Monograph No 43.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Election 2018 Update-Ii - Fafen General Election 2018

GENERAL ELECTION 2018 UPDATE-II - FAFEN GENERAL ELECTION 2018 Update-II April 01 – April 30, 2018 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) initiated its assessment of the political environment and implementation of election-related laws, rules and regulations in January 2018 as part of its multi-phase observation of General Election (GE) 2018. The purpose of the observation is to contribute to the evolution of an election process that is free, fair, transparent and accountable, in accordance with the requirements laid out in the Elections Act, 2017. Based on its observation, FAFEN produces periodic updates, information briefs and reports in an effort to provide objective, unbiased and evidence-based information about the quality of electoral and political processes to the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), political parties, media, civil society organizations and citizens. General Election 2018 Update-II is based on information gathered systematically in 130 districts by as many trained and non-partisan District Coordinators (DCs) through 560 interviews1 with representatives of 33 political parties and groups and 294 interviews with representative of 35 political parties and groups over delimitation process. The Update also includes the findings of observation of 559 political gatherings and 474 ECP’s centres set up for the display of preliminary electoral rolls. FAFEN also documented the formation of 99 political alliances, party-switching by political figures, and emerging alliances among ethnic, tribal and professional groups. In addition, the General Election 2018 Update-II comprises data gathered through systematic monitoring of 86 editions of 25 local, regional and national newspapers to report incidents of political and electoral violence, new development schemes and political advertisements during April 2018. -

The Sindh Perchar

OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE WORLD SINDHI CONGRESS The Sindh Perchar S UMMER 2002 V OLUME 11, I SSUE 1 SUGGESTED DONATION: $3.0/ £ 1.0 Military Assumes Permanent Role in Governance of Pakistan Is Pakistan an Ally in War London, July 2002, General Musharaf—the self imposed President of Pakistan— Against Terrorism? recently announced a set of ‘constitutional amendments’ legitimizing his military Editorial Desk, 2002 dictatorship. These amendments guarantee a permanent and dominant role for Pakistan is considered as an important military in all future governments in Pakistan. These new changes grant President ally in the current international coali- (Gen Musharaf) the power to dissolve Parliament and dismiss the prime minister in tion against terrorism. Looking back any future elected government. A ‘National Security Council’ having powers to on Pakistan’s involvement in terrorism sack the cabinet and dissolve parliament will be formed. It will also oversee the itself, inside and outside its borders, (Continued on page 8) make Pakistan a ‘shaky ally.’ All wars are to be opposed. Though on rational basis, we see that the ter- Sindhis Protest Over Thal Canal rorism is needed to be dealt with ap- Calling it an Economic and Ecological Disaster propriate resistance. World does not need any more of Sept 11 incidents. London, March, 2002 , A big rally was cluded a delegation of MQM headed by However, that at this time, while organized in front of Pakistan High Saleem Shehzad, Balach Marri (son of preaching for peace, we must also ana- Commission, -

REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan

October 2000 Vol. 12, No. 6 (C) REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan I. SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Pakistan..............................................................................................................................3 To the International Community ............................................................................................................................5 III. BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................................5 Musharraf‘s Stated Objectives ...............................................................................................................................6 IV. CONSOLIDATION OF MILITARY RULE .......................................................................................................8 Curbs on Judicial Independence.............................................................................................................................8 The Army‘s Role in Governance..........................................................................................................................10 Denial of Freedoms of Assembly and Association ..............................................................................................11 -

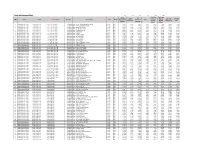

Final Merit List of Candidates Applied for Admission in Bs Medical Laboratory

BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION - 2020-2021 FINAL MERIT LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR ADMISSION IN BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION 2020-2021 LIAQUAT UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, JAMSHORO DISTRICT - BADIN (BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) - 01 - SEAT - MERIT) Test Test Int. Total Merit Inter A / Level Test Form No. Name of Candidates Fathers Name Surname Gender DOB District Seat Marks 50% score Positon Obt 50% Year Inter% Grade No. Marks 1 4841 Habesh Kumar Veero Mal Khattri Male 1/11/2001 BADIN 2019 905 82.273 A1 719 82 41 41.136 82.136 District: BADIN - WAITING Menghwar 1496 Akash Kumar Mansingh Male 10/16/2001 BADIN 2020 913 83 A1 167 78 39 41.5 80.5 2 Bhatti 3 1215 Janvi Papoo Kumar Lohana Female 2/11/2002 BADIN 2020 863 78.455 A 894 82 41 39.227 80.227 4 3344 Bushra Muhammad Ayoub Kamboh Female 9/30/2000 BADIN 2019 835 75.909 A 490 82 41 37.955 78.955 5 1161 Chanderkant Papoo Kumar Lohana Male 3/8/2003 BADIN 2020 889 80.818 A1 503 76 38 40.409 78.409 6 3479 Bushra Amjad Amjad Ali Jat Female 4/20/2001 BADIN 2019 848 77.091 A 494 73 36.5 38.545 75.045 7 4306 Noor Ahmed Ghulam Muhammad Notkani Male 10/12/2001 BADIN 2020 874 79.455 A 1575 70 35 39.727 74.727 Muhammad Talha 2779 Hasan Nasir Rajput Male 7/21/2001 BADIN 2020 927 84.273 A1 1378 65 32.5 42.136 74.636 8 Nasir 9 3249 Vandna Dev Anand Lohana Female 3/21/2002 BADIN 2020 924 84 A1 2294 65 32.5 42 74.5 10 2231 Sanjai Eshwar Kumar Luhano Male 8/17/2000 BADIN 2020 864 78.546 A 1939 70 35 39.273 74.273 RANA RAJINDAR 3771 RANA AMAR -

Oscillating in a Chasm 2 | P a G E

SPEARHEAD RESEARCH 1 | P a g e SPECIAL REPORT October 2012 Balochistan: Oscillating in a Chasm 2 | P a g e Balochistan: Oscillating in a Chasm By Zoon Ahmed Khan http://spearheadresearch.org Email: [email protected] Tel: +92 42 3662 2335 +92 42 3662 2336 Fax: +92 42 3662 2337 Office 17, 2nd Floor, Parklane Towers, 172 Tufail Road, Cantonment Lahore - Pakistan 3 | P a g e Abstract “Rule the Punjabis, intimidate the Sindhis, buy the Pashtun and honour the Baloch” For the colonial master a delicate balance between resource exploitation and smooth governance was the fundamental motive. Must we assume that this mindset has seeped into the governmentality of Islamabad? And if it has worked: are these provinces in some way reflective of stereotypes strong enough to be regarded as separate nations? These stereotypes are reflective of the structural relationships in these societies and have been discovered, analyzed and, at times, exploited. In the Baloch case the exploitation seems to have become more apparent because this province has been left in the waiting room of history through the prisms of social, political and economic evolution. Balochistan’s turmoil is a product of factors that this report will address. Looking into the current snapshot, and stakeholders today, the report will explain present in the context of a past that media, political parties and other stakeholders are neglecting. 4 | P a g e 5 | P a g e Contents Introduction: ............................................................................................................................ -

The Science of Society Has Its Place in Understanding the Collective Cognizant Which Is Sum Total of Beliefs, Sentiments, Thoughts and Social Collaborations

Grassroots, Vol.51, No.II July-December 2017 SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF SYMBOLS OF SUFISM AS DEPICTED IN SHAH LATIF’S POETRY Ali Murad Lajwani Dr.Nagina Parveen Soomro ABSTRACT People living on earth are socially connected due to their social needs and social actions. Such social actions and social needs are root-cause of various social relationships. The art of building true relationships is one of social actions which create harmony and tolerance among the people. Shah’s poetry offers openness to demonstrate good behavior and make global relationships with glowing understanding of spiritual concepts about different religions. There are poetic signs and symbols which connect hearts of people together in the same way as social needs are ground reasons of peaceful relationships. This poetry is a creative attempt with many signs and symbols of love, peace and spirituality. Like the poetic words are very catchy and appealing with unique spiritual flavour that starts its function of connecting people together while enjoying the reading as well as listening spiritual music (Shah-Jo-Raag). The unique flavour of reciting verses is genuinely food for human inner-soul and thought that creates a collective wish of social solidarity. Through the spiritual symbols of Shah’s poetry many intellectual scholars are globally connected in the present era of terrorism and frustrations because the continuous pursuit of reading Shah’s poetry and listening spiritual music promotes sense of spirituality among the people on becoming peaceful citizens. This worthwhile poetry helps on improving the sense of spirituality and such capability is the basic need of our present as well as future generations. -

Motion Anwar Lal Dean, Bahramand Khan Tangi

SENATE SECRETARIAT ORDERS OF THE DAY for the meeting of the Senate to be held at 02:00 p.m. on Thursday, the 1'r August, 20 19. 1, Recitation from the Holy Quran. MOTION 2, SENATORS RAJA MUHAMMAD ZAFAR-UL-HAQ, LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION, ATTA UR REHMAN, MOLVI FAIZ MUHAMMAD, ABIDA MUHAMMAD AZEEM, AGHA SHAHZAIB DURRANI, RANA MAHMOOD UL HASSAN, PERVAIZ RASHEED, MUSADIK MASOOD MALIIC SITARA AYAZ, MUHAMMAD JAVED ABBASI, MUHAMMAD USMAN KHAN KAKAR, MIR KABEER AHMED MUHAMMAD SHAHI, MOLANA ABDUL GHAFOOR HAIDERI, MUHAMMAD TAHIR BIZINJO, MUSHAHID ULLAH KHAN, SALEEM ZIA, MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI KHAN JUNEJO, GHOUS MUHAMMAD KHAN NIAZI, RANA MAQBOOL AHMAD, DR. ASIF KIRMANI, DR. ASAD ASHRAF, SARDAR MUHAMMAD SHAFIQ TAREEN, SHERRY REHMAN, MIAN RAZA RABBANI, FAROOQ HAMID NAEK, ABDUL REHMAN MALIK DR. SIKANDAR MANDHRO, ISLAMUDDIN SHAIKH, RUBINA KHALID, GIANCHAND, KHANZADA KHAN, SASSUI PALIJO, MOULA BUX CHANDIO, MUSTAFA NAWAZ KHOKHA& SYED MUHAMMAD ALI SHAH ]AMOT, IMAMUDDIN SHOUQEEN, ENGR. RUKHSANA ZUBERI, QURATULAIN MARRI, KESHOO BAI, ANWAR LAL DEAN, BAHRAMAND KHAN TANGI AND MIR MUHAMMAD YOUSAF BADINI, tO MOVC,- "That leave be granted to move a resolution for the removal of Senator Muhammad Sadiq Sanjrani from the office of the Chairman, Senate of Pakistan." 2 RESOLUTION 3. SENATORS RAJA MUHAMMAD ZAFAR-UL-HAQ, LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION, ATTA UR REHMAN, MOLVI FAIZ MUHAMMAD, ABIDA MUHAMMAD AZEEMI AGHA SHAHZAIB DURRANI' RANA MAHMOOD UL HASSAN, PERVAIZ RASHEED, MUSADIK MASOOD MALIK, SITARA AYAZ, MUHAMMAD JAVED ABBASI, MUHAMMAD USMAN KHAN KAKAR, MIR KABEER AHMED MUHAMMAD SHAHI, MOLANA ABDUL GHAFOOR HAIDERT, MUHAMMAD TAHIR BIZINJO, MUSHAHID ULLAH KHAN, SALEEM ZI^^ MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI KHAN JUNEJO, GHOUS MUHAMMAD KHAN NIAZI, RIANA MAQBOOL AHMAD, DR. -

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017 Author: Muhammad Nafees Editor: Zeeshan Salahuddin Table of Contents Table of Contents ___________________________________ 3 Acronyms __________________________________________ 4 Executive Summary __________________________________ 6 Fatalities from Violence in Pakistan _____________________ 8 Victims of Violence in Pakistan________________________ 16 Fatalities of Civilians ................................................................ 16 Fatalities of Security Officials .................................................. 24 Fatalities of Militants, Insurgents and Criminals .................. 26 Nature and Methods of Violence Used _________________ 29 Key militants, criminals, politicians, foreign agents, and others arrested in 2017 ___________________________ 32 Regional Breakdown ________________________________ 33 Balochistan ................................................................................ 33 Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) ......................... 38 Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KP) ....................................................... 42 Punjab ........................................................................................ 47 Sindh .......................................................................................... 52 Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), Islamabad, and Gilgit Baltistan (GB) ............................................................................ 59 Sectarian Violence .................................................................... 59 3 © Center -

Tando Muhammad Khan

Tando Muhammad Khan 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010002 GBPS - YAR M. KANDRA@PIR BUX KANDRA Primary Boys 9,117 1,823 7,294 1,823 1,823 7,294 29,175 7,294 2 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010016 GBPS - YAR MUHAMMAD KANDRA Primary Boys 11,323 2,265 9,058 2,265 2,265 9,058 36,233 9,058 3 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010017 GBPS - KHUDA BUX GUMB Primary Boys 14,353 2,871 11,482 2,871 2,871 11,482 45,929 11,482 4 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010022 GBPS - ALAM KHAN TALPUR Primary Boys 44,542 8,908 35,634 8,908 8,908 35,634 142,535 35,634 5 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010025 GBPS - PALIO GHUMRANI Primary Boys 28,220 5,644 22,576 5,644 5,644 22,576 90,303 22,576 6 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010026 GBPS - KARIMABAD Primary Boys 28,690 5,738 22,952 5,738 5,738 22,952 91,808 22,952 7 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. -

Baloch Insurgency and Its Impact on CPEC Jaleel, Sabahat and Bibi, Nazia

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Baloch Insurgency and its impact on CPEC jaleel, Sabahat and Bibi, Nazia University of Engineering and technology, Taxila, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad 18 July 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/90135/ MPRA Paper No. 90135, posted 24 Nov 2018 17:28 UTC Baloch Insurgency and its impact on CPEC Sabahat Jaleel (Lecturer UET Taxila) & Nazia Bibi (Assistant Professor PIDE) Abstract CPEC, a significant development project, aims to connect Pakistan and China through highways, oil and gas pipelines, railways and an optical fiber link all the way from Gwadar to Xinjiang. Being the biggest venture in the bilateral ties of China-Pakistan, the project faces certain undermining factors. The research explores the lingering security concerns that surfaced due to the destabilizing and separatist efforts of the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) and Baloch Liberation Front (BLF). It also elaborates the Chinese concerns and Pakistan efforts to address these concerns while assuming the hypothesis that a secure and stable environment is necessary to reap the fruits of this mega project. The work also answers some innovative questions thus helpful for the students of Economics, Pakistan history, politics, Internal Relations, Foreign Policy and for those who intend to read about China-Pakistan and their joint ventures as CPEC. The main objective of the study to empirically analyses the response of Baloch community. Graphical and empirical methods have been adopted to describe and analyze the facts and figures related to the topic. The results clearly indicate that CPEC will face resistance from people of Balochistan, which will negatively affect the prospects of CPEC. -

Nutrition Profile-Qambar Shahdadkot

1 | P a g e District Nutrition Profile 1. Qambar Shahdadkot District Qambar Shahdadkot district, founded in 1713, comprises seven talukas (namely Warah, Qambar, Kubo Saeed Khan, Shahdadkot, Sujawal Junejo, Mir Khan and Nasirabad). The district has a total geographical area of 5,675 square kilometres1 and has Shahdadkot city as its capital. It shares a border with the districts of Jacobabad, Larkana and Dadu. The geographical position of the district is depicted below in Figure 1: Figure 1: Geographical Map of Qambar Shahdadkot District 2. Overall Development Situation in Qambar Shahdadkot District According to the 2013 Human Development Index (HDI), Qambar Shahdadkot is an underdeveloped district with a value of 0.35, which is lower than the gross HDI value of Sindh province (0.59). The index reflects a composite statistic used to rank life expectancy, education and per-capita Gross National Income in the area to judge the level of “human development” where Medium Human Development ranges from 0.555 to 0.699 and a rank below 0.555 signifies Low Human Development. When compared with the neighbouring districts, Qambar Shahdadkot appears to be in last place as shown in Figure 2 belowi. Qambar Shahdadkot and all of its neighbours are underdeveloped districts. 1 USAID/IMMAP Pakistan Emergency Situation Analysis - District Qambar Shahdadkot, August 2014 Page i 2 | P a g e District Nutrition Profile Qambar Shahdadkot District Human Development Index Rankings in Comparison to its Neighbours 0.45 0.4 0.4 0.35 Qambar Jacobabad Larkana Dadu Shahdadkot Figure 2: HDI Ranking of Qambar Shahdadkot District and its Neighbours 3. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity.