Veiling in Early Modern Europe by Susanna Burghartz (Translated by Jane Caplan)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; to Include the Property of a Lady

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; To Include The Property Of A Lady, Eaton Square, London ( 24 Mar 2021 B) Wed, 24th Mar 2021 Lot 213 Estimate: £100 - £200 + Fees A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES to include a 1930s rose gold organza with a gold jacquard embroidery evening dress, with a square neckline, gold jacquard and green chiffon straps, a v back neckline, a A-line skirt and a gold jacquard and green chiffon sash decorates the back of the dress (74 cm bust, 74 cm waist, 146 cm from shoulder to hem); a 1930s ivory lace sleeveless evening dress, with a v neckline, lace straps and buttons covered in lace are used as zipper on the back, a full skirt and a silk slip (65 cm bust, 61 cm waist, 145 cm from shoulder to hem), the evening dress comes with a matching ivory lace shrug; an 1960s ivory silk wedding dress, with a jewel neckline embellished with white lace, long sleeves, buttons covered in silk are used as zipper on the back, a skirt with white lace hem and a cathedral train (83 cm bust, 83 cm waist, 132 cm from shoulder to front hem), the wedding dress comes with a bridal flower crown with tulle veil; a 1940s ivory silk evening dress, with a square neckline embellished with ivory lace and net, beads and a beige flower applique, short sleeves embellished with taupe net, beads and ivory lace, a skirt with a chapel train and a silk slip (63 cm bust, 58 cm waist, 165 cm from shoulder to front hem), a 1960s baby blue tullle evening dress, with a sweetheart neckline with spaghetti straps and a full skirt made up of layers of tulle and silk, with original label 'Salon Moderne. -

1St Corinthians 11 & the Christian Use of Headcoverings

CCCoooveredveredvered GGlloryory Glory __________________________________________________ ST 1 CORINTHIANS 11 & THE CHRISTIAN USE OF HEADCOVERINGS ________________________ DAVID PHILLIPS Available Online At bitly.com/CoveredGlory Revision 04.15.16 CCOVEREDOVERED GGLORYLORY 1ST CORINTHIANS 11 & THE CHRISTIAN USE OF HEADCOVERINGS CONTENTS PREFACE INTRODUCTION 1. HEADCOVERINGS IN SCRIPTURE . 1 2. WHAT IS THE “HEADCOVERING”? . 3 3. NATURAL HAIR LENGTH: CULTURAL OR UNIVERSAL? . 9 ST 4. HEADCOVERINGS IN 1 CENTURY CULTURE . 10 5. SCRIPTURE'S REASONS FOR THE HEADCOVERING . 11 6. CHRISTIAN HEADCOVERINGS FOR TODAY? . 22 A. APPENDIX: HEADCOVERING THROUGHOUT CHRISTIAN HISTORY . 35 B. APPENDIX: KEY TERMS & PHRASES . 36 ST C. APPENDIX: FURTHER DETAILS ON 1 CENTURY CULTURE . 48 COPYRIGHT 2011-2015 PERMISSION FOR COPYING IS FREELY PROVIDED UNDER THE “CREATIVE COMMONS / ATTRIBUTION 3.0 LICENSE” All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New American Standard Bible® (NASB). Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation (www.lockman.org) Used by permission. Scripture identified as “NIV” is taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. Covered Glory iii Ω PREFACE The Apostle Paul: “I want you to understand that Christ is the head of every man, and the man is the head of a woman, and God is the head of Christ. Every man who has something on his head while praying or prophesying disgraces his head. But every woman who has her head uncovered while praying or prophesying disgraces her head... For a man ought not to have his head covered, since he is the image and glory of God; but the woman is the glory of man.. -

2020 Appendixes

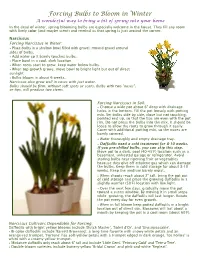

Forcing Bulbs to Bloom in Winter A wonderful way to bring a bit of spring into your home In the dead of winter, spring blooming bulbs are especially welcome in the house. They fill any room with lively color (and maybe scent) and remind us that spring is just around the corner. Narcissus Forcing Narcissus in Water: • Place bulbs in a shallow bowl filled with gravel; mound gravel around sides of bulbs. • Add water so it barely touches bulbs. • Place bowl in a cool, dark location. • When roots start to grow, keep water below bulbs. • When top growth grows, move bowl to bright light but out of direct sunlight. • Bulbs bloom in about 6 weeks. Narcissus also grow well in vases with just water. Bulbs should be firm, without soft spots or scars. Bulbs with two "noses", or tips, will produce two stems. Forcing Narcissus in Soil: • Choose a wide pot about 6” deep with drainage holes in the bottom. Fill the pot loosely with potting mix. Set bulbs side by side, close but not touching, pointed end up, so that the tips are even with the pot rim. Do not press the bulbs into the mix. It should be loose to allow the roots to grow through it easily. Cover with additional potting mix, so the noses are barely covered. • Water thoroughly and empty drainage tray. • Daffodils need a cold treatment for 8-10 weeks. If you pre-chilled bulbs, you can skip this step. Move pot to a dark, cool (40-45°F) location such as a basement, unheated garage or refrigerator. -

Littleton Bible Chapel Position Paper Covering and Uncovering of The

Littleton Bible Chapel Position Paper Covering and Uncovering of the Head during Prayer and Ministry of the Word 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 It has been the practice of LBC for the past forty-five years to ask women to cover their heads when they pray and teach publicly, and for men to uncover their heads when they pray and teach in a public setting. This practice is not an empty tradition of our church but a direct injunction of the Scriptures. We have prepared the following paper on 1 Corinthians 11:2-16, for you to consider the accuracy and the truthfulness of our practice. It is our desire to encourage believers to take this passage seriously and to consistently practice the teaching therein. This has been a long neglected passage, and today is completely unacceptable in our feminist environment. We understand the offense of this teaching. But since we take the passage at face value and not as cultural, we have no choice but to practice its teaching. Our desire as elders is to make people aware of what the Bible teaches about this distinctive Christian practice and to encourage both men and women to practice this teaching. If however, people disagree with our interpretation, we do not force this practice on anyone. We respect the liberty of the conscience of all our fellow believers. 1 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 Headship and Subordination Symbolized by Covering and Uncovering of the Head The letter of 1 Corinthians deals with many practical local church issues and problems, ones that affect all churches in all ages. -

Make Your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…

Make your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…. 1355 W 20 th Avenue Oshkosh, WI 54902 Phone: 920-966-1300 Friday and Sunday Bridal Package 2014 The following services and amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $600 deposit - $400 for banquet facility rental and $200 applied towards food and beverage Saturday Bridal Package 2014 The Following Services and Amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $1,000 deposit - $700 for banquet facility rental and $300 applied towards food and beverage $5,000 Food Minimum DINNER PLATED DINNER ENTREES POULTRY Chicken Forestiere 19.99 Chicken Piccata 19.99 6oz. -

The Vasa Star

THETHE VASA VASA STAR STAR VasastjärnanVasastjärnan PublicationPublication of of THE THE VASA VASA ORDER ORDER OF OF AMERICA AMERICA JULY-AUGUSTJULY-AUGUST 2010 2010 www.vasaorder.comwww.vasaorder.com MEB-E Art Björkner MEB-W Ed Netzel MEB-M Sten Hult MEB-S Ulf Alderlöf MEB-C Ken Banks VGS Gail Olson GS Joan Graham VGM Tore Kellgren GM Bill Lundquist GT Keith Hanlon The Grand Master’s Message Bill Lundquist Dear Vasa Brothers and Sisters, they were when we were founded in 1896, promoting our cul- I humbly and proudly accept the most prestigious office as tural heritage and providing a program of social fellowship. Grand Master of the Vasa Order and thank you for graciously We have suffered losses by death but many from lack of inter- electing me. I assume this office with excitement and much est. I plan to put programs in place to give you ideas to help enthusiasm but well aware of the challenges ahead. I am keep your current members interested and active as well as grateful and truly appreciative of your confidence in my ability make more interesting to potential members. New members to lead the Order for the next four years. I pledge to you that I bring in new enthusiasm, new ideas and new workers. will do my utmost to fulfill the goals I have set for this term. Scandinavians are no strangers to challenges. One such These include but are not limited to goals in the following challenge for all of us over the next four years is the reduced areas: Improvement in transparency between the Grand Lodge budget to The Vasa Star. -

Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine Egypt. Jack M

Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine Egypt. Jack M. Ogden ABSTRACT This study deals with the gold jewellery made and worn in Egypt during the millennium between Alexander the Great's invasion of Egypt and the Arab conquest. Funerary jewellery is largely ignored as are ornaments in the traditional, older Egyptian styles. The work draws upon a wide variety of evidence, in particular the style, composition and construction of surviving jewellery, the many repre- sentations of jewellery in wear, such as funerary portraits, and the numerous literary references from the papyri and from Classical and early Christian writers. Egypt, during the period considered, has provided a greater wealth of such information than anywhere else in the ancient or medieval world and this allows a broadly based study of jewellery in a single ancient society. The individual chapters deal with a brief historical background; the information available from papyri and other literary sources; the sources, distribution, composition and value of gold; the origins and use of mineral and organic gem materials; the economic and social organisation of the goldsmiths' trade; and the individual jewellery types, their chronology, manufacture and significance. This last section is covered in four chapters which deal respectively with rings, earrings, necklets and pendants, and bracelets and armiets. These nine chapters are followed by a detailed bibliography and a list of the 511 illustrations. Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine Egypt. In two volumes Volume 1 - Text. Jack M. Ogden Ph.D. Thesis Universtity of Durham, Department of Oriental Studies. © 1990 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. -

Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Grimoire University Publications Spring 2005 Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005" (2005). Grimoire. 14. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grimoire by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. spring 2005 volume 4 4 fetter from the editress “Staring at the blank page before you, Open up the dirty window, Let the sun illuminate the words that you could not find...” Each time the lyrics of Natasha Bedingfield’s “Unwritten” play over in my head, I can’t help but be reminded of the seemingly unattainable goals I dream up for myself every day. Not just the dream, but also the struggle to make those visions real— to voice the words and feelings that no one else can— quickly becomes more tiring and frustrating than life itself. Compared to the size of the whole, the simple goal of being published in this unknown, student-run maga zine is but a small accomplishment. This becomes obvious, as this book may eventually (and most likely will) pass from your hand, the reader’s, to the ground, or a trashcan, or— if we’re lucky— tossed out of a third-story dorm window. But the Grimoire is more than just a magazine— it’s a monument on which is carved the legacy of hundreds of students. -

MEDIA KIT 2017/18 Welcome to the Inner Circle of DWP

MEDIA KIT 2017/18 Welcome to the inner circle of DWP There is no better way to reflect on the year passing us by and celebrate the start of a new one, quite like the kick-off of an impossible-to-resist portal to all things luxe and beautiful. The launch of the DWP - Insider editorial portfolio is exactly that. I find myself diving into the fascinating dynamics of two luxury industries, that rake in billions of dollars a year- weddings and travel. If you've found yourself staring down the barrel of done- and-dusted wedding trends, filled with nothing but aspirations to be innovative and different, then we've got your back. We have worked hard to create a platform that hand-picks the best in the business, scouting the most coveted frontrunners to become a ‘go-to’ journal for not only the bride and groom, but the entire bridal squad and all high-life aficionados. This inevitable next step in the Destination Wedding Planner Congress journey, takes an in- depth approach to the glamorous side of the luxury wedding industry - the elite ceremonies, the opulent jewelry and couture, and that of lavish destinations and their unique décor, food and wellness offerings. With each digital post and each bi-annual issue, we reveal the jewels in this season’s bridal crown– all perfectly bound in a must-have journal, that aims to connect partners and advertisers with select clientele; and enrich the reader culturally. Aishwarya Tyagi Editor, Destination Wedding Planner- Insider [email protected] The Reader Wedding Planners Wedding budgets and Brides-to-be ranging from from 65+ countries. -

U.S. Customs Service

U.S. Customs Service General Notices DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS, Washington, DC, April 3, 2002. The following documents of the United States Customs Service, Office of Regulations and Rulings, have been determined to be of suffiĆ cient interest to the public and U.S. Customs Service field offices to merit publication in the CUSTOMS BULLETIN. JOHN DURANT, (for Douglas M. Browning, Acting Assistant Commissioner, Office of Regulations and Rulings.) PROPOSED REVOCATION OF RULING LETTER AND REVOCATION OF TREATMENT RELATING TO TARIFF CLASSIFICATION OF COMPONENTS FOR ELECTRICAL TRANSFORMER CORES AGENCY: U.S. Customs Service, Department of the Treasury. ACTION: Notice of proposed revocation of ruling letter and revocation of treatment relating to tariff classification of components for electrical transformer cores. SUMMARY: Pursuant to section 625(c), Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1625(c)), as amended by section 623 of Title VI (Customs ModernizaĆ tion) of the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act (Pub. L. 103ć182, 107 Stat. 2057), this notice advises interested parĆ ties that Customs intends to revoke a ruling relating to the classificaĆ tion, under the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS), of components for electrical transformer cores, and to revoke any treatment Customs has previously accorded to substantially identiĆ cal transactions. These articles are individual pieces of alloy steel, cut to specific sizes and shapes, for use as components of cores for electrical transformers. Customs invites comments on the correctness of the proĆ posed action. DATE: Comments must be received on or before May 17, 2002. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

The Heritage of Dress

Purchased by the AVary Stuart Boor Fund Founded A.D. 1893 Cooper Union Library^ THE HERITAGE OF DRESS PLATE I. Frontispiec Very early man in Java. {See page 5.) THE HERITAGE OF DRESS BEING NOTES ON THE HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF CLOTHES BY WILFRED MARK WEBB FELLOW OF THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON GKNERAL SECRETARY OF THE SELBORNE SOCIETY EDITOR OF " KNOWLEDGE " WITH TWELVE PLATES AND ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-NINE FIGURES IN THE TEXT NEW AND REVISED EDITION LONDON Zbc Uimes :Booft Club 1912 TO HIS WIFE HILDA E. WEBB AS A SMALL TOKEN OF AFFECTION THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY THE WRITER 20IOST PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION HTHE HERITAGE OF DRESS having been out of print for some time, the writer has taken the opportunity afforded him of issuing a second edition, and at the same time of making certain alterations in and additions to the text. Through the efforts of the present publishers the book has been produced in a compacter and handier form without curtailing it in any way, while the price has been halved ; a fact which should tend to carry the volume into those " quiet places " where Ruskin tells us science only lives " with odd people, mostly poor," WILFRED MARK WEBB. Odstock, Hanwell, April, 1912. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION TT would be difficult to find a subject of""more universal ^ interest than that of dress, and hosts of books have been written which deal \vT.th the attire that has been adopted at different times and by various nations or social classes.