Discursive Struggles and Contested Signifiers in a Popular Faith Phenomenon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

The Miracle of Self Realization: Why God, Guru and the Self Are One and the Same?

WORKING PAPER NO: 434 The Miracle of Self Realization: Why God, Guru and the Self are One and the Same? Ramnath Narayanaswamy Professor Economics & Social Science Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 Ph: 080-26993137 [email protected] Year of Publication -November 2013 The Miracle of Self Realization: Why God, Guru and the Self are One and the Same? Abstract This contribution is rooted in Indian spirituality, more specifically in the tradition of Advaita Vedanta or the philosophy of non-dualism. In this paper, an attempt is made to outline the biggest miracle of all, namely, the miracle of self realization. In Indian spirituality, it constitutes the very purpose of our birth as human beings. This purpose lies in self revelation and if this is not successfully pursued then the current life is said to have been wasted from a spiritual point of view. We discuss three concepts that are central to Indian spirituality. These include, God, Guru and the Self. Our purpose is to demonstrate that all three terms designate one Reality. We anchor ourselves on the pronouncements of Sri Ramana Maharishi, who was one of the greatest sages of India, who left his mortal coil in the last century. For this purpose, we have selected some excerpts from one of the most celebrated works in Ramana literature known as Talks which was put together by Sri Mungala Venkatramiah and subsequently published by Sri Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai. It is a veritable Bible for Ramana devotees and widely regarded as such. The central challenge in all management is realizing the nature of oneself. -

The Humanitarian Initiatives

® THE HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVES OF SRI MATA AMRITANANDAMAYI DEVI (MATA AMRITANANDAMAYI MATH) embracing the world ® is a global network of charitable projects conceived by the Mata Amritanandamayi Math (an NGO with Special Consultative Status to the United Nations) www.embracingtheworld.org © 2003 - 2013 Mata Amritanandamayi Mission Trust, Amritapuri, Kollam, 690525, India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, reproduced, transcribed or translated into any language, in any form, by any means without prior agreement and written permission of the publisher. Edition 12, January 2013 Amma | 06 Disaster Relief | 15 Empowering Women | 34 Building Homes | 38 Community Outreach | 45 Care Homes for Children | 51 Public Health | 56 Education for Everyone | 59 Research for a Better World | 66 Healthcare | 73 Fighting Hunger | 82 Green Initiatives | 85 Amrita Institutions | 88 my religion Contacts | 95 is love Amma The world should know that a life dedicated to selfless love and service is possible. Amma Amma’s Life Amma was born in a remote coastal village in Amma was deeply affected by the profound Each of Embracing the World’s projects has Kerala, South India in 1953. Even as a small suffering she witnessed. According to Hindu- been initiated in response to the needs of girl, she drew attention with the many hours she ism, the suffering of the individual is due to the world’s poor who have come to unburden spent in deep meditation on the seashore. She his or her own karma — the results of actions their hearts to Amma and cry on her shoulder. -

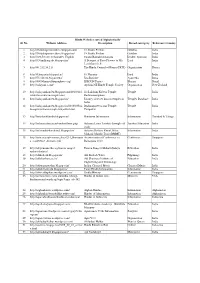

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Indian History Ancient Indian History : General Facts About Indian Rulers and Historical Periods

Indian History Ancient Indian History : General Facts about Indian rulers and historical periods The Mauryan Empire (325 BC -183 BC) Chandragupta Maurya : In 305 BC Chandragupta defeated Seleucus Nikator, who surrendered a vast territory. Megasthenese was a Greek ambassador sent to the court of Chandragupta Maurya by Seleucus Bindusara: Bindusara extended the kingdom further and conquered the south as far as Mysore Asoka : (304– 232 BCE) Facts about Mauryas During Mauryan rule, though there was banking system in India. yet usury was customary and the rate of interest was 15’ /’ per annum on borrowing money. In less secure transactions (like sea Voyages etc) the rate of interest could be as high as 60 per annum. During Mauryan period, the punch marked coins (mostly of silver) were the common units of transactions. Megasthenes in his Indies had mentioned 7 castes in Mauryan society. They were philosophers, farmers, soldiers, herdsmen, artisans, magistrates and councilors. For latest updates : subscribe our Website - www.defenceguru.co.in The Age of the Guptas (320 AD-550 AD) Chandragupta I 320 - 335 AD Samudragupta 335-375 AD Ramagupta 375 - 380 AD Chandragupta Vikramaditya 380-413 AD Kumargupta Mahendraditya 415-455 AD Skandagupta 455-467 AD Later Guptas : Purugupia, Narasimhagupta, Baladitya. Kumargupta II, Buddhagupta, Bhanugupta, Harshagupta, Damodargupta, Mahasenagupta Literature : Authors and Book Bhasa -Svapanavasavdattam Shudrak -Mrichchakatika Amarkosh -Amarsimha Iswara Krishna -Sankhya Karika Vatsyana -Kama Sutra Vishnu (Gupta -Panchatantra Narayan Pandit -Hitopdesha For latest updates : subscribe our Website - www.defenceguru.co.in Bhattin -Ravan Vadha Bhaivi -Kiratarjunyam Dandin -Daskumarachanta Aryabhatta -Aryabhattyan Vishakha Datta -Mudura Rakshasa Indrabhuti -nanassiddhi Varahamihara -Panchasiddh antika, Brihad Samhita Kalidas : Kalidas wrote a number of such excellent dramas like Sakuntala, Malavikagnimitram, Vikrumorvasiyatn, epics like the Raghuvamsa, and lyric poetry like the Ritu-Samhara and the Meghaduta. -

Around the Country with Modi

AROUND THE COUNTRY WITH MODI The Gujarat chief minister’s itinerary since he was declared BJP's prime ministerial candidate BJP prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi at an election rally in Udaipur on Saturday PHOTO: PTI POLITICAL Sept 14: Addresses ex-servicemen at Rewari, his KEY EVENTS RALLIES first rally after being declared PM candidate for BJP Sept 21: Addresses the Indian Sept 25: Attends Karyakarta Mahakumbh in diaspora in Tampa, US, via video- Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh along with L KAdvani conference and MP CM Shivraj Singh Chouhan. According to an Sept 30: Inaugurates Bharat Sept 28: estimate, over 500,000 party workers from every Diamond Bourse's Diamond Hall Addresses BJP’s part of the state attended the function Vikas Rally in at Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla Delhi Complex. Lateraddresses the platinum jubilee celebrations of the International Advertising Association in Mumbai Oct 25: Addresses ‘Vijay Oct 14: Delivers a lecture in the US, Shankhnad Rally ‘ in Jhansi Effective Governance in Oct 27: Addresses rally in Hunkaar in Patna's Democracy: Guj Experience, via Oct 26: Gandhi Maidan despite serial blasts ahead of video-conference Addresses his address Oct 18:Delivers the Nani Palkhivala Janjaati Sept 26: Offers prayers at Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Memorial Lecture in Chennai and Morcha releases Arun Shourie's book Sammelan Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. Also visits the royal family of in Udaipur Travancore at Kowdiar Palace and elderly member of the royal Oct 19: Interacts with students in family, Uthradom Thirunal Marthanda Varma. Gandhinagar. Mukesh Ambani Later he also attends 60th birthday celebrations of Satguru Sri and British Petroleum CEO Bob Mata Amritanandamayi Devi in Amritapuri. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Humanitarian Initiatives

HUMANITARIAN INITIATIVES Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi Mata Amritanandamayi Math OUR VOLUNTEERS ARE HELPING PEOPLE IN NEED ON SIX CONTINENTS. North America AFRICA ASIA NORTH AMERICA SOUTH AMERICA EUROPE AUSTRALIA AMMA HAS DONE MORE WORK THAN MANY GOVERNMENTS HAVE EVER DONE FOR THEIR PEOPLE. HER CONTRIBUTION IS ENORMOUS. - Muhammad Yunus 2006 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate & Founder, Grameen Bank + EMBRACINGTHEWORLD.ORG CONTENTS + TAP A CHAPTER TO OPEN The Founder of Embracing the World 4 Basic Needs: Food & Water 13 Basic Needs: Shelter 20 Basic Needs: Healthcare 26 Basic Needs: Education 37 Basic Needs: Livelihood 43 Emergencies 48 Amrita University 55 Environment 61 AYUDH: Our Youth Wing 65 Self-Reliant Villages 69 A Few of Our Centers Around the World 73 + EMBRACINGTHEWORLD.ORG s long as there is enough strength A to reach out to those who come to me, to place my hand on a crying person’s shoulder, I will continue to embrace people. To lovingly caress them, to console and wipe their tears until the end of this mortal frame—this is my wish. - Amma THE FOUNDER OF EMBRACING THE WORLD ri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi—spiritual leader, S humanitarian and visionary—has served the world-community for decades. Known throughout the world simply as Amma, which means mother in her birth language, she imparts wisdom, strength and inspiration to the people who come to see her. Through her extraordinary acts of love, inner strength and self-sacrifice, Amma has endeared herself to millions and inspired thousands to follow in her path of selfless service. TAP FOR THE STORY OF AMMA’S EARLY SEARCH FOR THE MEANING OF SUFFERING OR FIND IT LATER AT: bit.ly/amma-story As a little girl, Amma witnessed firsthand the stark inequality in the world and wondered about the meaning of suffering. -

Indigenist Mobilization

INDIGENIST MOBILIZATION: ‘IDENTITY’ VERSUS ‘CLASS’ AFTER THE KERALA MODEL OF DEVELOPMENT? LUISA STEUR CEU eTD Collection PHD DISSERTATION DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY (BUDAPEST) 2011 CEU eTD Collection Cover photo: AGMS activist and Paniya workers at Aralam Farm, Kerala ( Luisa Steur, 2006) INDIGENIST MOBILIZATION: ‘IDENTITY’ VERSUS ‘CLASS’ AFTER THE KERALA MODEL OF DEVELOPMENT? by Luisa Steur Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Professor Judit Bodnar Professor Prem Kumar Rajaram Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2011 Statement STATEMENT I hereby state that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Budapest, 2011. CEU eTD Collection Indigenist mobilization: ‘Identity’ versus ‘class’ after the Kerala model of development? i Abstract ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the recent rise of "adivasi" (indigenous/tribal) identity politics in the South Indian state of Kerala. It discusses the complex historical baggage and the political risks attached to the notion of "indigeneity" in Kerala and poses the question why despite its draw- backs, a notion of indigenous belonging came to replace the discourse of class as the primary framework through which adivasi workers now struggle for their rights. The thesis answers this question through an analysis of two inter-linked processes: firstly, the cyclical social movement dynamics of increasing disillusionment with - and distantiation from - the class-based platforms that led earlier struggles for emancipation but could not, once in government, structurally alter existing relations of power. -

Life As Philosophy: an Essay on Sreenarayana Guru's Integrity 10

The Researchers’ - Volume IV, Issue II, 25 July-2018 ISSN : 2455-150382 International Research Journal UGC Journal No. – 64379 Date of Acceptance : 23 March 2018 DOI - 10.21276/tr.2018.4.2.AN10 © Dileep. R Life As Philosophy: An Essay on Sreenarayana Guru’s 10 Integrity Dileep. R, Research Scholar, University of Calicut, Kerala, India. email: [email protected] Abstract This paper tries to place Sreenarayana Guru in the context of Kerala modernity. Guru’s relation with the historical context is complex as the sources of his original thinking were non-modern. He criticised caste system out of his ontological realisation that hierarchies in social world are groundless. His practice on himself, sanyasa is seen as an aesthetic crafting of self, following Michel Foucault’s model. Relationship between his actions and thoughts is analysed by foregrounding the ethico-political relationship with knowledge which was integral to him. It is argued that his allegiance to advaita was accidental, though the context for that accident was provided by colonialism. The in-between nature of Tiyya community into which Guru was born played a key role regarding the efficacy of his political interventions. Guru gained cultural capital by acquiring the standards of tradition. This was dubbed as sanskritaisation by some critics but this paper argues that there was an orientation of moving-down in his deeds and philosophical positions. He wrote Atmopadesa satakam, One Hundred Verses of Self Instruction, as he was aware that instructing advaita to others was absurd. He was not a doctrinaire advaitin. Keywords : Modernity, Sreenarayana, Karuna, Advaita, Asceticism Discourses on saints, sages and other holy men traditionally and commonly take the form “the life and works of ----”. -

Sumi Project

1 CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................ 3-11 Chapter 1 Melting Jati Frontiers ................................................................ 12-25 Chapter 2 Enlightenment in Travancore ................................................... 26-45 Chapter 3 Emergence of Vernacular Press; A Motive Force to Social Changes .......................................... 46-61 Chapter 4 Role of Missionaries and the Growth of Western Education...................................................................... 62-71 Chapter 5 A Comparative Study of the Social Condions of the Kerala in the 19th Century with the Present Scenerio...................... 72-83 Conclusion ............................................................................................ 84-87 Bibliography .......................................................................................88-104 Glossary ............................................................................................105-106 2 3 THE SOCIAL CONDITIONS OF KERALA IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO TRAVANCORE PRINCELY STATE Introduction In the 19th century Kerala was not always what it is today. Kerala society was not based on the priciples of social freedom and equality. Kerala witnessed a cultural and ideological struggle against the hegemony of Brahmins. This struggle was due to structural changes in the society and the consequent emergence of a new class, the educated middle class .Although the upper caste -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore