Reconciling the Civil War in Winslow Homer's Undertow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Winslow Homer : New

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART WINSLOW HOMER MEMORIAL EXHIBITION MCMXI CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER OF THIS CATALOGUE AN EDITION OF 2^00 COPIES WAS PRINTED FEBRUARY, I 9 I I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/catalogueofloaneOOhome FISHING BOATS OFF SCARBOROUGH BY WINSLOW HOMER LENT BY ALEXANDER W. DRAKE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER NEW YORK FEBRUARY THE SIXTH TO MARCH THE NINETEENTH MCMXI COPYRIGHT, FEBRUARY, I 9 I I BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART LIST OF LENDERS National Gallery of Art Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts The Lotos Club Edward D. Adams Alexander W. Drake Louis Ettlinger Richard H. Ewart Hamilton Field Charles L. Freer Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Alexander C. Humphreys John G. Johnson Burton Mansfield Randall Morgan H. K. Pomroy Mrs. H. W. Rogers Lewis A. Stimson Edward T. Stotesbury Samuel Untermyer Mrs. Lawson Valentine W. A. White COMMITTEE ON ARRANGEMENTS John W. Alexander, Chairman Edwin H. Blashfield Bryson Burroughs William M. Chase Kenyon Cox Thomas W. Dewing Daniel C. French Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Samuel Isham Roland F. Knoedler Will H. Low Francis D. Millet Edward Robinson J. Alden Weir : TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Frontispiece, Opposite Title-Page List of Lenders . Committee on Arrangements . viii Table of Contents .... ix Winslow Homer xi Paintings in Public Museums . xxi Bibliography ...... xxiii Catalogue Oil Paintings 3 Water Colors . • 2 7 Index ......... • 49 WINSLOW HOMER WINSLOW HOMER INSLOW HOMER was born in Boston, February 24, 1836. -

IOWNER of PROPERTY NAME Mr

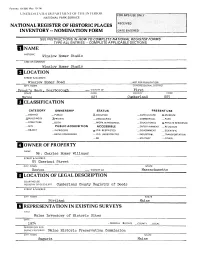

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATtS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Winslow Homer Road -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Front's Nerk, Scarborough — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maine 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X- p mVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER; IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY, TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Portland Maine El REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE -FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslow Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages -which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

Scribner's Magazine

SCRIBNER’S MAGAZINE January, 1911 Volume 49, Issue 1 Important notice The MJP’s digital edition of the January 1911 issue of Scribner’s Magazine (49:1) is incomplete. It lacks the front and back covers of the magazine, the magazine’s table of contents, and all of the advertising that, in a typical issue of the magazine, could run for a hundred pages and appeared both before and after the magazine contents reproduced below. Because we were unable to locate an intact copy of this magazine, we made our scan from a six-month volume of Scribner’s (kindly provided to us by the John Hay Library, at Brown), from which all advertising was stripped when it was initially bound many years ago. For a better sense of what this magazine originally looked like, please refer to any issue in our collection of Scribner’s except for the following five incomplete issues: December 1910, January 1911, August 1911, July 1912, and August 1912. If you happen to know where we may find an intact, cover-to-cover hard copy of any of these five issues, we would appreciate if you would contact the MJP project manager at: [email protected] Drawn by Blendon Campbell. SO THE SAD SHEPHERD THANKED THEM FOR THEIR ENTERTAINMENT AND TOOK THF LITTLE KID AGAIN IN HIS ARMS, AND WENT INTO THE NIGHT. —"The Sad Shepherd," page 7. SCRIBNER'S MAGAZINE VOL. XLIX JANUARY, 1911 NO. 1 THE SAD SHEPHERD BY HENRY VAX DYKE ILLUSTRATION* (FRONTISPIECE) BY BLENDON CAMPBELL I among the copses fell too far behind, he drew out his shepherd's pipe and blew a OUT of the Valley of Gardens, strain of music, shrill and plaintive, qua• where a film of new-fallen vering and lamenting through the hollow snow lay smooth as feathers night. -

The Story of Prouts Neck

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 1924 The Story of Prouts Neck Rupert Sargent Holland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Genealogy Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Rupert Sargent, "The Story of Prouts Neck" (1924). Maine Collection. 101. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/101 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ·THE STORY OF PROUTS NECK· BY RUPERT SARGENT HOLLAND .. THE PROUTS NECK ASSOCIATION PROUTS NECK, MAINE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF FRANK MOSS ARTIST AND DEVOTED WORKER FOR THE WELFARE OF PROUTS NECK .. Copyright 1924 by The Prouts Neck Association Prouts Neck, Me. Printed in U.S. A. THE COSMOS PRESS, INC., CAMBRIDGE, MASS. The idea of collecting and putting in book form sotrie of the interesting incidents in the history of Prouts Neck originated with Mr. Frank Moss, who some years ago printed for private distribution an account of the N~ck as it was in I886 and some of the changes that had since occurred. Copies of this pamphlet were rare, and Mr. Moss and some of his friends wished .to add other material of interest and bring it up to date, making a book that, published by the Prouts Neck Association, should interest summer residents ·in the story of this beautiful headland and in the endeavors to preserve its native charms. -

The Life and Works of Winslow Homer

i^','i yv^ ijj.B.CLARK£ cn Qni'5;tLL£RS«ST»Tm..ri THE LIFE AND WORKS OF WINSLOW HOMER PORTIL^IT OF WINSLOW HOMER AT THE AGE OF SEVENTY-TWO From a photograph taken at Prout's Neck, Maine, in igo8. Photogravure 1 y^ff THE'T'ttt:^ LIFEt ti AND WORKS OF WINSLOW HOMER BY WILLIAM HOWE DOWNES WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY 191 JNJMAA/j«^G LIBRARY JUL 19™ i5[!15WW OCT 2 :M332 iNSTITUTlOW HATiOMAL COLL^^iiuji Of FINE AHW COPYRIGHT^ J911, BY WILLIAM HOWE DOWNES ALL RIGHTS RESER\'ED Published October iqii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS THE author is grateful to all those persons who have aided him in the preparation of this biography. To Winslow Homer's two brothers he owes especially cordial thanks. Mr. Charles S. Homer has been most kind in lending indispensable assistance and most patient in an- swering questions. Mr. Arthur B. Homer with fortitude has listened to the reading of the entire manuscript, and has given wise and valuable counsel and criticism. To Mr. Arthur P. Homer and Mr. Charles Lowell Homer of Boston the author is indebted for many useful suggestions and interesting remi- niscences. Mr. Joseph E. Baker, the friend and comrade of Winslow Homer in his youth, and his fellow-apprentice in BufTord's lithographic establishment in Boston, from 185510 1857, has supplied interesting data which could have been obtained from no other source. Mr. Walter Rowlands, of the fine arts department of the Boston Public Library, has made himself useful in the line of historic research, for which his experience admirably qualifies him, and has gone over the first rough draft of the manuscript and offered many friendly hints and suggestions for its betterment. -

News Release the Metropolitan Museum of Art

news release The Metropolitan Museum of Art For Release: Immediate Contact: Harold Holzer Jill Schoenbach LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENTS OF WINSLOW HOMER ON VIEW AT METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Major Retrospective Exhibition Will Include Works in All Media Exhibition dates: June 20 - September 22,1996 Exhibition location: European Paintings Galleries, second floor Press preview: Monday, June 17,10 a.m. - noon The creative power and versatility of one of America's greatest painters will be on view in the major retrospective exhibition Winslow Homer, opening June 20 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The most comprehensive presentation of Homer's art in more than 20 years, the exhibition will include approximately 180 paintings, drawings, and watercolors, and will offer a broad vision of his achievements over five decades. The exhibition, which was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, comes to New York after showings at the National Gallery and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where it has been a great critical and popular success. The exhibition is made possible by GTE Corporation. Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum, commented: "Homer's wide-ranging pictorial style and technical virtuosity have earned him a place among the nation's indisputable masters. This summer, we are proud to display the full range of Homer's genius to visitors to the Museum from across America and around the world." "GTE is honored to join The Metropolitan Museum of Art in presenting Winslow Homer. GTE's involvement in this exhibition is a corollary to our role in communications. Our support of the arts and education reflects our desire to enhance the quality of life in our society, challenge the human spirit, and enjoy the product of creative genius," said Charles R. -

Artist Spotlight

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT Winslow Homer DAN SCOTT Illustrator,Winslow War Artist andHomer Master Painter Winslow Homer (1836 – 1910) was a remarkable American painter who mastered sev- eral mediums, including oils and watercolors. He lived a fascinating life; working as a commercial illustrator, an artist-correspondent for the Civil War, being published on commemorative stamps and achieving financial success as a fine artist. He did all this as a largely self-taught artist. In this ebook, I take a closer look at his life and art. Winslow Homer, Snap the Whip, 1872 2 Key Facts Here are some interesting facts about Winslow Homer: • He was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1836. From a young age, he was encour- aged to paint by his mother, who was a talented watercolor artist. • He started his career as an apprentice to a commercial lithographer. He then em- barked on a career as a commercial illustrator, which lasted for around 20 years. His work in illustration explains the distinct style of his paintings. • He was mostly self-taught, learning the fundamentals from his time as an appren- tice lithographer and commercial illustrator. But he did take a few art classes here and there. • American painter and teacher, Robert Henri, referred to Homer as an “integrity of nature”. • In 1962, Homer’s Breezing Up was featured on a commemorative stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office. That painting is now hanging in the National Gallery in Wash- ington DC. Winslow Homer, Breezing Up (A Fair Wind), 1876 3 Winslow Homer, Commemorative Stamp of 1962 • Homer was sent by Harper’s Magazine to the Civil War (1861 - 1865) as an art- ist-correspondent. -

Winslow Homer

TH E %ULF STREAM TH E METROP OLITAN MUSEUM O F A RT n n d ted H 1 9 nc s h i h inc s w . Sig ed a d a ; omer , 8 9 . Can vas , i he g , he ide WINSLOW HOMER %ENYON Cox NEW YOR% PRIVATELY PRINTED MCM% IV ”MO Co r h 1 1 py ig t 9 4. by Frederic Fairchdd Sh erman TO ITS F I RST READ ER PH IL I P LITTELL W H OSE CRITIC I SM AND AD VICE ON MATTERS O E STYLE W ERE I NVALUAB LE TO M E H B % F F T I S O O I S A ECTI ONATELY INSCRIB ED . PREFACE ' For the facts and dates ofHomer s life Iam indebt ed to “The Life and Works ofWinslow Homer by ll D Mifflin : Wi iam Howe ownes , Houghton Com 1 1 1 . pany , 9 From this book . which I have accepted th e nl sub edt as o y authority on the j . I have also bor ' “ rowed a few quotations from John W . Beatty s In % ’ ro r f t ducfto y Note and rom Homer s own letters . ’ For the interpretation I have put upon the facts , ' and for the attempt at a critical estimate of Homer s . t is art , I alone am responsible Upon the validi y ofth estimate my little book must depend for its excuse for being . But whil e the opin ions expressed are my own they must Often coincide with those expressed by r s did : other w iter . -

National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BREADTH AND MASTERY OF WINSLOW HOMER 'S ART ON EXHIBITION AT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART. OCTOBER 15. 1995 - JANUARY 28. 1996; PASSES REQUIRED ON WEEKENDS AND HOLIDAYS WASHINGTON, D.C., August 25, 1995 The towering artistic achievements of Winslow Homer (1836-1910), one of America's greatest painters, will be presented in the first comprehensive exhibition of his work in more than twenty years. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Winslow Homer will be on view in the Gallery's East Building from October 15, 1995 through January 28, 1996, before traveling to Boston and New York. The exhibition is made possible by GTE Corporation. More than 225 works in the show, including 86 oil paintings, 99 watercolors, 31 drawings, and six prints, as well as technical materials, will illustrate Homer's superb breadth, mastery, keen observation of life, and sensitivity to political issues in nineteenth-century America. "It is fitting that the premiere venue for this exhibition will be the capital of the nation whose life and finest values are so enduringly expressed in Homer's art," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "We are deeply grateful -more- Fourlli Street at Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 2056f) homer . page 2 to GTE for making this possible." "GTE is honored to join the National Gallery of Art for the ninth time in presenting a major exhibition. By supporting Winslow Homer, GTE affirms its belief in art as a powerful means of communication. We have a longstanding commitment to enhancing the quality of life in our society by supporting the arts and education," said Charles R. -

American Images of Childhood in an Age of Educational and Social

AMERICAN IMAGES OF CHILDHOOD IN AN AGE OF EDUCATIONAL AND SOCIAL REFORM, 1870-1915 By AMBER C. STITT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2013 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Amber C. Stitt, candidate for the PhD degree*. _________________Henry Adams________________ (chair of the committee) _________________Jenifer Neils_________________ _________________Gary Sampson_________________ _________________Renée Sentilles_________________ Date: March 8, 2013 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 Table of Contents: List of Figures 11. Acknowledgments 38. Abstract 41. Introduction 43. Chapter I 90. Nineteenth-Century Children’s Social Reform 86. The Cruel Precedent. 88. The Cultural Trope of the “Bad Boy” 92. Revelations in Nineteenth-Century Childhood Pedagogy 97. Kindergarten 90. Friedrich Froebel 91. Froebel’s American Champions 93. Reflections of New Pedagogy in Children’s Literature 104. Thomas Bailey Aldrich 104. Mark Twain 107. The Role of Gender in Children’s Literature 110. Conclusions 114. Chapter II 117. Nineteenth-Century American Genre Painters 118. Predecessors 118. Early Themes of American Childhood 120. The Theme of Family Affection 121. 4 The Theme of the Stages of Life 128. Genre Painting 131. George Caleb Bingham 131. William Sidney Mount 137. The Predecessors: A Summary 144. The Innovators: Painters of the “Bad Boy” 145. Eastman Johnson 146. Background 147. Johnson’s Early Images of Children 151. The Iconic Work: Boy Rebellion 160. Johnson: Conclusions 165. Winslow Homer 166. Background 166. -

Picture Study Portfolio: Homer Published by Simply Charlotte Mason Homer © 2017 by Emily Kiser

Simply Charlotte Mason presents Homer Picture Study Portfolios by Emily Kiser Simply Charlotte Mason presents Breathe a sigh of relief—you, the teacher, don't have to know about art in order to teach picture study! With Picture Study Portfolios you have everything you need to help your family enjoy and appreciate beautiful art. Just 15 minutes once a week and the Cassatt simple guidance in this book will inuence and enrich your children more than you can imagine. In this book you will nd • A living biography to help your child form a relation with the artist • Step-by-step instructions for doing picture study with the pictures in this portfolio • Helpful Leading oughts that will add to your understanding of each picture • Extra recommended books for learning more about the artist "We cannot measure the inuence that one or another artist has upon the child's sense of beauty, upon his power of seeing, as in a picture, the common sight of life; he is enriched more than we know in having really looked at even a single picture."—Charlotte Mason Simply Charlotte Maso.comn Picture St udy Portfolios Winslow Homer (1836–1910) by Emily Kiser To be used with the Picture Study Portfolio: Homer published by Simply Charlotte Mason Homer © 2017 by Emily Kiser All rights reserved. However, we grant permission to make printed copies or use this work on multiple electronic devices for members of your immediate household. Quantity discounts are available for classroom and co-op use. Please contact us for details. Cover Design: John Shafer ISBN 978-1-61634-404-7 printed ISBN 978-1-61634-405-4 electronic download Published by Simply Charlotte Mason, LLC 930 New Hope Road #11-892 Lawrenceville, Georgia 30045 simplycharlottemason.com Printed by PrintLogic, Inc. -

Winslow Homer Studio Stands on the South Side of Winslow Homer Road Above the Shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine

Form No 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) U Nil hDSIArhSUhPARTMhNTOMHh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBFR Winslov Homer Road __NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Prrmt.'s Tfenk , Scarborough —. VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Man np 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Portland Maine 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE .FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY ___LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslov Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries.