Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye's Power and Interdependence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016 Professor: Office: Office Phone: Office Hours: Email: Course Description and Learning Outcomes Comparative politics is perhaps the broadest field of political science. This course will introduce students to the major theoretical approaches employed in comparative politics. The major debates and controversies in the field will be examined. Although some associate comparative politics with “the comparative method,” those conducting research in the area of comparative politics use a multitude of methodologies and pursue diverse topics. In this course, students will analyze and discuss the theoretical approaches and methods used in comparative politics. Course Requirements Class participation and attendance. Students must come to class prepared, having completed all of the required reading, and ready to actively discuss the material at hand. Each student must submit comments/questions on the assigned readings for six classes (not including the class you help facilitate). Please e-mail them to me by noon on the day of class. Students are expected to attend each class. Missing classes will have a deleterious effect on this portion of the grade. Arriving late, leaving early, or interrupting class with a phone or other electronic device will also result in a drop in the student’s grade. Students are not allowed to sleep, read newspapers or anything else, listen to headphones, TEXT, or talk to others during class. You must turn off all electronic devices during class. Any exceptions must be cleared with me in advance. Laptop computers and iPads are allowed for taking notes ONLY. I reserve the right to ban laptops, iPads, and so forth. -

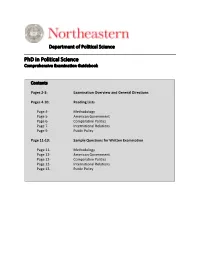

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Realism and Complex Interdependence

M02_KEOH2919_04_SE_C02.QXD 1/5/11 4:52 PM Page 19 CHAPTER2 Realism and Complex Interdependence One’s assumptions about world politics profoundly affect what one sees and how one constructs theories to explain events. We believe that the assumptions of politi- cal realists, whose theories dominated the postwar period, are often an inadequate basis for analyzing the politics of interdependence. The realist assumptions about world politics can be seen as defining an extreme set of conditions or ideal type. One could also imagine very different conditions. In this chapter, we shall construct another ideal type, the opposite of realism. We call it complex interdependence. After establishing the differences between realism and complex interdependence, we shall argue that complex interdependence sometimes comes closer to reality than does realism. When it does, traditional explanations of change in international regimes become questionable and the search for new explanatory models becomes more urgent. For political realists, international politics, like all other politics, is a struggle for power but, unlike domestic politics, a struggle dominated by organized violence. In the words of the most influential postwar textbook, “All history shows that nations active in international politics are continuously preparing for, actively involved in, or recovering from organized violence in the form of war.”1 Three assumptions are integral to the realist vision. First, states as coherent units are the dominant actors in world politics. This is a double assumption: states are predominant; and they act as coherent units. Second, realists assume that force is a usable and effective instru- ment of policy. Other instruments may also be employed, but using or threatening force is the most effective means of wielding power. -

Toward a More Democratic Congress?

TOWARD A MORE DEMOCRATIC CONGRESS? OUR IMPERFECT DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTION: THE CRITICS EXAMINED STEPHEN MACEDO* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 609 I. SENATE MALAPPORTIONMENT AND POLITICAL EQUALITY................. 611 II. IN DEFENSE OF THE SENATE................................................................ 618 III. CONSENT AS A DEMOCRATIC VIRTUE ................................................. 620 IV. REDISTRICTING AND THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE REFORM? ................ 620 V. THE PROBLEM OF GRIDLOCK, MINORITY VETOES, AND STATUS- QUO BIAS: UNCLOGGING THE CHANNELS OF POLITICAL CHANGE?.... 622 CONCLUSION................................................................................................... 627 INTRODUCTION There is much to admire in the work of those recent scholars of constitutional reform – including Sanford Levinson, Larry Sabato, and prior to them, Robert Dahl – who propose to reinvigorate our democracy by “correcting” and “revitalizing” our Constitution. They are right to warn that “Constitution worship” should not supplant critical thinking and sober assessment. There is no doubt that our 220-year-old founding charter – itself the product of compromise and consensus, and not only scholarly musing – could be improved upon. Dahl points out that in 1787, “[h]istory had produced no truly relevant models of representative government on the scale the United States had already attained, not to mention the scale it would reach in years to come.”1 Political science has since progressed; as Dahl also observes, none of us “would hire an electrician equipped only with Franklin’s knowledge to do our wiring.”2 But our political plumbing is just as archaic. I, too, have participated in efforts to assess the state of our democracy, and co-authored a work that offers recommendations, some of which overlap with * Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Politics and the University Center for Human Values; Director of the University Center for Human Values, Princeton University. -

Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar

The Profession ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar Michael Peress, SUNY–Stony Brook ABSTRACT This article develops a number of measures of the research productivity of politi- cal science departments using data collected from Google Scholar. Departments are ranked in terms of citations to articles published by faculty, citations to articles recently published by faculty, impact factors of journals in which faculty published, and number of top pub- lications in which faculty published. Results are presented in aggregate terms and on a per-faculty basis. he most widely used measure of the quality of of search results, from which I identified publications authored political science departments is the US News and by that faculty member, the journal in which the publication World Report ranking. It is based on a survey sent appeared (if applicable), and the number of citations to that to political science department heads and direc- article or book. tors of graduate studies. Respondents are asked to I constructed four measures for each faculty member. First, Trate other political science departments on a 1-to-5 scale; their I calculated the total number of citations. This can be -

Achieving Cooperating Under Anarchy,” by Robert Axelrod and Robert Keohane, 1985

Devarati Ghosh “Achieving Cooperating Under Anarchy,” by Robert Axelrod and Robert Keohane, 1985 · Definitions: remember that for cooperation to occur, there must be some combination of conflicting and shared interests. Cooperation is distinct from harmony, where there is a total identity of interests between states. Anarchy is the absence of common world government, but it does not imply that the world is devoid of organizational forms. · Three dimensions of structure impact the incentives for states to cooperate: the mutuality of interests, the shadow of the future, and the number of players. The mutuality of interests—is determined by an objective structure of material payoffs, as well as upon actors’ perceptions of that structure. Changes in beliefs about other players, as well as about the most optimal policy, may cause state leaders to prefer unilateral action. This is true of both political-economic and security issues. · The longer the shadow of the future, the more the costs of defection offset the short-term incentive to defect. This is more true of political-economic issues, where there is a greater likelihood of extended interaction, than of security issues, where a successful preemptive war would seriously advantage one of the players. Also important is the ability of states to identifying defection, which Axelrod and Keohane believe does not distinguish political-economic issues from security ones. · Once defection has been identified, the next problem is sanctioning the cheater. This becomes significantly more difficult when there is a large number of actors. Defection can be costly, so there must be enough incentive for states to punish defectors. -

NEOREALIST and NEO-GRAMSCIAN HEGEMONY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS and CONFLICT RESOLUTION DURING the 1990’S

Ekonomik ve Sosyal Ara ştırmalar Dergisi, Güz 2005, 1:88-114 NEOREALIST AND NEO-GRAMSCIAN HEGEMONY IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION DURING THE 1990’s Sezai ÖZÇEL İK George Mason University, Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, 3330 N. Washington Blvd. Truland Building, 5th Floor Arlington, VA 22201 [email protected] 1990’LU YILLARDA ULUSLARARASI İLİŞ KİLER VE ÇATI ŞMA ÇÖZÜMÜNDE NEOREAL İZM VE NEO- GRAMS İYAN HEGEMONYA KAVRAMI Abstract The article aims to explain international relations and conflict resolution in combination with the neorealist and neo-Gramscian notions of the hegemony during the 1990s. In the first part, it focuses on neorealist hegemony theories. The Hegemonic Stability Theory (HST) is tested for viability as an explanatory tool of the Cold-War world politics and conflict resolution. Because of the limitations of neorealist hegemony theories, the neo-Gramscian hegemony and related concepts such as historic bloc, passive revolution, civil society and war of position/war of movement are elaborated. Later, the Coxian approach to international relations and world order is explained as a critical theory. Finally, the article attempts to establish a model of structural conflict analysis and resolution. Keywords: Neo-realism, Neo-Gramscian, Hegemony, Conflict Resolution, International Relations Özet Bu makale uluslararası ili şkiler ve çatı şma çözümü kuramlarını neorealist ve neo- Gramsiyan hegemonya kavramlarını çerçevesinde 1990’lı yılları kapsayacak şekilde açıklamayı hedeflemektedir. Birinci -

Power, Interdependence, and Nonstate Actors in World Politics Is Published by Princeton University Press and Copyrighted, © 2009, by Princeton University Press

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Edited by Helen V. Milner & Andrew Moravcsik: Power, Interdependence, and Nonstate Actors in World Politics is published by Princeton University Press and copyrighted, © 2009, by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. Follow links Class Use and other Permissions. For more information, send email to: [email protected] CHAPTER 1 Power, Interdependence, and Nonstate Actors in World Politics RESEARCH FRONTIERS Helen V. Milner IN THE MID-1970S a new paradigm emerged in international relations. While many of the ideas in this new paradigm had been discussed previ ously, Keohane and Nye put these pieces together in a new and fruitful way to erect a competitor to realism and its later formulation, neoreal ism.1 First elaborated in Power and Interdependence, this paradigm is now usually referred to as neoliberal institutionalism. In the thirty years since Power and Interdependence, this new paradigm has developed substan tially and has become the main alternative to realism for understanding international relations. Keohane’s seminal work, After Hegemony, which is a centerstone of the neoliberal paradigm, provided the most compelling theoretical justification for the existence and role of international institu tions in world politics.2 Since then the progress of the neoliberal para digm can be plainly seen in a number of key works, such as Legalization and World Politics, The Rational Design of International Institutions, and Delegation and Agency in International Organizations.3 Each of these projects, and many others, takes the key ideas of the neoliberal in stitutionalist paradigm and pushes them forward into new areas of re search. -

The Theory of Hegemonic Stability

US-Western European Economic Relations, 1940-1973 Date Event Significance 1941-44 US-UK wartime Technocratic elites in both countries negotiate in negotiations on a new circumstances relatively free of normal domestic international monetary political pressure and trading system July 1944 Bretton Woods Creation of the Bretton Woods twins, the IMF and conference World Bank December 1945 US loan to Britain US attempt to force Britain to accept the Bretton agreed Woods rules June 1947 US Secretary of State A large step away from Bretton Woods towards direct Marshall announces US aid and promoting regionalism in Europe ‘Marshall aid’ July-August British pound returns to The final failure of Hull’s vision of forcing Britain to 1947 convertibility, but this is accept Bretton Woods revoked as reserves are rapidly drained 30 October GATT signed in Geneva Interim agreement on trade principles, and draft 1947 agreement on the establishment of the ITO by 23 countries March 1948 Havana World Agreement on the charter of the ITO by over 60 Conference on Trade and countries Employment June 1950 Creation of European Facilitated the reconstruction of European trade and Payments Union payments on a regional basis, rather than on the basis of Bretton Woods April 1951 Signing of the Treaty of Creates the European Coal and Steel Community Paris March 1957 Signing of the Treaty of Creates the EEC and Euratom, the former leading to the Rome creation of a large trading bloc, changing the nature of GATT bargaining December 1958 European currencies The Bretton -

Economic Interdependence and Strategic Interest: China, India, and the United States in the New Global Order

Economic Interdependence and Strategic Interest: China, India, and the United States in the New Global Order John Echeverri-Gent, April Herlevi, and Kim Ganczak Department of Politics P.O. Box 400787 University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 22904-4787 Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Phone: (434)924-3968 Fax: (434)924-3359 Economic Interdependence and Strategic Interest: China, India, and the United States in the New Global Order1 “If the last century was the age of alliances, this is an era of inter-dependence.” Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Address at Tsinghua University, Beijing May 15, 2015 International political economy and strategic studies are usually analyzed by distinct scholarly communities. Thus, the consequences of the changing global economy for the pursuit of strategic interests has not been adequately analyzed. This paper calls for a new approach to analyzing the relationship between global markets and the pursuit of strategic interests by rigorously documenting changes in the global economy and employing insights from social network theory. We then elaborate on the implications of these changes for relations between China, India, and the United States. Social network theory is a promising methodology for describing these issues because it introduces concepts such as centrality and density that better measure changes in the global economy. Concepts of indirect dependence and interaction among networked actors offer novel insights that illuminate the complexity and contingency of strategic interests in the contemporary global setting. The development of global markets has made the world more economically interdependent. Our paper shows how this change is not only a matter of increased interdependence but involves qualitative change. -

Chapter-02.Pdf

Name: Class: Date: Chapter 02 1. Which of the following is derived from a set of assumptions and evidence about some phenomenon? a. a framework b. a theory c. a paradigm d. a normative proposition 2. Which of the following refers to a dominant way of looking at a particular subject, which structures our thought about an area of inquiry? a. a paradigm b. a theory c. a normative proposition d. a hypothesis 3. Which political movement in the United States calls for the use of military and economic power in foreign policy to bring freedom and democracy to other countries? a. liberalism b. realism c. defensive realism d. neoconservatism 4. Which three important applications do theories have for policy makers? a. diagnosis, prescription, and lesson-drawing b. persuasion, prescription, and prognosis c. prescription, description, and retrospection d. inference, prescription, and prognosis 5. Which of the following is the oldest of the prevailing schools of thought in international relations? a. realism b. neoconservatism c. feminism d. liberalism 6. Whose writings can the realist theory of international relations be traced to? a. St. Augustine’s b. Hugo Grotius’s c. Thucydides’s d. Carl Marx’s 7. Realists argue that the condition of anarchy typically leads to which of the following? a. chaos b. interdependence c. war Copyright Cengage Learning. Powered by Cognero. Page 1 Name: Class: Date: Chapter 02 d. self-help 8. Which of the following statements best describes the notion of relative gains? a. “Winning is more important than doing well.” b. “Doing well is more important than winning.” c. -

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010 Gary King, Robert Putnam, and Sidney Verba Thursdays 12-2pm, Littauer M-17 Gary King [email protected], http://GKing.Harvard.edu Phone: 617-495-2027 Office: 34 Kirkland Street Robert Putnam [email protected] Phone: 617-495-0539 Office: 79 JFK Street, T376 Sidney Verba [email protected] Phone: 617-495-4421 Office: Littauer Center, M18 Prerequisite or corequisite: Gov1000 Overview If you could learn only one thing in graduate school, it should be how to do scholarly research. You should be able to assess the state of a scholarly literature, identify interesting questions, formulate strategies for answering them, have the methodological tools with which to conduct the research, and understand how to write up the results so they can be published. Although most graduate level courses address these issues indirectly, we provide an explicit analysis of each. We do this in the context of a variety of strategies of empirical political inquiry. Our examples cover American politics, international relations, compara- tive politics, and other subfields of political science that rely on empirical evidence. We do not address certain research in political theory for which empirical evidence is not central, but our methodological emphases will be as varied as our substantive examples. We take empirical evidence to be historical, quantitative, or anthropological. Specific methodolo- gies include survey research, experiments, non-experiments, intensive interviews, statistical analyses, case studies, and participant observation. Assignments Weekly reading assignments are listed below. Since our classes are largely participatory, be sure to complete the readings prior to the class for which they are as- signed.