Accountability and Abuses of Power in World Politics RUTH W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016 Professor: Office: Office Phone: Office Hours: Email: Course Description and Learning Outcomes Comparative politics is perhaps the broadest field of political science. This course will introduce students to the major theoretical approaches employed in comparative politics. The major debates and controversies in the field will be examined. Although some associate comparative politics with “the comparative method,” those conducting research in the area of comparative politics use a multitude of methodologies and pursue diverse topics. In this course, students will analyze and discuss the theoretical approaches and methods used in comparative politics. Course Requirements Class participation and attendance. Students must come to class prepared, having completed all of the required reading, and ready to actively discuss the material at hand. Each student must submit comments/questions on the assigned readings for six classes (not including the class you help facilitate). Please e-mail them to me by noon on the day of class. Students are expected to attend each class. Missing classes will have a deleterious effect on this portion of the grade. Arriving late, leaving early, or interrupting class with a phone or other electronic device will also result in a drop in the student’s grade. Students are not allowed to sleep, read newspapers or anything else, listen to headphones, TEXT, or talk to others during class. You must turn off all electronic devices during class. Any exceptions must be cleared with me in advance. Laptop computers and iPads are allowed for taking notes ONLY. I reserve the right to ban laptops, iPads, and so forth. -

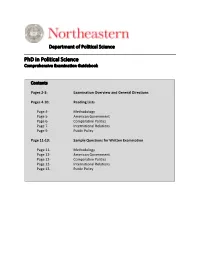

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Toward a More Democratic Congress?

TOWARD A MORE DEMOCRATIC CONGRESS? OUR IMPERFECT DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTION: THE CRITICS EXAMINED STEPHEN MACEDO* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 609 I. SENATE MALAPPORTIONMENT AND POLITICAL EQUALITY................. 611 II. IN DEFENSE OF THE SENATE................................................................ 618 III. CONSENT AS A DEMOCRATIC VIRTUE ................................................. 620 IV. REDISTRICTING AND THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE REFORM? ................ 620 V. THE PROBLEM OF GRIDLOCK, MINORITY VETOES, AND STATUS- QUO BIAS: UNCLOGGING THE CHANNELS OF POLITICAL CHANGE?.... 622 CONCLUSION................................................................................................... 627 INTRODUCTION There is much to admire in the work of those recent scholars of constitutional reform – including Sanford Levinson, Larry Sabato, and prior to them, Robert Dahl – who propose to reinvigorate our democracy by “correcting” and “revitalizing” our Constitution. They are right to warn that “Constitution worship” should not supplant critical thinking and sober assessment. There is no doubt that our 220-year-old founding charter – itself the product of compromise and consensus, and not only scholarly musing – could be improved upon. Dahl points out that in 1787, “[h]istory had produced no truly relevant models of representative government on the scale the United States had already attained, not to mention the scale it would reach in years to come.”1 Political science has since progressed; as Dahl also observes, none of us “would hire an electrician equipped only with Franklin’s knowledge to do our wiring.”2 But our political plumbing is just as archaic. I, too, have participated in efforts to assess the state of our democracy, and co-authored a work that offers recommendations, some of which overlap with * Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Politics and the University Center for Human Values; Director of the University Center for Human Values, Princeton University. -

Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar

The Profession ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar Michael Peress, SUNY–Stony Brook ABSTRACT This article develops a number of measures of the research productivity of politi- cal science departments using data collected from Google Scholar. Departments are ranked in terms of citations to articles published by faculty, citations to articles recently published by faculty, impact factors of journals in which faculty published, and number of top pub- lications in which faculty published. Results are presented in aggregate terms and on a per-faculty basis. he most widely used measure of the quality of of search results, from which I identified publications authored political science departments is the US News and by that faculty member, the journal in which the publication World Report ranking. It is based on a survey sent appeared (if applicable), and the number of citations to that to political science department heads and direc- article or book. tors of graduate studies. Respondents are asked to I constructed four measures for each faculty member. First, Trate other political science departments on a 1-to-5 scale; their I calculated the total number of citations. This can be -

Achieving Cooperating Under Anarchy,” by Robert Axelrod and Robert Keohane, 1985

Devarati Ghosh “Achieving Cooperating Under Anarchy,” by Robert Axelrod and Robert Keohane, 1985 · Definitions: remember that for cooperation to occur, there must be some combination of conflicting and shared interests. Cooperation is distinct from harmony, where there is a total identity of interests between states. Anarchy is the absence of common world government, but it does not imply that the world is devoid of organizational forms. · Three dimensions of structure impact the incentives for states to cooperate: the mutuality of interests, the shadow of the future, and the number of players. The mutuality of interests—is determined by an objective structure of material payoffs, as well as upon actors’ perceptions of that structure. Changes in beliefs about other players, as well as about the most optimal policy, may cause state leaders to prefer unilateral action. This is true of both political-economic and security issues. · The longer the shadow of the future, the more the costs of defection offset the short-term incentive to defect. This is more true of political-economic issues, where there is a greater likelihood of extended interaction, than of security issues, where a successful preemptive war would seriously advantage one of the players. Also important is the ability of states to identifying defection, which Axelrod and Keohane believe does not distinguish political-economic issues from security ones. · Once defection has been identified, the next problem is sanctioning the cheater. This becomes significantly more difficult when there is a large number of actors. Defection can be costly, so there must be enough incentive for states to punish defectors. -

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010 Gary King, Robert Putnam, and Sidney Verba Thursdays 12-2pm, Littauer M-17 Gary King [email protected], http://GKing.Harvard.edu Phone: 617-495-2027 Office: 34 Kirkland Street Robert Putnam [email protected] Phone: 617-495-0539 Office: 79 JFK Street, T376 Sidney Verba [email protected] Phone: 617-495-4421 Office: Littauer Center, M18 Prerequisite or corequisite: Gov1000 Overview If you could learn only one thing in graduate school, it should be how to do scholarly research. You should be able to assess the state of a scholarly literature, identify interesting questions, formulate strategies for answering them, have the methodological tools with which to conduct the research, and understand how to write up the results so they can be published. Although most graduate level courses address these issues indirectly, we provide an explicit analysis of each. We do this in the context of a variety of strategies of empirical political inquiry. Our examples cover American politics, international relations, compara- tive politics, and other subfields of political science that rely on empirical evidence. We do not address certain research in political theory for which empirical evidence is not central, but our methodological emphases will be as varied as our substantive examples. We take empirical evidence to be historical, quantitative, or anthropological. Specific methodolo- gies include survey research, experiments, non-experiments, intensive interviews, statistical analyses, case studies, and participant observation. Assignments Weekly reading assignments are listed below. Since our classes are largely participatory, be sure to complete the readings prior to the class for which they are as- signed. -

Robert O. Keohane: the Study of International Relations*

Robert O. Keohane: The Study of International Relations* Peter A. Gourevitch, University of California, San Diego n electing Robert Keohane APSA I president, members have made an interesting intellectual statement about the study of international rela- tions. Keohane has been the major theoretical challenger in the past quarter century of a previous Asso- ciation president, Kenneth Waltz, whose work dominated the debates in the field for many years. Keo- hane's writings, his debate with Waltz, his ideas about institutions, cooperation under anarchy, transna- tional relations, complex interdepen- dence, ideas, and domestic politics now stand as fundamental reference points for current discussions in this field.1 Theorizing, methodology, exten- sion, and integration: these nouns make a start of characterizing the Robert O. Keohane contributions Robert Keohane has made to the study of international relations. Methodology —Keohane places concepts, techniques, and ap- Theorizing— Keohane challenges the study of the strategic interac- proaches as the broader discpline. the realist analysis that anarchy tion among states onto the foun- and the security dilemma inevita- dations of economics, game The field of international relations bly lead states into conflict, first theory, and methodological indi- has been quite transformed between with the concept of transnational vidualism and encourages the ap- the early 1960s, when Keohane en- relations, which undermines the plication of positivist techniques tered it, and the late 1990s, when his centrality -

International Institutions

Political Science International Institutions Yukari Iwanami 330 Harkness Hall [email protected] Office Hours: TBA Course Description This course will address questions such as why international organizations exist, whether they affect the behavior of states, how members’ domestic factors affect the decision-making process of an organization, and how power differences among states influence policy implementation of an international organization. The ultimate goal is to help students form their own opinions on the roles of formal organizations in international politics, the influence of major powers on interna- tional organizations, and their problems and limitations. We will read existing literature ranging from traditional approaches to empirical analyses, and focus on the problem of cooperation under anarchy, availability of outside options and lack of enforcement power, the issues of delegation, and the effects of voting rules and organizational membership on the decision-making process. Required Books • Robert Keohane, After Hegemony, Princeton University Press, 1984 • Lisa Martin and Beth Simmons eds. International Institutions. MIT Press, 2001 1 Introduction • J. Martin Rochester. 1986. “The Rise and Fall of International Organization as a Field of Study,” International Organization 40(4), 777-813 • Cheryl Shanks, Harold K. Jocobson, and Jeffrey H. Kaplan, Inertia and Change in the Con- stellation of International Governmental Organizations, 1981-1992, in Martin and Simmons 1 2 Problems under Anarchy This section addresses problems inherent in world politics. We discuss issues such as collective action problem, availability of outside options, power differences among states, and lack of en- forcement power. • Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action, chapter 1 and 2 • Garrett Hardin, 1968, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, 1243-48 • Eric Voeten, 2001, “Outside Options and the Logic of Security Council Action”, American Political Science Review, 95, 845-858 • James D. -

Gary King, Robert O. Keohane, Sidney Verba Designing Social Inquiry

Designing Social Inquiry Designing Social Inquiry SCIENTIFIC INFERENCE IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH Gary King Robert O. Keohane Sidney Verba PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY Copyright 1994 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In The United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data King, Gary. Designing social inquiry : scientific inference in qualitiative research / Gary King, Robert O. Keohane, Sidney Verba. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-691-03470-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-691-03471-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Social sciences—Methodology. 2. Social sciences— Research. 3. Inference I. Keohane, Robert Owen. II. Verba, Sidney. III. Title. H61.K5437 1994 93-39283 300′.72—dc20 CIP This book has been composed in Adobe Palatino Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources Printed in the United States of America 109876543 Third printing, with corrections and expanded index, 1995 Contents Preface ix 1 The Science in Social Science 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.1.1 Two Styles of Research, One Logic of Inference 3 1.1.2 Defining Scientific Research in Social Sciences 7 1.1.3 Science and Complexity 9 1.2 Major Components of Research Design 12 1.2.1 Improving Research Questions -

Understanding America's Contested Primacy

C E n t E r for Strat E g i C a n D B u D g E t a r y a S S E S S m E n t S Understanding America’s Contested Primacy Dr. Eric S. Edelman Understanding america’s contested Primacy Dr. Eric S. Edelman 2010 © 2010 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. About the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy and resource allocation. CSBA provides timely, impartial and insightful analyses to senior decision mak- ers in the executive and legislative branches, as well as to the media and the broader national security community. CSBA encourages thoughtful participation in the de- velopment of national security strategy and policy, and in the allocation of scarce human and capital resources. CSBA’s analysis and outreach focus on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to US national security. Meeting these challenges will require transforming the national security establishment, and we are devoted to helping achieve this end. About the Author Ambassador Eric S. Edelman retired as a Career Minister from the US Foreign Service on May 1, 2009. He has served in senior positions at the Departments of State and Defense as well as the White House where he led organizations providing analysis, strategy, policy development, secu- rity services, trade advocacy, public outreach, citizen services and con- gressional relations. -

From Community to Science (PDF, 4 Pages, 146.1

REVIEW From Community to Science by Clayton J. Cleveland Amitai Etzioni, From Empire to Community: A New Approach to International Relations. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004, 260 pp. $29.95 (paperback) ISBN 1403965358 This is an extremely timely work stressing two alternative paradigms of how the international system works as well as a possible route to negotiate the perils of both extremes. Rather than viewing the foundation of the system as one of several competing perspectives, Amitai Etzioni stresses the nature of the value systems that international actors adhere to in their attempts to navigate the problems emerging in a post–9/11 world. The two extremes Etzioni identifies as dominant perspectives fall along traditional lines of thought in international relations theory. The extreme right views power as the key attribute of the international system to determine outcomes while the extreme left views consensus and the idealistic promotion of human capabilities as the foundation of their respective values. Etzioni attempts to chart a course between these two extremes along a third way which he calls “soft communitarianism.” This perspective combines the values of the West with the foundations of non-Western ethics into a third possibility. Elements of both perspectives are incorporated into a synthesis of values that are capable of transcending the lines of division identified by many contemporary theorists.1 This book is organized around many of the themes that are relevant in today’s international order. These themes include the tensions between international and domestic forms of organization, state and non-state2 actors and the need to replace the current global architecture with a new form of organization capable of meeting the demands of the 21st century. -

International Political Economy

International Political Economy International Political Economy AN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY Benjamin J. Cohen PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2008 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Cohen, Benjamin J. ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12412-4 ISBN-13 (pbk.): 978-0-691-13569-4 This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 13579108642 For Jane Once more, with feeling CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Abbreviations xiii Introduction 1 CHAPTER ONE The American School 16 CHAPTER TWO The British School 44 CHAPTER THREE A Really Big Question 66 CHAPTER FOUR THe Control Gap 95 CHAPTER FIVE The Mystery of the State 118 CHAPTER SIX What Have We Learned? 142 CHAPTER SEVEN New Bridges? 169 References 179 Index 199 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1.1 Robert Keohane 26 Figure 1.2 Robert Gilpin 33 Figure 2.1 Susan Strange 46 Figure 3.1 Charles Kindelberger 69 Figure 3.2 Robert Cox 85 Figure 4.1 Steven Krasner 98 Figure 5.1 Peter Katzenstein 123 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AS USUAL, many debts of gratitude have been accumulated in the course of this project. I am especially grateful to the friends who took time from their busy schedules to read some or all of this manuscript while it was being drafted. These include Bob Cox, Marc Flandreau, Bob Gilpin, Joanne Gowa, Eric Hel- leiner, Miles Kahler, Peter Katzenstein, Bob Keohane, John Odell, Lou Pauly, Ronen Palan, and John Ravenhill.