Japanese Production Networks in Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Groups, Networks, and Embeddedness: Innovation and Implementation Alliances in Japanese Electronics, 1985–1998

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Business groups, networks, and embeddedness: innovation and implementation alliances in Japanese electronics, 1985–1998 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3dq9f64q Journal Industrial and Corporate Change, 26(3) Authors Lincoln, James R Guillot, Didier Sargent, Matthew Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Industrial and Corporate Change Advance Access published September 10, 2016 Industrial and Corporate Change, 2016, 1–22 doi: 10.1093/icc/dtw037 Original article Business groups, networks, and embeddedness: innovation and implementation alliances in Japanese electronics, 1985–1998 James R. Lincoln,1,* Didier Guillot,2 and Matthew Sargent3 1Walter A. Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. e-mail: [email protected], 2Fukui Prefectural University, Fukui 910-1195, Japan. e-mail: [email protected] Downloaded from and 3USC Digital Humanities Program, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA. e-mail: [email protected] *Main author for correspondence. http://icc.oxfordjournals.org/ Abstract This paper examines the changing process of strategic alliance formation in the Japanese electronics industry between 1985 and 1998. With data on 123–135 Japanese electronics/electrical machinery makers, we use a dyad panel regression methodology to address hypotheses drawn largely from em- beddedness theory on how the firms’ horizontal and vertical keiretsu business group affiliations and prior alliance networks supported and constrained partner choice in new R&D (innovation) and nonR&D (implementation) domestic economy alliances. We find that in the first half of our series (1985–1991; the “preburst” period), keiretsu served as infrastructure for new strategic alliances that by guest on September 11, 2016 had both innovation (R&D) and implementation (nonR&D) goals. -

To Our Shareholders and Customers Issues We Faceinfiscal2000

To Our Shareholders and Customers — The Dawn of a New Era — Review of Fiscal 1999 For the Japanese financial sector, fiscal 1999 During fiscal 1999, we strengthened our man- marked the start of a totally new era in the his- agement infrastructure and corporate structure tory of finance in Japan. by improving business performance, restructur- In August 1999, The Fuji Bank, Limited, ing operations, strengthening risk management The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, Limited, and The and managing consolidated business activities Industrial Bank of Japan, Limited, reached full under a stronger group strategy. agreement to consolidate their operations into a comprehensive financial services group to be • Improving Business Performance called the Mizuho Financial Group. In the fol- We have identified the domestic corporate and lowing six months after the announcement, retail markets as our priority business areas. several other major Japanese financial institu- Our goals in these markets are to enhance our tions announced mergers and consolidations of products and services to meet the wide-ranging one form or another. needs of our customers, and to improve cus- At the same time, conditions in the financial tomer convenience by using information tech- sector changed dramatically as foreign-owned nology to diversify our service channels. financial institutions began in earnest to With respect to enhancing products and expand their presence in Japan, companies services, we focused on services provided to from other sectors started to move into the members of the Fuji First Club, a membership To Our Shareholders and Customers To financial business, and a number of Internet- reward program that offers special benefits to based strategic alliances were formed across dif- member customers, and on our product lineup ferent sectors and industries. -

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fuji Bank Group

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fuji Bank Group Balance Sheet Thousands of Thousands of Millions of yen U.S. dollars Millions of yen U.S. dollars March 31, 1998 1997 1998 March 31, 1998 1997 1998 ASSETS LIABILITIES AND STOCKHOLDERS’ EQUITY Liabilities Cash and Due from Banks................................................................. ¥ 00,000,0002,821,634 ¥00,000,0004,341,701 $000,000,00021,359,834 Deposits (Note 8) .............................................................................. ¥ 00,000,00034,552,361 ¥00,000,00038,649,481 $000,000,000261,562,164 Call Money and Bills Sold ................................................................. 3,755,273 4,310,517 28,427,509 Call Loans and Bills Purchased .......................................................... 1,453,230 2,230,223 11,000,989 Trading Liabilities .............................................................................. 2,057,167 — 15,572,803 Borrowed Money (Note 9)................................................................ 2,947,169 2,252,185 22,310,138 Commercial Paper and Other Debt Purchased................................... 43,216 188,430 327,152 Foreign Exchange.............................................................................. 113,221 82,000 857,087 Trading Assets (Note 3) ..................................................................... 3,265,412 — 24,719,248 Bonds and Notes (Note 10) ............................................................... 1,657,224 1,322,494 12,545,228 Convertible Bonds (Note 11) ........................................................... -

International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 4 Issue 2 Fall Fall 1982 International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert W. Dziubla, International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model, 4 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 422 (1982) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business International Trading Companies: Building On The Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla* Passageof the Export Trading Company Act of 1982provides new op- portunitiesfor American business to organize and operate general trading companies. Afterpresenting a thorough history and description of the Japa- nese sogoshosha, Mr. Dziubla gives several compelling reasonsfor Ameri- cans to establish export trading companies. He also examines the changes in United States banking and antitrust laws that have resultedfrom passage of the act, and offers suggestionsfor draftingguidelines, rules, and regula- tionsfor the Export Trading Company Act. For several years, American legislators and businessmen have warned that if America is to balance its international trade-and in particular offset the cost of importing billions of dollars worth of oil- she must take concrete steps to increase her exporting capabilities., On October 8, 1982, the United States took just such a step when President Reagan signed into law the Export Trading Company Act of 1982,2 which provides for the development of international general trading companies similar to the ones used so successfully by the Japanese. -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Nber Working Paper Series Did Mergers Help Japanese

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DID MERGERS HELP JAPANESE MEGA-BANKS AVOID FAILURE? ANALYSIS OF THE DISTANCE TO DEFAULT OF BANKS Kimie Harada Takatoshi Ito Working Paper 14518 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14518 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2008 The paper started as a joint project with Dr. Kelly Wang when she was Assistant Professor at University of Tokyo. The authors are grateful to her for her help in providing us with computer programs and in discussion the ways to apply her methods to the Japanese banking data. Upon Dr. Wang's departure from the University of Tokyo, the project was carried on by the current two authors with full consent from Dr. Wang. The current two authors take responsibility for any remaining errors. Mr. Shuhei Takahashi provided us with superb research assistance. We are grateful for financial support from Nomura foundation for social science and Chuo University for Special Research. We are also grateful for helpful discussions with Masaya Sakuragawa, Naohiko Baba, Satoshi Koibuchi, Woo Joong Kim, Joe Peek, Kazuo Kato and for insigutful comments from participants in Asia pacific Economic Association in Hong Kong in 2007, Japan Economic Association in 2008, NBER Japan Group Meeting in 2008 and Asian FA-NFA 2008 International Conference. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. -

Fuyo General Lease Co., Ltd.<8424>

COMPANY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS REPORT Fuyo General Lease Co., Ltd. 8424 Tokyo Stock Exchange First Section 17-Feb.-2020 FISCO Ltd. Analyst Ikuo Shibata FISCO Ltd. http://www.fisco.co.jp 02 COMPANY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS REPORT FISCO Ltd. http://www.fisco.co.jp Fuyo General Lease Co., Ltd. 17-Feb.-2020 8424 Tokyo Stock Exchange First Section https://www.fgl.co.jp/eng/ ■ Index ■Summary --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 01 1. Company profile .......................................................................................................................................... 01 2. Medium-term management plan ................................................................................................................. 01 3. Summary of 1H FY3/20 results ................................................................................................................... 01 4. FY3/20 results outlook ................................................................................................................................ 02 ■Company profile --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 03 1. Business overview ...................................................................................................................................... 03 2. History ....................................................................................................................................................... -

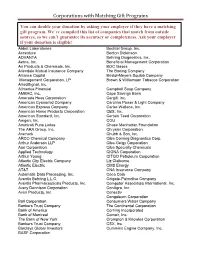

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs You can double your donation by asking your employer if they have a matching gift program. We’ve compiled this list of companies that match from outside sources, so we can’t guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Ask your employer if your donation is eligible! Abbot Laboratories Bechtel Group, Inc. Accenture Becton Dickinson ADVANTA Behring Diagnostics, Inc. Aetna, Inc. Beneficial Management Corporation Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. BOC Gases Allendale Mutual Insurance Company The Boeing Company Alliance Capital Bristol-Meyers Squibb Company Management Corporation, LP Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation AlliedSignal, Inc. Allmerica Financial Campbell Soup Company AMBAC, Inc. Cape Savings Bank Amerada Hess Corporation Cargill, Inc. American Cyanamid Company Carolina Power & Light Company American Express Company Carter-Wallace, Inc. American Home Products Corporation CBS, Inc. American Standard, Inc. Certain Teed Corporation Amgen, Inc. CGU Ammirati Puris Lintas Chase Manhattan Foundation The ARA Group, Inc. Chrysler Corporation Aramark Chubb & Son, Inc. ARCO Chemical Company Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp. Arthur Anderson LLP Ciba-Geigy Corporation Aon Corporation Ciba Specialty Chemicals Applied Technology CIGNA Corporation Arthur Young CITGO Petroleum Corporation Atlantic City Electric Company Liz Claiborne Atlantic Electric CMS Energy AT&T CNA Insurance Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Coca Cola Aventis Behring L.L.C. Colgate-Palmolive Company Aventis Pharmaceuticals Products, Inc. Computer Associates International, Inc. Avery Dennison Corporation ConAgra, Inc. Avon Products, Inc. Conectiv Congoleum Corporation Ball Corporation Consumers Water Company Bankers Trust Company The Continental Corporation Bank of America Corning Incorporated Bank of Montreal Comair, Inc. The Bank of New York Crompton & Knowles Corporation Bankers Trust Company CSX, Inc. -

ISSN 1045-6333 the FABLE of the KEIRETSU Yoshiro Miwa J. Mark Ramseyer Discussion Paper No. 316 3/2001 Harvard Law School Cambri

ISSN 1045-6333 THE FABLE OF THE KEIRETSU Yoshiro Miwa J. Mark Ramseyer Discussion Paper No. 316 3/2001 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 The Center for Law, Economics, and Business is supported by a grant from the John M. Olin Foundation. This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ JEL: G3, K2, L1, P5 Address correspondence to: University of Tokyo Faculty of Economics 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo FAX: 03-5841-5521 [email protected] [email protected] The Fable of the Keiretsu by Yoshiro Miwa & J. Mark Ramseyer* Abstract: Central to so many accounts of post-war Japan, the keiretsu corporate groups have never had economic substance. Conceived by Marxists committed to locating "domination" by "monopoly capital," they found an early audience among western scholars searching for evidence of culture-specific group behavior in Japan. By the 1990s, they had moved into mainstream economic studies, and keiretsu dummies appeared in virtually all econometric regressions of Japanese industrial or corporate structure. Yet the keiretsu began as a figment of the academic imagination, and they remain that today. The most commonly used keiretsu roster first groups large financial institutions by their pre-war antecedents. It then assigns firms to a group if the sum of its loans from those institutions exceeds the amount it borrows from the next largest lender. Other rosters start by asking whether firm presidents meet occasionally with other presidents for lunch. Regardless of the definition used, cross-shareholdings were trivial even during the years when keiretsu ties were supposedly strongest, and membership has only badly proxied for "main bank" ties. -

Characteristics of Japanese Industrial Groups and Their Potential Impact on U

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Empirical Studies of Commercial Policy Volume Author/Editor: Robert E. Baldwin, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press, 1991 Volume ISBN: 0-226-03569-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bald91-1 Conference Date: March 16-17, 1990 Publication Date: January 1991 Chapter Title: Characteristics of Japanese Industrial Groups and Their Potential Impact on U. S . - Japanese Trade Chapter Author: K.C. Fung Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c6712 Chapter pages in book: (p. 137 - 168) 5 Characteristics of Japanese Industrial Groups and Their Potential Impact on U. S .- Japanese Trade K. C. Fung 5.1 Introduction Given the economic importance of the two nations, the economic relation- ship between the United States and Japan is perhaps the most significant bilat- eral economic linkage in the world economy today. Unfortunately, the domi- nant feature of the relationship in recent years has been disputes about trade. The core of the problem is undoubtedly the persistent trade imbalance be- tween the two nations. The magnitude of the trade imbalance remains large, The United States ran a merchandise trade deficit of over $1 18.5 billion in 1988, and $109 billion in 1989. Japan had a global trade surplus of $78.3 billion in 1988 and $65 billion in 1989. On a bilateral level, the trade imbalance between the United States and Japan was $5 1.8 billion in 1988 and $49 billions in 1989. -

The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank,Limited the Fuji Bank,Limited the Industrial Bank of Japan,Limited

QX/MZHO Interim 2000入稿原稿 01.1.23 7:26 PM ページ c1 (W) 570pt x (H) 648pt 2000 INTERIM REPORT The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank,Limited The Fuji Bank,Limited The Industrial Bank of Japan,Limited c1 QX/MZHO Interim 2000入稿原稿 01.1.23 7:26 PM ページ c2 (W) 570pt x (H) 648pt To Our Shareholders and Customers Mizuho Holdings Established We are pleased to issue our first financial report as the newly formed bank holding company for three of Japan’s leading financial institutions—The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, Limited (“DKB”), The Fuji Bank, Limited (“Fuji Bank”), and The Industrial Bank of Japan, Limited (“IBJ”). Mizuho Holdings, Inc. (“MHHD”), was established through a stock-for-stock exchange on September 29, 2000, thus marking the formal inauguration of the Mizuho Financial Group (“MHFG”). Following this, on October 1, 2000, Mizuho Securities Co., Ltd. (“Mizuho Securities”), and Mizuho Trust & Banking Co., Ltd. (“Mizuho Trust”), were formed through the consolidation of subsidiaries of the three banks. MHHD initiated the management of the entire group by means of a Business Unit (“BU”) structure operating across the three banks. Under this structure, DKB, Fuji Bank, IBJ, Mizuho Securities, and Mizuho Trust operate as the five core member companies of MHFG. With legislative and tax code changes for corporate splits in Japan expected to be implemented by spring 2002, we will combine and reorganize the existing operations into legally separate subsidiaries, i.e., Mizuho Bank, Ltd., Mizuho Corporate Bank, Ltd., Mizuho Securities, and Mizuho Trust, according to customer segments and business lines under MHHD. -

Data1209 All.Pdf

We aim to become “the most trusted financial institution.” This slogan conveys Mizuho's unified commitment to implementing the reforms necessary for us to achieve this goal. We want to work with our customers to help them build a brighter future. The following ideals are represented by the term “One MIZUHO”: Group Unity Sharing awareness among management and employees of the group of the importance of working with customers to help them build a brighter future. New Organizational Structure Utilizing an advanced, group-wide management structure to fully leverage our strengths as a full-line financial services group which includes banking, trust, securities, and asset management arms to offer our customers a diverse range of high quality services. To Be No. 1 Aiming to become “the most trusted financial institution” by our customers. Only One Aiming to become our customers' sole financial institution of choice. Everything we do, we do for our customers. We remain committed to the ideals represented by our sub slogan as we work together as a group to implement the reforms necessary for us to achieve our goal of becoming “the most trusted financial institution.” 2 Corporate Profile The Mizuho Financial Group (MHFG) is one of the largest financial institutions in the world, offering a broad range of financial services including banking, securities, trust and asset management, credit card, private banking, venture capital through its group companies. The group has approximately 56,000 staff working in approximately 940 offices inside and outside Japan, and total assets of over US$2.1 trillion (as of September 2012).