Border Management and Migration Controls in Poland Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Right of Persons Employed in Polish Public Services to Association in Trade Unions

Studia z Zakresu Prawa Pracy i Polityki Społecznej Studies on Labour Law and Social Policy 2020, 27, nr 1: 23–27 doi:10.4467/25444654SPP.20.003.11719 www.ejournals.eu/sppips Krzysztof Baran https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5165-8265 Jagiellonian University THE RIGHT OF PERSONS EMPLOYED IN POLISH PUBLIC SERVICES TO ASSOCIATION IN TRADE UNIONS Abstract The article aims at presenting the reconsidered model of association of public servants under the Polish legal system. In the past, there was a statutory imposed limiting monism in the trade union movement of military services officers. Since 2019 trade union pluralism has been introduced for the Police, Border Guard, and Prison Service officers, which is analyzed in the paper. Another issue discussed in this article is the right of association of persons employed in civil public administration. Słowa kluczowe: związek zawodowy, służby mundurowe, straż graniczna, policja, służba więzienna Keywords: trade union, public services, Border Guard, Police, Prison Service ASJC: 3308, JEL: K31 On 19 July 2019, the Parliament of the Republic of Poland adopted the Act extending the right of officers of the Police, Border Guard and Prison Services to form and join trade unions (Dz.U. 2019, item 1608). The newly adopted regulation is an inspiration to recon- sider the model of association of public servants under the Polish legal system. The term “public servants” or “those employed in public services” refers not only to those employed in widely understood public administration, but also those serving in military services. The starting point for further discussion will be the statement that persons who are employed in Polish public service structures perform work under various legal regimes, starting from labour law, through civil law to administrative law. -

Trafficking in Human Beings

TemaNord 2014:526 TemaNord Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K www.norden.org Trafficking in Human Beings Report from a conference on Identification of victims and criminals Trafficking in Human Beings – why we do not notice them In the Nordic countries, most of the reported cases of trafficking in human beings today concern women and girls trafficked for sexual exploitation, but experiences from Europe indicate that human trafficking has increased also in farming, household work, construction, and house building, as well as in begging, shoplifting and thefts. The conference Identification of victims and criminals – why we do not notice them on 30–31 May 2013 in Tallinn, Estonia formed the conclusion of a Nordic-Baltic-Northwest Russian cooperation project. Around 80 participants attended the two-day conference to discuss ways of identifying victims and criminals and to find answer to the question of why we do not notice victims or criminals, even though we now have available to us facts, figures, research and knowledge about human trafficking as a part of international organized crime. TemaNord 2014:526 ISBN 978-92-893-2767-1 ISBN 978-92-893-2768-8 (EPUB) ISSN 0908-6692 conference proceeding TN2014526 omslag.indd 1 09-04-2014 07:18:39 Trafficking in Human Beings Report from a conference on Identification of victims and criminals – why we do not notice them TemaNord 2014:526 Trafficking in Human Beings Report from a conference on Identification of victims and criminals - why we do not notice them ISBN 978-92-893-2767-1 ISBN 978-92-893-2768-8 (EPUB) http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2014-526 TemaNord 2014:526 ISSN 0908-6692 © Nordic Council of Ministers 2014 Layout: Hanne Lebech Cover photo: Beate Nøsterud Photo: Reelika Riimand Print: Rosendahls-Schultz Grafisk Copies: 516 Printed in Denmark This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers. -

Summer 09.Qxd

David Lewis, senior research fellow in the Department of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford, England, served previously as director of the International Crisis Group’s Central Asia Project, based in Kyrgyzstan. High Times on the Silk Road The Central Asian Paradox David Lewis In medieval times, traders carried jewels, seems like a major threat to the region, spices, perfumes , and fabulous fabrics along since it is so inextricably linked to violent the legendary Silk Route through Central crime and political instability in many other Asia. Today, the goods are just as valuable, parts of the world . More people died in but infinitely more dangerous. Weapons and Mexican drug violence in 2009 than in Iraq. equipment for American troops in Afghan- In Brazil , the government admits about istan travel from west to east, along the 23,000 drug-related homicides each year— vital lifeline of the Northern Supply Route. some ten times the number of civilians In the other direction, an unadvertised, but killed in the war in Afghanistan . And it ’s no less deadly product travels along the not just Latin America that suffers. On same roads, generating billions of dollars in Afghanistan’s border with Iran, there are illicit profits. As much as 25 percent of regular clashes between Iranian counter- Afghanistan’s heroin production is exported narcotics units and drug smugglers. Hun - through the former Soviet states of Central dreds of border guards have been killed Asia, and the UN’s drug experts express over the past decade in fights with heroin grave concerns . Antonio Maria Costa, head and opium traffickers. -

14819/06 DCL 1 /Dl GSC.SMART.2.C Delegations Will Find Attached The

Council of the European Union Brussels, 1 August 2018 (OR. en) 14819/06 DCL 1 SCH-EVAL 177 FRONT 221 COMIX 916 DECLASSIFICATION of document: ST14819/06 RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED dated: 10 November 2006 new status: Public Subject: Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND : report on Land Borders Delegations will find attached the declassified version of the above document. The text of this document is identical to the previous version. 14819/06 DCL 1 /dl GSC.SMART.2.C EN RESTREINT COUNCIL OF Brussels, 10 November 2006 THE EUROPEAN UNION 14819/06 RESTREINT UE SCH-EVAL 177 FRONT 221 COMIX 916 REPORT from: the Land BordersEvaluation Committee to: the Schengen Evaluation Working Party Subject : Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND : report on Land Borders TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Management summary ............................................................................................................... 4 3. General information .................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. Strategy ............................................................................................................................. 5 3.2. Organisational (functional) structure ................................................................................ 9 3.3. Operational effectiveness ............................................................................................... -

Some Facts About Southeast Finland Frontier Guard

THE SOUTHEAST FINLAND BORDER GUARD DISTRICT THETHE SOUTHEA SOUTHEASTST FINLAND FINLAND BORDER BORDER GUA GUARDRD DISTRICT DISTRICT Border guard stations 10 Border check station 1 II/123 Border crossing points 8 Uukuniemi International Pitkäpohja Kolmikanta Restricted Imatra BGA (Parikkala) Kangaskoski Immola Personnel 1.1.2006: • headquarters Lake Ladoga • logistics base Niskapietilä Officers 95 Lappeenranta BGA Pelkola Border guards 570 (Imatra) Others 87 Lappeenranta airport Total 752 Nuijamaa Common border with Vehicles: Vainikkala Russia 227 km Virolahti Cars 65 BGA Leino Motorbikes 15 Vyborg Snowmobiles 59 Patrol boats 11 Vaalimaa Vaalimaa Hurppu Dogs 95 (Santio) VI/11 Gulf of Finland BORDERBORDER SECURITYSECURITY SYSTEMSYSTEM ININ SOUTHEASOUTHEASTST FINLAFINLANDND (figures/2005) BORDERBORDER CO-OPERATION WITH SURVEILLASURVEILLANCENCE NATIONAL AUTHORITIES • exposed illegal border crossings 16 • accomplished refused entries 635 • executive assistances 23 • assistances, searches 25 4 3 2 1 CO-OPERATION OVER THE BORDER RUSSIAN BORDER GUARD SERVICE • apprehended ~80 • meetings: • border delegates/deputies 22 • assistants of the border delegates 70 BORDERBORDER CHECKSCHECKS CONSULATES • refusals of entry 707 • ST. PETERSBURG • discovered fraudulent documents 128 • MOSCOW • discovered stolen vehicles 13 • PETROZAVODSK • discovered fraudulent documents 88 BORDERBORDER CHECKSCHECKS Investment: v. 2004 392 man-years; 19,0 mill. € v. 2005 409 man-years; 19,5 mill. € PASSENGERPASSENGER TRAFFIC TRAFFIC 1996 1996 - -20052005 4 764 495 4 694 657 -

024682/EU XXVI. GP Eingelangt Am 05/06/18

024682/EU XXVI. GP Eingelangt am 05/06/18 Council of the European Union Brussels, 5 June 2018 (OR. en) 8832/1/06 REV 1 DCL 1 SCH-EVAL 78 FRONT 89 COMIX 408 DECLASSIFICATION of document: ST8832/1/06 REV 1 RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED dated: 20 July 2006 new status: Public Subject: Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND: report on Sea Borders Delegations will find attached the declassified version of the above document. The text of this document is identical to the previous version. 8832/1/06 REV 1 DCL 1 /dl DGF 2C EN www.parlament.gv.at RESTREINT UE COUNCIL OF Brussels, 20 July 2006 THE EUROPEAN UNION 8832/1/06 REV 1 RESTREINT UE SCH-EVAL 78 FRONT 89 COMIX 408 REPORT from: the Evaluation Committee Sea Borders to: the Schengen Evaluation Working Party Subject : Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND: report on Sea Borders This report was made by the Evaluation Committee Sea Borders and will be brought to the attention of the Sch-Eval Working Party which will ensure a report and the presentation of the follow-up thereto to the Council. 8832/1/06 REV 1 EB/mdc 1 DG H 2 RESTREINT UE EN www.parlament.gv.at RESTREINT UE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Management summary ............................................................................................................... 5 3. General information ................................................................................................................... -

Border Management Reform in Transition Democracies

Border Management Reform in Transition Democracies Editors Aditya Batara G Beni Sukadis Contributors Pierre Aepli Colonel Rudito A.A. Banyu Perwita, PhD Zoltán Nagy Lieutenant-Colonel János Hegedűs First Edition, June 2007 Layout Front Cover Lebanese-Israeli Borders Downloaded from: www.michaelcotten.com Printed by Copyright DCAF & LESPERSSI, 2007 The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces FOREWORD Suripto, SH Vice Chairman of 3rd Commission, Indonesian House of Representatives And Chariman of Lesperssi Founder Board Border issues have been one of the largest areas of concern for Indonesia. Since becoming a sovereign state 61 years ago, Indonesia is still facing a series of territorial border problems. Up until today, Indonesia has reached agreements with its neighbouring countries related to demarcation and state border delineation. However, the lack of an unequivocal authority for border management has left serious implications for the state’s sovereignty and its citizen’s security. The Indonesian border of today, is still having to deal with border crime, which includes the violation of the territorial border, smuggling and terrorist infiltration, illegal fishing, illegal logging and Human Rights violations. These kinds of violations have also made a serious impact on the state’s sovereignty and citizen’s security. As of today, Indonesia still has an ‘un-settled’ sea territory, with regard to the rights of sovereignty (Additional Zone, Economic Exclusive Zone, and continent plate). This frequently provokes conflict between the authorised sea-territory officer on patrol and foreign ships or fishermen from neighbouring countries. One of the principal border problems is the Sipadan-Ligitan dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia, which started in 1969. -

Defence and Security After Brexit Understanding the Possible Implications of the UK’S Decision to Leave the EU Compendium Report

Defence and security after Brexit Understanding the possible implications of the UK’s decision to leave the EU Compendium report James Black, Alex Hall, Kate Cox, Marta Kepe, Erik Silfversten For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1786 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: HMS Vanguard (MoD/Crown copyright 2014); Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4, A Chinook Helicopter of 18 Squadron, HMS Defender (MoD/Crown copyright 2016); Cyber Security at MoD (Crown copyright); Brexit (donfiore/fotolia); Heavily armed Police in London (davidf/iStock) RAND Europe is a not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Defence and security after Brexit Preface This RAND study examines the potential defence and security implications of the United Kingdom’s (UK) decision to leave the European Union (‘Brexit’). -

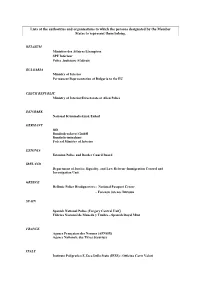

Lists of the Authorities and Organisations to Which the Persons Designated by the Member States to Represent Them Belong

Lists of the authorities and organisations to which the persons designated by the Member States to represent them belong. BELGIUM Ministère des Affaires Etrangères SPF Intérieur Police Judiciaire Fédérale BULGARIA Ministry of Interior Permanent Representation of Bulgaria to the EU CZECH REPUBLIC Ministry of Interior/Directorate of Alien Police DENMARK National Kriminalteknisk Enhed GERMANY BSI Bundesdruckerei GmbH Bundeskriminalamt Federal Ministry of Interior ESTONIA Estonian Police and Border Guard Board IRELAND Department of Justice, Equality, and Law Reform -Immigration Control and Investigation Unit GREECE Hellenic Police Headquarters - National Passport Center - Forensic Science Division SPAIN Spanish National Police (Forgery Central Unit) Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre - Spanish Royal Mint FRANCE Agence Françaises des Normes (AFNOR) Agence Nationale des Titres Sécurisés ITALY Instituto Poligrafico E Zeca Dello Stato (IPZS) - Officina Carte Valori CYPRUS Ministry of Foreign Affairs LATVIA Ministry of Interior - Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs Embassy of Latvia LITHUANIA Ministry of Foreign Affairs LUXEMBOURG Ministère des Affaires Etrangères HUNGARY Special service for national security MALTA Malta Information Technology Agency Ministry of Foreign Affairs NETHERLANDS Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken Ministerie van Justitie Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations AUSTRIA Österreichische Staatsdruckerei Abt. II/3 (Fremdenpolizeiangelegenheiten) POLAND Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Department of Consular Affairs -

After the Wall: the Legal Ramifications of the East German Border Guard Trials in Unified Germany Micah Goodman

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 29 Article 3 Issue 3 1996 After the Wall: The Legal Ramifications of the East German Border Guard Trials in Unified Germany Micah Goodman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Goodman, Micah (1996) "After the Wall: The Legal Ramifications of the East German Border Guard Trials in Unified Germany," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 29: Iss. 3, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol29/iss3/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES After the Wall: The Legal Ramifications of the East German Border Guard Trials in Unified Germany Micah Goodman* Introduction Since the reunification of East and West Germany in 1990, the German government' has tried over fifty2 former East German soldiers for shooting and killing East German citizens who attempted to escape across the East- West German border.3 The government has also indicted a dozen high- ranking East German government officials.4 The German government charged and briefly tried Erich Honecker, the leader of the German Demo- cratic Republic (G.D.R.) from 1971 to 1989, for giving the orders to shoot escaping defectors. 5 While on guard duty at the border between the two * Associate, Rogers & Wells; J.D., Cornell Law School, 1996; B.A., Swarthmore College, 1991. -

Memorial on Admissibility on Behalf of the Government of Ukraine

Ukraine v. Russia (re Eastern Ukraine) APPLICATION NO. 8019/16 Kyiv, 8 November 2019 MEMORIAL ON ADMISSIBILITY ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF UKRAINE CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1. The Russian Federation has consistently denied its involvement in the conflict in eastern Ukraine, and has sought to evade international legal responsibility by adopting a series of measures to disguise and “outsource” its military aggression in eastern Ukraine. The Kremlin’s denials of direct involvement were implausible from the outset, and were roundly rejected by the international community. All of the relevant international institutions rightly hold Moscow responsible for a pattern of conduct that has been designed to destabilise Ukraine by sponsoring separatist entities in the use of armed force against the legitimate Government and members of the civilian population. Almost from the outset, the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the European Union, and the G7 all re-affirmed Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognised borders, and condemned the Russian Federation’s continuing proxy war in eastern Ukraine. As the conflict has continued, the evidence of Russia’s direct and indirect involvement in the violent rebellion in Donbass has become more and more apparent. Despite Russia’s crude attempts to conceal its involvement, the proof of Russian State responsibility has steadily mounted. In the face of the obvious truth, Russia’s policy of implausible deniability has fallen apart completely. 2. Ukraine submits that the human rights violations committed by Russian forces and their proxies, as particularised in this application, fall directly within Russia’s extra-territorial jurisdiction for the purposes of article 1 of the Convention. -

BOMCA 9 Border Management Programme in Central Asia (9Th

1 BOMCA 9 Border Management Programme in Central Asia (9th phase) Newsletter №9 (2018) Programme is funded under the EU Development Co-operation Instrument (DCI) implementation of all planned BOMCA overview activities and allows us to reach the results this programme is aiming for. Since its launch in 2003, the various Now the project has reached the phases of the BOMCA programme stage where it is necessary to have focused on capacity building consider retrospectively and assess and institutional development, de- what has been done, how national veloping trade corridors, improving partners have built upon BOMCA border management systems and support (recommendations) to strenthen their institutional capacity, eliminating drug trafficking across and what is still is pending. BOMCA the Central Asian region. Each new management is very much looking phase of BOMCA has been designed forward to the upcoming Regional to gradually build upon and consoli- Steering Group meeting, which shall take place on 28 November in date the results achieved in the pre- Dushanbe, Tajikistan, where ceding phases. During its earlier discussion with beneficiary agencies phases, the programme channelled on the status of the implementation its resources towards creating mod- of provided recommendations is ern border management infrastruc- foresеen. ture in five Central Asian countries. Dear Friends, Maris Domins Capitalising on the success of previ- The 9th phase of BOMCA programme BOMCA Regional manager ous phases, this 9th phase intends to is extended until December 14th, In this edition continue interventions in the area of 2019— such a decision was made by : the European Commission and sup- institutional development, manage- ported by all five Central Asian States.