Transatlantica, 2 | 2006 How He Sees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOWNER of PROPERTY NAME Mr

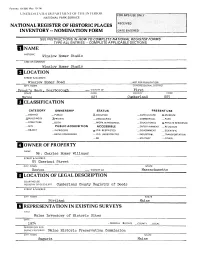

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATtS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Winslow Homer Road -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Front's Nerk, Scarborough — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maine 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X- p mVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER; IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY, TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Portland Maine El REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE -FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslow Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages -which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

Reconciling the Civil War in Winslow Homer's Undertow

Reconciling the Civil War in Winslow Homer’s Undertow Clara E. Barnhart Winslow Homer’s Undertow (1886), rendered primarily by the leading male, she reaches back with her right hand to in shades of blue and grey, depicts four figures emerging grip the rescue sled. With her left arm she tightly grasps her from an ocean (Figure 1). Upon first glance, and as it was companion, clasping her to her body, her left hand grazing perceived by contemporary viewers, Undertow might well her companion’s right which is swung around the lateral side seem to document superior masculine heroics. Surely the of her frame. Their embrace is insecure; the down-turned men’s verticality alerts us to their chief roles as rescuers of woman is in danger of tipping further to her right, her body the women they bracket. Erect and strong, they haul their weight slumped and precariously distributed along the length catch to shore while the women, victims in need of saving, of the other woman’s body. Save for the efforts of her female lie prostrate and sightless. However accurate this cursory ally to whom she clings, the down-turned woman appears to reading may be, it denies Undertow the complexity with have a perilous hold. Her closest male rescuer does little to which Homer infused it. This paper asserts that Undertow is rectify her unsteadiness, holding only the end of her fabric far more than the straightforward rescue scene nineteenth- bathing dress, or possibly the end lip of a rescue-sled cov- century critics assumed it to be. -

News Release the Metropolitan Museum of Art

news release The Metropolitan Museum of Art For Release: Immediate Contact: Harold Holzer Jill Schoenbach LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENTS OF WINSLOW HOMER ON VIEW AT METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Major Retrospective Exhibition Will Include Works in All Media Exhibition dates: June 20 - September 22,1996 Exhibition location: European Paintings Galleries, second floor Press preview: Monday, June 17,10 a.m. - noon The creative power and versatility of one of America's greatest painters will be on view in the major retrospective exhibition Winslow Homer, opening June 20 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The most comprehensive presentation of Homer's art in more than 20 years, the exhibition will include approximately 180 paintings, drawings, and watercolors, and will offer a broad vision of his achievements over five decades. The exhibition, which was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, comes to New York after showings at the National Gallery and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where it has been a great critical and popular success. The exhibition is made possible by GTE Corporation. Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum, commented: "Homer's wide-ranging pictorial style and technical virtuosity have earned him a place among the nation's indisputable masters. This summer, we are proud to display the full range of Homer's genius to visitors to the Museum from across America and around the world." "GTE is honored to join The Metropolitan Museum of Art in presenting Winslow Homer. GTE's involvement in this exhibition is a corollary to our role in communications. Our support of the arts and education reflects our desire to enhance the quality of life in our society, challenge the human spirit, and enjoy the product of creative genius," said Charles R. -

Artist Spotlight

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT Winslow Homer DAN SCOTT Illustrator,Winslow War Artist andHomer Master Painter Winslow Homer (1836 – 1910) was a remarkable American painter who mastered sev- eral mediums, including oils and watercolors. He lived a fascinating life; working as a commercial illustrator, an artist-correspondent for the Civil War, being published on commemorative stamps and achieving financial success as a fine artist. He did all this as a largely self-taught artist. In this ebook, I take a closer look at his life and art. Winslow Homer, Snap the Whip, 1872 2 Key Facts Here are some interesting facts about Winslow Homer: • He was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1836. From a young age, he was encour- aged to paint by his mother, who was a talented watercolor artist. • He started his career as an apprentice to a commercial lithographer. He then em- barked on a career as a commercial illustrator, which lasted for around 20 years. His work in illustration explains the distinct style of his paintings. • He was mostly self-taught, learning the fundamentals from his time as an appren- tice lithographer and commercial illustrator. But he did take a few art classes here and there. • American painter and teacher, Robert Henri, referred to Homer as an “integrity of nature”. • In 1962, Homer’s Breezing Up was featured on a commemorative stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office. That painting is now hanging in the National Gallery in Wash- ington DC. Winslow Homer, Breezing Up (A Fair Wind), 1876 3 Winslow Homer, Commemorative Stamp of 1962 • Homer was sent by Harper’s Magazine to the Civil War (1861 - 1865) as an art- ist-correspondent. -

National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BREADTH AND MASTERY OF WINSLOW HOMER 'S ART ON EXHIBITION AT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART. OCTOBER 15. 1995 - JANUARY 28. 1996; PASSES REQUIRED ON WEEKENDS AND HOLIDAYS WASHINGTON, D.C., August 25, 1995 The towering artistic achievements of Winslow Homer (1836-1910), one of America's greatest painters, will be presented in the first comprehensive exhibition of his work in more than twenty years. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Winslow Homer will be on view in the Gallery's East Building from October 15, 1995 through January 28, 1996, before traveling to Boston and New York. The exhibition is made possible by GTE Corporation. More than 225 works in the show, including 86 oil paintings, 99 watercolors, 31 drawings, and six prints, as well as technical materials, will illustrate Homer's superb breadth, mastery, keen observation of life, and sensitivity to political issues in nineteenth-century America. "It is fitting that the premiere venue for this exhibition will be the capital of the nation whose life and finest values are so enduringly expressed in Homer's art," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "We are deeply grateful -more- Fourlli Street at Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 2056f) homer . page 2 to GTE for making this possible." "GTE is honored to join the National Gallery of Art for the ninth time in presenting a major exhibition. By supporting Winslow Homer, GTE affirms its belief in art as a powerful means of communication. We have a longstanding commitment to enhancing the quality of life in our society by supporting the arts and education," said Charles R. -

American Images of Childhood in an Age of Educational and Social

AMERICAN IMAGES OF CHILDHOOD IN AN AGE OF EDUCATIONAL AND SOCIAL REFORM, 1870-1915 By AMBER C. STITT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2013 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Amber C. Stitt, candidate for the PhD degree*. _________________Henry Adams________________ (chair of the committee) _________________Jenifer Neils_________________ _________________Gary Sampson_________________ _________________Renée Sentilles_________________ Date: March 8, 2013 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 Table of Contents: List of Figures 11. Acknowledgments 38. Abstract 41. Introduction 43. Chapter I 90. Nineteenth-Century Children’s Social Reform 86. The Cruel Precedent. 88. The Cultural Trope of the “Bad Boy” 92. Revelations in Nineteenth-Century Childhood Pedagogy 97. Kindergarten 90. Friedrich Froebel 91. Froebel’s American Champions 93. Reflections of New Pedagogy in Children’s Literature 104. Thomas Bailey Aldrich 104. Mark Twain 107. The Role of Gender in Children’s Literature 110. Conclusions 114. Chapter II 117. Nineteenth-Century American Genre Painters 118. Predecessors 118. Early Themes of American Childhood 120. The Theme of Family Affection 121. 4 The Theme of the Stages of Life 128. Genre Painting 131. George Caleb Bingham 131. William Sidney Mount 137. The Predecessors: A Summary 144. The Innovators: Painters of the “Bad Boy” 145. Eastman Johnson 146. Background 147. Johnson’s Early Images of Children 151. The Iconic Work: Boy Rebellion 160. Johnson: Conclusions 165. Winslow Homer 166. Background 166. -

Picture Study Portfolio: Homer Published by Simply Charlotte Mason Homer © 2017 by Emily Kiser

Simply Charlotte Mason presents Homer Picture Study Portfolios by Emily Kiser Simply Charlotte Mason presents Breathe a sigh of relief—you, the teacher, don't have to know about art in order to teach picture study! With Picture Study Portfolios you have everything you need to help your family enjoy and appreciate beautiful art. Just 15 minutes once a week and the Cassatt simple guidance in this book will inuence and enrich your children more than you can imagine. In this book you will nd • A living biography to help your child form a relation with the artist • Step-by-step instructions for doing picture study with the pictures in this portfolio • Helpful Leading oughts that will add to your understanding of each picture • Extra recommended books for learning more about the artist "We cannot measure the inuence that one or another artist has upon the child's sense of beauty, upon his power of seeing, as in a picture, the common sight of life; he is enriched more than we know in having really looked at even a single picture."—Charlotte Mason Simply Charlotte Maso.comn Picture St udy Portfolios Winslow Homer (1836–1910) by Emily Kiser To be used with the Picture Study Portfolio: Homer published by Simply Charlotte Mason Homer © 2017 by Emily Kiser All rights reserved. However, we grant permission to make printed copies or use this work on multiple electronic devices for members of your immediate household. Quantity discounts are available for classroom and co-op use. Please contact us for details. Cover Design: John Shafer ISBN 978-1-61634-404-7 printed ISBN 978-1-61634-405-4 electronic download Published by Simply Charlotte Mason, LLC 930 New Hope Road #11-892 Lawrenceville, Georgia 30045 simplycharlottemason.com Printed by PrintLogic, Inc. -

Winslow Homer Studio Stands on the South Side of Winslow Homer Road Above the Shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine

Form No 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) U Nil hDSIArhSUhPARTMhNTOMHh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBFR Winslov Homer Road __NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Prrmt.'s Tfenk , Scarborough —. VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Man np 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Portland Maine 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE .FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY ___LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslov Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

Snap the Whip by Winslow Homer

Snap the Whip by Winslow Homer Print Facts • Medium: Oil on canvas • Date: 1872 • Size: 22” x 36” • Location: The Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. • Style: Realism • Genre: Genre Painting • Snap the whip was a popular children’s game in the 1800s and early 1900s. Children held hands tightly and then ran very fast. The first kids in line stop suddenly, yanking the other kids sideways. This causes the ones at the end to break free from the chain. Winning involved being the last person to not get broken from the chain. The painting portrays children playing this game in a landscape. • The historic painting depicts nine young boys playing the age-old game entitled ‘Snap the Whip’. The children are pulling and tugging each other back and forth, while the two at the end of the line have fallen over. The soft, glow of sunlight that peaks through the clouds illuminates their faces. Their clothing, more specifically their caps, suspenders, and short pants, reflects true late 1800 American attire. Featured in the background is the familiar little red schoolhouse; the school’s teachers in the distance are most likely meant to be supervising the usual recess activity. The scenic landscape of trees and wildflowers bordering a small field is so realistic that the viewer can almost hear the chirping of the birds and the buzzing of the insects. • ‘Snap the Whip’ was a huge success for the artist, and the painting was frequently reproduced. It was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. • Children embodied innocence and the promise of America's future and were depicted by many artists and writers during the 1870s. -

Winslow Homer Bio.Pdf

Snap the Whip Artist: Winslow Homer Created: 1872 Dimensions (cm): 91.4 x 55.9 Format: Oil on canvas Location: Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio, USA Perhaps Winslow Homer’s most beloved and popular painting was ‘Snap the Whip’, created with oil on canvas in 1872. The historic painting depicts nine young boys playing the age-old game entitled ‘Snap the Whip’. The children are pulling and tugging each other back and forth, while the two at the end of the line have fallen over. The soft, glow of sunlight that peaks through the clouds illuminates their faces. Their clothing, more specifically their caps, suspenders, and short pants, reflects true late 1800 American attire. Featured in the background is the familiar little red school house; the school teachers in the distance are most likely meant to be supervising the usual recess activity. The scenic landscape of trees and wildflowers bordering a small field is so realistic that the viewer can almost hear the chirping of the birds and the buzzing of the insects. Winslow Homer created a second, much smaller version of this painting, replacing the mountain range in the background with a wide, blue sky. ‘Snap the Whip’ was a huge success for the artist, and the painting was frequently reproduced. It was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Analysis and Reviews Robert Hughes (Nothing If Not Critical: Selected Essays on Art and Artists) once said, “Some major artists create popular stereotypes that last for decades; others never reach into popular culture at all. Winslow Homer was a painter of the first kind. -

Homer, Winslow (1836-1910) by Richard G

Homer, Winslow (1836-1910) by Richard G. Mann Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com One of the most prolific and important American painters and printmakers of the second half of the nineteenth century, Winslow Homer created a distinctly American, modern classical style. For this and other reasons, his works have often been compared to the achievements of such prominent nineteenth-century American authors as Henry Thoreau, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman. Homer dealt with many of the same themes that these writers did, including the Winslow Homer and heroism displayed by ordinary individuals, when confronted by seemingly insuperable three of his paintings: difficulties; the camaraderie and friendships enjoyed by soldiers and working men; The Herring Net, Undertow, and Rum Cay. and the isolation of the individual in the face of the "Other." Northwestern University Library Art Collection. Education and Early Career Born in Boston on February 24, 1836, Homer was initially trained as an artist by his mother, Henrietta Benson Winslow, who successfully exhibited watercolors of flowers and other still life subjects throughout her adult life. Between 1855 and 1857, he was apprenticed to John H. Bufford, a nationally prominent commercial artist, based in Boston; with this training, he began to do free-lance work for Harper's Weekly and other magazines. Aspiring to establish himself in the fine art world, he moved in 1859 to New York where he took painting lessons and began to exhibit drawings and paintings of urban scenes (for example, Skating in Central Park, 1860, shown at the National Academy of Design, April, 1860). -

WINSLOW HOMER an American Painter

WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter Dr. Ufuk ÇETİN WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter Author: Ufuk Çetin ORCID (0000-0001-5102-8183) ISBN: 978-625-7729-02-4 E-ISBN: 978-625-7729-03-1 First Edition: September 2020 © 2020 Efe Akademi. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mecha- nical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or a magazine. LIBRARY CATALOG ÇETİN, Ufuk Winslow Homer An American Painter First Edition, p. 71 , 135 x 195 mm. Keywords: 1. Painting, 2. American Painting Art, 3. .19th Century, 4. Landscape Painting, 5. Sea Painting. Graphic Design: İsa Burak GÜNGÖR ([email protected]) Cover Design: Duygu DÜNDAR ([email protected]) Certificate No: 43370 Printing House Certificate No: 43370 Efe Akademi Yayınevi Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Davutpaşa Kampüsiçi Esenler / İSTANBUL +90212 482 22 00 www.efeakademi.com Printing House: Ofis2005 Fotokopi ve Büro Makineleri San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Davutpaşa Kampüsiçi Esenler / İSTANBUL +90212 483 13 13 www.ofis2005.com WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter This book was written by me for my respected Professor Dr. Engin Beksaç for all his researches and studies in all forms of art through great passion just a present. Dr. Ufuk Çetin 20.09.2020 3 Ufuk Çetin 4 WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 11 HIS CHILDHOOD AND ARTISTIC CAREER ........ 18 SOME EXAMPLES FROM HIS PAINTINGS.........