The Pendle Witches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

Pendle Sculpture Trail in an Atmospheric Woodland Setting

Walk distance: It is approximately 1 mile to get to the trail from Barley Car Park including one uphill stretch and one steep path. Once in Aitken Wood, which is situated on a slope, you could easily walk another mile walking around. Please wear stout footwear as there can be some muddy stretches after wet weather. Allow around 2 to 3 hours for your visit. See back cover for details on how to book a tramper vehicle for easier access to the wood for people with walking difficulties. Visit the Pendle Sculpture Trail in an atmospheric woodland setting. Art, history and nature come together against the stunning backdrop of Pendle Hill. Four artists have created a unique and intriguing range of sculptures. Their work is inspired by the history of the Pendle Witches of 1612 and the natural world in this wild and beautiful corner of Lancashire. A Witches Plaque Explore the peaceful setting of Aitken Wood to find ceramic plaques by Sarah McDade. She’s designed each one individually to symbolise the ten people from Pendle who were accused of witchcraft over 400 years ago. You’ll also find an inspiring range of sculptures, large and small, which are created from wood, steel and stone, including Philippe Handford’s amazing The Artists (as pictured here left to right) are Philippe Handford (Lead curving tree sculptures. Artist), Steve Blaylock, Martyn Bednarczuk, and Sarah McDade Philippe’s sculptures include: after dark. Reconnected 1, Reconnected had a religious vision on top There’s even a beautifully 2, The Gateway, Life Circle of nearby Pendle Hill which carved life-size figure of Philippe Handford, the lead kind of permanent trail. -

Barley and Black Moss a Fantastic Countryside Route, Offering Stunning Views of Pendle Hill

1 Barley and Black Moss A fantastic countryside route, offering stunning views of Pendle Hill START: The Barley Mow, Barley (GPS waypoint SD 821 404) DISTANCE: 6.5 miles (10.5km) DIFFICULTY: HEIGHT GAIN: APPROX. TIME: 2 hours 30 minutes PARKING: The Barley Mow or Barley car park ROUTE TERRAIN: Tarmac lanes, fields and moorland FACILITIES: Toilets and refreshments available in Barley SUITABILITY: Not suitable for wheelchairs or prams, dogs allowed but must be kept under control around livestock OS MAPS: Landranger 103 (Blackburn and Burnley), Explorer OL21 (South Pennines) David Turner LANCASHIRE WALKS BARLEY AND BLACK MOSS through agriculture and there is Downham, Barrowford and travelling from further afield, you evidence of a cattle farm being Nelson. For more times, visit can catch the train to Clitheroe established in the area around www.lancashire.gov.uk and from Manchester Victoria, which The walker’s view 1266. The village continued to search for the Clitheroe Local calls at Salford, Bolton, Blackburn earn its living through farming Services and Pendle Witch and Darwen, then catch the bus David Turner explores Pendle until the 18th century, when Hopper timetable. If you’re to Barley from there. on this route textiles were manufactured and I felt a pang of regret as I pulled into the car handlooms were installed in the park to begin this walk around the fields and lofts of many smallholdings, as moorland of Barley. Fancy turning up in the shadow of Pendle Hill an extra form of income. Where to visit and not climbing to the top! Unforgivable – or so I thought. -

The Magic of Britain

DISCOVER BRITAIN WITH BRITAIN’S BEST GUIDES GUIDEthe WINTER 2016 THE MAGIC OF BRITAIN The spellbinding history of druids, wizards and witches INSIDE SEVEN TALL TALES – LEGENDS, LIES AND LORE OUR GUIDES’ GUIDE TO NORTHERN IRELAND AND HAMPSHIRE GOING UNDERGROUND WITH THE ROYAL MAIL’S SECRET RAILWAY From Bollywood A CHILD’S EYE VIEW A HULL OF A TIME to St John’s Wood Landscapes from children’s literature Getting naked in the City of Culture THE EVENT #1 ATTRACTIONS | DESTINATIONS | HOTELS Over 2 days, explore the very best hotels, JOIN US AT attractions and destinations from the length and THE ESSENTIAL breadth of the British Isles. Offering a great opportunity to meet existing and source new EXHIBITION DEDICATED suppliers and service providers, your visit will leave TO YOUR INDUSTRY you packed up and ready to go for your next trip! Book your FREE trade ticket quoting Priority Code BTTS105 at WWW.TOURISMSHOW.CO.UK 2 Contents 4 What to see this winter Go underground with Mail Rail; a 600 year wait to visit London’s Charterhouse; burial barrows make a comeback 6 The Guides’ Guide From giants to monsters, our guides reveal their top ten places to visit in Northern Ireland 8 The Magic of Britain Mark King, Chair to the The spellbinding history of druids, witches and wizards British Guild of Tourist Guides and the spells they cast on us to this day A WARM WELCOME 14 Legends, Lies and Lore Fact and fiction from British history TO ‘THE GUIDE’... During these long, dark nights, it’s fitting to 16 A Child’s Eye view of Britain feature two themes that many guides talk about The landscapes and locations that inspired in their tours: children’s literature and witchcraft. -

Witches Road Trail

DIRECTIONS from Pendle Lancaster Follow the Tourism Signs • The starting point for the Pendle Witch Trail is at Pendle The Year The Trail Heritage Centre, in Barrowford near Nelson. • Follow the A682 out of Barrowford to Blacko. Jubilee Tower Turn left at the sign to Roughlee. r oo M e • At the crossroads carry straight on to Newchurch. grass M it High oo h r W • Turn right past Witches Galore, go up the hill. T rou Emmets gh of • Keep straight on through Barley Village past the Pendle The Pendle Witches lived at Bow 1612 land Inn, the road bends sharp left to Downham. Sykes a turbulent time in England’s Dunsop Bridge • Go past the Assheton Arms and follow the road to the left, history. It was an era of and keep left. • Turn left to Clitheroe following the A671. ill Moor religious persecution and H l M a r superstition. Newton • Follow signs for the Castle & Museum and take time to Waddington explore this historic market town. Whalley Abbey is just 4 Chatburn miles from Clitheroe and makes a worthwhile diversion. Then take the B6478 to Waddington and the Trough of Newchurch Downham Bowland. Roughlee James I was King and he lived Barrowford • Follow signs to Newton, past the Parker Arms (B6478). in fear of rebellion. He had • In Newton Village turn left to Dunsop Bridge. Clitheroe survived the Gunpowder Plot of Pendle • Go through Dunsop Bridge then turn right to the Trough H il Colne l of Bowland and Lancaster. 1605 where the Catholic plotters Nelson • Follow signs to Lancaster. -

Criminals, Lunatics and Witches: Finding the Less Than Pleasant in Family History Craig L

Criminals, Lunatics and Witches: Finding the Less Than Pleasant in Family History Craig L. Foster AG® Criminals The largest portion of the known criminal population were the common sneak thieves which included burglars, pickpockets and other types of thieves. Those involved in more violent crimes such as assault, battery, violent theft, highway robbery, manslaughter, murder, rape and other sexual offenses were fewer in number. Henry Mayhew, et al., The London Underworld in the Victorian Period (Minealoa, New York: Dover Publications, 2005), 109. In 1857, at least 8,600 prostitutes were known to London authorities. Incredibly, that was just a small portion of the estimated prostitutes in London. While London had the most prostitutes, there were ladies of ill-repute in every industrial centre and most market towns. Henry Mayhew, et al., The London Underworld in the Victorian Period (Minealoa, New York: Dover Publications, 2005), 6. Lists/records of “disorderly women” are found at: The National Archives at Kew Bristol Archives Dorset History Centre Gloucestershire Archives Plymouth & West Devon Records As well as many other repositories Children also served time in prison. For example, in Dublin, Ireland alone, between 1859 and 1891, 12,671 children between ages seven and sixteen were imprisoned. Prison registers are found at the National Archives of Ireland. Aoife O’Conner, “Child Prisoners,” Irish Lives Remembered 36 (Spring 2017), [n.p.] Online Sources for Searching for Criminals: Ancestry Birmingham, England, Calendars of Prisoners, 1854-1904 Cornwall, England, Bodmin Gaol, 1821-1899 Dorset, England, Calendar of Prisoners, 1854-1904 England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 London, England, King’s Bench and Fleet Prison Discharge Books and Prisoner Lists, 1734-1862 Surrey, England, Calendar of Prisoners, 1880-1891, 1906-1913 United Kingdom, Licenses of Parole for Female Convicts, 1853-1871, 1883-1887 FamilySearch Ireland Prison Registers, 1790-1924 findmypast Britain, Newgate Prison Calendar, vols. -

The Witches of Selwood Forest

The Witches of Selwood Forest The Witches of Selwood Forest: Witchcraft and Demonism in the West of England, 1625-1700 By Andrew Pickering The Witches of Selwood Forest: Witchcraft and Demonism in the West of England, 1625-1700 By Andrew Pickering This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Andrew Pickering All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5188-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5188-6 [In] other cases, when wicked or mistaken people charge us with crimes of which we are not guilty, we clear ourselves by showing that at that time we were at home, or in some other place, about our honest business; but in prosecutions for witchcraft, that most natural and just defence is a mere jest, for if any cracked-brain girl imagines (or any lying spirit makes her believe) that she sees any old woman, or other person pursuing her in her visions, the defenders of the vulgar witchcraft […] hang the accused parties for things they were doing when they were, perhaps, asleep on their beds or saying their prayers —Francis Hutchinson, An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft (1718), vi-vii. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations, Maps and Tables .................................................. -

Saturday 10Th to Sunday 18Th August 57 Guided Walks in Some of Lancashire’S Most Beautiful Countryside, from the Easy to the Challenging

Saturday 10th to Sunday 18th August 57 guided walks in some of Lancashire’s most beautiful countryside, from the easy to the challenging. Walking Festival A5 booklet 2019 2 09/05/2019 16:18 Pendle Walking Festival 2019 © Photography by Alastair Lee, Lee Johnson, Steve Bradley and Neil McGowan. Packhorse bridge and Wycoller Hall Walking Festival A5 booklet 2019 3 09/05/2019 16:19 Key to symbols Packed lunch Please bring a packed lunch. Country Pub We will visit one of our country pubs for a refreshment break during the walk. Cafe We will stop at a cafe for light refreshments during the walk. Family Friendly Walks These walks will include games, stories or “treasure” hunts to help children engage with the natural world and local history. Dogs welcome Well behaved dogs on leads are welcome. Dogs are not allowed on walks not showing this symbol. Booking essential Booking on these walks via www. visitpendle.com is essential. See further information on page 3. Up and Active Walks These walks are included in a programme of walks which take place throughout the year. There is no need to book if you are a regular Up and Active walker. To find out more about Up and Active Walks in Pendle please visit www. upandactive.co.uk Welcome to one of the UK’s largest walking festivals! The annual Pendle Walking Festival has put the area firmly on the map. It’s a fantastic place to walk and enjoy some Follow us on facebook of the most stunning countryside views in the Follow us or Tweet us @VisitPendle north of England. -

PENDLE HILL LANDSCAPE PARTNERSHIP LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT PART 2: Landscape Character Types

PENDLE HILL LANDSCAPE PARTNERSHIP LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT PART 2: Landscape Character Types 1 | P a g e Report commissioned by Lancashire County Council with financial support from the Heritage Lottery Fund. Carried out by Robin Gray Chartered Member of the Landscape Institute. Based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution of civil proceedings. Lancashire County Council. Licence Number: 100023320. Forest of Bowland AONB The Stables 4 Root Hill Estate Yard Whitewell Road Dunsop Bridge Clitheroe Lancashire BB7 3AY Email: [email protected] Web: www.forestofbowland.com 2 | P a g e CONTENTS 4.0 Landscape Character Types 4 A Moorland Plateaux 6 B.Unenclosed Mooorland Hills 11 C.Enclosed Moorland Hills 18 D.Moorland Fringe 28 E.Undulating Lowland 44 G.Undulating lowland farmland with parkland 58 M.Forestry and reservoir 70 N.Farmed ridges 75 O.Industrial foothills and valleys 80 5.0 Proposals 87 6.0 References 90 Appendix 1: Where to draw the boundary: a sense of place 92 Appendix 2: Map#7: Scheduled Ancient Monuments 93 Appendix 3: Views from Pendle Hill 94 3 | P a g e 4.0 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER TYPES Within the immediate environment of Pendle Hill are a number of varied landscapes that encompass remote moorland plateaux, pasture bounded by hedges or moorland fringe. These are represented by a number of landscape types (map#6) which are described in section 4 below. Each generic landscape type has a distinct character with similar physical influences (underlying geology, land form, pedology) and indeed a common history of land management such as the enclosure of moorland edges to create ‘in-bye land’. -

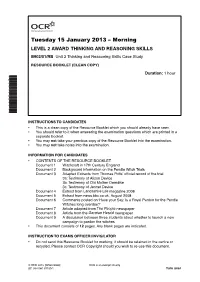

Tuesday 15 January 2013 – Morning LEVEL 2 AWARD THINKING and REASONING SKILLS B902/01/RB Unit 2 Thinking and Reasoning Skills Case Study

Tuesday 15 January 2013 – Morning LEVEL 2 AWARD THINKING AND REASONING SKILLS B902/01/RB Unit 2 Thinking and Reasoning Skills Case Study RESOURCE BOOKLET (CLEAN COPY) Duration: 1 hour *B922100113* INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES • This is a clean copy of the Resource Booklet which you should already have seen. • You should refer to it when answering the examination questions which are printed in a separate booklet. • You may not take your previous copy of the Resource Booklet into the examination. • You may not take notes into the examination. INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES • CONTENTS OF THE RESOURCE BOOKLET Document 1 Witchcraft in 17th Century England Document 2 Background information on the Pendle Witch Trials Document 3 Adapted Extracts from Thomas Potts’ official record of the trial 3a: Testimony of Alizon Device 3b: Testimony of Old Mother Demdike 3c: Testimony of Jennet Device Document 4 Extract from Lancashire Life magazine 2008 Document 5 Extract from news.bbc.co.uk, August 2008 Document 6 Comments posted on ‘Have your Say: Is a Royal Pardon for the Pendle Witches long overdue?’ Document 7 Article adapted from The People newspaper Document 8 Article from the German Herald newspaper Document 9 A discussion between three students about whether to launch a new campaign to pardon the witches • This document consists of 12 pages. Any blank pages are indicated. INSTRUCTION TO EXAMS OFFICER / INVIGILATOR • Do not send this Resource Booklet for marking; it should be retained in the centre or recycled. Please contact OCR Copyright should you wish to re-use this document. © OCR 2013 [D/502/0968] OCR is an exempt Charity DC (NF/SW) 67159/1 Turn over 2 DOCUMENT 1 Witchcraft in 17th Century England • Witchcraft, along with refusing to attend church, was a crime in 1612. -

FULL PRICE LIST + COSTS Product Product Unit Code Description

FULL PRICE LIST + COSTS Product Product Unit Code Description Desc BEER - DRAUGHT CASK MOOR0005 MOORHOUSES PRIDE OF PENDLE(4.1%) 9GALL MOOR0010 MOORHOUSES WHITE WITCH (3.9%) 9GALL MOOR0020 MOORHOUSES BLOND WITCH (4.5%) 9GALL MOOR0025 MOORHOUSES PREMIER BITTER (3.7%) 9GALL MOOR0035 MOORHOUSES PENDLE WITCHES (5.1%) 9GALL BLAC0005 BLACK SHEEP B/BITTER - 3.8% (9G) 9GALL BLAC0010 BLACK SHEEP SPEC ALE - 4.4% (9G) 9GALL JENN0005 JENNINGS CUMBERLAND ALE -4% (9G) 9GALL MARS0004 MARSTONS EPA -"FAST CASK" (3.6%) 9GALL MARSTONS9(C) MARSTONS PEDIGREE "FAST CASK" 9G 9GALL THWA0001 THWAITES ORIGINAL - 3.6% (9GALL) 9GALL THWA0005 THWAITES LANCASTER BOMBER - 4.4% 9GALL THWA0020 WAINWRIGHTS - 4.1% (9G) 9GALL THWA0020A (18 GALL) - WAINWRIGHTS - 4.1% 18GALL WELL0005 WELLS BOMBARDIER AMBER CASK (9G) 9GALL WYCH0001 WYCHWOOD HOBGOBLIN 4.5% (40.9L) 9GALL WYCH0002 "GOLD" - HOBGOBLIN (4.2%) 9GALL TAYL0001 T.TAYLORS LANDLORD - 4.3% (9G) 9GALL TAYL0002 T.TAYLORS LANDLORD - 4.3% (18G) 18GALL TAYL0005 T.TAYLORS GOLDEN BEST - (3.5%) 9GALL TAYL0006 T.TAYLORS BOLTMAKERS - (4.0%) 9GALL TAYL0006A T.TAYLOR BOLTMAKER - 4.0% (18G) 18GALL TAYL0007 T.TAYLORS RAM TAM - (4.3%) 9GALL TAYL0008 T.TAYLORS DARK MILD - (3.5%) 9GALL TAYL0009 T.TAYLORS KNOWLE SPRING 4.2% (9G 9GALL ROBI0010 ROBINSONS WIZARD 9G (3.7%) 9GALL ROBI0014 ROBINSONS TROOPER 4.8% (9GALL) 9GALL ROBI0020 ROBINSONS DIZZY BLONDE (9G) 9GALL ROBI0021 ROBINSONS UNICORN 4.2% 9GALL BASSCASK10 BASS CASK (10GALL) 4.4% 10GALL BOXSTEAM01 BOX STEAM GOLDEN BOLT (9GALL) 9GALL BOXSTEAM02 BOX STEAM SOUL TRAIN (9GALL) 9GALL BOXSTEAM03 -

Saturday 13Th August to Sunday 21St August 71 Guided Walks in Some of Lancashire’S Most Beautiful Countryside, from the Easy to the Challenging

FREE PROGRAMME Includes Family Friendly Walks Saturday 13th August to Sunday 21st August 71 guided walks in some of Lancashire’s most beautiful countryside, from the easy to the challenging. key to symbols Dogs welcome Well behaved dogs on leads are welcome. Dogs are Bewitching, not allowed on walks not showing this symbol. Country pubs or cafés These walks will visit one boats and of our country pubs or a café for a short refreshment At Whalley Warm & Dry we understand the importance of properly fitted, break during or after the supportive footwear and its impact on the comfort of your feet and the enjoyment walk. of your walk. Customers travel from across the country to take advantage of our Brontës… Lunch stop No need to bring your award-winning specialist fitting service and years of experience... sarnies! We will stop at a Welcome to one of the UK’s pub or café for a light meal largest walking festivals! during or after the walk. History walks The annual Pendle Walking Festival These walks focus on the has put the area firmly on the map. history of the area. Pushchair friendly It’s a fantastic place to walk and These walks follow stile-free enjoy some of the most stunning paths and are suitable for robust pushchairs. countryside views in the whole of Packed lunch Lancashire. Please bring a packed lunch. Booking essential 1. WE MEASURE 2. WE ANALYSE To book a place on these Specially trained fitters take ten We interpret the measurements walks please use our online booking system provided by measurements to identify your and identify the foot type and www.eventbrite.co.uk.