUAGES AND program website. LITERATURES, PH.D. Students complete all requirements for dissertator status by the end of their seventh semester. The graduate program was recently revised, including the dissertation process, to allow for graduation with the Ph.D. Slavic languages and literature at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in six to seven years from the B.A. Students who choose to take a leave of is a national leader of doctoral programs in the field, and welcomes absence for language study may require a longer tenure. students with a B.A./B.S. or M.A. who are interested in all areas of Russian and comparative Slavic prose, poetry, drama, and philosophy. The curriculum offers breadth and depth in a variety of areas of Slavic philology, literature, and culture, and is known for offering a balanced approach to training in teaching, writing, and research. The program is fortunate to count among its faculty, specialists in Czech, Polish, Russian, and Serbo-Croatian languages, literature, and culture, award-winning authors and teachers, and members of editorial boards of leading journals and publication series. Information regarding faculty biographical sketches are available on the program website. In addition to their excellence in teaching and research, professors are unparalleled mentors to graduate students. Students work closely with faculty members on writing, teaching, and publishing. Graduate students are expected to produce publishable articles during their graduate careers, and are provided the guidance and feedback to do so. -

Grammatical Influences (Morphological) of Albanian Language in the Languages of Minorities in the Region of Prizren

E-ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Vol 8 No 3 ISSN 2239-978X September 2018 Social Research . Research Article © 2018 Senad Neziri. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Grammatical Influences (Morphological) of Albanian Language in the Languages of Minorities in the Region of Prizren Senad Neziri, PhD(c) Faculty of Philology, University of Prishtina "Hasan Prishtina" Doi: 10.2478/jesr-2018-0031 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to prove the presence of calques (loan translation) of Albanian language in the languages of minorities (Gorani community, Bosnian community) in the region of Prizren. We will make an effort to provide evidence for the role of Albanian as a donor language through daily contacts with the members of the above-mentioned communities. The corpus of this study will be the edited volume of songs and folk tales from minority areas, respectively from the population of Gorani and Bosnian ethnicity and their dialects. The research will be focused in minority areas in the municipality of Dragash (Sharr) where Gorani people live, as well as in other areas of minority language speakers, mainly in Zhupa, in the municipality of Prizren. The paper will be important in enlightening the facts of using the structure of Albanian, both in the spoken language of the minority community and that of Albanian community. The cases where certain elements of Albanian language are encountered in another language, where Albanian appears as a donor language, will be considered as important. -

A Polemic About the Slavic Origins in Polish Lands

Journal Of Anthropological And Archaeological Sciences DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2021.03.000170 ISSN: 2690-5752 Review Article A polemic about the Slavic Origins in Polish Lands Wojciech J Cynarski* Committee of Scientific Research, Idokan Poland Association, Poland *Corresponding author: Wojciech J Cynarski, Committee of Scientific Research, Idokan Poland Association, Rzeszów, Poland Received: February 04, 2021 Published: March 01, 2021 Abstract So far, representatives of historians and archaeologists have not undertaken an invitation to a substantive polemic. Only on forums and blogs you can find both critical comments and positive references to the content previously published by the author. forum.Meanwhile, subsequent excavations and other studies confirm the cultural proximity of the former Slavs (Lechites) and Scythians, and the presence of Proto-Slavs in Central Europe already in antiquity. Hence the need to speak at the next scientific discussion Keywords: Proto-Slavic History; Autochthonous Theory; Polish Chronicles; Hg R1a1; Language Introduction The scattered research results and theoretical concepts of dishes, weapons and ornaments were to confirm the superiority Slavic ones. of the material culture of the Germanic or Celtic tribes over the of researchers representing various fields of science are like According to allochtonists, the beginnings of statehood and the puzzles with which you do not know what to do. The author made Slavic language (old-Slavonic) are indicated at - 6-9 c. AD [10,11], i.e., epistemological work on the basis of assembling puzzles into larger conceptual scope [1]. The key is classical logic and the principle of and larger images and attempts to interpret issues of ever wider systemic approaches to the studied reality. -

Languages Are Wealth: the Sprachbund As Linguistic Capital Author(S): Victor A

Languages are wealth: The Sprachbund as linguistic capital Author(s): Victor A. Friedman Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), pp. 163-178 General Session and Thematic Session on Language Contact Editors: Kayla Carpenter, Oana David, Florian Lionnet, Christine Sheil, Tammy Stark, Vivian Wauters Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/. The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage, the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. Languages are Wealth: The Sprachbund as Linguistic Capital* VICTOR A. FRIEDMAN University of Chicago My title is a translation from the Aromanian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Meglenoromanian versions of a Balkan proverb followed by a nod to Bourdieu (1991). The folk saying occurs in various forms in all the Balkan languages except Greek.1 Thus, for example, the Albanian and Romani equivalents translate ‘the more languages you speak, the more people you are worth’.2 Turkish and Balkan Judezmo speakers both use the Turkish version: bir lisan, bir insan; iki lisan, iki insan ‘one language, one person; two languages, two people.’ Folk wisdom valorizing multilingualism can be taken as indicative of the conditions under which a sprachbund can develop, and the exception can be taken as symp- tomatic of the pressures to eliminate language contact.3 I would like elaborate here on these issues by contributing to two important points made by Eric P. Hamp at the Third Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (Hamp 1977) and by adding two more. -

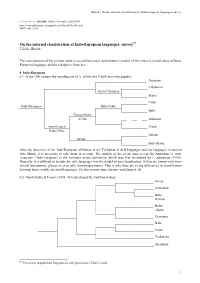

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3.