Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; to Include the Property of a Lady

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; To Include The Property Of A Lady, Eaton Square, London ( 24 Mar 2021 B) Wed, 24th Mar 2021 Lot 213 Estimate: £100 - £200 + Fees A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES to include a 1930s rose gold organza with a gold jacquard embroidery evening dress, with a square neckline, gold jacquard and green chiffon straps, a v back neckline, a A-line skirt and a gold jacquard and green chiffon sash decorates the back of the dress (74 cm bust, 74 cm waist, 146 cm from shoulder to hem); a 1930s ivory lace sleeveless evening dress, with a v neckline, lace straps and buttons covered in lace are used as zipper on the back, a full skirt and a silk slip (65 cm bust, 61 cm waist, 145 cm from shoulder to hem), the evening dress comes with a matching ivory lace shrug; an 1960s ivory silk wedding dress, with a jewel neckline embellished with white lace, long sleeves, buttons covered in silk are used as zipper on the back, a skirt with white lace hem and a cathedral train (83 cm bust, 83 cm waist, 132 cm from shoulder to front hem), the wedding dress comes with a bridal flower crown with tulle veil; a 1940s ivory silk evening dress, with a square neckline embellished with ivory lace and net, beads and a beige flower applique, short sleeves embellished with taupe net, beads and ivory lace, a skirt with a chapel train and a silk slip (63 cm bust, 58 cm waist, 165 cm from shoulder to front hem), a 1960s baby blue tullle evening dress, with a sweetheart neckline with spaghetti straps and a full skirt made up of layers of tulle and silk, with original label 'Salon Moderne. -

2020 Appendixes

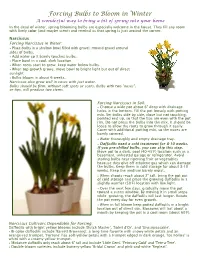

Forcing Bulbs to Bloom in Winter A wonderful way to bring a bit of spring into your home In the dead of winter, spring blooming bulbs are especially welcome in the house. They fill any room with lively color (and maybe scent) and remind us that spring is just around the corner. Narcissus Forcing Narcissus in Water: • Place bulbs in a shallow bowl filled with gravel; mound gravel around sides of bulbs. • Add water so it barely touches bulbs. • Place bowl in a cool, dark location. • When roots start to grow, keep water below bulbs. • When top growth grows, move bowl to bright light but out of direct sunlight. • Bulbs bloom in about 6 weeks. Narcissus also grow well in vases with just water. Bulbs should be firm, without soft spots or scars. Bulbs with two "noses", or tips, will produce two stems. Forcing Narcissus in Soil: • Choose a wide pot about 6” deep with drainage holes in the bottom. Fill the pot loosely with potting mix. Set bulbs side by side, close but not touching, pointed end up, so that the tips are even with the pot rim. Do not press the bulbs into the mix. It should be loose to allow the roots to grow through it easily. Cover with additional potting mix, so the noses are barely covered. • Water thoroughly and empty drainage tray. • Daffodils need a cold treatment for 8-10 weeks. If you pre-chilled bulbs, you can skip this step. Move pot to a dark, cool (40-45°F) location such as a basement, unheated garage or refrigerator. -

Make Your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…

Make your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…. 1355 W 20 th Avenue Oshkosh, WI 54902 Phone: 920-966-1300 Friday and Sunday Bridal Package 2014 The following services and amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $600 deposit - $400 for banquet facility rental and $200 applied towards food and beverage Saturday Bridal Package 2014 The Following Services and Amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $1,000 deposit - $700 for banquet facility rental and $300 applied towards food and beverage $5,000 Food Minimum DINNER PLATED DINNER ENTREES POULTRY Chicken Forestiere 19.99 Chicken Piccata 19.99 6oz. -

The Vasa Star

THETHE VASA VASA STAR STAR VasastjärnanVasastjärnan PublicationPublication of of THE THE VASA VASA ORDER ORDER OF OF AMERICA AMERICA JULY-AUGUSTJULY-AUGUST 2010 2010 www.vasaorder.comwww.vasaorder.com MEB-E Art Björkner MEB-W Ed Netzel MEB-M Sten Hult MEB-S Ulf Alderlöf MEB-C Ken Banks VGS Gail Olson GS Joan Graham VGM Tore Kellgren GM Bill Lundquist GT Keith Hanlon The Grand Master’s Message Bill Lundquist Dear Vasa Brothers and Sisters, they were when we were founded in 1896, promoting our cul- I humbly and proudly accept the most prestigious office as tural heritage and providing a program of social fellowship. Grand Master of the Vasa Order and thank you for graciously We have suffered losses by death but many from lack of inter- electing me. I assume this office with excitement and much est. I plan to put programs in place to give you ideas to help enthusiasm but well aware of the challenges ahead. I am keep your current members interested and active as well as grateful and truly appreciative of your confidence in my ability make more interesting to potential members. New members to lead the Order for the next four years. I pledge to you that I bring in new enthusiasm, new ideas and new workers. will do my utmost to fulfill the goals I have set for this term. Scandinavians are no strangers to challenges. One such These include but are not limited to goals in the following challenge for all of us over the next four years is the reduced areas: Improvement in transparency between the Grand Lodge budget to The Vasa Star. -

Diary of a Vampeen

Vamp Chronicles DIARY OF A VAMPEEN Book One Christin M Lovell — DIARY OF A VAMPEEN Copyright © 2011 by Christin M Lovell Cover Image © konradbak This book may not be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission from the author. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. All characters and storylines are the property of the author and your support and respect is appreciated. The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. — VAMP CHRONICLES Diary of a Vampeen Vamp Yourself for War Hit the Road Jack The Innocence of White (short) Vamp Versus Vamp Darkness Falls Reflections (short) Vigilante The Break of Dawn (coming soon!) — DIARY OF A VAMPEEN Imagine living a human charade for fifteen years and never knowing it. Imagine being provided less than a week to learn and accept your family’s true heritage before it overtook you. Alexa Jackson, Lexi, is abruptly thrown onto this roller coaster and quickly learns that she can’t change fate, regardless of how many lifetimes she is given. She will be transformed into a vampeen on her sixteenth birthday, she will be called upon to fulfill a greater destiny within the dangerous world of vampires, and she will have to risk heartbreak and rejection if she ever wants a chance at love with Kellan, whether she likes it or not. — This book is dedicated to my daughter, Kali. -

The Path of Lucius Park and Other Stories of John Valley

THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley Approved: Sybil Baker Thomas P. Balázs Professor of English Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Rebecca Jones Professor of English (Committee Member) J. Scott Elwell A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of College of Arts and Sciences Dean of the Graduate School THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master’s of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 By Elijah David Carnley All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This thesis comprises a writer’s craft introduction and nine short stories which form a short story cycle. The introduction addresses the issue of perspective in realist and magical realist fiction, with special emphasis on magical realism and belief. The stories are a mix of realism and magical realism, and are unified by characters and the fictional setting of John Valley, FL. iv DEDICATION These stories are dedicated to my wife Jeana, my parents Keith and Debra, and my brother Wesley, without whom I would not have been able to write this work, and to the towns that served as my home in childhood and young adulthood, without which I would not have been inspired to write this work. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my Fiction professors, Sybil Baker and Tom Balázs, for their hard work and patience with me during the past two years. -

MEDIA KIT 2017/18 Welcome to the Inner Circle of DWP

MEDIA KIT 2017/18 Welcome to the inner circle of DWP There is no better way to reflect on the year passing us by and celebrate the start of a new one, quite like the kick-off of an impossible-to-resist portal to all things luxe and beautiful. The launch of the DWP - Insider editorial portfolio is exactly that. I find myself diving into the fascinating dynamics of two luxury industries, that rake in billions of dollars a year- weddings and travel. If you've found yourself staring down the barrel of done- and-dusted wedding trends, filled with nothing but aspirations to be innovative and different, then we've got your back. We have worked hard to create a platform that hand-picks the best in the business, scouting the most coveted frontrunners to become a ‘go-to’ journal for not only the bride and groom, but the entire bridal squad and all high-life aficionados. This inevitable next step in the Destination Wedding Planner Congress journey, takes an in- depth approach to the glamorous side of the luxury wedding industry - the elite ceremonies, the opulent jewelry and couture, and that of lavish destinations and their unique décor, food and wellness offerings. With each digital post and each bi-annual issue, we reveal the jewels in this season’s bridal crown– all perfectly bound in a must-have journal, that aims to connect partners and advertisers with select clientele; and enrich the reader culturally. Aishwarya Tyagi Editor, Destination Wedding Planner- Insider [email protected] The Reader Wedding Planners Wedding budgets and Brides-to-be ranging from from 65+ countries. -

The Heritage of Dress

Purchased by the AVary Stuart Boor Fund Founded A.D. 1893 Cooper Union Library^ THE HERITAGE OF DRESS PLATE I. Frontispiec Very early man in Java. {See page 5.) THE HERITAGE OF DRESS BEING NOTES ON THE HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF CLOTHES BY WILFRED MARK WEBB FELLOW OF THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON GKNERAL SECRETARY OF THE SELBORNE SOCIETY EDITOR OF " KNOWLEDGE " WITH TWELVE PLATES AND ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-NINE FIGURES IN THE TEXT NEW AND REVISED EDITION LONDON Zbc Uimes :Booft Club 1912 TO HIS WIFE HILDA E. WEBB AS A SMALL TOKEN OF AFFECTION THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY THE WRITER 20IOST PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION HTHE HERITAGE OF DRESS having been out of print for some time, the writer has taken the opportunity afforded him of issuing a second edition, and at the same time of making certain alterations in and additions to the text. Through the efforts of the present publishers the book has been produced in a compacter and handier form without curtailing it in any way, while the price has been halved ; a fact which should tend to carry the volume into those " quiet places " where Ruskin tells us science only lives " with odd people, mostly poor," WILFRED MARK WEBB. Odstock, Hanwell, April, 1912. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION TT would be difficult to find a subject of""more universal ^ interest than that of dress, and hosts of books have been written which deal \vT.th the attire that has been adopted at different times and by various nations or social classes. -

Veiling in Early Modern Europe by Susanna Burghartz (Translated by Jane Caplan)

ARTICLES Covered Women? Veiling in Early Modern Europe by Susanna Burghartz (translated by Jane Caplan) The veil and the headscarf have become deeply controversial signifiers of identity in recent years. In a conjuncture which is rather too hastily described as ‘a clash of civilizations’, in Christian-secular western Europe wearing the veil or scarf in public has come to epitomize a fundamentalist and antimodern Islamic culture that is opposed to freedom and emancipa- tion. Fierce debates about banning the scarf and veil have taken place in France and Germany, as also in other countries like Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland. The way in which this issue has escalated as a theme in the debate about identity politics is nowhere clearer than in the July 2010 decision of the French National Assembly to categorically ban the wearing of the full niqab or burka, in the name of human dignity and equality. In the opinion of many commentators, this amounted to a highly questionable readiness to enforce dignity and equality at the expense of the rights of individual freedom.1 The vehemence of the debate, and the ease with which the basic rights of individuals were overridden, demonstrate a preoccupation with questions of identity that far exceeds the material question of dress alone. In view of this vehemence, it is not surprising to find an ostensibly stark dichotomy of values in play: tradition as opposed to modernity, progress as opposed to reaction, religion to reason, and eman- cipation to oppression. But if we look at how the question of veiling has been negotiated in Europe since the Reformation, it becomes clear how deeply invested the West has been in this history of uncovering and concealing. -

SLT 1974 01 04.Pdf (14.42Mb)

HCd G- 5 •JIAS t•2.t SPP, I NC;r117.PT MtCHIrAtd '"?.'?^(-1 -isiertfleedie FARWELL, TEXAS FRIDAY. JANUARY 4. 1974 8 PAGES THE STATE LINE URELY TRIBUNE ERSONAL "OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF PARMER COUNTY" by John NUMBER 16 SIXTY-SECOND YEAR 15 CENTS ataaleatztzttnentS hp..e."Als,./4041W, 0.0,0%.W""ein.....01101.1.0W.WissNOWN .104•A"0.0%""inneWee. era w 01/2"..W W, The State of Texas is heading toward a major deci- Schools Change - sion in the handling of its - affairs. This will be the VANDALS LEAVE NOTES — Vandals who struck at the acceptance or rejection of a Grady Dodd and Vince Rowell homes in Friona during the Businesses List New Hours new State constitution. While it Christmas weekend left their "calling cards." Scattered has been loudly proclaimed around the ransacked and damaged homes were notes from Texico Schools will be or. uary 7, according to an- that the old, or one we are "The Green Fanthom." Sheriff Charlie Lovelace and his Mountain Time and Farwel nouncements by the respective currently abiding by, has deputies would like to meet the Green Fanthom. (Sheriff's Schools will operate on Central schools. become outmoded, the new or Office Photo Time, effective Monday, Jan- W. M. Roberts, superinten- proposed document appears to 441111111e p dent of the Farwell schools, us to be ahead of the wishes of said school hours will be from many Texans. 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and at While we are admitting that At Friona - Texico, Superintendent A. D. our "conservative vs liberal" McDonald said school hours bias is showing, we cannot help there will be 9 a.m. -

Utah State University Undergraduate Student Fieldwork Collection, 1979-2017

Utah State University undergraduate student fieldwork collection, 1979-2017 Overview of the Collection Creator Fife Folklore Archives. Title Utah State University undergraduate student fieldwork collection Dates 1979-2017 (inclusive) 1979 2015 Quantity 54 linear feet, (115 boxes) Collection Number USU_FOLK COLL 8: USU Summary Folklore projects collected by Utah State University students in fulfillment of graded credit requirements for coursework in undergraduate folklore classes (1979 to present). Repository Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections and Archives Division Special Collections and Archives Merrill-Cazier Library Utah State University Logan, UT 84322-3000 Telephone: 435-797-2663 Fax: 435-797-2880 [email protected] Access Restrictions Restrictions Open to public research. To access the collection a patron must have the following information: collection number, box number and folder number. The materials do not circulate and are available in USU's Special Collections and Archives. Patrons must sign and comply with the USU Special Collections and Archives Use Agreement and Reproduction Order form as well as any restrictions placed by the collector or informant(s). Languages English. Sponsor Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) grant, 2007-2008 Historical Note The Utah State University Undergraduate Student Fieldwork Collection consists of USU student folklore projects from 1979 to the present. The collection continues to grow. Content Description The Utah State University Undergraduate Student Fieldwork -

Costume News 2006:2 1(18)

ICOM Costume News 2006:2 1(18) COSTUME NEWS 2006:2 December 25, 2006 INTERNATIONAL COSTUME COMMITTEE COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DU COSTUME CONTENTS: Letter from the Chair Minutes, Annual General Meeting, October 13, 2006, Lund My first ICOM Costume Committee meeting ICOM Costume Committee annual meeting, 2007 Exhibitions Reviews ICOM Costume News, Spring 2007 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Season’s greetings to you all It was a great pleasure that so many members were able to attend the excellent meeting held in Copenhagen and Lund in October. It was particularly exciting, and the greatest compliment to the committee that Queen Margarethe of Denmark and Crown Princess Mary joined us for the opening session. With plans now afoot to publish the proceedings I think we should conclude we have enjoyed another very successful year. Please read the news of the next meeting of the committee which will take place in Vienna, Austria in August 2007. Our Austrian colleagues are working hard to put together a lively and interesting programme of costume lectures and visits which will work alongside the ICOM Triennial meeting activities. Vienna is a wonderful city with rich costume collections. I hope that many members will be able to take advantage of this opportunity to explore them. With all good wishes for a happy and peaceful 2007 Joanna Marschner Chairman ICOM Costume News 2006:2 2(18) MINUTES, ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING, OCTOBER 13, 2006, LUND Call to order, apologies The meeting was called to order by Chairman Joanna Marschner. 53 voting members were present. Regrets and greetings had been received from: Alexandra Palmer, Ioanna Papandrou, Suzanne McLean, Rainer Y, Margot Schindler, Vicki Berger, Karen Finch, Isabel Alvarado, Christine Stevens, Lillian Kozloski, Heidi Rasche, Anne Moonen.