Realism and Complex Interdependence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power, Interdependence, and Nonstate Actors in World Politics Is Published by Princeton University Press and Copyrighted, © 2009, by Princeton University Press

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Edited by Helen V. Milner & Andrew Moravcsik: Power, Interdependence, and Nonstate Actors in World Politics is published by Princeton University Press and copyrighted, © 2009, by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. Follow links Class Use and other Permissions. For more information, send email to: [email protected] CHAPTER 1 Power, Interdependence, and Nonstate Actors in World Politics RESEARCH FRONTIERS Helen V. Milner IN THE MID-1970S a new paradigm emerged in international relations. While many of the ideas in this new paradigm had been discussed previ ously, Keohane and Nye put these pieces together in a new and fruitful way to erect a competitor to realism and its later formulation, neoreal ism.1 First elaborated in Power and Interdependence, this paradigm is now usually referred to as neoliberal institutionalism. In the thirty years since Power and Interdependence, this new paradigm has developed substan tially and has become the main alternative to realism for understanding international relations. Keohane’s seminal work, After Hegemony, which is a centerstone of the neoliberal paradigm, provided the most compelling theoretical justification for the existence and role of international institu tions in world politics.2 Since then the progress of the neoliberal para digm can be plainly seen in a number of key works, such as Legalization and World Politics, The Rational Design of International Institutions, and Delegation and Agency in International Organizations.3 Each of these projects, and many others, takes the key ideas of the neoliberal in stitutionalist paradigm and pushes them forward into new areas of re search. -

Economic Interdependence and Strategic Interest: China, India, and the United States in the New Global Order

Economic Interdependence and Strategic Interest: China, India, and the United States in the New Global Order John Echeverri-Gent, April Herlevi, and Kim Ganczak Department of Politics P.O. Box 400787 University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 22904-4787 Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Phone: (434)924-3968 Fax: (434)924-3359 Economic Interdependence and Strategic Interest: China, India, and the United States in the New Global Order1 “If the last century was the age of alliances, this is an era of inter-dependence.” Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Address at Tsinghua University, Beijing May 15, 2015 International political economy and strategic studies are usually analyzed by distinct scholarly communities. Thus, the consequences of the changing global economy for the pursuit of strategic interests has not been adequately analyzed. This paper calls for a new approach to analyzing the relationship between global markets and the pursuit of strategic interests by rigorously documenting changes in the global economy and employing insights from social network theory. We then elaborate on the implications of these changes for relations between China, India, and the United States. Social network theory is a promising methodology for describing these issues because it introduces concepts such as centrality and density that better measure changes in the global economy. Concepts of indirect dependence and interaction among networked actors offer novel insights that illuminate the complexity and contingency of strategic interests in the contemporary global setting. The development of global markets has made the world more economically interdependent. Our paper shows how this change is not only a matter of increased interdependence but involves qualitative change. -

Chapter-02.Pdf

Name: Class: Date: Chapter 02 1. Which of the following is derived from a set of assumptions and evidence about some phenomenon? a. a framework b. a theory c. a paradigm d. a normative proposition 2. Which of the following refers to a dominant way of looking at a particular subject, which structures our thought about an area of inquiry? a. a paradigm b. a theory c. a normative proposition d. a hypothesis 3. Which political movement in the United States calls for the use of military and economic power in foreign policy to bring freedom and democracy to other countries? a. liberalism b. realism c. defensive realism d. neoconservatism 4. Which three important applications do theories have for policy makers? a. diagnosis, prescription, and lesson-drawing b. persuasion, prescription, and prognosis c. prescription, description, and retrospection d. inference, prescription, and prognosis 5. Which of the following is the oldest of the prevailing schools of thought in international relations? a. realism b. neoconservatism c. feminism d. liberalism 6. Whose writings can the realist theory of international relations be traced to? a. St. Augustine’s b. Hugo Grotius’s c. Thucydides’s d. Carl Marx’s 7. Realists argue that the condition of anarchy typically leads to which of the following? a. chaos b. interdependence c. war Copyright Cengage Learning. Powered by Cognero. Page 1 Name: Class: Date: Chapter 02 d. self-help 8. Which of the following statements best describes the notion of relative gains? a. “Winning is more important than doing well.” b. “Doing well is more important than winning.” c. -

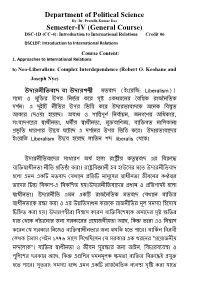

Department of Political Science Semester-IV (General Course)

Department of Political Science By: Dr. Prafulla Kumar Das Semester-IV (General Course) DSC-1D (CC-4): Introduction to International Relations Credit 06 DSC1DT: Introduction to International Relations Course Content: 1. Approaches to International Relations b) Neo-Liberalism: Complex Interdependence (Robert O. Keohane and Joseph Nye) ( : Liberalism)) ও উপ উপ উ ও ও প , , প , , , উ উপ উ Liberalism উ liberalis উ । উ উ - ।উ ও প । উ ও উ । উ প , ও ও প । প ১৭৭৬ " "। ও , ও প , প । প , ও । উ ও উৎ ও প ও প উ উ প , প প ও প প ও উ ও , , ও ও ও , উ , ও , , ও । উ প , ও উ - ৎ , উ প , ও ও । Complex interdependence Complex interdependence in international relations is the idea put forth by Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye. The term "complex interdependence" was claimed by Raymond Leslie Buell in 1925 to describe the new ordering among economies, cultures and races. The very concept was popularized through the work of Richard N. Cooper (1968). With the analytical construct of complex interdependence in their critique of political realism, "Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye go a step further and analyze how international politics is transformed by interdependence" . The theorists recognized that the various and complex transnational connections and interdependencies between states and societies were increasing, while the use of military force and power balancing are decreasing but remain important. In making use of the concept of interdependence, Keohane and Nye also importantly differentiated between interdependence and dependence in analyzing the role of power in politics and the relations between international actors. -

Re-Examination of the Economic Interdependence Between China and Japan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE ICCS Journal of Modern Chinese Studies Vol.11 (1) 2018 論文 Re-examination of the Economic Interdependence between China and Japan LU Longjiang1 Abstract China and Japan, the world’s second and third largest economies. They have established one of the biggest bilateral trade relationships in the world and also is considered as close economic interdependence. However, tensions between these two countries have further escalated in recent years. Why economic interdependence cannot prevent the escalating tensions between China and Japan? This article tries to re-visit the theory of economic interdependence, in order to tackle the puzzle between economic interdependence and conflict in the case of Sino-Japanese relationship. I will demonstrate the key features on the development process of this economic interdependence relationship and show the dynamic change of increasingly obvious flaws in this relationship. In this context, I emphasize the necessity of establishing coordination mechanism between China and Japan, which can ease the anxiety of the two governments for the unfavorable situation brought by the worsening flaws in this economic interdependence. The Sino-Japanese relationship was seriously affected by these two factors: the increasingly obvious flaws on the one hand and the effort of both governments to build the coordination mechanism on the other hand, during the first decade of 21st century. These two factors working together have led to the repeated unstable situation between China and Japan in the 2000s. More importantly, the frustration with the establishment of the coordination mechanism in the case of Sino-Japanese relationship is the most important factor leads to the escalating current tensions. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Complex

The London School of Economics and Political Science Complex Interdependence and China’s Engagement with Australia --- Navigating between Power and Vulnerability Yixiao Zheng A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2014 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,616 words. 2 Abstract China has become heavily dependent on Australia for resource supply as a result of her rapid economic growth over the 2000s. Stable and reliable resource supply from Australia has become a matter of national economic security. Yet, China’s resource relationship with Australia is grown out of a delicate geopolitical framework, because Australia is not only a resource superpower but also a staunch U.S. ally in the Asia-Pacific region. Despite extensive economic interdependence between the two countries, China faces a huge challenge to build a genuinely reliable and close resource partnership with Australia. -

Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye's Power and Interdependence

15 A circumspect revival of liberalism: Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye’s Power and Interdependence Thomas C. Walker1 Classic works in International Relations (IR) can emerge in a variety of ways. Some classics introduce a new paradigm that explains complex phenomena better than pre- vious efforts. Others revive neglected but important ideas and claims. Still others hit the tenor of the times and speak to immediate challenges facing global politics. Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye’s Power and Interdependence (PI), first published in 1977, is indeed a classic for all of these reasons.2 Unlike some of the works discussed in this volume, Keohane and Nye’s work was promptly hailed as a classic. Two of the leading IR journals published article-length reviews of PI shortly after its publication. In International Organization, Kal Holsti surmised that this book may ‘prove to be one of the most significant writings in international relations theory of the past two decades’.3 In an extensive review published in World Politics, Stanley Michalak referred to PI as ‘a groundbreaking work … that will have a long-term impact on the ways in which teachers and scholars conceptualize international phenomena’.4 Both of these reviewers were prescient. The themes and puzzles presented in PI continue to shape our thinking on globalization, international trade, regime formation and change, non-state actors as well as the nature of power and military force in the global realm. PI was an early collaboration between two young scholars who would both become ranked among the most influential in the field of IR. -

Chapter 3: Theories of International Relations: Realism and Liberalism

Chapter 3: Theories of International Relations: Realism and Liberalism MULTIPLE CHOICE 1. According to the author, the state of theory in international politics is characterized by a. Misunderstanding and fear c. disagreement and debate b. widespread agreement and cooperation d. misperception and suspicion 2. The two oldest theories of international politics are a. Socialism and Marxism c. Autocracy and Democracy b. Structuralism and Constructivism d. Realism and Liberalism 3. Realism focuses on which of the following? a. trade c. democratization b. power d. international law 4. All but one of the following is an assumption of Realism. a. Anarchy c. International cooperation b. States as main actors d. States as rational actors 5. The assumption that claims states are rational actors means that they a. always make the correct decision. b. always make the best decision. c. have consistent, ordered preferences and calculate the costs and benefits of all policies. d. always make decisions in the national interest. 6. “If states are to survive, they must rely on their own means.” Which term best fits this statement? a. anarchy c. unitary actors b. balance of power d. self-help 7. The security dilemma refers to a. the tendency for one state’s efforts to obtain security to cause insecurity in others. b. the hesitation to go to war against another country. c. efforts of states to stake their survival on agreements with other states. d. the willingness of states to always cooperate with each other. 8. The 2 x 2 box in which strategies of defection and cooperation are critically linked to each other is called a. -

Weaponized Interdependence Weaponized Henry Farrell and Interdependence Abraham L

Weaponized Interdependence Weaponized Henry Farrell and Interdependence Abraham L. Newman How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion In May 2018, Donald Trump announced that the United States was pulling out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreement on Iran’s nuclear program and re- imposing sanctions. Most notably, many of these penalties apply not to U.S. ªrms, but to foreign ªrms that may have no presence in the United States. The sanctions are consequential in large part because of U.S. importance to the global ªnancial network.1 This unilateral action led to protest among the United States’ European allies: France’s ªnance minister, Bruno Le Maire, tartly noted that the United States was not the “economic policeman of the planet.”2 The reimposition of sanctions on Iran is just one recent example of how the United States is using global economic networks to achieve its strategic aims.3 While security scholars have long recognized the crucial importance of energy markets in shaping geostrategic outcomes,4 ªnancial and information markets Henry Farrell is Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at George Washington University. Abraham L. Newman is Professor at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service and the Government Department at Georgetown University. The authors are grateful to Miles Evers, Llewellyn Hughes, Woojeong Jang, Erik Jones, Miles Kahler, Nikhil Kalyanpur, Matthias Matthijs, Kathleen McNamara, Daniel Nexon, Gideon Rose, Mark Schwartz, and William Winecoff, as well as the anonymous reviewers for comments and criticism. Charles Glaser provided especially detailed and helpful comments on an early draft. Previous versions of this article were presented at the 2018 annual convention of the Interna- tional Studies Association and at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies Research Seminar in Politics and Political Economy on April 17, 2018. -

ECONOMIC INTERDEPENDENCE and STRATEGIC THINKING in SINO-JAPANESE RELATIONS: Reconsidering the Amendment of Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan

ASIA PROGRAM ECONOMIC INTERDEPENDENCE AND STRATEGIC THINKING IN SINO-JAPANESE RELATIONS: Reconsidering the amendment of article 9 of the Constitution of Japan BY PAUL ANDRÉ ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR AT THE SCHOOL OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND ECONOMICS OF WASEDA UNIVERSITY (JAPAN) FEBRUARY 2018 ASIA FOCUS #63 ASIA FOCUS #63–ASIA PROGRAM / February 2018 This paper aims at understanding the importance of economic interdependence with China in Japan’s relation to war; and its willingness to amend its pacifist Constitution and thus to legalize the use of war. I first come back to Raymond Aron’s idea that war cannot be excluded from the industrial society. But the latter changes the relation to the conflict. Then I use Dale Copeland’s model and I try to demonstrate that the Japanese government is anticipating a Chinese threat which tends to present economic interdependence as a threat and to reinforce Japan’s willingness to ensure national security by armed forces. ar in international relations was often badly thought of. Some might see war _ interstate violence _ as an archaic _ almost childish _ modality to W approach international conflicts. For a long time, the study of war in the international economy was underdeveloped, and there have been too little books on this topic. Globalization, the acceleration of economic interdependence, or the proliferation of regional partnerships seem to give more strength to liberalists who consider the development of international trade is not only a factor in pacifying international relations (commercial liberalism thesis)1 but also it is a factor of democratization. In the liberal theory, democracies do not wage war against each other. -

Theory of Complex Interdependence: a Comparative Analysis of Realist and Neoliberal Thoughts

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 2; February 2015 Theory of Complex Interdependence: A Comparative Analysis of Realist and Neoliberal Thoughts Waheeda Rana PhD Scholar at Quaid- i-Azam University Islamabad & Assistant Professor at International Islamic University Islamabad Abstract The post-Cold War era witnessed a realization among the nation-states that the criteria for achieving real power was something beyond hard power, rather it required a secure economic and technological advancement. This led to an interesting debate between realists and liberals, each trying to convince that their arguments were more valid and relevant to prevailing global trends. In the context of this debate, this paper seeks to critically analyze the theory of ‘Complex Interdependence’ which challenged the fundamental assumptions of traditional and structural realism. Complex Interdependence became a central component of the neoliberal perspective. It highlighted the emergence of transnational actors vis-à-vis the state. Complex Interdependence model tried to synthesize the realist and liberal perspectives. Thus the main aim of this paper is to carry out a comparative analysis of realist and neoliberal schools of thought and to explore the prevalence of these approaches in the contemporary world politics. The major conclusion of this paper is that following the rise of international regimes and institutions, the traditional military capabilities have been compensated with the importance of welfare and trade in foreign policy matters. It concludes that the neoliberal perspective has attained much importance and there is an obvious willingness among the states to enter into cooperative alliances with one another under conditions of anarchy and dependence even. -

Paper: Theories of International Relations and World History Lesson

Liberalism and Neo-Liberalism Paper: Theories of International Relations and World History Lesson : Liberalism and Neo-Liberalism Lesson Developer: anuranjita Wadhwa College/Department: Bharti College, University of Delhi Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Liberalism and Neo-Liberalism Contents Introduction 1 Core ideas of Liberalism 1.1 Classical Liberal Thinkers 2 Early Liberal ideas in international relations 2.1 Utopian Liberalism 3. Dominant Strands of Liberal Thinking 3.1 Liberal Institutions 3.1.1 Institutions in a multipolar world 3.2 Interdependence Liberalism 3.2.1 Commercial Liberalism in the nineteenth century 3.2.2 Interdependence to integration 3.2.3 Complex Interdependence 3.2.4 Restraints on interdependence 3.3 Republican Liberalism 3.3.3 Inconsistencies in Republican liberalism 3.3.1 The foundation stone of peace 3.3.2 Establishment of ‘Zones of Peace’ 3.3.3 Inconsistencies in Republican liberalism 4. The continuing debate between realism and liberalism 5 The neo versus neo debate 5.1 Liberalism moderated by neo realist assumptions 5.2 Liberal ideals under globalization 5.2.1 Stability due to hegemony 5.2.2 Imposition of the liberal order 6 Change in the approach of bringing peace 7 Conclusion 8 Summary 9 Glossary 10 MCQs 11 Short Questions with answers 12 Long Questions Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Liberalism and Neo-Liberalism Introduction Realism with its chief concern on power politics amongst the states defends dominance strategy to promote national interest. In contrast liberalism with its optimistic approach towards the solution of a problem through the collective efforts of the states believes in the attainment of perpetual peace amongst the states through cooperation.