A Body Shape Index (ABSI) - Is It Time to Replace Body Mass Index?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex-And Age-Specific Optimal Anthropometric Indices As

Hindawi International Journal of Endocrinology Volume 2018, Article ID 1067603, 16 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1067603 Research Article Sex- and Age-Specific Optimal Anthropometric Indices as Screening Tools for Metabolic Syndrome in Chinese Adults Jia Zhang , Wenhua Zhu, Lifeng Qiu, Lijuan Huang, and Lizheng Fang Department of General Practice, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China Correspondence should be addressed to Lizheng Fang; [email protected] Received 14 February 2018; Revised 26 August 2018; Accepted 3 September 2018; Published 17 September 2018 Academic Editor: GianLuca Colussi Copyright © 2018 Jia Zhang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Objectives. To compare the predictive ability of six anthropometric indices for identification of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and to determine their optimal cut-off points among Chinese adults. Methods. A total of 59,029 participants were enrolled. Body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), a body shape index (ABSI), body roundness index (BRI), and conicity index (CI) were measured. Receiver-operating characteristic curves analyses were performed to determine the discriminatory power of these indices for the identification of cardiometabolic risks and diagnosis of MetS. The differences in the area under the curve (AUC) values among the indices were evaluated. The Youden index was used to determine the optimal cut-off points. Results. WHtR and BRI exhibited the highest AUC values for identifying MetS and most cardiometabolic risk factors in both sexes, whereas ABSI showed the lowest AUC value. -

Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: an Evolutionary Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Psychological Topics 15 (2006), 2, 331-350 Original Scientific Article – UDC 159.9.015.7.072 572.51-055.2 Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: An Evolutionary Perspective Devendra Singh University of Texas at Austin Department of Psychology Dorian Singh Oxford University Department of Social Policy and Social Work Abstract The main aim of this paper is to present an evolutionary perspective for why women’s attractiveness is assigned a great importance in practically all human societies. We present the data that the woman’s body shape, or hourglass figure as defined by the size of waist-to-hip-ratio (WHR), reliably conveys information about a woman’s age, fertility, and health and that systematic variation in women’s WHR invokes systematic changes in attractiveness judgment by participants both in Western and non-Western societies. We also present evidence that attractiveness judgments based on the size of WHR are not artifact of body weight reduction. Then we present cross-cultural and historical data which attest to the universal appeal of WHR. We conclude that the current trend of describing attractiveness solely on the basis of body weight presents an incomplete, and perhaps inaccurate, picture of women’s attractiveness. “... the buttocks are full but her waist is narrow ... the one for who[m] the sun shines ...” (From the tomb of Nefertari, the favorite wife of Ramses II, second millennium B.C.E.) “... By her magic powers she assumed the form of a beautiful woman .. -

Understanding 7 Understanding Body Composition

PowerPoint ® Lecture Outlines 7 Understanding Body Composition Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Objectives • Define body composition . • Explain why the assessment of body size, shape, and composition is useful. • Explain how to perform assessments of body size, shape, and composition. • Evaluate your personal body weight, size, shape, and composition. • Set goals for a healthy body fat percentage. • Plan for regular monitoring of your body weight, size, shape, and composition. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Body Composition The relative amounts of lean tissue and fat tissue in your body. • Lean Body Mass Your body’s total amount of lean/fat-free tissue (muscles, bones, skin, organs, body fluids). • Fat Mass Body mass made up of fat tissue. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Percent Body Fat The percentage of your total weight that is fat tissue (weight of fat divided by total body weight). • Essential Fat Fat necessary for normal body functioning (including in the brain, muscles, nerves, lungs, heart, and digestive and reproductive systems). • Storage Fat Nonessential fat stored in tissue near the body’s surface. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Why Body Size, Shape, and Composition Matter Knowing body composition can help assess health risks. • More people are now overweight or obese. • Estimates of body composition provide useful information for determining disease risks. Evaluating body size and shape can motivate healthy behavior change. • Changes in body size and shape can be more useful measures of progress than body weight. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition for Men and Women Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Relationship Between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: a Systematic Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Relationship between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: A Systematic Review Cristina Bouzas , Maria del Mar Bibiloni and Josep A. Tur * Research Group on Community Nutrition and Oxidative Stress, University of the Balearic Islands & CIBEROBN (Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition CB12/03/30038), E-07122 Palma de Mallorca, Spain; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (M.d.M.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-971-1731; Fax: +34-971-173184 Received: 21 March 2019; Accepted: 7 May 2019; Published: 9 May 2019 Abstract: Objective: To assess the scientific evidence on the relationship between body image and body weight control in overweight 55-year-old adults. Methods: The literature search was conducted ≥ on MEDLINE database via PubMed, using terms related to body image, weight control and body composition. Inclusion criteria were scientific papers, written in English or Spanish, made on older adults. Exclusion criteria were eating and psychological disorders, low sample size, cancer, severe diseases, physiological disorders other than metabolic syndrome, and bariatric surgery. Results: Fifty-seven studies were included. Only thirteen were conducted exclusively among 55-year-old ≥ adults or performed analysis adjusted by age. Overweight perception was related to spontaneous weight management, which usually concerned dieting and exercising. More men than women showed over-perception of body image. Ethnics showed different satisfaction level with body weight. As age increases, conformism with body shape, as well as expectations concerning body weight decrease. Misperception and dissatisfaction with body weight are risk factors for participating in an unhealthy lifestyle and make it harder to follow a healthier lifestyle. -

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes Karol A Gutowski, MD, FACS Private Practice University of Illinois & University of Chicago Refinements • 360o assessment & treatment • Expanded BMI inclusion • Lipo-abdominoplasty • Low scar • Long scar • Monsplasty • No “dog ears” • No drains • Repurpose the fat • Rapid recovery protocols (ERAS) What I Do and Don’t Do • “Standard” Abdominoplasty is (almost) dead – Does not treat the entire trunk – Fat not properly addressed – Problems with lateral trunk contouring – Do it 1% of cases • Solution: 360o Lipo-Abdominoplasty – Addresses entire trunk and flanks – No Drains & Rapid Recovery Techniques Patient Happy, I’m Not The Problem: Too Many Dog Ears! Thanks RealSelf! Take the Dog (Ear) Out! Patients Are Telling Us What To Do Not enough fat removed Not enough skin removed Patient Concerns • “Ideal candidate” by BMI • Pain • Downtime • Scar – Too high – Too visible – Too long • Unnatural result – Dog ears – Mons aesthetics Solutions • “Ideal candidate” by BMI Extend BMI range • Pain ERAS protocols + NDTT • Downtime ERAS protocols + NDTT • Scar Scar planning – Too high Incision markings – Too visible Scar care – Too long Explain the need • Unnatural result Technique modifications – Dog ears Lipo-abdominoplasty – Mons aesthetics Mons lift Frequent Cause for Reoperation • Lateral trunk fullness – Skin (dog ear), fat, or both • Not addressed with anterior flank liposuction alone – need posterior approach • Need a 360o approach with extended skin excision (Extended Abdominoplasty) • Patient -

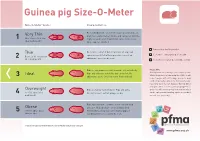

Guinea Pig Size-O-Meter Will 3 Abdominal Curve

Guinea pig Size-O- Meter Size-O-Meter Score: Characteristics: Each individual rib can be felt easily, hips and spine are Very Thin prominent and extremely visible and can be felt with the 1 More than 20% below slightest touch. Under abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Spine appears hunched. Your pet is a healthy weight Thin Each rib is easily felt but not prominent. Hips and spine are easily felt with no pressure. Less of an Seek advice about your pet’s weight Between 10-20% below 2 abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Seek advice as your pet could be at risk Ribs are not prominent and cannot be felt individually. Please note Hips and spine are not visible but can be felt. No Getting hands on is the key to this simple system. Ideal Whilst the pictures in Guinea pig Size-O-Meter will 3 abdominal curve. Chest narrower then hind end. help, it may be difficult to judge your pet’s body condition purely by sight alone. Some guinea pigs have long coats that can disguise ribs, hip bones and spine, while a short coat may highlight these Overweight Ribs are harder to distinguish. Hips and spine areas. You will need to gently feel your pet which 4 10 -15% above ideal difficult to feel. Feet not always visible. can be a pleasurable bonding experience for both body weight you and your guinea pig. Ribs, hips and spine cannot be felt or can with mild Obese pressure. No body shape can be distinguished. -

Article the Association of Food Consumption Scores, Body Shape Index, and Hypertension in a Seven-Year Follow-Up Among Indonesian Adults: a Longitudinal Study

Article The Association of Food Consumption Scores, Body Shape Index, and Hypertension in a Seven-Year Follow-Up among Indonesian Adults: A Longitudinal Study Emyr Reisha Isaura 1, Yang-Ching Chen 1,2 and Shwu-Huey Yang 1,3,* 1 School of Nutrition and Health Sciences, College of Nutrition, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11041, Taiwan; [email protected] (E.R.I.); [email protected] (Y.-C.C.) 2 Department of Family Medicine, Taipei City Hospital, ZhongXing Branch, Taipei 10341, Taiwan 3 Nutrition Research Center, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei 11041, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 13 December 2017; Accepted: 20 January 2018; Published: 22 January 2018 Abstract: Aims: The concept of food security and its association with chronic diseases are both well-established. During the years within the scope of the study, there was a significant increase in the body shape index (ABSI) of Indonesian adults. This study tested the hypothesis that the association between food security and chronic diseases is mediated, in part, by ABSI. Methods: Data was obtained from 2156 Indonesian adults using the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS) in 2007 and 2014. Longitudinal study participants were interviewed face-to-face for dietary intake data using the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Food security, a concept developed by the World Food Programme (WFP), was calculated based on a food consumption score analysis using the FFQ. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) and a Sobel–Goodman test were used to test the hypothesis in this study. Results: The food consumption score was negatively associated with ABSI. It was also negatively associated with systolic blood pressure (p < 0.001). -

Effects of Body Mass Index and a Body Shape Index of Young Healthy

International Journal of Yogic, Human Movement and Sports Sciences 2019; 4(1): 788-793 ISSN: 2456-4419 Impact Factor: (RJIF): 5.18 Yoga 2019; 4(1): 788-793 Effects of body mass index and a body shape index of © 2019 Yoga www.theyogicjournal.com young healthy sedentary men and women Received: 14-11-2018 Accepted: 16-12-2018 Jassim AJ Jassim AJ and Dr. C Jubilet Gnanachellam MPhil Scholar, Physical Education Department, SRM Abstract University, Chennai, It is health that is real wealth and not pieces of gold and silver”. It is important to an individual, a group, Tamil Nadu, India a nation, and indeed the whole world. There are more nations competing in the Olympic Games. The popularity and importance of performance in sports have increased rapidly in the last few decades. The Dr. C Jubilet Gnanachellam increase in popularity and importance is not only due to the fact that performance sports are glamorous Assistant Professor, Physical Education Department, SRM and spectacular to watch. Sports perform multifarious functions for the human society. The popularity of University, Chennai, sports is still increasing at a fast pace and this happy trend is likely to continue in the future also. With all Tamil Nadu, India round advancement in the science of sports new disciplines are emerging with super specializations. The purpose of study was to analyze the effect of body mass index and a body shape index of young healthy sedentary men and women. One thousand (N=1000) sedentary young men and women studying schools and colleges in Kerala state were selected as subject for the study. -

Know Dieting: Risks and Reasons to Stop

k"#w & ieting, -isks and -easons to 2top Dieting: Any attempts in the name of weight loss, “healthy eating” or body sculpting to deny your body of the essential, well-balanced nutrients and calories it needs to function to its fullest capacity. The Dieting Mindset: When dissatisfaction with your natural body shape or size leads to a decision to actively change your physical body weight or shape. Dieting has become a national pastime, especially for women. ∗ Americans spend more than $40 billion dollars a year on dieting and diet-related products. That’s roughly equivalent to the amount the U.S. Federal Government spends on education each year. ∗ It is estimated that 40-50% of American women are trying to lose weight at any point in time. ∗ One recent study revealed that 91% of women on a college campus had dieted. 22% dieted “often” or “always.” (Kurth et al., 1995). ∗ Researchers estimate that 40-60% of high school girls are on diets (Sardula et al., 1993; Rosen & Gross, 1987). ∗ Another study found that 46% of 9-11 year olds are sometimes or very often on diets (Gustafson-Larson & Terry, 1992). ∗ And, another researcher discovered that 42% of 1st-3rd grade girls surveyed reported wanting to be thinner (Collins, 1991). The Big Deal About Dieting: What You Should Know ∗ Dieting rarely works. 95% of all dieters regain their lost weight and more within 1 to 5 years. ∗ Dieting can be dangerous: ! “Yo-yo” dieting (repetitive cycles of gaining, losing, & regaining weight) has been shown to have negative health effects, including increased risk of heart disease, long-lasting negative impacts on metabolism, etc. -

3D Optical Imaging As a New Tool for the Objective Evaluation of Body Shape Changes After Bariatric Surgery

Obesity Surgery https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04408-4 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS 3D Optical Imaging as a New Tool for the Objective Evaluation of Body Shape Changes After Bariatric Surgery Andreas Kroh1 & Florian Peters2 & Patrick H. Alizai 1 & Sophia Schmitz1 & Frank Hölzle2 & Ulf P. Neumann1,3 & Florian T. Ulmer1,3 & Ali Modabber2 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Introduction Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment option for obesity. It results in massive weight loss and improvement of obesity-related diseases. At the same time, it leads to a drastic change in body shape. These body shape changes are mainly measured by two-dimensional measurement methods, such as hip and waist circumference. These measurement methods suffer from significant measurement errors and poor reproducibility. Here, we present a three- dimensional measurement tool of the torso that can provide an objective and reproducible source for the detection of body shape changes after bariatric surgery. Material and Methods In this study, 25 bariatric patients were scanned with Artec EVA®, an optical three-dimensional mobile scanner up to 1 week before and 6 months after surgery. Data were analyzed, and the volume of the torso, the abdominal circumference and distances between specific anatomical landmarks were calculated. The results of the processed three-dimensional measurements were compared with clinical data concerning weight loss and waist circumference. Results The volume of the torso decreased after bariatric surgery. Loss of volume correlated strongly with weight loss 6 months after the operation (r =0.6425,p = 0.0005). Weight loss and three-dimensional processed data correlated better (r =0.6121,p = 0.0011) than weight loss and waist circumference measured with a measuring tape (r =0.3148,p =0.1254). -

Weight Loss Behavior in Obese Patients Before Seeking Professional Treatment in Taiwan

Obesity Research & Clinical Practice (2009) 3, 35—43 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Weight loss behavior in obese patients before seeking professional treatment in Taiwan Tsan-Hon Liou a,b, Nicole Huang c, Chih-Hsing Wu d, Yiing-Jenq Chou c, Yiing-Mei Liou e, Pesus Chou c,∗ a Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Taipei Medical University-Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan b Graduate Institute of Injury Prevention and Control, College of Public Health and Nutrition, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan c Community Medicine Research Center and Institute of Public Health, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan d Department of Family Medicine, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan e Institute of Community Health Nursing, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan Received 13 March 2008; received in revised form 22 September 2008; accepted 14 October 2008 KEYWORDS Summary Obesity; Objective: To assess weight loss strategies and behaviors in obese patients prior to Anti-obesity drug; seeking professional obesity treatment in Taiwan. Weight expectation; Design: A cross-sectional study was conducted between 1 July 2004 and 30 June Weight loss behavior 2005. Setting and subjects: Obese subjects (1060; 791 females; age, ≥18 years; median BMI, 29.5 kg/m2) seeking treatment in 18 Taiwan clinics specializing in obesity treat- ment were enrolled and completed a self-administered questionnaire. Results: Of the 1060 subjects, the prevalence of anti-obesity drug use was 50.8%; more females than males used anti-obesity drugs (53.6% vs. 42.4%). Approximately one-third of normal weight or overweight subjects with no concomitant obesity- related risk factors took anti-obesity drugs. -

The Association Between Z-Score of Log-Transformed a Body Shape Index and Cardiovascular Disease in Korea

Original Article Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Diabetes Metab J 2019;43:675-682 https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2018.0169 pISSN 2233-6079 · eISSN 2233-6087 DIABETES & METABOLISM JOURNAL The Association between Z-Score of Log-Transformed A Body Shape Index and Cardiovascular Disease in Korea Wankyo Chung1,2, Jung Hwan Park3, Hye Soo Chung4, Jae Myung Yu4, Shinje Moon4,5, Dong Sun Kim3 1Department of Public Health Science, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Seoul, 2Institute of Health and Environment, Seoul National University, Seoul, 3Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, 4Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Seoul, 5Department of Internal Medicine, Graduate School, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea Background: In order to overcome the limitations of body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC), the z-score of the log-transformed A Body Shape Index (LBSIZ) has recently been introduced. In this study, we analyzed the relationship between the LBSIZ and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in a Korean representative sample. Methods: Data were collected from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination VI to V. The association between CVD and obesity indices was analyzed using a receiver operating characteristic curve. The cut-off value for the LBSIZ was estimated us- ing the Youden index, and the odds ratio (OR) for CVD was determined via multivariate logistic regression analysis. ORs accord- ing to the LBSIZ value were analyzed using restricted cubic spline regression plots. Results: A total of 31,227 Korean healthy adults were analyzed. Area under the curve (AUC) of LBSIZ against CVD was 0.686 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.671 to 0.702), which was significantly higher than the AUC of BMI (0.583; 95% CI, 0.567 to 0.599) or WC (0.646; 95% CI, 0.631 to 0.661) (P<0.001).