Summer 09.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14819/06 DCL 1 /Dl GSC.SMART.2.C Delegations Will Find Attached The

Council of the European Union Brussels, 1 August 2018 (OR. en) 14819/06 DCL 1 SCH-EVAL 177 FRONT 221 COMIX 916 DECLASSIFICATION of document: ST14819/06 RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED dated: 10 November 2006 new status: Public Subject: Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND : report on Land Borders Delegations will find attached the declassified version of the above document. The text of this document is identical to the previous version. 14819/06 DCL 1 /dl GSC.SMART.2.C EN RESTREINT COUNCIL OF Brussels, 10 November 2006 THE EUROPEAN UNION 14819/06 RESTREINT UE SCH-EVAL 177 FRONT 221 COMIX 916 REPORT from: the Land BordersEvaluation Committee to: the Schengen Evaluation Working Party Subject : Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND : report on Land Borders TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Management summary ............................................................................................................... 4 3. General information .................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. Strategy ............................................................................................................................. 5 3.2. Organisational (functional) structure ................................................................................ 9 3.3. Operational effectiveness ............................................................................................... -

024682/EU XXVI. GP Eingelangt Am 05/06/18

024682/EU XXVI. GP Eingelangt am 05/06/18 Council of the European Union Brussels, 5 June 2018 (OR. en) 8832/1/06 REV 1 DCL 1 SCH-EVAL 78 FRONT 89 COMIX 408 DECLASSIFICATION of document: ST8832/1/06 REV 1 RESTREINT UE/EU RESTRICTED dated: 20 July 2006 new status: Public Subject: Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND: report on Sea Borders Delegations will find attached the declassified version of the above document. The text of this document is identical to the previous version. 8832/1/06 REV 1 DCL 1 /dl DGF 2C EN www.parlament.gv.at RESTREINT UE COUNCIL OF Brussels, 20 July 2006 THE EUROPEAN UNION 8832/1/06 REV 1 RESTREINT UE SCH-EVAL 78 FRONT 89 COMIX 408 REPORT from: the Evaluation Committee Sea Borders to: the Schengen Evaluation Working Party Subject : Schengen evaluation of the new Member States - POLAND: report on Sea Borders This report was made by the Evaluation Committee Sea Borders and will be brought to the attention of the Sch-Eval Working Party which will ensure a report and the presentation of the follow-up thereto to the Council. 8832/1/06 REV 1 EB/mdc 1 DG H 2 RESTREINT UE EN www.parlament.gv.at RESTREINT UE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Management summary ............................................................................................................... 5 3. General information ................................................................................................................... -

Border Management Reform in Transition Democracies

Border Management Reform in Transition Democracies Editors Aditya Batara G Beni Sukadis Contributors Pierre Aepli Colonel Rudito A.A. Banyu Perwita, PhD Zoltán Nagy Lieutenant-Colonel János Hegedűs First Edition, June 2007 Layout Front Cover Lebanese-Israeli Borders Downloaded from: www.michaelcotten.com Printed by Copyright DCAF & LESPERSSI, 2007 The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces FOREWORD Suripto, SH Vice Chairman of 3rd Commission, Indonesian House of Representatives And Chariman of Lesperssi Founder Board Border issues have been one of the largest areas of concern for Indonesia. Since becoming a sovereign state 61 years ago, Indonesia is still facing a series of territorial border problems. Up until today, Indonesia has reached agreements with its neighbouring countries related to demarcation and state border delineation. However, the lack of an unequivocal authority for border management has left serious implications for the state’s sovereignty and its citizen’s security. The Indonesian border of today, is still having to deal with border crime, which includes the violation of the territorial border, smuggling and terrorist infiltration, illegal fishing, illegal logging and Human Rights violations. These kinds of violations have also made a serious impact on the state’s sovereignty and citizen’s security. As of today, Indonesia still has an ‘un-settled’ sea territory, with regard to the rights of sovereignty (Additional Zone, Economic Exclusive Zone, and continent plate). This frequently provokes conflict between the authorised sea-territory officer on patrol and foreign ships or fishermen from neighbouring countries. One of the principal border problems is the Sipadan-Ligitan dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia, which started in 1969. -

Defence and Security After Brexit Understanding the Possible Implications of the UK’S Decision to Leave the EU Compendium Report

Defence and security after Brexit Understanding the possible implications of the UK’s decision to leave the EU Compendium report James Black, Alex Hall, Kate Cox, Marta Kepe, Erik Silfversten For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1786 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: HMS Vanguard (MoD/Crown copyright 2014); Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4, A Chinook Helicopter of 18 Squadron, HMS Defender (MoD/Crown copyright 2016); Cyber Security at MoD (Crown copyright); Brexit (donfiore/fotolia); Heavily armed Police in London (davidf/iStock) RAND Europe is a not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Defence and security after Brexit Preface This RAND study examines the potential defence and security implications of the United Kingdom’s (UK) decision to leave the European Union (‘Brexit’). -

Memorial on Admissibility on Behalf of the Government of Ukraine

Ukraine v. Russia (re Eastern Ukraine) APPLICATION NO. 8019/16 Kyiv, 8 November 2019 MEMORIAL ON ADMISSIBILITY ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF UKRAINE CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1. The Russian Federation has consistently denied its involvement in the conflict in eastern Ukraine, and has sought to evade international legal responsibility by adopting a series of measures to disguise and “outsource” its military aggression in eastern Ukraine. The Kremlin’s denials of direct involvement were implausible from the outset, and were roundly rejected by the international community. All of the relevant international institutions rightly hold Moscow responsible for a pattern of conduct that has been designed to destabilise Ukraine by sponsoring separatist entities in the use of armed force against the legitimate Government and members of the civilian population. Almost from the outset, the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the European Union, and the G7 all re-affirmed Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognised borders, and condemned the Russian Federation’s continuing proxy war in eastern Ukraine. As the conflict has continued, the evidence of Russia’s direct and indirect involvement in the violent rebellion in Donbass has become more and more apparent. Despite Russia’s crude attempts to conceal its involvement, the proof of Russian State responsibility has steadily mounted. In the face of the obvious truth, Russia’s policy of implausible deniability has fallen apart completely. 2. Ukraine submits that the human rights violations committed by Russian forces and their proxies, as particularised in this application, fall directly within Russia’s extra-territorial jurisdiction for the purposes of article 1 of the Convention. -

The Tribal Factor in Managing the Yemeni-Saudi Border

FROM BORDERING TO ORDERING: THE TRIBAL FACTOR IN MANAGING THE YEMENI-SAUDI BORDER L ISA L ENZ -A YOUB Introduction This chapter aims at a closer consideration of the different border management practices at the Yemeni- Saudi border and its transformation throughout the 20 th century and until today. Particular attention will be paid to the shifting importance of the local tribes in managing the border. Thest century21 has marked the beginning of major changes in the tasks of the border shaykhs (tribal leaders) and their tribes, who have been responsible for the guarding and administering of the border from its initial establishment in 1934. Increasing Saudi security concerns, as well as the conflicts raging in northern Yemen, have contributed to the successive formalization, institutionalization and militarization of the Yemeni-Saudi border management at the expense of the long-standing role of the local tribes. Today, with the conflict-induced eviction of many shaykhs from their territories, the traditional system of tribal border protection has collapsed. By understanding the essence of border making as power strategy (Popescu 2012, 8), the chapter illustrates drastic power transformations in the securing of the Yemeni-Saudi border, shifting from relative tribal autonomy and responsibility, and close cooperation between tribe and state, towards the increasing exclusion of the border tribes from active bordering processes and practices. The theory of border studies has extensively addressed this phenomenon. In the 1990s, border studies faced a major paradigm shift that has led to the understanding of borders as processes or practices that can be produced by different actors on multiple levels. -

Crimea After the Georgian Crisis

Crimea after the Georgian Crisis Crimea After the Georgian Crisis Following the Georgian Crisis, there was frequent speculation in the international media Crimea theCrisis Georgian after about the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea as the next likely target of Russian military intervention. Logic suggests that Crimea, the only region in Ukraine with an ethnic Russian JAKOB HEDENSKOG majority, with its historical links to Russia and contested affiliation to Ukraine, and with its Hero City Sevastopol (the base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet), would be an easy target for the Kremlin’s neo-imperialist policy. This report aims to compare the situation around Crimea with that regarding South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which led to the Georgian Crisis. The main objective is to identify similarities and differences concerning both the situation on the ground and Russia’s policy towards the regions, in order to determine whether a military scenario for Crimea is impossible, Jakob Hedenskog possible or even likely. For a study (in Swedish) on the Georgian Crisis and its consequences, see Larsson, Robert L., et al. Det kaukasiska lackmustestet: Konsekvenser och lärdomar av det rysk-georgiska kriget i augusti 2008, FOI-R--2563--SE, september 2008. Front cover photo: The chief of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and the Chief of the Ukrainian Marine jointly celebrate the 60th Anniversary of Victory Day, 9 May 2005, © Jakob Hedenskog (2005) FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency, is a mainly assignment-funded agency under the Ministry of Defence. The core activities are research, method and technology development, as well as studies conducted in the interests of Swedish defence and the safety and security of society. -

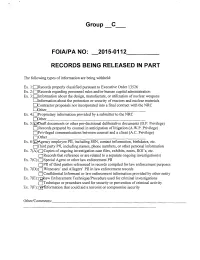

Final, Group C

Group C FOIA/PA NO: 2015-0112 "" RECORDS BEING RELEASED IN PART The following types of information are being withheld: Ex. 1:[--1 Records properly classified pursuant to Executive Order 13526 Ex. 2:L---] Records regarding personnel rules and/or humlan capital administration Ex. 3 :[• Information about the design, manufacture, or" utilization of nuclear weapons [--Information about the protection or security of reactors and nuclear materials [•Contractor proposals not incorporated into a final contract with the NRC [--Other Ex. 4:D-- Proprietary information provided by a submitter to the NRC E--Other Ex. 5 :[i-Draft documents or other pre-decisional deliberative documents (D.P. Privilege) E] Records prepared by counsel in anticipation of litigation (A.W.P. Privilege) D] Privileged communications between counsel and a client (A.C. Privilege) Eli Other Ex. 6:[•-Agency employee P1I, including SSN, contact information, birthdates, etc. •Third party P!I, including names, phone numbers, or other personal information Ex. 7(A):[--Copies of ongoing investigation case files, exhibits, notes, ROJ's, etc. D Records that reference or are related to a separate ongoing investigation(s) Ex. 7(C): [--Special Agent or other law enforcement P11 EI---PII of third parties referenced in records compiled for law enforcement purposes Ex. 7(D):D---Witnesses' and Allegers' P11 in law enforcement records [--Confidential Informant or law enforcement information provided by other entity Ex. 7(E): [•Eaw Enforcement Technique/Procedure used for criminal investigations [--Technique or procedure used for security or prevention of criminal activity Ex. 7(F): [•L'Tformation that could aid a terrorist or compromise security Other/Comments: Kiukan, Brett_________________ ______ From: Kiukan, Brett Sent: Thursday, October 30, 2014 10:5S2 AM To: Safford, Carrie; StAmour, Norman Subject: Drone Flyovers at Nuclear Power Plants Carrie & Norm, To set the scene a little bit: r've been asked to speak, as RI's regional counsel, at an upcoming NEL Lawyer meeting in Philly. -

United Kingdom Strategic Export Controls Annual Report 2011

United Kingdom Strategic Export Controls Annual Report 2011 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 10 of the Export Control Act 2002 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 July 2012 HC 337 London: The Stationery Office £x.xx © Crown copyright 2012 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www. nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This publication is available for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk ISBN: 9780102980066 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID P002500246 07/12 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Contents Ministerial Foreword 1 Section 1: Domestic Policy 3 Section 2: International Policy 14 Section 3: Export Licensing Decisions during 2010 26 Section 4: Military Equipment 39 Annexes Annex A The Consolidated EU and National Arms Export Licensing Criteria 41 Annex B International Development Association eligible countries 45 Annex C Information required for the UN Register of Conventional Arms 46 Ministerial Foreword This is the fifteenth Annual Report on Strategic Export As a direct result, Ministers now have increased Controls to be published by the United Kingdom. It oversight of export licence applications. -

Border Management and Migration Controls in Poland Working Papers

Working Papers Global Migration: Consequences and Responses Paper 2019/24, August 2019 Border Management and Migration Controls in Poland Research report Monika Szulecka Centre of Migration Research University of Warsaw © Monika Szulecka Reference: RESPOND 2.1 This research was conducted under the Horizon 2020 project ‘RESPOND Multilevel Governance oF MiGration and Beyond’ (770564). The sole responsibility For the content oF this publication lies with the author. The European Union is not responsible For any use that may be made oF the inFormation contained therein. Any enquiries reGardinG this report should be sent to: [email protected] This document is available For download at www.respondmiGration.com. Horizon 2020 RESPOND: Multilevel Governance oF MiGration and Beyond (770564) 2 3 Contents AcknowledGements 6 About the project 7 Executive summary 8 1. Introduction 10 2. Methodology 13 3. Developments since 2011 15 3.1 The development oF miGration and asylum policy 15 3.2 Selected leGal chanGes 17 4. Legal Framework 20 4.1 Pre-entry measures 20 4.1.1 Visas 20 4.1.2 Carrier sanction leGislation 23 4.1.3 Advance passenGer inFormation/ PassenGer Name inFormation 24 4.1.4 ImmiGration liaison oFFicers 26 4.2 Control at the border 27 4.2.1 The rules oF border crossinG and border checks 27 4.2.2 ReFusals oF entry 28 4.2.3 The use oF IT systems 29 4.2.4 Provisions reGardinG unlawFul border crossinG and security threats 30 4.2.5 Border surveillance 31 4.3 Internal controls 31 4.3.1 Control oF the leGality oF stay 31 4.3.2 Control oF the leGality oF work 33 4.3.3 SpeciFic permits For stay in Poland 33 4.4 Return, detention For return and readmission 35 4.4.1 Apprehension and detention 35 4.4.2 Returns oF third-country nationals 37 5. -

The Military's Role in Counterterrorism

The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hug etortThe LPapers The Military’s Role in Counterterrorism: Examples and Implications for Liberal Democracies Geraint Hughes Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. hes Strategic Studies Institute U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA The Letort Papers In the early 18th century, James Letort, an explorer and fur trader, was instrumental in opening up the Cumberland Valley to settlement. By 1752, there was a garrison on Letort Creek at what is today Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. In those days, Carlisle Barracks lay at the western edge of the American colonies. It was a bastion for the protection of settlers and a departure point for further exploration. Today, as was the case over two centuries ago, Carlisle Barracks, as the home of the U.S. Army War College, is a place of transition and transformation. In the same spirit of bold curiosity that compelled the men and women who, like Letort, settled the American West, the Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) presents The Letort Papers. This series allows SSI to publish papers, retrospectives, speeches, or essays of interest to the defense academic community which may not correspond with our mainstream policy-oriented publications. If you think you may have a subject amenable to publication in our Letort Paper series, or if you wish to comment on a particular paper, please contact Dr. Antulio J. Echevarria II, Director of Research, U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 632 Wright Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5046. -

The Invisible Exodus: North Koreans in the People’S Republic of China

NORTH KOREA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 14, No. 8 (C) – November 2002 I had seen almost four hundred North Koreans repatriated from China during my stay in Musan...It was so dangerous to cross the border, but I decided to cross it anyway. --North Korean who escaped to China THE INVISIBLE EXODUS: NORTH KOREANS IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] November 2002 Vol. 14, No. 8 (C) THE INVISIBLE EXODUS: NORTH KOREANS IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA I. Summary and Recommendations........................................................................................................................... 2 Overview................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Recommendations on the Refugee Crisis .............................................................................................................. 5 To North Korea.................................................................................................................................................. 5 To China ...........................................................................................................................................................