The Witches of Selwood Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

67 Nunney Road, Frome, Somerset BA11 4LE £550,000

67 Nunney Road, Frome, Somerset BA11 4LE £550,000 Description It has thriving arts and vibrant music communities. An opportunity to purchase a unique town property built Private schools are to be found in Wells, Bath, by the current family in 1960. The property was ahead of Warminster, Cranmore, Beckington, Glastonbury and its time at point of construction and remains both Street. Bath and Bristol are within commuting distance, individual and contemporary to this day. Interesting and the local railway station connects at Westbury for features include the kitchen with a polished concrete London, Paddington. The property is within easy walking work surface and a pi llar ed canopy running the width of distance of shops, cafés, and amenities. the property to the rear. There is an extensive garden to the front and a very large garden to the rear. This is a Services property that really is a once in a lifetime opportunity. 3 Mains drainage, water, electricity, BT are all connected. The Accommodation The property provides an entrance hallway with four Heating bedrooms set off (please note one bedroom is a walk- Gas fired central heating. through room - this might work well as a study or snug). There are two bathrooms, a WC and an open plan living/dining room. The kitchen has a polished concrete Council Tax Band work surface with matching pillars. The property remains Council Tax Band ‘C’. very much as it was built and may require sympathetic updating. T o one side is the garage which could, EPC Rating perhaps, be converted to provide extra living Rating ‘C’. -

Aug-Nov 2019

SOUTH SOMERSET GROUP www.somersetramblers.co.uk A local group of the Ramblers’ Association. Registered. Charity No.1093577. Promoting rambling, protecting rights of way, campaigning for access to open country and defending the beauty of the countryside. AUG 2019 - NOV 2019 WALKS New walk leaders should contact the appropriate programme secretary. If you would like help in organising your walk, please contact any committee member who will be able to assist. Walk leaders and back-markers should exchange mobile phone numbers so that contact can be maintained in cases of emergency. Leaders and back-markers without phones should appoint substitutes. Numbers should be exchanged at the start of the walk. Every effort should be made to ensure a first-aid kit is available on all walks.. Walks are graded according to the following classification of pace:- A = Fast B = Brisk C = 5-7 miles Medium pace D = generally 4-5 miles at a more moderate pace Starting times of walks vary and need to be noted carefully. Members should ensure they carry their membership cards on all walks. NOTICES Annual General Meeting The Committee would welcome your presence on Saturday 3rd Nov at East Coker Village Hall 2.00 pm to meet with other members in reviewing the past year and planning for the future.. Motions and other items should be sent to the secretary by 16th October. Group Committee Meeting: will be held on Thu Oct 3rd 2019. Programme Distribution. Short walk distribution is on 7th November and Medium walk distribution is on 14th November. Christmas Lunch. This will be held at 1.00pm on Thursday 12th December at the Muddled Man, West Chinnock. -

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

The Physician and Witchcraft in Restoration England

THE PHYSICIAN AND WITCHCRAFT IN RESTORATION ENGLAND by GARFIELD TOURNEY THE YEAR of 1660 witnessed important political and scientific developments in England. The restoration of the monarchy and the Church of England occurred with the return of Charles II after the dissolution of the Commonwealth and the Puritan influence. The Royal Society, after informal meetings for nearly fifteen years, was established as a scientific organization in 1660 and received its Royal Charter in 1662. During the English revolution, and for a short time during the Commonwealth, interest in witchcraft mounted. Between 1645 and 1646 Matthew Hopkins acquired the reputation as the most notorious witch-finder in the history of England.I His activities in Essex and the other eastern counties led to the execution of as many as 200 witches. In Suffolk it is estimated that he was responsible for arresting at least 124 persons for witchcraft, of whom 68 were hanged. The excesses soon led to a reaction and Hopkins lost his influence, and died shortly thereafter in 1646. There then was a continuing decline in witchcraft persecutions, and an increasing scepticism toward the phenomena of witchcraft was expressed. Scepticism was best exemplified in Thomas Hobbes' (1588-1679) Leviathan, published in 1651.2 Hobbes presented a materialistic philosophy, emphasizing change occurring in motion, the material nature of mental activity, the elimination of final causes, and the rejection of the reality of spirit. He decried the belief in witchcraft and the supematural, emphasizing -

SCUDAMORE FAMILIES of WELLOW, BATH and FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440

Skydmore/ Scudamore Families of Wellow, Bath & Frome, Somerset, from 1440 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKYDMORE/ SCUDAMORE FAMILIES OF WELLOW, BATH AND FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440. edited by Linda Moffatt ©2016, from the original work of Warren Skidmore. Revised July 2017. Preface I have combined work by Warren Skidmore from two sources in the production of this paper. Much of the content was originally published in book form as part of Thirty Generations of The Scudamore/Skidmore Family in England and America by Warren Skidmore, and revised and sold on CD in 2006. The material from this CD has now been transferred to the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com. Warren Skidmore produced in 2013 his Occasional Paper No. 46 Scudamore Descendants of certain Younger Sons that came out of Upton Scudamore, Wiltshire. In this paper he sets out the considerable circumstantial evidence for the origin of the Scudamores later found at Wellow, Somerset, as being Bratton Clovelly, Devon. Interested readers should consult in particular Section 5 of this, Warren’s last Occasional Paper, at the same website. The original text used by Warren Skidmore has been retained here, apart from the following. • Code numbers have been assigned to each male head of household, allowing cross-reference to other information in the databases of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study. Male heads of household in this piece have a code number prefixed WLW to denote their origin at Wellow. • In line with the policy of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study, details of individuals born within approximately the last 100 years are not placed on the Internet without express permission of descendants. -

SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS 2016 17 SEPTEMBER - 2 OCTOBER SOS GUIDE 2016 COVER Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 2

SOS_GUIDE_2016_COVER_Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 1 SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS 2016 17 SEPTEMBER - 2 OCTOBER SOS_GUIDE_2016_COVER_Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 2 Somerset Open Studios is a much-loved and thriving event and I’m proud to support it. It plays an invaluable role in identifying and celebrating a huge variety of creative activities and projects in this county, finding emerging artists and raising awareness of them. I urge you to go out and enjoy these glorious weeks of cultural exploration. Kevin McCloud Photo: Glenn Dearing “What a fantastic creative county we all live in!” Michael Eavis www.somersetartworks.org.uk SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS #SomersetOpenStudios16 SOS_GUIDE_2016_SB[2]_saw_guide 11/07/2016 09:58 Page 1 WELCOME TO OUR FESTIVAL! About Somerset Art Works Somerset Open Studios is back again! This year we have 208 venues and nearly 300 artists participating, Placing art at the heart of Somerset, showing a huge variety of work. Artists from every investing in the arts community, enriching lives. background and discipline will open up their studios - places that are usually private working environments, SAW is an artist-led organisation and what a privilege to be allowed in! Somerset’s only countywide agency dedicated to developing visual arts, Each year, Somerset Open Studios also works with weaving together communities and individuals, organisations and schools to develop the supporting the artists who enrich our event. We are delighted to work with King’s School lives. We want Somerset to be a Bruton and Bruton School for Girls to offer new and place where people expect to exciting work from a growing generation of artistic engage with excellent visual art that talent. -

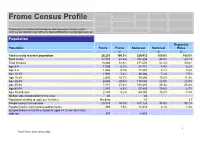

Frome Census Profile

Frome Census Profile Produced by the Partnership Intelligence Unit, Somerset County Council 2011 Census statistics from Office for National Statistics [email protected] Population England & Population Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % Total usually resident population 26,203 100.0% 529,972 100.0% 100.0% Total males 12,739 48.6% 258,396 48.8% 49.2% Total females 13,464 51.4% 271,576 51.2% 50.8% Age 0-4 1,659 6.3% 28,717 5.4% 6.2% Age 5-9 1,543 5.9% 27,487 5.2% 5.6% Age 10-15 1,936 7.4% 38,386 7.2% 7.0% Age 16-24 2,805 10.7% 54,266 10.2% 11.9% Age 25-44 6,685 25.5% 119,246 22.5% 27.4% Age 45-64 7,171 27.4% 150,210 28.3% 25.4% Age 65-74 2,247 8.6% 57,463 10.8% 8.7% Age 75 and over 2,157 8.2% 54,197 10.2% 7.8% Median age of population in the area 40 44 Population density (people per hectare) No data 1.5 3.7 People living in households 25,814 98.5% 517,124 97.6% 98.2% People living in communal establishments 389 1.5% 12,848 2.4% 1.8% Schoolchildren or full-time students aged 4+ at non term-time address 307 8,053 1 Frome Facts: 2011 census data Identity England & Ethnic Group Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % White Total 25,625 97.8% 519,255 98.0% 86.0% White: English/Welsh/Scottish/ Northern Irish/British 24,557 93.7% 501,558 94.6% 80.5% White: Irish 142 0.5% 2,257 0.4% 0.9% White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller 91 0.3% 733 0.1% 0.1% White: Other White 835 3.2% 14,707 2.8% 4.4% Black and Minority Ethnic Total 578 2.2% 10,717 2.0% 14.0% Mixed: White and Black Caribbean 57 0.2% 1,200 0.2% 0.8% Mixed: White and Black African 45 0.2% -

Saints, Monks and Bishops; Cult and Authority in the Diocese of Wells (England) Before the Norman Conquest

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 2 63-95 2011 Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen University of Bristol Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Costen, Michael. "Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 2 (2011): 63-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Costen Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen, University of Bristol, UK Introduction This paper is founded upon a database, assembled by the writer, of some 3300 instances of dedications to saints and of other cult objects in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. The database makes it possible to order references to an object in many ways including in terms of dedication, location, date, and possible authenticity, and it makes data available to derive some history of the object in order to assess the reliability of the information it presents. -

BUNYAN STUDIES a Journal of Reformation and Nonconformist Culture

BUNYAN STUDIES A Journal of Reformation and Nonconformist Culture Number 23 2019 Bunyan Studies is the official journal of The International John Bunyan Society www.johnbunyansociety.org www.northumbria.ac.uk/bunyanstudies BUNYAN STUDIES –— A Journal of Reformation and Nonconformist Culture –— Editors W. R. Owens, Open University and University of Bedfordshire Stuart Sim, formerly of Northumbria University David Walker, Northumbria University Associate Editors Rachel Adcock, Keele University Robert W. Daniel, University of Warwick Reviews Editor David Parry, University of Exeter Editorial Advisory Board Sylvia Brown, University of Alberta N. H. Keeble, University of Stirling Vera J. Camden, Kent State University Thomas H. Luxon, Dartmouth College Anne Dunan-Page, Aix-Marseille Université Vincent Newey, University of Leicester Katsuhiro Engetsu, Doshisha University Roger Pooley, Keele University Isabel Hofmeyr, University of the Witwatersrand Nigel Smith, Princeton University Ann Hughes, Keele University Richard Terry, Northumbria University Editorial contributions and correspondence should be sent by email to W. R. Owens at: [email protected] Books for review and reviews should be sent by mail or email to: Dr David Parry, Department of English and Film, University of Exeter, Queen’s Building, The Queen’s Drive, Exeter EX4 4QH, UK [email protected] Subscriptions: Please see Subscription Form at the back for further details. Bunyan Studies is free to members of the International John Bunyan Society (see Membership Form at the back). Subscription charges for non-members are as follows: Within the UK, each issue (including postage) is £10.00 for individuals; £20.00 for institutions. Outside the UK, each issue (including airmail postage) is £12.00/US$20.00 for individuals; £24.00/US$40.00 for institutions. -

Henry More, Richard Baxter, and Francis Glisson's Trea Tise on the Energetic Na Ture of Substance

Medical History, 1987, 31: 15-40. MEDICINE AND PNEUMATOLOGY: HENRY MORE, RICHARD BAXTER, AND FRANCIS GLISSON'S TREA TISE ON THE ENERGETIC NA TURE OF SUBSTANCE by JOHN HENRY* The nature of the soul and its relationship to the body has always proved problematical for Christian philosophy. The source ofthe difficulty can be traced back to the efforts of the early Fathers to reconcile the essentially pagan concept of an immaterial and immortal soul with apostolic teachings about the after-life in which all the emphasis is placed upon the resurrection of the body. The tensions between these two traditions inevitably became strained during the sixteenth century when Protestant reformers insisted on a closer adherence to Scripture. Furthermore, even when leaving the problems of Scriptural hermeneutics aside, the dualistic approach to the question, in which soul (or spirit) and body are held to be categorically different in essence, had to overcome a number of intractable philosophical problems. So, it was not simply coincidence that when the new mechanical philosophy began to be formulated in a systematic way in the seventeenth century, it was couched in vigorously dualistic terms. In fact, three of the earliest fully elaborated systems of mechanical philosophy, those of Descartes, Digby, and Charleton, were explicitly intended to provide a philosophical prop for dualist theology.' Moreover, it was because of its usefulness in promoting dualism that Cartesianism was first popularized in England not by a natural philosopher but by the Cambridge Platonist and theologian, Henry More.2 *John Henry, MPhil, PhD, Wellcome Institute for the History ofMedicine, 183 Euston Road, London NWI 2BP. -

The 'Great' Battle of the Croscombe Cross and My Village Ancestry

The ‘Great’ Battle of the Croscombe Cross and my village ancestry By Mark Wareham Updated 26th August 2013 In the late 19th century there was an uprising over the preservation of the medieval cross in the village of Croscombe in Somerset. This incident was as a result of efforts by the authorities to destroy the ancient monument and I was delighted to discover that a couple of my ancestors and other family members were directly involved and that one of them was one of the ringleaders. This is a brief story of the skirmish with same notes on the Say, Carver and Marshman families of the Croscombe. I shall start with descriptions of the ‘battle’ from two authors. From ‘Old Crosses of Somerset, 1877, by C Pooley’ “Some years ago, an incident of no little importance occurred in connection with this Cross, which deserves to be recorded. The local way-wardens, thinking the Cross an incumbrance, endeavoured to remove it. It seems that the removal of so ancient a landmark in historical associations of the village proved a graver and more serious matter than these enlightened wardens of the way were aware of. The inhabitants gathered around the old Cross, and came to its defence with bold and determined hearts, bent upon its preservation, but not before the shaft had been hurled to the ground, and its finial broken in twain. The demolishing party having been driven off, a flag was hoisted by the brave villagers bearing upon it the legend ‘BE FAITHFUL;’ this was struck during the melee but as quickly regained, and the standard of the Cross again waived proudly over the heads of the loyal and Christian defenders.