Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uniform Dress and Appearance Regulations for the Royal Air Force Air Cadets (Ap1358c)

UNIFORM DRESS AND APPEARANCE REGULATIONS FOR THE ROYAL AIR FORCE AIR CADETS (AP1358C) HQAC (ATF) – DEC 2018 by authority of HQ Air Command reviewed by HQAC INTENTIONALLY BLANK 2 Version 3.0 AMENDMENT LIST RECORD Amended – Red Text Pending – Blue Text AMENDMENT LIST AMENDED BY DATE AMENDED NO DATE ISSUED Version 1.01 14 Aug 12 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 06 Aug 12 Version 1.02 22 Apr 13 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 15 Mar 13 Version 1.03 11 Nov 13 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 07 Nov 13 Version 1.04 05 Dec 13 FS Moss ATF HQAC 04 Dec 13 Version 1.05 19 Jun 14 FS Moss ATF HQAC 19 Jun 14 Version 1.06 03 Jul 14 FS Moss ATF HQAC 03 Jul 14 Version 1.07 19 Mar 15 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO(ATC) Mundy RWO L&SE 19 Mar 15 Version 2.00 05 Feb 17 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO(ATC) Mundy RWO L&SE 05 Feb 17 Version 3.00 04 Dec 18 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO Mundy RAFAC RWO L&SE 04 Dec 18 3 Version 3.0 NOTES FOR USERS 1. This manual supersedes ACP 20B Dress Regulations. All policy letters or internal briefing notices issued up to and including December 2018 have been incorporated or are obsoleted by this version. 2. Further changes to the Royal Air Force Air Cadets Dress Orders will be notified by amendments issued bi-annually or earlier if required. 3. The wearing of military uniform by unauthorised persons is an indictable offence under the Uniforms Act 1894. -

Jewish Wigs and Islamic Sportswear: Negotiating Regulations of Religion and Fashion Emma Tarlo Goldsmiths, University of London

1 Jewish wigs and Islamic sportswear: Negotiating regulations of religion and fashion Emma Tarlo Goldsmiths, University of London Abstract This article explores the dynamics of freedom and conformity in religious dress prescriptions and fashion, arguing that although fashion is popularly perceived as liberating and religion as constraining when it comes to dress, in reality both demand conformity to normative expectations while allowing some freedom of interpretation. The article goes on to trace the emergence of new forms of fashionable religious dress such as the human-hair wigs worn by some orthodox Jewish women and the new forms of Islamic sportswear adopted by some Muslim women. It shows how these fashions have emerged through the efforts of religiously observant women to subscribe simultaneously to the expectations of fashion and religious prescription, which are seen to operate in a relationship of creative friction. In doing so, they invent new ways of dressing that push the boundaries of religious and fashion norms even as they seek to conform to them. Keywords Jewish wigs Islamic sportswear fashion religion burqini sheitel This article explores the dynamics of the relationship between religious clothing regulation and fashion by tracking the evolution of new sartorial inventions that have emerged through religious women’s dual concerns with fashion and faith. It proposes that although religious regulations relating to dress play an obvious role in limiting sartorial possibilities, they also provide a stimulus for creative responses that result in stylistic innovation. Viewed in this light, new forms of fashionable religious dress should be seen not so much as attempts to dilute or circumvent religious prescriptions and regulations, but rather as aspiring to obey the rules of fashion and the rules of religion simultaneously. -

A Short History of the Wearing of Clerical Collars in the Presbyterian Tradition

A Short History of the Wearing of Clerical Collars in the Presbyterian Tradition Introduction There does not seem to have been any distinctive everyday dress for Christian pastors up until the 6th century or so. Clergy simply wore what was common, yet muted, modest, and tasteful, in keeping with their office. In time, however, the dress of pastors remained rather conservative, as it is want to do, while the dress of lay people changed more rapidly. The result was that the dress of Christian pastors became distinct from the laity and thus that clothing began to be invested (no pun intended) with meaning. Skipping ahead, due to the increasing acceptance of lay scholars in the new universities, the Fourth Lateran council (1215) mandated a distinctive dress for clergy so that they could be distinguished when about town. This attire became known as the vestis talaris or the cassock. Lay academics would wear an open front robe with a lirripium or hood. It is interesting to note that both modern day academic and clerical garb stems from the same Medieval origin. Councils of the Roman Catholic church after the time of the Reformation stipulated that the common everyday attire for priests should be the cassock. Up until the middle of the 20th century, this was the common street clothes attire for Roman Catholic priests. The origin of the clerical collar does not stem from the attire of Roman priests. It’s genesis is of protestant origin. The Origin of Reformed Clerical Dress In the time of the Reformation, many of the Reformed wanted to distance themselves from what was perceived as Roman clerical attire. -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

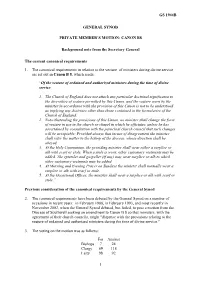

Gs 1944B General Synod Private Member's Motion

GS 1944B GENERAL SYNOD PRIVATE MEMBER’S MOTION: CANON B8 Background note from the Secretary General The current canonical requirements 1. The canonical requirements in relation to the vesture of ministers during divine service are set out in Canon B 8, which reads: “Of the vesture of ordained and authorized ministers during the time of divine service 1. The Church of England does not attach any particular doctrinal significance to the diversities of vesture permitted by this Canon, and the vesture worn by the minister in accordance with the provision of this Canon is not to be understood as implying any doctrines other than those contained in the formularies of the Church of England. 2. Notwithstanding the provisions of this Canon, no minister shall change the form of vesture in use in the church or chapel in which he officiates, unless he has ascertained by consultation with the parochial church council that such changes will be acceptable: Provided always that incase of disagreement the minister shall refer the matter to the bishop of the diocese, whose direction shall be obeyed. 3. At the Holy Communion, the presiding minister shall wear either a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. When a stole is worn, other customary vestments may be added. The epistoler and gospeller (if any) may wear surplice or alb to which other customary vestments may be added. 4. At Morning and Evening Prayer on Sundays the minister shall normally wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. 5. At the Occasional Offices, the minister shall wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole.” Previous consideration of the canonical requirements by the General Synod 2. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

A Comparison Framework on Islamic Dress Code and Modest Fashion in the Malaysian Pjaee, 17 (7) (2020) Fashion Industry

A COMPARISON FRAMEWORK ON ISLAMIC DRESS CODE AND MODEST FASHION IN THE MALAYSIAN PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) FASHION INDUSTRY A COMPARISON FRAMEWORK ON ISLAMIC DRESS CODE AND MODEST FASHION IN THE MALAYSIAN FASHION INDUSTRY Zulina Kamarulzaman, Nazlina Shaari Zulina Kamarulzaman, Nazlina Shaari: A Comparison Framework on Islamic Dress Code and Modest Fashion in the Malaysian Fashion Industry-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords— Conceptual framework, Islamic dress code, modest fashion, Malaysia. ABSTRACT The influence of social media trends in the current world has significantly impacted the fashion industry. Hence, the rise of the Islamic fashion culture has expanded to Western countries, which no longer consider Islamic fashion to be dull and boring. Islamic fashion was also constantly misjudged, even by Muslims, as the idea of covering the body and head with a veil or hijab and wearing body-hugging clothes with a bit of exposed hair is accepted as Islamic wear. This indicated a shift of perspective from a conservative to modern culture in Islamic attire, with a lack of understanding of the difference between the two concepts. Therefore, this study identifies the comparison between the Islamic dress code and modest fashion. The analysis performed used the literature review of previous studies over five years, between 2015 and 2020, using databases from Google Scholar and Scopus. However, only 15 articles were discussed in this study. The review of past literature was based on the crucial keywords related to this study. Modest fashion, the Islamic dress code, and Islamic fashion in Malaysia was the focus of the keywords research. -

Ancient Civilizations Huge Infl Uence

India the rich ethnic mix, and changing allegiances have also had a • Ancient Civilizations huge infl uence. Furthermore, while peoples from Central Asia • The Early Historical Period brought a range of textile designs and modes of dress with them, the strongest tradition (as in practically every traditional soci- • The Gupta Period ety), for women as well as men, is the draping and wrapping of • The Arrival of Islam cloth, for uncut, unstitched fabric is considered pure, sacred, and powerful. • The Mughal Empire • Colonial Period ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS • Regional Dress Harappan statues, which have been dated to approximately 3000 b.c.e. , depict the garments worn by the most ancient Indi- • The Modern Period ans. A priestlike bearded man is shown wearing a togalike robe that leaves the right shoulder and arm bare; on his forearm is an armlet, and on his head is a coronet with a central circular decora- ndia extends from the high Himalayas in the northeast to tion. Th e robe appears to be printed or, more likely, embroidered I the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges in the northwest. Th e or appliquéd in a trefoil pattern. Th e trefoil motifs have holes at major rivers—the Indus, Ganges, and Yamuna—spring from the the centers of the three circles, suggesting that stone or colored high, snowy mountains, which were, for the area’s ancient inhab- faience may have been embedded there. Harappan female fi gures itants, the home of the gods and of purity, and where the great are scantily clad. A naked female with heavy bangles on one arm, sages meditated. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Religion' Janet L

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 1988 Religious Symbols and the Establishment of a National 'Religion' Janet L. Dolgin Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Janet L. Dolgin, Religious Symbols and the Establishment of a National 'Religion', 39 Mercer L. Rev. 495 (1988) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religious Symbols and the Establishment of a National 'Religion' by Janet L. Dolgin* I. INTRODUCTION In its last few terms, the Supreme Court has decided over a half-dozen major religion clause' cases.2 While the Court has not jettisoned accepted modes of first amendment analysis, the decisions have involved an impor- tant, if subtle, shift regarding the place and significance of religion and religious identity in American life. The religion cases that the Court has decided in the past several years suggest an alteration in the tone, if not the method, of first amendment analysis. This alteration reflects, and is reflected in, changes in the larger society. Correlatively, the religion cases frame many concerns that extend beyond the first amendment, per se, to * Assistant Professor of Law, Hofstra University School of Law. -

The Jewish Symbols

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI Przegląd Narodowościowy – Review of Nationalities • Jews nr 6/2016 DOI: 10.1515/pn-2016-0014 ISSN 2084-848X (print) ISSN 2543-9391 (on-line) Krzysztof Łoziński✴ The Jewish symbols KEYWORDS: Jew, Judaism, symbol, archetype, Judaica SŁOWA KLUCZOWE: Żyd, judaizm, symbol, archetyp, judaica In every culture, people have always used symbols giving them sense and assigning them a specific meaning . Over the centuries, with the passage of time religious sym- bols have mingled with secular symbols . The charisms of Judaism have tuallymu in- termingled with the Christian ones taking on a new tribal or national form with in- fluences of their own culture . The aim of this article is to analyze and determine the influence of Judaic symbols on religious and social life of the Jews . The article indicates the sources of symbols from biblical times to the present day . I analyzed the symbols derived from Jewish culture, and those borrowed within the framework of acculturation with other communities as well . By showing examples of the interpenetration of cultures, the text is anattempt to present a wide range of meanings symbols: from the utilitarian, through religious, to national ones . It also describes their impact on the religious sphere, the influence on nurturing and preserving the national-ethnic traditions, sense of identity and state consciousness . The political value of a symbol as one of the elements of the genesisof the creation of the state of Israel is also discussed . “We live in a world of symbols, a world of symbols lives in us “ Jean Chevalier The world is full of symbols . -

The Wearing of Christian Baptismal Crosses ***

Stato, Chiese e pluralismo confessionale Rivista telematica (www.statoechiese.it), n. 32/2012 29 ottobre 2012 ISSN 1971- 8543 Philip Ryabykh*, Igor Ponkin** (*hegumen, representative of Russian Orthodox Church in Strasbourg; ** director of the Institute for State-Confessional Relations and Law) The wearing of Christian baptismal crosses *** SUMMARY: 1. On the religious significance of baptismal crosses and grounds for the need for Orthodox Christian believers to wear them – 2. On the illegitimate nature of the ban imposed by the state on the wearing of baptismal symbols of Christian religious affiliation – 3. Absence of any grounds for assessing the religious rite of wearing Christian baptismal crosses as a threat to public safety, public order, health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others – 4. The groundless emasculation, denial and reduction of the religious meaning and importance of Christian baptismal crosses. 1 - On the religious significance of baptismal crosses and grounds for the need for Orthodox Christian believers to wear them In Orthodox Christianity, the need to wear around one’s neck some symbols of religious affiliation such as Christian crosses (small items symbolizing Christian crucifix) is determined by the religious significance they have had in Orthodox Church since ancient times. It is an integral part of the freedom to confess one’s faith in the context of age-old Christian tradition. It is also a rule prescribed to Orthodox Christians by canonical regulation norms (canon law, lex canonical). Through the observance of this rule, the significance of the cross as a symbol of Christian self-sacrifice sustains the religious self-identification of believers.