Winslow Homer Is “Both the Historian and the Poet of the Sea…” Wrote One Critic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rockwell Kent Collection

THE ROCKWELL KENT COLLECTION THE ROCKWELL KENT COLLECTION Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/rockwellkentcollOObowd THE ROCKWELL KENT COLLECTION BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART 1972 COPYRIGHT 1972 BY THE PRESIDENT AND TRUSTEES OF BOWDOIN COLLEGE BRUNSWICK, MAINE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER 72-93429 Acknowledgments HIS little catalogue is dedicated to Sally Kent in gratitude for her abiding interest and considerable help in the for- mation of this collection. With the aid of Mrs. Kent, and the support of a generous donor, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art was able to obtain a representative collec- tion of the work of the late Rockwell Kent, consisting of six paintings and eighty-two drawings and watercolors. This collection, in addition to the John Sloan collection and the Winslow Homer collection already established here, will provide both the general public and researchers the opportunity to see and study in great detail certain important aspects of American art in the early twentieth century. Our appreciation is also extended to Mr. Richard Larcada of the Larcada Galleries, New York City, for his help during all phases of selection and acquisition. R.V.W. [5] Introduction HE paintings, drawings and watercolors in this collection pro- vide a varied cross section of Rockwell Kent's activities as painter, draftsman and illustrator. They range over a wide variety of style and technique, from finished paintings and watercolors to sketches and notations intended for use in the studio. As such, they provide an insight, otherwise unavailable, into the artist's creative processes and methods. -

Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Winslow Homer : New

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART WINSLOW HOMER MEMORIAL EXHIBITION MCMXI CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER OF THIS CATALOGUE AN EDITION OF 2^00 COPIES WAS PRINTED FEBRUARY, I 9 I I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/catalogueofloaneOOhome FISHING BOATS OFF SCARBOROUGH BY WINSLOW HOMER LENT BY ALEXANDER W. DRAKE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER NEW YORK FEBRUARY THE SIXTH TO MARCH THE NINETEENTH MCMXI COPYRIGHT, FEBRUARY, I 9 I I BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART LIST OF LENDERS National Gallery of Art Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts The Lotos Club Edward D. Adams Alexander W. Drake Louis Ettlinger Richard H. Ewart Hamilton Field Charles L. Freer Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Alexander C. Humphreys John G. Johnson Burton Mansfield Randall Morgan H. K. Pomroy Mrs. H. W. Rogers Lewis A. Stimson Edward T. Stotesbury Samuel Untermyer Mrs. Lawson Valentine W. A. White COMMITTEE ON ARRANGEMENTS John W. Alexander, Chairman Edwin H. Blashfield Bryson Burroughs William M. Chase Kenyon Cox Thomas W. Dewing Daniel C. French Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Samuel Isham Roland F. Knoedler Will H. Low Francis D. Millet Edward Robinson J. Alden Weir : TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Frontispiece, Opposite Title-Page List of Lenders . Committee on Arrangements . viii Table of Contents .... ix Winslow Homer xi Paintings in Public Museums . xxi Bibliography ...... xxiii Catalogue Oil Paintings 3 Water Colors . • 2 7 Index ......... • 49 WINSLOW HOMER WINSLOW HOMER INSLOW HOMER was born in Boston, February 24, 1836. -

'Body' of Work from Artist and Athlete

3 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2009 Local CP The Star Art Adventure I Sam Dalkilic-Miestowski ‘Body’ of work from artist and athlete C R O W N P O I N T ver the past year the Steeple Gallery has exhibited the works froOm Chicago artist Christina STAR Body. Chicago native, Christina Body, received a MANAGING EDITOR Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in painting and Kimberley Mathisen minors in photography and theater from [email protected] Southern Illinois University, in Carbondale. She was also an art and athletic scholarship recipient at SIU. Classified and Subscriptions (219) 663-4212 FAX: (219) 663-0137 Office location 112 W. Clark Street Crown Point, IN 46307 ADVERTISING DEADLINES Display Friday 12:00 p.m. Classified Friday 12:00 p.m. Legals Friday 12:00 p.m. fascinated by the qualities of light and the end- less variations in color and temperature that it SUBSCRIPTIONS reveals. Painting en plein air is an emotional and spiritual experience. Capturing brilliant light and One year $26.00 its radiance in the natural and built world leaves School $20.00 me feeling clear, elated and ethereal all at the One year out of state $32.00 same time.” Body paints en plein air through the One year (foreign) $54.00 seasons in Chicago and also finds inspiration painting the tropics with extended stays in Jamaica, Key West, Florida and her travels abroad. Body’s award winning paintings have earned her participation in juried shows and national plein air painting competitions and invitational’s, including ‘2008 Door County Plein Air Festival, I N D E X Door County, Wis. -

Harn Museum of Art / Spring 2021

HARN MUSEUM OF ART / SPRING 2021 WELCOME BACK After closing to the public to prevent the spread welcoming space for all in 2021 while continuing to of COVID-19 in March and reopening in July with provide virtual engagement opportunities, such as precautions in place, the Harn Museum of Art Museum Nights, for UF students and community welcomed 26,685 visitors in 2020. It has been our members alike. pleasure to have our doors open to you at a time when the power of art is needed most and in our As we bring in 2021 and continue to celebrate our 30th Anniversary year. We are especially pleased to 30th Anniversary, we are pleased to announce the welcome UF students back to campus this semester acquisition of The Florida Art Collection, Gift of and to provide a safe environment to explore and Samuel H. and Roberta T. Vickers, which includes learn—whether in person or virtually—through more than 1200 works by over 700 artists given our collection. The Harn looks forward to being a as a generous donation by Florida’s own Sam and Robbie Vickers. As an integral part of the University of Florida 3 EXHIBITIONS campus, the Harn Museum of Art will utilize 10 ART FEATURE the Vickers’ gift as an important new resource to 11 CAMPUS AND strengthen faculty collaboration, support teaching COMMUNITY DESTINATION and enhance class tours, and provide research 13 VICKERS COLLECTION projects for future study. 22 TEACHING IN A PANDEMIC 23 ART KITS ENCOURAGE The collection presents a wonderful opportunity CREATIVITY for new and collection presents a wonderful 25 GIFT PLANNING opportunity for new and original student research 26 INSPIRED GIVING and internships across a variety of disciplines in 27 BEHIND THE COVER alignment with our Strategic Plan goals. -

IOWNER of PROPERTY NAME Mr

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATtS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Winslow Homer Road -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Front's Nerk, Scarborough — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maine 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X- p mVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER; IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY, TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Portland Maine El REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE -FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslow Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages -which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

Mythmakers: the Art of Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Mark Thistlethwaite, review of Mythmakers: The Art of Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11889. Mythmakers: The Art of Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington Curated by: Margaret C. Adler, Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, Jennifer R. Henneman, and Thomas Brent Smith Exhibition schedule: Denver Art Museum, June 26–September 7, 2020; Portland Museum of Art, September 25–November 29, 2020; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, December 22, 2020–February 28, 2021 Exhibition catalogue: Margaret C. Adler, Claire M. Barry, Adam Gopnik, Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, Jennifer R. Henneman, Janelle Montgomery, Thomas Brent Smith, and Peter G. M. Van de Moortel, Homer | Remington, exh. cat. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum of American Art; Denver: Denver Art Museum; Portland, ME: Portland Museum of Art, in association with Yale University Press, 2020. 224 pp.; 179 color illus.; Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780300246100) Reviewed by: Mark Thistlethwaite, Kay and Velma Kimbell Chair of Art History Emeritus, Texas Christian University Surprisingly, given the popular appeal of the art it presents, Mythmakers: The Art of Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington offers the first major museum exhibition to explore the similarities and differences in work by these “American Titans” (as an early working exhibition title styled them).1 Were it not for the pandemic, the exhibition, consisting of more than sixty artworks in a variety of media, would have undoubtedly attracted large, enthusiastic crowds to each of its three venues. -

Winslow Homer Lecture Series Pr

August 19, 2008 Press Release For Immediate Release Contact: Andrew E. Albertson, Curator of Education & Public Programs Phone: (518) 673-2314 x.109 Arkell Museum Begins Winslow Homer Lecture Series with Syracuse University Professor David Tatham CANAJOHARIE, NY—The Arkell Museum at Canajoharie announces a three-week Winslow Homer lecture series to complement “Winslow Homer Watercolors,” a temporary exhibition at the new museum. All lectures are on Tuesday evenings, August 26 through September 9, at 7pm. “Winslow Homer Watercolors” presents the Arkell Museum’s renowned collection of the artist’s breathtaking watercolors with highlights including Homework , Moonlight and On the Cliff . Visitors may also view the Museum’s six Homer oil paintings, which are on permanent display in the Arkell American Art Gallery. David Tatham, a Syracuse University Professor Emeritus of Art History who is a recognized Homer author and scholar, will begin the lecture series with “Winslow Homer at Work in New York State: A Bounty of Paintings” on Tuesday, August 26 at 7pm. Tatham has authored seven books and more than eighty scholarly articles, exhibition catalogue essays, and journal reviews concerning American art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He is known for his books on Homer, including: Winslow Homer in the Adirondacks ; Winslow Homer in the 1880s: Watercolors, Drawings, and Etchings ; Winslow Homer and the Illustrated Book ; and Winslow Homer and the Pictorial Press . Tatham’s lecture will focus on Homer’s paintings of New York State. On Tuesday, September 2, Robert Demarest will present “Traveling with Winslow Homer: America’s Premier Artist/Angler” at 7pm; he is the author of the book by the same name. -

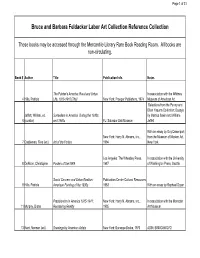

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S. -

Washington, D. C. June 1, 1967. the National Gallery Today Announced It

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215 extension 224 Washington, D. C. June 1, 1967. The National Gallery today announced it will lend 17 American paintings, including the work of Gilbert Stuart, Winslow Homer, and Rembrandt Peale, to the Mint Museum of Art in Charlotte for the inauguration of its new building this fall. John Walker, Director of the National Gallery said the paintings will be on view from September 15 to October 27. He called the opening of the new Mint Museum building a significant event for Charlotte and the Carolinas. Of foremost interest in the exhibition is Gilbert Stuart's portrait of Richard Yates. from the Andrew Mellon Collection, - 2 - and the colorful Allies Day, May 1917 by Childe Hassam. The Yates portrait was finished soon after Stuart returned from Dublin to begin his famous series of George Washington portraits. The Rembrandt Peale painting is of the artist's friend, Thomas Sully, an important American portraitist who was raised in South Carolina. The Winslow Homer painting shows a small boat being beached at sunset. In addition to six primitive American paintings by unknown 18th and 19th century limners, the exhibition will include the work of John James Audubon, Robert Henri, Charles Hofmann, Ammi Phillips, Jeremiah Theus, Ralph E. W. Earl, and Joseph Badger. Director Walker observed that the pictures "share the common value of presenting America as interpreted by artists in their own time." He also noted that a good many of the painters repre sented in the collection lived or worked in the South. -

Reconciling the Civil War in Winslow Homer's Undertow

Reconciling the Civil War in Winslow Homer’s Undertow Clara E. Barnhart Winslow Homer’s Undertow (1886), rendered primarily by the leading male, she reaches back with her right hand to in shades of blue and grey, depicts four figures emerging grip the rescue sled. With her left arm she tightly grasps her from an ocean (Figure 1). Upon first glance, and as it was companion, clasping her to her body, her left hand grazing perceived by contemporary viewers, Undertow might well her companion’s right which is swung around the lateral side seem to document superior masculine heroics. Surely the of her frame. Their embrace is insecure; the down-turned men’s verticality alerts us to their chief roles as rescuers of woman is in danger of tipping further to her right, her body the women they bracket. Erect and strong, they haul their weight slumped and precariously distributed along the length catch to shore while the women, victims in need of saving, of the other woman’s body. Save for the efforts of her female lie prostrate and sightless. However accurate this cursory ally to whom she clings, the down-turned woman appears to reading may be, it denies Undertow the complexity with have a perilous hold. Her closest male rescuer does little to which Homer infused it. This paper asserts that Undertow is rectify her unsteadiness, holding only the end of her fabric far more than the straightforward rescue scene nineteenth- bathing dress, or possibly the end lip of a rescue-sled cov- century critics assumed it to be. -

News Release the Metropolitan Museum of Art

news release The Metropolitan Museum of Art For Release: Immediate Contact: Harold Holzer Jill Schoenbach LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENTS OF WINSLOW HOMER ON VIEW AT METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Major Retrospective Exhibition Will Include Works in All Media Exhibition dates: June 20 - September 22,1996 Exhibition location: European Paintings Galleries, second floor Press preview: Monday, June 17,10 a.m. - noon The creative power and versatility of one of America's greatest painters will be on view in the major retrospective exhibition Winslow Homer, opening June 20 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The most comprehensive presentation of Homer's art in more than 20 years, the exhibition will include approximately 180 paintings, drawings, and watercolors, and will offer a broad vision of his achievements over five decades. The exhibition, which was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, comes to New York after showings at the National Gallery and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where it has been a great critical and popular success. The exhibition is made possible by GTE Corporation. Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum, commented: "Homer's wide-ranging pictorial style and technical virtuosity have earned him a place among the nation's indisputable masters. This summer, we are proud to display the full range of Homer's genius to visitors to the Museum from across America and around the world." "GTE is honored to join The Metropolitan Museum of Art in presenting Winslow Homer. GTE's involvement in this exhibition is a corollary to our role in communications. Our support of the arts and education reflects our desire to enhance the quality of life in our society, challenge the human spirit, and enjoy the product of creative genius," said Charles R. -

Artist Spotlight

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT Winslow Homer DAN SCOTT Illustrator,Winslow War Artist andHomer Master Painter Winslow Homer (1836 – 1910) was a remarkable American painter who mastered sev- eral mediums, including oils and watercolors. He lived a fascinating life; working as a commercial illustrator, an artist-correspondent for the Civil War, being published on commemorative stamps and achieving financial success as a fine artist. He did all this as a largely self-taught artist. In this ebook, I take a closer look at his life and art. Winslow Homer, Snap the Whip, 1872 2 Key Facts Here are some interesting facts about Winslow Homer: • He was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1836. From a young age, he was encour- aged to paint by his mother, who was a talented watercolor artist. • He started his career as an apprentice to a commercial lithographer. He then em- barked on a career as a commercial illustrator, which lasted for around 20 years. His work in illustration explains the distinct style of his paintings. • He was mostly self-taught, learning the fundamentals from his time as an appren- tice lithographer and commercial illustrator. But he did take a few art classes here and there. • American painter and teacher, Robert Henri, referred to Homer as an “integrity of nature”. • In 1962, Homer’s Breezing Up was featured on a commemorative stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office. That painting is now hanging in the National Gallery in Wash- ington DC. Winslow Homer, Breezing Up (A Fair Wind), 1876 3 Winslow Homer, Commemorative Stamp of 1962 • Homer was sent by Harper’s Magazine to the Civil War (1861 - 1865) as an art- ist-correspondent.