Body Shape Model, Physical Activity and Eating Behaviour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: an Evolutionary Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Psychological Topics 15 (2006), 2, 331-350 Original Scientific Article – UDC 159.9.015.7.072 572.51-055.2 Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: An Evolutionary Perspective Devendra Singh University of Texas at Austin Department of Psychology Dorian Singh Oxford University Department of Social Policy and Social Work Abstract The main aim of this paper is to present an evolutionary perspective for why women’s attractiveness is assigned a great importance in practically all human societies. We present the data that the woman’s body shape, or hourglass figure as defined by the size of waist-to-hip-ratio (WHR), reliably conveys information about a woman’s age, fertility, and health and that systematic variation in women’s WHR invokes systematic changes in attractiveness judgment by participants both in Western and non-Western societies. We also present evidence that attractiveness judgments based on the size of WHR are not artifact of body weight reduction. Then we present cross-cultural and historical data which attest to the universal appeal of WHR. We conclude that the current trend of describing attractiveness solely on the basis of body weight presents an incomplete, and perhaps inaccurate, picture of women’s attractiveness. “... the buttocks are full but her waist is narrow ... the one for who[m] the sun shines ...” (From the tomb of Nefertari, the favorite wife of Ramses II, second millennium B.C.E.) “... By her magic powers she assumed the form of a beautiful woman .. -

Understanding 7 Understanding Body Composition

PowerPoint ® Lecture Outlines 7 Understanding Body Composition Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Objectives • Define body composition . • Explain why the assessment of body size, shape, and composition is useful. • Explain how to perform assessments of body size, shape, and composition. • Evaluate your personal body weight, size, shape, and composition. • Set goals for a healthy body fat percentage. • Plan for regular monitoring of your body weight, size, shape, and composition. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Body Composition The relative amounts of lean tissue and fat tissue in your body. • Lean Body Mass Your body’s total amount of lean/fat-free tissue (muscles, bones, skin, organs, body fluids). • Fat Mass Body mass made up of fat tissue. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Percent Body Fat The percentage of your total weight that is fat tissue (weight of fat divided by total body weight). • Essential Fat Fat necessary for normal body functioning (including in the brain, muscles, nerves, lungs, heart, and digestive and reproductive systems). • Storage Fat Nonessential fat stored in tissue near the body’s surface. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Why Body Size, Shape, and Composition Matter Knowing body composition can help assess health risks. • More people are now overweight or obese. • Estimates of body composition provide useful information for determining disease risks. Evaluating body size and shape can motivate healthy behavior change. • Changes in body size and shape can be more useful measures of progress than body weight. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition for Men and Women Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Relationship Between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: a Systematic Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Relationship between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: A Systematic Review Cristina Bouzas , Maria del Mar Bibiloni and Josep A. Tur * Research Group on Community Nutrition and Oxidative Stress, University of the Balearic Islands & CIBEROBN (Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition CB12/03/30038), E-07122 Palma de Mallorca, Spain; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (M.d.M.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-971-1731; Fax: +34-971-173184 Received: 21 March 2019; Accepted: 7 May 2019; Published: 9 May 2019 Abstract: Objective: To assess the scientific evidence on the relationship between body image and body weight control in overweight 55-year-old adults. Methods: The literature search was conducted ≥ on MEDLINE database via PubMed, using terms related to body image, weight control and body composition. Inclusion criteria were scientific papers, written in English or Spanish, made on older adults. Exclusion criteria were eating and psychological disorders, low sample size, cancer, severe diseases, physiological disorders other than metabolic syndrome, and bariatric surgery. Results: Fifty-seven studies were included. Only thirteen were conducted exclusively among 55-year-old ≥ adults or performed analysis adjusted by age. Overweight perception was related to spontaneous weight management, which usually concerned dieting and exercising. More men than women showed over-perception of body image. Ethnics showed different satisfaction level with body weight. As age increases, conformism with body shape, as well as expectations concerning body weight decrease. Misperception and dissatisfaction with body weight are risk factors for participating in an unhealthy lifestyle and make it harder to follow a healthier lifestyle. -

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes Karol A Gutowski, MD, FACS Private Practice University of Illinois & University of Chicago Refinements • 360o assessment & treatment • Expanded BMI inclusion • Lipo-abdominoplasty • Low scar • Long scar • Monsplasty • No “dog ears” • No drains • Repurpose the fat • Rapid recovery protocols (ERAS) What I Do and Don’t Do • “Standard” Abdominoplasty is (almost) dead – Does not treat the entire trunk – Fat not properly addressed – Problems with lateral trunk contouring – Do it 1% of cases • Solution: 360o Lipo-Abdominoplasty – Addresses entire trunk and flanks – No Drains & Rapid Recovery Techniques Patient Happy, I’m Not The Problem: Too Many Dog Ears! Thanks RealSelf! Take the Dog (Ear) Out! Patients Are Telling Us What To Do Not enough fat removed Not enough skin removed Patient Concerns • “Ideal candidate” by BMI • Pain • Downtime • Scar – Too high – Too visible – Too long • Unnatural result – Dog ears – Mons aesthetics Solutions • “Ideal candidate” by BMI Extend BMI range • Pain ERAS protocols + NDTT • Downtime ERAS protocols + NDTT • Scar Scar planning – Too high Incision markings – Too visible Scar care – Too long Explain the need • Unnatural result Technique modifications – Dog ears Lipo-abdominoplasty – Mons aesthetics Mons lift Frequent Cause for Reoperation • Lateral trunk fullness – Skin (dog ear), fat, or both • Not addressed with anterior flank liposuction alone – need posterior approach • Need a 360o approach with extended skin excision (Extended Abdominoplasty) • Patient -

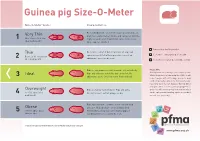

Guinea Pig Size-O-Meter Will 3 Abdominal Curve

Guinea pig Size-O- Meter Size-O-Meter Score: Characteristics: Each individual rib can be felt easily, hips and spine are Very Thin prominent and extremely visible and can be felt with the 1 More than 20% below slightest touch. Under abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Spine appears hunched. Your pet is a healthy weight Thin Each rib is easily felt but not prominent. Hips and spine are easily felt with no pressure. Less of an Seek advice about your pet’s weight Between 10-20% below 2 abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Seek advice as your pet could be at risk Ribs are not prominent and cannot be felt individually. Please note Hips and spine are not visible but can be felt. No Getting hands on is the key to this simple system. Ideal Whilst the pictures in Guinea pig Size-O-Meter will 3 abdominal curve. Chest narrower then hind end. help, it may be difficult to judge your pet’s body condition purely by sight alone. Some guinea pigs have long coats that can disguise ribs, hip bones and spine, while a short coat may highlight these Overweight Ribs are harder to distinguish. Hips and spine areas. You will need to gently feel your pet which 4 10 -15% above ideal difficult to feel. Feet not always visible. can be a pleasurable bonding experience for both body weight you and your guinea pig. Ribs, hips and spine cannot be felt or can with mild Obese pressure. No body shape can be distinguished. -

Know Dieting: Risks and Reasons to Stop

k"#w & ieting, -isks and -easons to 2top Dieting: Any attempts in the name of weight loss, “healthy eating” or body sculpting to deny your body of the essential, well-balanced nutrients and calories it needs to function to its fullest capacity. The Dieting Mindset: When dissatisfaction with your natural body shape or size leads to a decision to actively change your physical body weight or shape. Dieting has become a national pastime, especially for women. ∗ Americans spend more than $40 billion dollars a year on dieting and diet-related products. That’s roughly equivalent to the amount the U.S. Federal Government spends on education each year. ∗ It is estimated that 40-50% of American women are trying to lose weight at any point in time. ∗ One recent study revealed that 91% of women on a college campus had dieted. 22% dieted “often” or “always.” (Kurth et al., 1995). ∗ Researchers estimate that 40-60% of high school girls are on diets (Sardula et al., 1993; Rosen & Gross, 1987). ∗ Another study found that 46% of 9-11 year olds are sometimes or very often on diets (Gustafson-Larson & Terry, 1992). ∗ And, another researcher discovered that 42% of 1st-3rd grade girls surveyed reported wanting to be thinner (Collins, 1991). The Big Deal About Dieting: What You Should Know ∗ Dieting rarely works. 95% of all dieters regain their lost weight and more within 1 to 5 years. ∗ Dieting can be dangerous: ! “Yo-yo” dieting (repetitive cycles of gaining, losing, & regaining weight) has been shown to have negative health effects, including increased risk of heart disease, long-lasting negative impacts on metabolism, etc. -

3D Optical Imaging As a New Tool for the Objective Evaluation of Body Shape Changes After Bariatric Surgery

Obesity Surgery https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04408-4 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS 3D Optical Imaging as a New Tool for the Objective Evaluation of Body Shape Changes After Bariatric Surgery Andreas Kroh1 & Florian Peters2 & Patrick H. Alizai 1 & Sophia Schmitz1 & Frank Hölzle2 & Ulf P. Neumann1,3 & Florian T. Ulmer1,3 & Ali Modabber2 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Introduction Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment option for obesity. It results in massive weight loss and improvement of obesity-related diseases. At the same time, it leads to a drastic change in body shape. These body shape changes are mainly measured by two-dimensional measurement methods, such as hip and waist circumference. These measurement methods suffer from significant measurement errors and poor reproducibility. Here, we present a three- dimensional measurement tool of the torso that can provide an objective and reproducible source for the detection of body shape changes after bariatric surgery. Material and Methods In this study, 25 bariatric patients were scanned with Artec EVA®, an optical three-dimensional mobile scanner up to 1 week before and 6 months after surgery. Data were analyzed, and the volume of the torso, the abdominal circumference and distances between specific anatomical landmarks were calculated. The results of the processed three-dimensional measurements were compared with clinical data concerning weight loss and waist circumference. Results The volume of the torso decreased after bariatric surgery. Loss of volume correlated strongly with weight loss 6 months after the operation (r =0.6425,p = 0.0005). Weight loss and three-dimensional processed data correlated better (r =0.6121,p = 0.0011) than weight loss and waist circumference measured with a measuring tape (r =0.3148,p =0.1254). -

Weight Loss Behavior in Obese Patients Before Seeking Professional Treatment in Taiwan

Obesity Research & Clinical Practice (2009) 3, 35—43 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Weight loss behavior in obese patients before seeking professional treatment in Taiwan Tsan-Hon Liou a,b, Nicole Huang c, Chih-Hsing Wu d, Yiing-Jenq Chou c, Yiing-Mei Liou e, Pesus Chou c,∗ a Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Taipei Medical University-Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan b Graduate Institute of Injury Prevention and Control, College of Public Health and Nutrition, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan c Community Medicine Research Center and Institute of Public Health, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan d Department of Family Medicine, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan e Institute of Community Health Nursing, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan Received 13 March 2008; received in revised form 22 September 2008; accepted 14 October 2008 KEYWORDS Summary Obesity; Objective: To assess weight loss strategies and behaviors in obese patients prior to Anti-obesity drug; seeking professional obesity treatment in Taiwan. Weight expectation; Design: A cross-sectional study was conducted between 1 July 2004 and 30 June Weight loss behavior 2005. Setting and subjects: Obese subjects (1060; 791 females; age, ≥18 years; median BMI, 29.5 kg/m2) seeking treatment in 18 Taiwan clinics specializing in obesity treat- ment were enrolled and completed a self-administered questionnaire. Results: Of the 1060 subjects, the prevalence of anti-obesity drug use was 50.8%; more females than males used anti-obesity drugs (53.6% vs. 42.4%). Approximately one-third of normal weight or overweight subjects with no concomitant obesity- related risk factors took anti-obesity drugs. -

Fit3d Wellness Metrics Glossary Gain a More In-Depth Understanding

Fit3D Wellness Metrics Glossary Gain a more in-depth understanding about each metric. Body Shape Body Shape Rating (BSR) Summary Fit3D extracted SBSI, ABSI, Trunk to Leg Volume Ratio, body fat percentage, and BMI from more than 26,000 scans. Fit3D then evaluated the correlation between each algorithm and calculated the weighted values for the health risk outcomes based on the overall Fit3D user population. This results in a Body Shape Rating (BSR). A user can then understand how their body shape wellness compares with the rest of the Fit3D population. Ways to Improve The primary way to improve your BSR is to increase the density of your body, build the muscle in your legs, and decrease your waist circumference. This can be done through a balanced mix of good nutrition and exercise. Consult with your trainer, nutritionist, coaches, or doctors to set up a plan. References To better understand ABSI, SBSI, Body Fat Percentage and Trunk to Leg Volume Ratio, please refer to the descriptions below or the research from the following links: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0039504 http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0144639 http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0068716 Formula Proprietary ABSI Summary A Body Shape Index (ABSI) is a simple way to evaluate total body shape to avoid health and wellness risks associated with obesity. ABSI is a factor of the roundness of the waist and is associated with Body Mass Index (BMI) and height. The lower this number is, the better. -

Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert

Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio Report of a WHO Expert Consultation GENEVA, 8–11 DECEMBER 2008 Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation Geneva, 8–11 December 2008 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Waist circumference and waist–hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008. 1.Body mass index. 2.Body constitution. 3.Body composition. 4.Obesity. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 150149 1 (NLM classification: QU 100) © World Health Organization 2011 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Children's Views About Obesity, Body Size, Shape and Weight

Children’s views about obesity, body size, shape and weight A systematic review Report written by Rebecca Rees, Kathryn Oliver, Jenny Woodman and James Thomas EPPI-Centre Social Science Research Unit Institute of Education University of London EPPI-Centre report no. 1707 • December 2009 REPORT The authors of this report are: Rebecca Rees (RR), Kathryn Oliver (KO), Jenny Woodman (JW), James Thomas (JT) (EPPI-Centre). Acknowledgements It is important to acknowledge the work of the authors of studies included in this review and the children who participated in them, without which the review would have had no data. Particular thanks also go to Theo Lorenc (TL) and Claire Stansfield (CS), who participated in searching and screening for the review; to members of the Steering Group of the EPPI-Centre’s Health Promotion and Public Health Reviews Facility for their helpful suggestions and material for the review; to the participants in the NCB Young People’s Public Health Group for their work reflecting on the review’s findings; to the NCB’s Louca-Mai Brady and Deepa Pagarani for facilitating workshops with the Group; to Sandy Oliver for commenting on the report; to Angela Harden (AH), Josephine Kavanagh (JK), Ann Oakley (AO) and Helen Roberts (HR) for their input into the protocol; and to Jenny Caird and other members of the Health Promotion and Public Health team for their support and advice. This work was undertaken by the EPPI-Centre, which received funding from the Department of Health (England). The views expressed in the report are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. -

Relationship Between “A Body Shape Index (ABSI)”

Gomez-Peralta et al. Diabetol Metab Syndr (2018) 10:21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0323-8 Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome RESEARCH Open Access Relationship between “a body shape index (ABSI)” and body composition in obese patients with type 2 diabetes Fernando Gomez‑Peralta1*, Cristina Abreu1, Margarita Cruz‑Bravo1, Elvira Alcarria1, Gala Gutierrez‑Buey1, Nir Y. Krakauer2 and Jesse C. Krakauer3 Abstract Background: Obesity is known to be related to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D). The most com‑ monly used anthropometric indicator (body mass index [BMI]) presents several limitations such as the lack of possibil‑ ity to distinguish adipose tissue distribution. Thus, this study examines the suitability of a body shape index (ABSI) for prediction of body composition and sarcopenic obesity in obese or overweight T2D subjects. Methods: Cross-sectional study in 199 overweight/obese T2D adults. Anthropometric (BMI, ABSI) and body composi‑ tion (fat mass [FM], fat-free mass [FFM], fat mass index [FMI] and fat-free mass index, and the ratio FM/FFM as an index of sarcopenic obesity) data was collected, as well as metabolic parameters (glycated haemoglobin [HbA 1c], mean blood glucose, fasting plasma glucose [FPG], high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL], low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides [TG] levels; the ratio TG/HDL was also calculated as a surrogate marker for insulin resistance). Results: ABSI was signifcantly associated with age and waist circumference. It showed a statistically signifcant corre‑ lation with BMI exclusively in women. Regarding body composition, in men, ABSI was associated with FM (%), while in women it was associated with both FM and FFM.