Devotion to a Goddess in Contemporary India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

The Miracle of Self Realization: Why God, Guru and the Self Are One and the Same?

WORKING PAPER NO: 434 The Miracle of Self Realization: Why God, Guru and the Self are One and the Same? Ramnath Narayanaswamy Professor Economics & Social Science Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 Ph: 080-26993137 [email protected] Year of Publication -November 2013 The Miracle of Self Realization: Why God, Guru and the Self are One and the Same? Abstract This contribution is rooted in Indian spirituality, more specifically in the tradition of Advaita Vedanta or the philosophy of non-dualism. In this paper, an attempt is made to outline the biggest miracle of all, namely, the miracle of self realization. In Indian spirituality, it constitutes the very purpose of our birth as human beings. This purpose lies in self revelation and if this is not successfully pursued then the current life is said to have been wasted from a spiritual point of view. We discuss three concepts that are central to Indian spirituality. These include, God, Guru and the Self. Our purpose is to demonstrate that all three terms designate one Reality. We anchor ourselves on the pronouncements of Sri Ramana Maharishi, who was one of the greatest sages of India, who left his mortal coil in the last century. For this purpose, we have selected some excerpts from one of the most celebrated works in Ramana literature known as Talks which was put together by Sri Mungala Venkatramiah and subsequently published by Sri Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai. It is a veritable Bible for Ramana devotees and widely regarded as such. The central challenge in all management is realizing the nature of oneself. -

The Humanitarian Initiatives

® THE HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVES OF SRI MATA AMRITANANDAMAYI DEVI (MATA AMRITANANDAMAYI MATH) embracing the world ® is a global network of charitable projects conceived by the Mata Amritanandamayi Math (an NGO with Special Consultative Status to the United Nations) www.embracingtheworld.org © 2003 - 2013 Mata Amritanandamayi Mission Trust, Amritapuri, Kollam, 690525, India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, reproduced, transcribed or translated into any language, in any form, by any means without prior agreement and written permission of the publisher. Edition 12, January 2013 Amma | 06 Disaster Relief | 15 Empowering Women | 34 Building Homes | 38 Community Outreach | 45 Care Homes for Children | 51 Public Health | 56 Education for Everyone | 59 Research for a Better World | 66 Healthcare | 73 Fighting Hunger | 82 Green Initiatives | 85 Amrita Institutions | 88 my religion Contacts | 95 is love Amma The world should know that a life dedicated to selfless love and service is possible. Amma Amma’s Life Amma was born in a remote coastal village in Amma was deeply affected by the profound Each of Embracing the World’s projects has Kerala, South India in 1953. Even as a small suffering she witnessed. According to Hindu- been initiated in response to the needs of girl, she drew attention with the many hours she ism, the suffering of the individual is due to the world’s poor who have come to unburden spent in deep meditation on the seashore. She his or her own karma — the results of actions their hearts to Amma and cry on her shoulder. -

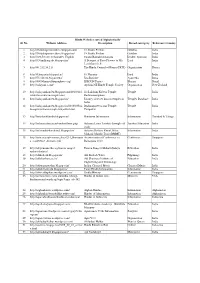

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Around the Country with Modi

AROUND THE COUNTRY WITH MODI The Gujarat chief minister’s itinerary since he was declared BJP's prime ministerial candidate BJP prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi at an election rally in Udaipur on Saturday PHOTO: PTI POLITICAL Sept 14: Addresses ex-servicemen at Rewari, his KEY EVENTS RALLIES first rally after being declared PM candidate for BJP Sept 21: Addresses the Indian Sept 25: Attends Karyakarta Mahakumbh in diaspora in Tampa, US, via video- Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh along with L KAdvani conference and MP CM Shivraj Singh Chouhan. According to an Sept 30: Inaugurates Bharat Sept 28: estimate, over 500,000 party workers from every Diamond Bourse's Diamond Hall Addresses BJP’s part of the state attended the function Vikas Rally in at Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla Delhi Complex. Lateraddresses the platinum jubilee celebrations of the International Advertising Association in Mumbai Oct 25: Addresses ‘Vijay Oct 14: Delivers a lecture in the US, Shankhnad Rally ‘ in Jhansi Effective Governance in Oct 27: Addresses rally in Hunkaar in Patna's Democracy: Guj Experience, via Oct 26: Gandhi Maidan despite serial blasts ahead of video-conference Addresses his address Oct 18:Delivers the Nani Palkhivala Janjaati Sept 26: Offers prayers at Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Memorial Lecture in Chennai and Morcha releases Arun Shourie's book Sammelan Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. Also visits the royal family of in Udaipur Travancore at Kowdiar Palace and elderly member of the royal Oct 19: Interacts with students in family, Uthradom Thirunal Marthanda Varma. Gandhinagar. Mukesh Ambani Later he also attends 60th birthday celebrations of Satguru Sri and British Petroleum CEO Bob Mata Amritanandamayi Devi in Amritapuri. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Humanitarian Initiatives

HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVES Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi Mata Amritanandamayi Math OUR VOLUNTEERS ARE HELPING PEOPLE IN NEED ON SIX CONTINENTS. North America AFRICA ASIA NORTH AMERICA SOUTH AMERICA EUROPE AUSTRALIA AMMA HAS DONE MORE WORK THAN MANY GOVERNMENTS HAVE EVER DONE FOR THEIR PEOPLE. HER CONTRIBUTION IS ENORMOUS. - Muhammad Yunus 2006 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate & Founder, Grameen Bank + EMBRACINGTHEWORLD.ORG CONTENTS + TAP A CHAPTER TO OPEN The Founder of Embracing the World 4 Basic Needs: Food & Water 13 Basic Needs: Shelter 20 Basic Needs: Healthcare 26 Basic Needs: Education 37 Basic Needs: Livelihood 43 Emergencies 48 Amrita University 55 Environment 61 AYUDH: Our Youth Wing 65 Self-Reliant Villages 69 A Few of Our Centers Around the World 73 + EMBRACINGTHEWORLD.ORG s long as there is enough strength A to reach out to those who come to me, to place my hand on a crying person’s shoulder, I will continue to embrace people. To lovingly caress them, to console and wipe their tears until the end of this mortal frame—this is my wish. - Amma THE FOUNDER OF EMBRACING THE WORLD ri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi—spiritual leader, S humanitarian and visionary—has served the world-community for decades. Known throughout the world simply as Amma, which means mother in her birth language, she imparts wisdom, strength and inspiration to the people who come to see her. Through her extraordinary acts of love, inner strength and self-sacrifice, Amma has endeared herself to millions and inspired thousands to follow in her path of selfless service. TAP FOR THE STORY OF AMMA’S EARLY SEARCH FOR THE MEANING OF SUFFERING OR FIND IT LATER AT: bit.ly/amma-story As a little girl, Amma witnessed firsthand the stark inequality in the world and wondered about the meaning of suffering. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook Event Data Project Department of Political Science Pennsylvania State University Pond Laboratory University Park, PA 16802 http://eventdata.psu.edu/ Philip A. Schrodt (Project Director): < schrodt@psu:edu > (+1)814.863.8978 Version: 1.1b3 March 2012 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.0.1 Events . .1 1.0.2 Actors . .4 2 VERB CODEBOOK 6 2.1 MAKE PUBLIC STATEMENT . .6 2.2 APPEAL . .9 2.3 EXPRESS INTENT TO COOPERATE . 18 2.4 CONSULT . 28 2.5 ENGAGE IN DIPLOMATIC COOPERATION . 31 2.6 ENGAGE IN MATERIAL COOPERATION . 33 2.7 PROVIDE AID . 35 2.8 YIELD . 37 2.9 INVESTIGATE . 43 2.10 DEMAND . 45 2.11 DISAPPROVE . 52 2.12 REJECT . 55 2.13 THREATEN . 61 2.14 PROTEST . 66 2.15 EXHIBIT MILITARY POSTURE . 73 2.16 REDUCE RELATIONS . 74 2.17 COERCE . 77 2.18 ASSAULT . 80 2.19 FIGHT . 84 2.20 ENGAGE IN UNCONVENTIONAL MASS VIOLENCE . 87 3 ACTOR CODEBOOK 89 3.1 HIERARCHICAL RULES OF CODING . 90 3.1.1 Domestic or International? . 91 3.1.2 Domestic Region . 91 3.1.3 Primary Role Code . 91 3.1.4 Party or Speciality (Primary Role Code) . 94 3.1.5 Ethnicity and Religion . 94 3.1.6 Secondary Role Code (and/or Tertiary) . 94 3.1.7 Specialty (Secondary Role Code) . 95 3.1.8 Organization Code . 95 3.1.9 International Codes . 95 i CONTENTS ii 3.2 OTHER RULES AND FORMATS . 102 3.2.1 Date Restrictions . 102 3.2.2 Actors and Agents . -

Sainthood Joshy Paramthottu"

Journal of Dharma 29, 3 (July-September 2004),351-370 MA TA AMRITANANDAMA YI An Embodiment of the 'Embracing' Sainthood Joshy Paramthottu" 1. Introduction History has witnessed manifold personalities who appear with a special flair of spirituality and charisma to enkindle and rekindle individuals and communities. Simple, insignificant and humble human beings become universal figures by gradually assuming spiritual powers. They emerge to be saints and wonder workers. Are saints born or made? The Bhakti Tradition has its own role in sensitizing the devotional sentiments of the devotees. The number of saints in the Indian tradition is not in any way less in comparing any other traditions of faith and devotion throughout the world. In recent debates we come across an amazing applaud to the saints of New Age Movements. Sanctity and divinity cannot be put into logical scrutiny to get perfect clarity of notions. Faith and reason, however, exist side-by-side enhancing each other in the human search for the real. Most often we fall short of reasoning in our attempt to understand 'Saints' of the times. Among the modern saints of the New Age, Mata Amritanandamayi is unique in various respects, especially in her dual expressions of divine bhavas and her hugging of the devotees to impart her blessings. 2. Amritapuri Amma: A Brief Life Sketch Unearthing of the historical origin and humble beginning is an important factor in the study of saints and persons who claim to have certain divine existence. Amma,1 as she is known among her devotees, was born in 1953, •Josby Paramtbottu cmi holds a Master's in Philosophy from Dharmaram Vidya Kshetram, Bangalore, and is presently a lecturer in the Faculty of Philosophy of the same Institute. -

THE HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVES of Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi (Mata Amritanandamayi Math) OUR VOLUNTEERS ARE HELPING PEOPLE in NEED on SIX CONTINENTS

THE HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVES of Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi (Mata Amritanandamayi Math) OUR VOLUNTEERS ARE HELPING PEOPLE IN NEED ON SIX CONTINENTS. © 2003 - 2016 Mata Amritanandamayi Mission Trust, Amritapuri, Kollam, 690525, India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, reproduced, transcribed or translated into any language, in any form, by any means without prior agreement and written permission of the publisher. Edition 15, May 2016 WHO WE ARE DOING MORE WITH LESS Embracing the World is a global network of humanitarian With the vast majority of our efforts carried out by volunteers, organizations inspired by the India-based humanitarian and zero paid administrators at the national and international initiatives of the Mata Amritanandamayi Math*. levels, we’re able to do more with less. Embracing the World exists to help alleviate the burden of the world’s poor through helping to meet each of their five basic needs — food, shelter, healthcare, education, and livelihood — wherever and whenever possible. We are especially focused on helping to meet these needs in the aftermath of major disasters. Augmenting these efforts, we work in the fields of environ- mental conservation and sustainability to help protect the future of our fragile planet. And through Amrita University, our researchers are innovating new means of delivery of goods, knowledge, information, energy, and healthcare so that we can *Mata Amritanandamayi Math is an NGO with Special get help to those in need here and now, wherever they are. Consultative Status to the United Nations. AMMA HAS DONE MORE WORK THAN MANY GOVERNMENTS HAVE EVER DONE FOR THEIR PEOPLE. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore