Modality in Tharu: a Comparative Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

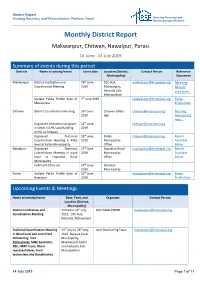

Monthly District Report

District Report Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform, Nepal Housing Recovery and Reconstruction Platform Monthly District Report Makwanpur, Chitwan, Nawalpur, Parasi 14 June - 14 July 2019 Summary of events during this period Districts Name of activity/event Event date Location (District, Contact Person Reference Municipality) Document Makwanpur District Facilitation and 18th June DCC Hall, [email protected] Meeting Coordination Meeting 2019 Makwanpur, Minute Hetauda Sub- click here.. Metropolitan Update Palika Profile data of 7th June 2019 [email protected] Palika Makwanpur Profile Data Chitwan District Coordination Meeting 26th June Chitwan GMaLi [email protected] Meeting 2019 Hall Minute click here... Organized interaction program 24th June, [email protected] in GMALI DLPIU and Building 2019 DLPIU at Chitwan Organized Technical 26th june, Kalika [email protected] Report Coordination Meeting in Plika 2019 Municipality Available level at Kalika Municipality Office Below Nawalpur Organized Technical 27th June Hupsekot Rural [email protected] Report Coordination Meeting in ward 2019 Municipality Available level at Hupsekot Rural Office Below Municipality Field visit Carry out 27th June, Devchuli 2019 Municipality Parasi Update Palika Profile data of 12th June [email protected] Palika Nawalpur 2019 Profile Data Upcoming Events & Meetings Name of activity/event Date, Time, and Organizer Contact Person Location (District, Municipality) District Facilitation and Tentative 19th July, DCC/GMaLI/HRRP [email protected] Coordination Meeting 2019; DCC Hall, Hetauda, Makwanpur Technical Coordination Meeting 24th July to 26th July, Joint Monitoring Team [email protected] in Ward level and Joint Field 2019 Bakaiya Rural Monitoring Visit Municipality, Participants: M&E Specialist, Makwanpur Gadhi DSE, HRRP team, Ward and Hetauda Sub- representatives, local Metropolitan technicians and Beneficiaries. -

Livlihood Strategy of Rana Tharu

LIVLIHOOD STRATEGY OF RANA THARU : A CASE STUDY OF GETA VDC OF KAILALI DISTRICT A Thesis Submitted to: Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University, in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of the Master Of Arts (MA) In Rural Development By VIJAYA RAJ JOSHI Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University TU Regd. No.: 6-2-327-108-2008 Roll No.: 204/068 September 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled Livelihood Strategy of Rana Tharu : A Case Study of Geta VDC of Kailali District submitted to the Central Department of Rural Development, Tribhuvan University, is entirely my original work prepared under the guidance and supervision of my supervisor Prof Dr. Prem Sharma. I have made due acknowledgements to all ideas and information borrowed from different sources in the course of preparing this thesis. The results of this thesis have not been presented or submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree or for any other purposes. I assure that no part of the content of this thesis has been published in any form be ........................ VIJAYA RAJ JOSHI Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University TU Regd. No. : 6-2-327-108-2008 Roll No : 204/068 Date: August 21, 2016 2073/05/05 . 2 RECOMMENDATION LETTER This is to certify that Mr. Vijaya Raj Joshi has completed this thesis work entitled Livelihood Strategy of Rana Tharu : A Case Study of Geta VDC of Kailali District under my guidance and supervision. I recommend this thesis for final approval and acceptance. _____________________ Prof. Dr. Prem Sharma (Supervisor) Date: Sep 14, 2016 2073/05/29 . -

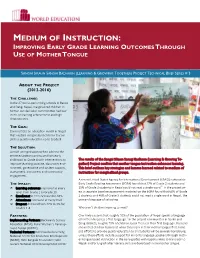

SSSB Medium of Instruction Brief

MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION: IMPROVING EARLY GRADE LEARNING OUTCOMES THROUGH USE OF MOTHER TONGUE SANGAI SIKAUN SANGAI BADHAUN (LEARNING & GROWING TOGETHER) PROJECT TECHNICAL BRIEF SERIES # 3 ABOUT THE PROJECT (2012-2016) THE CHALLENGE: In the 27 worst-performing schools in Banke and Dang, Nepal, marginalized children in former bonded labor communities had low levels of learning achievement and high dropout rates. THE GOAL: Demonstrate an education model in Nepal that enables marginalized children to com- plete a quality education up to Grade 8. THE SOLUTION: A multi-pronged approach to address the entire education continuum from early childhood to Grade 8 with interventions to The results of the Sangai Sikaun Sanagi Badhaun (Learning & Growing To- improve teaching practice, classroom envi- gether) Project confirm that mother tongue instruction enhances learning. ronment, governance and system support, This brief outlines key strategies and lessons learned related to medium of assessment, and parent and community instruction for marginalized groups. engagement. A recent United States Agency for International Development (USAID) nationwide THE IMPACT: Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) found that 37% of Grade 2 students and 1 Learning outcomes improved at every 19% of Grade 3 students in Nepal could not read a single word. In the project ar- level from Grade 1 to Grade 10 ea, a separate baseline assessment modeled on the EGRA found that 68% of Grade Enrollment in ECD increased to 93% 2 students and 40% of Grade 3 students could not read a single word in Nepali, the Attendance increased at every level. primary language of schooling. Dropout declined from 22% to 3% for Grades 1-8 Why aren’t children learning to read? PARTNERS: One likely cause is that roughly 55% of the population of Nepal speaks a language 2 Implementing Partners: Backwards Society other than Nepali as a first language. -

Hindi and Urdu (HIND URD) 1

Hindi and Urdu (HIND_URD) 1 HINDI AND URDU (HIND_URD) HIND_URD 111-1 Hindi-Urdu I (1 Unit) Beginning college-level sequence to develop basic literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari script only. Prerequisite - none. HIND_URD 111-2 Hindi-Urdu I (1 Unit) Beginning college-level sequence to develop basic literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari script only. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 111-1 or equivalent. HIND_URD 111-3 Hindi-Urdu I (1 Unit) Beginning college-level sequence to develop basic literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari script only. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 111-2 or equivalent. HIND_URD 116-0 Accelerated Hindi-Urdu Literacy (1 Unit) One-quarter course for speakers of Hindi-Urdu with no literacy skills. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts; broad overview of Hindi-Urdu grammar. Prerequisite: consent of instructor. HIND_URD 121-1 Hindi-Urdu II (1 Unit) Intermediate-level sequence developing literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 111-3 or equivalent. HIND_URD 121-2 Hindi-Urdu II (1 Unit) Intermediate-level sequence developing literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 121-1 or equivalent. HIND_URD 121-3 Hindi-Urdu II (1 Unit) Intermediate-level sequence developing literacy and oral proficiency in Hindi-Urdu. Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. Prerequisite: grade of at least C- in HIND_URD 121-2 or equivalent. HIND_URD 210-0 Hindi-Urdu III: Topics in Intermediate Hindi-Urdu (1 Unit) A series of independent intermediate Hindi-Urdu courses, developing proficiency through readings and discussions. -

On Documenting Low Resourced Indian Languages Insights from Kanauji Speech Corpus

Dialectologia 19 (2017), 67-91. ISSN: 2013-2247 Received 7 December 2015. Accepted 27 April 2016. ON DOCUMENTING LOW RESOURCED INDIAN LANGUAGES INSIGHTS FROM KANAUJI SPEECH CORPUS Pankaj DWIVEDI & Somdev KAR Indian Institute of Technology Ropar*∗ [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract Well-designed and well-developed corpora can considerably be helpful in bridging the gap between theory and practice in language documentation and revitalization process, in building language technology applications, in testing language hypothesis and in numerous other important areas. Developing a corpus for an under-resourced or endangered language encounters several problems and issues. The present study starts with an overview of the role that corpora (speech corpora in particular) can play in language documentation and revitalization process. It then provides a brief account of the situation of endangered languages and corpora development efforts in India. Thereafter, it discusses the various issues involved in the construction of a speech corpus for low resourced languages. Insights are followed from speech database of Kanauji of Kanpur, an endangered variety of Western Hindi, spoken in Uttar Pradesh. Kanauji speech database is being developed at Indian Institute of Technology Ropar, Punjab. Keywords speech corpus, Kanauji, language documentation, endangered language, Western Hindi DOCUMENTACIÓN DE OBSERVACIONES SOBRE LENGUAS HINDIS DE POCOS RECURSOS A PARTIR DE UN CORPUS ORAL DE KANAUJI Resumen Los corpus bien diseñados y bien desarrollados pueden ser considerablemente útiles para salvar la brecha entre la teoría y la práctica en la documentación de la lengua y los procesos de revitalización, en la ∗* Indian Institute Of Technology Ropar (IIT Ropar), Rupnagar 140001, Punjab, India. -

Provincial Summary Report Province 3 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Province 3 Province Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6360-9 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance......…………………………………….............................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 3 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit….….27 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...48 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…62 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...69 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...77 Table 8. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Tribes in Uttarakhand: Status and Diversity Dr

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development Online ISSN: 2349-4182, Print ISSN: 2349-5979, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.72 www.allsubjectjournal.com Volume 4; Issue 1; January 2017; Page No. 89-93 Tribes in Uttarakhand: Status and diversity Dr. Digar Singh Farswan H.O.D B.Ed. Department, Devbhumi Institute of Professional Education, Lalpur, Rudrapur, Distt.- Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand, India Abstract Tribes of Uttarakhand mainly comprise five major groups namely Jaunsari tribe, Tharu tribe, Raji tribe, Buksa tribe and Bhotiyas. In terms of population Jaunsari tribe is the largest tribal group of the state. Tribes of Uttarakhand represent the ethnic groups residing in the state. Every district of Uttarakhand has more or less a moderate percentage of tribal population. In the state of Uttarakhand, the main concentration of tribal population is in the rural areas. As per records, around 94.50 percent of total tribal population resides in rural areas and the remaining percentage of tribal population lives in urban centers. It is said that officially Uttarakhand is the home of around five tribes. These tribes of Uttarakhand have been scheduled in the Constitution of India. Historical records suggest that the tribes of Uttarakhand are earliest settlers of this region of North India. In the past, their main concentrations were confined to remote hilly and forested areas. The tribes of Uttarakhand have retained their age old traditional ways of living. They represent the distinctive culture and traits of a primitive life. Their traditional norms and socio-cultural practices determine their ethnicity. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Membership Register MBR0009

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JULY 2020 CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL DIST IDENT NBR CLUB NAME COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 5117 026070 BIRGANJ NEPAL 325B2 4 07-2020 46 0 0 0 0 0 46 5117 029868 HIMALAYAS PATAN NEPAL 325B2 4 05-2020 25 0 0 0 0 0 25 5117 035305 HETAUDA NEPAL 325B2 4 12-2019 34 0 0 0 0 0 34 5117 040820 NARAYANGARH NEPAL 325B2 4 04-2020 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 5117 042916 BIRGANJ ADARSHNAGAR NEPAL 325B2 4 06-2020 42 0 0 0 0 0 42 5117 042917 BUTWAL NEPAL 325B2 4 04-2020 87 0 0 0 0 0 87 5117 044334 PALPA NEPAL 325B2 4 05-2020 49 0 0 0 0 0 49 5117 045854 SIDDHARATHANAGAR NEPAL 325B2 4 06-2020 72 0 0 0 0 0 72 5117 046792 DHANGADHI TOWN NEPAL 325B2 4 04-2020 47 0 0 0 0 0 47 5117 047592 BIRGANJ GREATER NEPAL 325B2 4 07-2020 9 0 0 0 -6 -6 3 5117 047955 KATHMANDU EVEREST NEPAL 325B2 4 01-2020 10 0 0 0 0 0 10 5117 056224 KATHMANDU TRIPURESWOR NEPAL 325B2 4 07-2020 43 1 0 0 -25 -24 19 5117 056487 LALITPUR PAGODA CITY NEPAL 325B2 4 04-2020 22 0 0 0 0 0 22 5117 057111 KATHMANDU VALLEY WEST NEPAL 325B2 4 04-2020 11 0 0 0 0 0 11 5117 058172 DANG NEPAL 325B2 4 07-2020 46 1 0 0 -1 0 46 5117 058240 KRISHNANAGAR NEPAL 325B2 4 07-2020 11 4 0 0 -1 3 14 5117 059380 BIRGANJ GATEWAY NEPAL 325B2 4 06-2020 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 5117 060132 NEPALGANJ NEPAL 325B2 4 06-2020 66 0 0 0 0 0 66 5117 060588 BARDIYA NEPAL 325B2 4 07-2020 19 0 0 0 0 0 19 5117 060698 RATNANAGAR NEPAL 325B2 4 07-2020 16 8 1 0 0 9 25 5117 061182 NARAYANGARH