Eating Disorders & Obesity Treatments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: an Evolutionary Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Psychological Topics 15 (2006), 2, 331-350 Original Scientific Article – UDC 159.9.015.7.072 572.51-055.2 Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: An Evolutionary Perspective Devendra Singh University of Texas at Austin Department of Psychology Dorian Singh Oxford University Department of Social Policy and Social Work Abstract The main aim of this paper is to present an evolutionary perspective for why women’s attractiveness is assigned a great importance in practically all human societies. We present the data that the woman’s body shape, or hourglass figure as defined by the size of waist-to-hip-ratio (WHR), reliably conveys information about a woman’s age, fertility, and health and that systematic variation in women’s WHR invokes systematic changes in attractiveness judgment by participants both in Western and non-Western societies. We also present evidence that attractiveness judgments based on the size of WHR are not artifact of body weight reduction. Then we present cross-cultural and historical data which attest to the universal appeal of WHR. We conclude that the current trend of describing attractiveness solely on the basis of body weight presents an incomplete, and perhaps inaccurate, picture of women’s attractiveness. “... the buttocks are full but her waist is narrow ... the one for who[m] the sun shines ...” (From the tomb of Nefertari, the favorite wife of Ramses II, second millennium B.C.E.) “... By her magic powers she assumed the form of a beautiful woman .. -

Size Acceptance and Intuitive Eating Improve Health for Obese, Female Chronic Dieters LINDA BACON, Phd; JUDITH S

RESEARCH Current Research Size Acceptance and Intuitive Eating Improve Health for Obese, Female Chronic Dieters LINDA BACON, PhD; JUDITH S. STERN, ScD; MARTA D. VAN LOAN, PhD; NANCY L. KEIM, PhD come variables, and sustained improvements. Diet group ABSTRACT participants lost weight and showed initial improvement in Objective Examine a model that encourages health at ev- many variables at 1 year; weight was regained and little ery size as opposed to weight loss. The health at every improvement was sustained. size concept supports homeostatic regulation and eating Conclusions The health at every size approach enabled intuitively (ie, in response to internal cues of hunger, participants to maintain long-term behavior change; the satiety, and appetite). diet approach did not. Encouraging size acceptance, re- Design Six-month, randomized clinical trial; 2-year follow- duction in dieting behavior, and heightened awareness up. and response to body signals resulted in improved health Subjects White, obese, female chronic dieters, aged 30 to ϭ risk indicators for obese women. 45 years (N 78). J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:929-936. Setting Free-living, general community. Interventions Six months of weekly group intervention (health at every size program or diet program), followed oncern regarding obesity continues to mount among by 6 months of monthly aftercare group support. government officials, health professionals, and the Main outcome measures Anthropometry (weight, body mass Cgeneral public. Obesity is associated with physical index), metabolic fitness (blood pressure, blood lipids), en- health problems, and this fact is cited as the primary ergy expenditure, eating behavior (restraint, eating disor- reason for the public health recommendations encourag- der pathology), and psychology (self-esteem, depression, ing weight loss (1). -

Understanding 7 Understanding Body Composition

PowerPoint ® Lecture Outlines 7 Understanding Body Composition Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Objectives • Define body composition . • Explain why the assessment of body size, shape, and composition is useful. • Explain how to perform assessments of body size, shape, and composition. • Evaluate your personal body weight, size, shape, and composition. • Set goals for a healthy body fat percentage. • Plan for regular monitoring of your body weight, size, shape, and composition. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Body Composition The relative amounts of lean tissue and fat tissue in your body. • Lean Body Mass Your body’s total amount of lean/fat-free tissue (muscles, bones, skin, organs, body fluids). • Fat Mass Body mass made up of fat tissue. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Percent Body Fat The percentage of your total weight that is fat tissue (weight of fat divided by total body weight). • Essential Fat Fat necessary for normal body functioning (including in the brain, muscles, nerves, lungs, heart, and digestive and reproductive systems). • Storage Fat Nonessential fat stored in tissue near the body’s surface. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Why Body Size, Shape, and Composition Matter Knowing body composition can help assess health risks. • More people are now overweight or obese. • Estimates of body composition provide useful information for determining disease risks. Evaluating body size and shape can motivate healthy behavior change. • Changes in body size and shape can be more useful measures of progress than body weight. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition for Men and Women Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. -

I UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO the Weight of Medical

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO The Weight of Medical Authority: The Making and Unmaking of Knowledge in the Obesity Epidemic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology (Science Studies) by Julia Rogers Committee in charge: Professor Martha Lampland, Chair Professor Cathy Gere Professor Isaac Martin Professor David Serlin Professor Charles Thorpe 2018 i Copyright Julia Ellen Rogers, 2018 All Rights Reserved ii The Dissertation of Julia Ellen Rogers is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii DEDICATION For Eric and Anderson iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication ............................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... v List of Figures and Tables ....................................................................................................... xi Vita ....................................................................................................................................... -

Relationship Between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: a Systematic Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Relationship between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: A Systematic Review Cristina Bouzas , Maria del Mar Bibiloni and Josep A. Tur * Research Group on Community Nutrition and Oxidative Stress, University of the Balearic Islands & CIBEROBN (Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition CB12/03/30038), E-07122 Palma de Mallorca, Spain; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (M.d.M.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-971-1731; Fax: +34-971-173184 Received: 21 March 2019; Accepted: 7 May 2019; Published: 9 May 2019 Abstract: Objective: To assess the scientific evidence on the relationship between body image and body weight control in overweight 55-year-old adults. Methods: The literature search was conducted ≥ on MEDLINE database via PubMed, using terms related to body image, weight control and body composition. Inclusion criteria were scientific papers, written in English or Spanish, made on older adults. Exclusion criteria were eating and psychological disorders, low sample size, cancer, severe diseases, physiological disorders other than metabolic syndrome, and bariatric surgery. Results: Fifty-seven studies were included. Only thirteen were conducted exclusively among 55-year-old ≥ adults or performed analysis adjusted by age. Overweight perception was related to spontaneous weight management, which usually concerned dieting and exercising. More men than women showed over-perception of body image. Ethnics showed different satisfaction level with body weight. As age increases, conformism with body shape, as well as expectations concerning body weight decrease. Misperception and dissatisfaction with body weight are risk factors for participating in an unhealthy lifestyle and make it harder to follow a healthier lifestyle. -

Overweight and Obesity in Adults

UWS Clinics Conservative Care Pathways Adopted 10/05 Revised 4/15 OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY IN ADULTS Primary author: Jim Gerber MS, DC Additional contributions made by: Ron LeFebvre DC, Joel Agresta PT, DC Owen T. Lynch DC Edited by: Ron LeFebvre DC Reviewed and Adopted by CSPE Working Group (2014) Amanda Armington DC, Daniel DeLapp DC, DABCO, LAc, ND, Lorraine Ginter DC, Shawn Hatch DC, Ronald LeFebvre DC, Owen T. Lynch DC, Ryan Ondick DC, Joseph Pfeifer DC, Anita Roberts DC, James Strange DC, Laurel Yancey DC Clinical Standards, Protocols, and Education (CSPE) Committee (2005) Shireesh Bhalerao, DC; Daniel DeLapp, DC, DABCO, ND, LAc; Elizabeth Dunlop, DC; Lorraine Ginter, DC; Sean Herrin, DC; Ronald LeFebvre, DC; Owen T. Lynch, DC; Karen E. Petzing, DC; Ravid Raphael, DC, DABCO; Anita Roberts, DC; Steven Taliaferro, DC . UWS care pathways and protocols provide evidence-informed, consensus-based guidelines to support clinical decision making. To best meet a patient's healthcare needs, variation from these guidelines may be appropriate based on more current information, clinical judgment of the practitioner, and/or patient preferences. These pathways and protocols are informed by currently available evidence and developed by UWS personnel to guide clinical education and practice. Although individual procedures and decision points within the pathway may have established validity and/or reliability, the pathway as a whole has not been rigorously tested and therefore should not be adopted wholesale for broader use. Copyright 2015 University -

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes Karol A Gutowski, MD, FACS Private Practice University of Illinois & University of Chicago Refinements • 360o assessment & treatment • Expanded BMI inclusion • Lipo-abdominoplasty • Low scar • Long scar • Monsplasty • No “dog ears” • No drains • Repurpose the fat • Rapid recovery protocols (ERAS) What I Do and Don’t Do • “Standard” Abdominoplasty is (almost) dead – Does not treat the entire trunk – Fat not properly addressed – Problems with lateral trunk contouring – Do it 1% of cases • Solution: 360o Lipo-Abdominoplasty – Addresses entire trunk and flanks – No Drains & Rapid Recovery Techniques Patient Happy, I’m Not The Problem: Too Many Dog Ears! Thanks RealSelf! Take the Dog (Ear) Out! Patients Are Telling Us What To Do Not enough fat removed Not enough skin removed Patient Concerns • “Ideal candidate” by BMI • Pain • Downtime • Scar – Too high – Too visible – Too long • Unnatural result – Dog ears – Mons aesthetics Solutions • “Ideal candidate” by BMI Extend BMI range • Pain ERAS protocols + NDTT • Downtime ERAS protocols + NDTT • Scar Scar planning – Too high Incision markings – Too visible Scar care – Too long Explain the need • Unnatural result Technique modifications – Dog ears Lipo-abdominoplasty – Mons aesthetics Mons lift Frequent Cause for Reoperation • Lateral trunk fullness – Skin (dog ear), fat, or both • Not addressed with anterior flank liposuction alone – need posterior approach • Need a 360o approach with extended skin excision (Extended Abdominoplasty) • Patient -

23 Exercise in Obesity from the Perspective of Hedonic Theory a Call for Sweeping Change in Professional Practice Norms

Panteleimon Ekkekakis et al. Exercise in Obesity Ekkekakis, P., Zenko, Z., & Werstein, K.M. (2018). Exercise in obesity from the perspective of hedonic theory: A call for sweeping change in professional practice norms. In S. Razon & M.L. Sachs (Eds.), Applied exercise psychology: The challenging journey from motivation to adherence (pp. 289-315). New York: Routledge. 23 Exercise in Obesity From the Perspective of Hedonic Theory A Call for Sweeping Change in Professional Practice Norms Panteleimon Ekkekakis , Zachary Zenko , and Kira M . Werstein Two thirds of American adults, as well as the majority of adults in most other western coun- tries, are considered overweight, and up to one third are obese ( Finucane et al., 2011 ; Flegal, Carroll, Kit, & Ogden, 2012 ; Ng et al., 2014 ; von Ruesten et al., 2011 ). The average client that exercise practitioners are likely to face in the United States today has a body mass index of 28.7 kg/m 2 , just short of the threshold for being designated “obese.” In some clinical settings, such as cardiac rehabilitation ( Bader, Maguire, Spahn, O’Malley, & Balady, 2001 ) or osteoarthritis clinics ( Frieden, Jaffe, Stephens, Thacker, & Zaza, 2011 ), half of the patients are classifi ed as obese and almost all are overweight. Regular physical activity is an essential component of lifestyle interventions recommended for weight management ( Jensen et al., 2014 ), having been shown to signifi cantly improve long- term weight loss beyond what can be achieved by diet-only programs ( Johns, Hartmann-Boyce, Jebb, & Aveyard, 2014 ). The problem is that very few adults with obesity participate in physi- cal activity at the recommended levels ( Ekkekakis, Vazou, Bixby, & Georgiadis, 2016 ). -

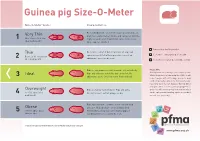

Guinea Pig Size-O-Meter Will 3 Abdominal Curve

Guinea pig Size-O- Meter Size-O-Meter Score: Characteristics: Each individual rib can be felt easily, hips and spine are Very Thin prominent and extremely visible and can be felt with the 1 More than 20% below slightest touch. Under abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Spine appears hunched. Your pet is a healthy weight Thin Each rib is easily felt but not prominent. Hips and spine are easily felt with no pressure. Less of an Seek advice about your pet’s weight Between 10-20% below 2 abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Seek advice as your pet could be at risk Ribs are not prominent and cannot be felt individually. Please note Hips and spine are not visible but can be felt. No Getting hands on is the key to this simple system. Ideal Whilst the pictures in Guinea pig Size-O-Meter will 3 abdominal curve. Chest narrower then hind end. help, it may be difficult to judge your pet’s body condition purely by sight alone. Some guinea pigs have long coats that can disguise ribs, hip bones and spine, while a short coat may highlight these Overweight Ribs are harder to distinguish. Hips and spine areas. You will need to gently feel your pet which 4 10 -15% above ideal difficult to feel. Feet not always visible. can be a pleasurable bonding experience for both body weight you and your guinea pig. Ribs, hips and spine cannot be felt or can with mild Obese pressure. No body shape can be distinguished. -

Know Dieting: Risks and Reasons to Stop

k"#w & ieting, -isks and -easons to 2top Dieting: Any attempts in the name of weight loss, “healthy eating” or body sculpting to deny your body of the essential, well-balanced nutrients and calories it needs to function to its fullest capacity. The Dieting Mindset: When dissatisfaction with your natural body shape or size leads to a decision to actively change your physical body weight or shape. Dieting has become a national pastime, especially for women. ∗ Americans spend more than $40 billion dollars a year on dieting and diet-related products. That’s roughly equivalent to the amount the U.S. Federal Government spends on education each year. ∗ It is estimated that 40-50% of American women are trying to lose weight at any point in time. ∗ One recent study revealed that 91% of women on a college campus had dieted. 22% dieted “often” or “always.” (Kurth et al., 1995). ∗ Researchers estimate that 40-60% of high school girls are on diets (Sardula et al., 1993; Rosen & Gross, 1987). ∗ Another study found that 46% of 9-11 year olds are sometimes or very often on diets (Gustafson-Larson & Terry, 1992). ∗ And, another researcher discovered that 42% of 1st-3rd grade girls surveyed reported wanting to be thinner (Collins, 1991). The Big Deal About Dieting: What You Should Know ∗ Dieting rarely works. 95% of all dieters regain their lost weight and more within 1 to 5 years. ∗ Dieting can be dangerous: ! “Yo-yo” dieting (repetitive cycles of gaining, losing, & regaining weight) has been shown to have negative health effects, including increased risk of heart disease, long-lasting negative impacts on metabolism, etc. -

Rhode Island M Edical J Ournal

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL SPECIAL SECTION OBESITY TREATMENT OPTIONS – AN OVERVIEW GUEST EDITOR: DIETER POHL, MD, FACS MARCH 2017 VOLUME 100 • NUMBER 3 ISSN 2327-2228 RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 14 Medical, Surgical, Behavioral, Preventive Approaches to Address the Obesity Epidemic DIETER POHL, MD, FACS D. Pohl, MD 15 Diabetes, Obesity, and Other Medical Diseases – Is Surgery the Answer? DIETER POHL, MD, FACS, FASMBS AARON BLOOMENTHAL, MD, FACS A. Bloomenthal, MD 18 Obesity Epidemic: Cover photos © Obesity Pharmaceutical weight loss Action Coalition. STEPHANIE A. CURRY, MD S. Curry, MD 21 Behavioral Approaches to the Treatment of Obesity KAYLONI OLSON, MA DALE BOND, PhD RENA R. WING, PhD K. Olson, MD D. Bond, MD R. Wing, PhD 25 More than an Ounce of Prevention: A Medical-Public Health Framework for Addressing Unhealthy Weight in Rhode Island DORA M. DUMONT, PhD, MPH KRISTI A. PAIVA, MPH K. Paiva, MPH E. Lawson, MPH ELIZA LAWSON, MPH 28 Quality Improvement Processes in Obesity Surgery Lead to Higher Quality and Value, Lower Costs HOLLI BROUSSEAU, AGACNP DIETER POHL, MD, FACS, FASMBS H. Brousseau, AGACNP OBESITY TREATMENT OPTIONS – AN OVERVIEW Medical, Surgical, Behavioral, Preventive Approaches to Address the Obesity Epidemic DIETER POHL, MD GUEST EDITOR 14 14 EN This issue of the Rhode Island Medical Journal deals with There are a number of sci- obesity and is meant for the practicing physician to get an entifically well-researched and In Rhode Island, up-to-date overview of available preventative community successful treatment options about 25%, or services from the State of Rhode Island and evidenced-based available. -

A Systematic Review to Answer the Following Question: What Is the Relationship Between the Frequency of Eating During Pregnancy and Gestational Weight Gain?

DRAFT – Current as of 1/21/2020 WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FREQUENCY OF EATING DURING PREGNANCY AND GESTATIONAL WEIGHT GAIN?: SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROTOCOL This document describes the protocol for a systematic review to answer the following question: What is the relationship between the frequency of eating during pregnancy and gestational weight gain? This systematic review is being conducted by the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, Frequency of Eating Subcommittee, and staff from USDA’s Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR). NESR methodology for answering a systematic review question involves: • searching for and selecting articles, • extracting data and assessing the risk of bias of results from each included article, • synthesizing the evidence, • developing a conclusion statement, • grading the evidence underlying the conclusion statement, and • recommending future research. More information about NESR’s systematic review methodology is available on the NESR website: https://nesr.usda.gov/2020-dietary-guidelines-advisory-committee-systematic-reviews. This document includes details about the methodology as it will be applied to the systematic review as follows: • The analytic framework (p. 3) illustrates the overall scope of the question, including the population, the interventions and/or exposures, comparators, and outcomes of interest. • The literature search and screening plan (p. 4) details the electronic databases and inclusion and exclusion criteria (p. 4) that will be used to search for, screen, and select articles to be included in the systematic review. • The literature search and screening results (p. 8) includes a list of included articles, and a list of excluded articles with the rationale for exclusion. This protocol is up-to-date as of: 1/21/2020.