The Heritage of Dress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalog DO NOT 1.) Daytime Phone Number Include the Cost of Postage and Handling, Which Will 2.) Date of Event Be Added at the Time of Shipping

est. 1948 EXCELLENCE IN AWARDS Quality Awards, Customer Satisfaction & Overall Experience South Fork, PA Ordering Information Office Hours Monday-Thursday: 8:00 AM to 4:30 PM EST, Friday: 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM EST Voice mail, fax and email are available 24/7 (800)346-9294 (814)495-4686 Fax: (814)495-9460 [email protected] ORDERING - When ordering please include the PRICING -All prices are subject to change without following information prior notification. Prices in this catalog DO NOT 1.) Daytime phone number include the cost of postage and handling, which will 2.) Date of event be added at the time of shipping. 3.) Quantity and color 4.) Catalog # or style name TERMS - All first time orders must be prepaid by 5.) Size check or credit card. We accept Visa, Mastercard, 6.) Wording of print American Express and Discover cards. Open account status may be established with approved MINIMUM ORDER - A minimum order charge of credit. All invoices must be paid within 30 days $20.00 will apply with the exception of stock items. after receipt of merchandise. Customers who do not comply with these terms will be required to DIES AND LOGOS - Stock logos are available at prepay for future orders. no additional charge. See our selection of standard stock dies on pages 35-37 of this catalog. For SHIPPING - All orders will be shipped via United custom designs or logos, see page 4 for die Parcel Service (UPS) or Postal Service (USPS). charges and artwork specifications. Please specify which carrier you prefer when ordering. -

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; to Include the Property of a Lady

Interiors, Homes & Antiques; To Include The Property Of A Lady, Eaton Square, London ( 24 Mar 2021 B) Wed, 24th Mar 2021 Lot 213 Estimate: £100 - £200 + Fees A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES A COLLECTION OF VINTAGE DRESSES to include a 1930s rose gold organza with a gold jacquard embroidery evening dress, with a square neckline, gold jacquard and green chiffon straps, a v back neckline, a A-line skirt and a gold jacquard and green chiffon sash decorates the back of the dress (74 cm bust, 74 cm waist, 146 cm from shoulder to hem); a 1930s ivory lace sleeveless evening dress, with a v neckline, lace straps and buttons covered in lace are used as zipper on the back, a full skirt and a silk slip (65 cm bust, 61 cm waist, 145 cm from shoulder to hem), the evening dress comes with a matching ivory lace shrug; an 1960s ivory silk wedding dress, with a jewel neckline embellished with white lace, long sleeves, buttons covered in silk are used as zipper on the back, a skirt with white lace hem and a cathedral train (83 cm bust, 83 cm waist, 132 cm from shoulder to front hem), the wedding dress comes with a bridal flower crown with tulle veil; a 1940s ivory silk evening dress, with a square neckline embellished with ivory lace and net, beads and a beige flower applique, short sleeves embellished with taupe net, beads and ivory lace, a skirt with a chapel train and a silk slip (63 cm bust, 58 cm waist, 165 cm from shoulder to front hem), a 1960s baby blue tullle evening dress, with a sweetheart neckline with spaghetti straps and a full skirt made up of layers of tulle and silk, with original label 'Salon Moderne. -

The Double-Bedded Room Batch2

THE DOUBLE-BEDDED ROOM. IN ONE ACT. BY JOHN MADDISON MORTON, ESQ., [Member of the Dramatic Authors' Society), AUTHOR OP Lend me Five Shillings, Three Cuckoos, Catch a Weasel, Where there's a Will there's a Way, John Dobbs, A Most Unwarrantable Intrusion, Going to the Derby, Your Life's in Danger, Midnight Watch, Box and Cox, Trumpeter's Wedding, Done on Both Sides, Poor Pillicoddy, Old Honesty, Young England, King and I, My Wife's SecondFloor, Who do they take me for? The Thumping Legacy, Milliners' Holiday, Wedding Breakfast, Irish Tiger, Attic Story, Who s the Composer ? Who's my Husband ? Slasher and Crasher, Prince for an Hour, Away with Melancholy, Waiting for an Omnibus, Betsy Baker, Who Stole the Pocket-Book ? Two Bonnycastles, From Village to Court, Grimshaw, Bagshaw, and Bradsha Rights and Wrongs of Women, Sent to the Tower, Our Wife, Brother Ben, Take Care of Dowb—, Wooing One's Wife, Margery Daw &c. &c. THOMAS HAILES LACY, 89, STRAND, LONDON, W.C. THE DOUBLE-BEDDED ROOM. First produced at the Haymarket Theatre, June 3rd, 1843, (under the management of Mr. B. Webster). MR. DULCIMER PIPES (Mus., Bac, and Organist).............................................. MR. W. FARREN. MAJOR MINUS........................................... MR. STRICKLAND. SPIGOT (Landlord of " The Yorkshire Grey").......................................................... MR. T. F. MATTHEWS. JOSEPH (his Head Waiter)........................ MR. CLARK. MRS. DEPUTY LOMAX........................... MRS. GLOVER. NANCY SPIGOT........................................... MRS. HUMBY. SCENE.— MR. DULCIMER PIPES.—Dark brown old-fashioned lappelled coat black breeches, white waistcoat, black hat, flannel dressing gown, nightcap, fawn-coloured travelling cap. MAJOR MINUS.—Military jacket, white collar and cuffs, pair of epaulettes, white trousers, blue cloth cap with gold band, fawn- coloured stuff Taglioni. -

Williquette Uccs 0892N 10490.Pdf (1.599Mb)

INVESTIGATING THE REASONS WOMEN WEAR CHOKER NECKLACES by HEATHER ANN WILLIQUETTE B.A., University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, 2015 A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Colorado Colorado Springs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Psychology 2019 ii This thesis for the Master of Arts degree by Heather Ann Williquette has been approved for the Department of Psychology by Laith Al-Shawaf, Chair Michael A. Kisley Michelle J. Escasa-Dorne Date 7-31-2019 iii Williquette, Heather Ann (M.A., Psychology) Investigating the Reasons Women Wear Choker Necklaces Thesis directed by Assistant Professor Laith Al-Shawaf ABSTRACT Choker necklaces have been around for centuries, carrying with them different cultural and societal connotations. However, little to no research investigates the reasons why women continue to wear choker necklaces today. Three studies were conducted in an attempt to explain why women may choose to wear choker necklaces. The first study (N = 204) examined women’s self-reports pertaining to her physical appearance and behaviors, and men’s perceptions of a woman in a photo on various measures. For the photo evaluations, we manipulated three different photos of three different women to create two conditions of a woman either wearing a choker or not wearing a choker. Men were randomly assigned to one of these conditions and were asked to evaluate the photograph. Findings reveal that women who self-reported wearing chokers more frequently had higher sociosexual orientations than women who self-reported wearing chokers less frequently, and men perceived the woman in the Choker condition to have a higher sociosexual orientation than the woman in the Nonchoker condition. -

Group Kit Contents

GROUP KIT CONTENTS PAGE INFORMATION 2 GENERAL INFORMATION 3 ROOMS 5 RESTAURANTS 11 BARS & DISCOTHEQUE 12 ENTERTAINMENTS AND SPORTS 15 KIDS CLUB 16 GROUP INFORMATION 28 EXCURSIONS 29 DIVING 31 CONTACT US 1 GENERAL INFORMATION VIVA WYNDHAM DOMINICUS BEACH & VIVA WYNDHAM DOMINICUS PALACE QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE Viva Wyndham Dominicus Beach & Viva Wyndham Dominicus Palace Bayahibe , La Romana , Republica Dominicana. Tel.: (809) 6865658 • Fax: (809) 686-5750, (809) 687-8583, (809) 2216805 Email: [email protected] www.vivaresorts.com LOCATION On the southeast coast of the Dominican Republic, facing the gorgeous island of Saona and Catalina. 72 Miles / 115 km, from Las Americas International Airport (approx. 1 hr. 40 min. drive), 62 Miles /100 km, from Punta Cana Airport (approx. 1 hr. 15 min. drive), 11 Miles /18 km, from La Romana International Airport /own (approx. 15 min. drive, 25 min.from La Romana. Voltage 110. The island of La Hispaniola was discovered by Christopher Columbus on December 5, 1492. Which is located in the Center of the Caribbean Sea. It is the second largest of the Greater Antilles, Cuba being the largest. The Island is shared by two nations: The Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.The country has seven airports: Las Américas International and Herrera in Santo Domingo; Punta Aguila and Punta Cana in the Eastern regions; María Montez in Barahona; Gregorio Luperon, Puerto Plata and Del Cibao, in Santiago de los Caballeros. The Main roads that begin in the city of Santo Domingo and conect the entire country are: the Duarte highway towards the South and Southwest regions and Las Américas highway, uniting Santo Domingo with the Southeast. -

Storage Treasure Auction House (CLICK HERE to OPEN AUCTION)

09/28/21 04:44:04 Storage Treasure Auction House (CLICK HERE TO OPEN AUCTION) Auction Opens: Tue, Nov 27 5:00am PT Auction Closes: Thu, Dec 6 2:00pm PT Lot Title Lot Title 0500 18k Sapphire .38ct 2Diamond .12ct ring (size 9) 0533 Watches 0501 925 Ring size 6 1/2 0534 Watches 0502 925 Chain 0535 Watches 0503 925 Chain 0536 Watches 0504 925 Bracelet 0537 Watches 0505 925 Tiffany company Braceltes 0538 Watch 0506 925 Ring size 7 1/4 0539 Watch 0507 925 Necklace Charms 0540 Watches 0508 925 Chain 0541 Watches 0509 925 Silver Lot 0542 Kenneth Cole Watch 0510 925 Chain 0543 Watches 0511 925 Silver Lot 0544 Pocket Watch (needs repair) 0512 925 Necklace 0545 Pocket Watch 0513 10K Gold Ring Size 7 1/4 0546 Earrings 0514 London Blue Topaz Gemstone 2.42ct 0547 Earrings 0515 Vanity Fair Watch 0548 Earrings 0516 Geneva Watch 0549 Earrings 0517 Watches 0550 Earrings 0518 Jordin Watch 0551 Earrings 0519 Fossil Watch 0552 Earrings 0520 Watches 0553 Necklace 0521 Watches & Face 0554 Necklaces 0522 Necklace 0555 Necklace Charms 0523 Watches 0556 Necklace 0524 Kenneth Cole Watch 0557 Necklaces 0525 Pennington Watch 0558 Belly Dancing Jewelry 0526 Watch 0559 Bracelet 0527 Watches 0560 Horseshoe Necklace 0528 Watches 0561 Beaded Necklaces 0529 Watch Parts 0562 Mixed Jewelry 0530 Watches 0563 Necklace 0531 Watch 0564 Earrings 0532 Watch 0565 Chains 1/6 09/28/21 04:44:04 Lot Title Lot Title 0566 Necklace 0609 Chains 0567 Necklace 0610 Necklace 0568 Necklace 0611 Necklace 0569 Necklace 0612 Bracelets 0570 Necklace 0613 Necklace With Black Hills gold Charms 0571 -

Uniform Dress and Appearance Regulations for the Royal Air Force Air Cadets (Ap1358c)

UNIFORM DRESS AND APPEARANCE REGULATIONS FOR THE ROYAL AIR FORCE AIR CADETS (AP1358C) HQAC (ATF) – DEC 2018 by authority of HQ Air Command reviewed by HQAC INTENTIONALLY BLANK 2 Version 3.0 AMENDMENT LIST RECORD Amended – Red Text Pending – Blue Text AMENDMENT LIST AMENDED BY DATE AMENDED NO DATE ISSUED Version 1.01 14 Aug 12 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 06 Aug 12 Version 1.02 22 Apr 13 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 15 Mar 13 Version 1.03 11 Nov 13 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 07 Nov 13 Version 1.04 05 Dec 13 FS Moss ATF HQAC 04 Dec 13 Version 1.05 19 Jun 14 FS Moss ATF HQAC 19 Jun 14 Version 1.06 03 Jul 14 FS Moss ATF HQAC 03 Jul 14 Version 1.07 19 Mar 15 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO(ATC) Mundy RWO L&SE 19 Mar 15 Version 2.00 05 Feb 17 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO(ATC) Mundy RWO L&SE 05 Feb 17 Version 3.00 04 Dec 18 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO Mundy RAFAC RWO L&SE 04 Dec 18 3 Version 3.0 NOTES FOR USERS 1. This manual supersedes ACP 20B Dress Regulations. All policy letters or internal briefing notices issued up to and including December 2018 have been incorporated or are obsoleted by this version. 2. Further changes to the Royal Air Force Air Cadets Dress Orders will be notified by amendments issued bi-annually or earlier if required. 3. The wearing of military uniform by unauthorised persons is an indictable offence under the Uniforms Act 1894. -

2020 Appendixes

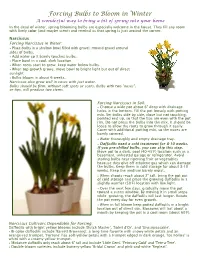

Forcing Bulbs to Bloom in Winter A wonderful way to bring a bit of spring into your home In the dead of winter, spring blooming bulbs are especially welcome in the house. They fill any room with lively color (and maybe scent) and remind us that spring is just around the corner. Narcissus Forcing Narcissus in Water: • Place bulbs in a shallow bowl filled with gravel; mound gravel around sides of bulbs. • Add water so it barely touches bulbs. • Place bowl in a cool, dark location. • When roots start to grow, keep water below bulbs. • When top growth grows, move bowl to bright light but out of direct sunlight. • Bulbs bloom in about 6 weeks. Narcissus also grow well in vases with just water. Bulbs should be firm, without soft spots or scars. Bulbs with two "noses", or tips, will produce two stems. Forcing Narcissus in Soil: • Choose a wide pot about 6” deep with drainage holes in the bottom. Fill the pot loosely with potting mix. Set bulbs side by side, close but not touching, pointed end up, so that the tips are even with the pot rim. Do not press the bulbs into the mix. It should be loose to allow the roots to grow through it easily. Cover with additional potting mix, so the noses are barely covered. • Water thoroughly and empty drainage tray. • Daffodils need a cold treatment for 8-10 weeks. If you pre-chilled bulbs, you can skip this step. Move pot to a dark, cool (40-45°F) location such as a basement, unheated garage or refrigerator. -

Make Your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…

Make your Wedding an Everlasting Dream to Remember…. 1355 W 20 th Avenue Oshkosh, WI 54902 Phone: 920-966-1300 Friday and Sunday Bridal Package 2014 The following services and amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $600 deposit - $400 for banquet facility rental and $200 applied towards food and beverage Saturday Bridal Package 2014 The Following Services and Amenities are included with your Wedding Reception/Dinner Complimentary ♥ A suite for the Bride and Groom the evening of your Reception o (Based on availability) ♥ Rooms for your guests at a guaranteed rate ♥ Round tables and chairs ♥ Linen tablecloths and napkins ♥ Skirted head table on risers with microphone ♥ Skirted cake table ♥ Skirted gift table and place card table ♥ Podium or table for guest book ♥ Easels for photo displays ♥ Dance floor ♥ Indoor pool and hot tub open 24 hours (children until 10:00pm) ♥ Also available, outdoor observation deck that seats up to 400 people. See Sales Department for details ♥ $1,000 deposit - $700 for banquet facility rental and $300 applied towards food and beverage $5,000 Food Minimum DINNER PLATED DINNER ENTREES POULTRY Chicken Forestiere 19.99 Chicken Piccata 19.99 6oz. -

Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments

Fordham Law Review Volume 66 Issue 4 Article 35 1998 Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments Samuel J. Levine Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Samuel J. Levine, Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments, 66 Fordham L. Rev. 1505 (1998). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol66/iss4/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments Cover Page Footnote Assistant Legal Writing Professor & Lecturer in Jewish Law, St. John's University School of Law; B.A. 1990, Yeshiva University; J.D. 1994, Fordham University; Ordination 1996, Yeshiva University; LL.M. 1996, Columbia University. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol66/iss4/35 RELIGIOUS SYMBOLS AND RELIGIOUS GARB IN THE COURTROOM: PERSONAL VALUES AND PUBLIC JUDGMENTS Samuel J. Levine* INTRODUCTION A S a nation that values and guarantees religious freedom, the fUnited States is often faced with questions regarding the public display of religious symbols. Such questions have arisen in a number of Supreme Court cases, involving both Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause issues. -

Awards for Every Ocassion

awards for every ocassion stock rosettes stock ribbons roll ribbons banners & pennants custom rosettes custom certificates beauty sashes awareness ribbons Table of Contents Custom Rosettes .......................................................... 3-13 Awards & Ribbons Catalog Custom Printed Ribbons..................................................14 When you’re looking for quality award and ribbon items, look Stock Ribbons & Rosettes ..............................................15 no further. We have taken the time and have the expertise to carefully handcraft our satin ribbons and rosettes for your Neck Ribbons & Beauty Sashes ...................................16 business! Choose from dozens of styles, sizes, colors and Tiaras & Scepters ............................................................17 award ribbon items to suit your many needs. Stock & Custom Certificates ..........................................18 • Various Rosette Designs • Custom Options Specialty Ribbons ............................................................19 • Numerous Imprint Color Choices Celluloid Buttons ..............................................................20 • Buttons, Certificates & More Color Chart ........................................................................21 Stock Logos................................................................. 22-23 Telephone Orders We want to produce your job right the first time, so we ask that large orders or orders requiring changes are in writing to reduce the possibility of errors. Quotes given -

A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women's Mantle

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 14, No. 6, pp.188~203(2010) A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women’s Mantle * Lee Sangrye ‧ Kim Hyejeong Professor, Dept. of Fashion Design, TongMyong University * Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing Industry, Hankyong National University Abstract This study purposed to identify the design and composition characteristics of mantle through a historical review of its change and development focusing on women’s dress. This analysis was particularly focused on the Victorian age because the variety of mantle designs introduced and popularized was wider than ever since ancient times to the present. For this study, we collected historical literature on mantle from ancient times to the 19 th century and made comparative analysis of design and composition, and for the Victorian age we investigated also actual items from the period. During the early Victorian age when the crinoline style was popular, mantle was of A‐ line silhouette spreading downward from the shoulders and of around knee length. In the mid Victorian age from 1870 to 1889 when the bustle style was popular, the style of mantle was changed to be three‐ dimensional, exaggerating the rear side of the bustle skirt. In addition, with increase in women’s suburban activities, walking costume became popular and mantle reached its climax. With the diversification of design and composition in this period, the name of mantle became more specific and as a result, mantle, mantelet, dolman, paletot, etc. were used. The styles popular were: it looked like half-jacket and half-cape. Ornaments such as tassels, fur, braids, rosettes, tufts and fringe were attached to create luxurious effects.