Winslow Homer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Trier Scobol Solo 2014 Round 6

New Trier Scobol Solo 2014 PORTA Round 6 NIGRA 1. The speaker of this poem mentions men who “would have the rabbit out of hiding” in order to “please the yelping dogs”. The speaker states that he has “come after” those men and “made repair”. This is the first poem after the introductory “The Pasture” in the collection North of Boston. The speaker of this poem describes the boulders that he and another man encounter, stating that “some are loaves and some so nearly balls.” Its first line begins “Something there is that doesn’t love. .” A man in this poem repeats the lines “Good fences make good neighbors.” Name this poem by Robert Frost. Answer: “Mending Wall” 2. Two boys wearing straw hats lay on the grass and stare off into the distance in this painter’s Boys in a Pasture. Several crows try to attack a red animal running through the snow in another painting by this artist. Several boys hold hands while playing the title game in one of his paintings. This painter of The Fox Hunt and Snap the Whip showed a sailboat called the Gloucester [GLAO-stur] carrying four people through the windy seas in Breezing Up. Another seascape by this artist depicts a black sailor on a tilting boat surrounded by sharks. Name this American artist of The Gulf Stream. Answer: Winslow Homer [accept Boys in a Pasture before “this painter’s”] 3. Many Syrian and Lebanese businessmen in this country live in the suburb Pétionville [pet-yohn-veel] or the port Les Cayes [lay kay]. -

Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Winslow Homer : New

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART WINSLOW HOMER MEMORIAL EXHIBITION MCMXI CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER OF THIS CATALOGUE AN EDITION OF 2^00 COPIES WAS PRINTED FEBRUARY, I 9 I I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/catalogueofloaneOOhome FISHING BOATS OFF SCARBOROUGH BY WINSLOW HOMER LENT BY ALEXANDER W. DRAKE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER NEW YORK FEBRUARY THE SIXTH TO MARCH THE NINETEENTH MCMXI COPYRIGHT, FEBRUARY, I 9 I I BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART LIST OF LENDERS National Gallery of Art Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts The Lotos Club Edward D. Adams Alexander W. Drake Louis Ettlinger Richard H. Ewart Hamilton Field Charles L. Freer Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Alexander C. Humphreys John G. Johnson Burton Mansfield Randall Morgan H. K. Pomroy Mrs. H. W. Rogers Lewis A. Stimson Edward T. Stotesbury Samuel Untermyer Mrs. Lawson Valentine W. A. White COMMITTEE ON ARRANGEMENTS John W. Alexander, Chairman Edwin H. Blashfield Bryson Burroughs William M. Chase Kenyon Cox Thomas W. Dewing Daniel C. French Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Samuel Isham Roland F. Knoedler Will H. Low Francis D. Millet Edward Robinson J. Alden Weir : TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Frontispiece, Opposite Title-Page List of Lenders . Committee on Arrangements . viii Table of Contents .... ix Winslow Homer xi Paintings in Public Museums . xxi Bibliography ...... xxiii Catalogue Oil Paintings 3 Water Colors . • 2 7 Index ......... • 49 WINSLOW HOMER WINSLOW HOMER INSLOW HOMER was born in Boston, February 24, 1836. -

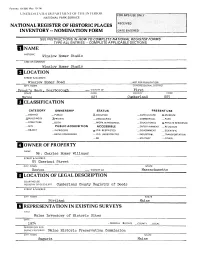

IOWNER of PROPERTY NAME Mr

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATtS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Winslow Homer Road -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Front's Nerk, Scarborough — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maine 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X- p mVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER; IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY, TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Portland Maine El REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE -FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslow Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages -which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

Reconciling the Civil War in Winslow Homer's Undertow

Reconciling the Civil War in Winslow Homer’s Undertow Clara E. Barnhart Winslow Homer’s Undertow (1886), rendered primarily by the leading male, she reaches back with her right hand to in shades of blue and grey, depicts four figures emerging grip the rescue sled. With her left arm she tightly grasps her from an ocean (Figure 1). Upon first glance, and as it was companion, clasping her to her body, her left hand grazing perceived by contemporary viewers, Undertow might well her companion’s right which is swung around the lateral side seem to document superior masculine heroics. Surely the of her frame. Their embrace is insecure; the down-turned men’s verticality alerts us to their chief roles as rescuers of woman is in danger of tipping further to her right, her body the women they bracket. Erect and strong, they haul their weight slumped and precariously distributed along the length catch to shore while the women, victims in need of saving, of the other woman’s body. Save for the efforts of her female lie prostrate and sightless. However accurate this cursory ally to whom she clings, the down-turned woman appears to reading may be, it denies Undertow the complexity with have a perilous hold. Her closest male rescuer does little to which Homer infused it. This paper asserts that Undertow is rectify her unsteadiness, holding only the end of her fabric far more than the straightforward rescue scene nineteenth- bathing dress, or possibly the end lip of a rescue-sled cov- century critics assumed it to be. -

The Story of Prouts Neck

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 1924 The Story of Prouts Neck Rupert Sargent Holland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Genealogy Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Rupert Sargent, "The Story of Prouts Neck" (1924). Maine Collection. 101. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/101 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ·THE STORY OF PROUTS NECK· BY RUPERT SARGENT HOLLAND .. THE PROUTS NECK ASSOCIATION PROUTS NECK, MAINE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF FRANK MOSS ARTIST AND DEVOTED WORKER FOR THE WELFARE OF PROUTS NECK .. Copyright 1924 by The Prouts Neck Association Prouts Neck, Me. Printed in U.S. A. THE COSMOS PRESS, INC., CAMBRIDGE, MASS. The idea of collecting and putting in book form sotrie of the interesting incidents in the history of Prouts Neck originated with Mr. Frank Moss, who some years ago printed for private distribution an account of the N~ck as it was in I886 and some of the changes that had since occurred. Copies of this pamphlet were rare, and Mr. Moss and some of his friends wished .to add other material of interest and bring it up to date, making a book that, published by the Prouts Neck Association, should interest summer residents ·in the story of this beautiful headland and in the endeavors to preserve its native charms. -

Artist Spotlight

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT Winslow Homer DAN SCOTT Illustrator,Winslow War Artist andHomer Master Painter Winslow Homer (1836 – 1910) was a remarkable American painter who mastered sev- eral mediums, including oils and watercolors. He lived a fascinating life; working as a commercial illustrator, an artist-correspondent for the Civil War, being published on commemorative stamps and achieving financial success as a fine artist. He did all this as a largely self-taught artist. In this ebook, I take a closer look at his life and art. Winslow Homer, Snap the Whip, 1872 2 Key Facts Here are some interesting facts about Winslow Homer: • He was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1836. From a young age, he was encour- aged to paint by his mother, who was a talented watercolor artist. • He started his career as an apprentice to a commercial lithographer. He then em- barked on a career as a commercial illustrator, which lasted for around 20 years. His work in illustration explains the distinct style of his paintings. • He was mostly self-taught, learning the fundamentals from his time as an appren- tice lithographer and commercial illustrator. But he did take a few art classes here and there. • American painter and teacher, Robert Henri, referred to Homer as an “integrity of nature”. • In 1962, Homer’s Breezing Up was featured on a commemorative stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office. That painting is now hanging in the National Gallery in Wash- ington DC. Winslow Homer, Breezing Up (A Fair Wind), 1876 3 Winslow Homer, Commemorative Stamp of 1962 • Homer was sent by Harper’s Magazine to the Civil War (1861 - 1865) as an art- ist-correspondent. -

National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BREADTH AND MASTERY OF WINSLOW HOMER 'S ART ON EXHIBITION AT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART. OCTOBER 15. 1995 - JANUARY 28. 1996; PASSES REQUIRED ON WEEKENDS AND HOLIDAYS WASHINGTON, D.C., August 25, 1995 The towering artistic achievements of Winslow Homer (1836-1910), one of America's greatest painters, will be presented in the first comprehensive exhibition of his work in more than twenty years. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Winslow Homer will be on view in the Gallery's East Building from October 15, 1995 through January 28, 1996, before traveling to Boston and New York. The exhibition is made possible by GTE Corporation. More than 225 works in the show, including 86 oil paintings, 99 watercolors, 31 drawings, and six prints, as well as technical materials, will illustrate Homer's superb breadth, mastery, keen observation of life, and sensitivity to political issues in nineteenth-century America. "It is fitting that the premiere venue for this exhibition will be the capital of the nation whose life and finest values are so enduringly expressed in Homer's art," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "We are deeply grateful -more- Fourlli Street at Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 2056f) homer . page 2 to GTE for making this possible." "GTE is honored to join the National Gallery of Art for the ninth time in presenting a major exhibition. By supporting Winslow Homer, GTE affirms its belief in art as a powerful means of communication. We have a longstanding commitment to enhancing the quality of life in our society by supporting the arts and education," said Charles R. -

Winslow Homer Studio Stands on the South Side of Winslow Homer Road Above the Shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine

Form No 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) U Nil hDSIArhSUhPARTMhNTOMHh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBFR Winslov Homer Road __NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Prrmt.'s Tfenk , Scarborough —. VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Man np 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Portland Maine 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE .FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY ___LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslov Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

PICTURING an INTRO– DUCTION Rachael Z

PICTURING AN INTRO– DUCTION Rachael Z. DeLue Picturing: An Introduction In the early 1880s, the American artist Winslow Homer (1836–1910) sketched a tragic scene: a capsized boat foundering near a rocky shore lined with trees. At least one figure appears to be floating in the water while others clutch at the overturned boat or take refuge on a rock. The hand of a drowning man claws the air, straining against the ocean’s relentless heave and pull (fig. 1). The graphite sketch, a study for Homer’s watercolor The Ship’s Boat (1883), is rough and summary, supplying just enough detail to communicate the bare facts of the event.1 The brusque, stuttering strokes of the pencil that delineate the swirl of the water and the broken snapping of sailcloth, along with the spiking slashes of graphite that designate the trees along the rocky ridge, broadcast the panic and chaos of the wreck. Sweeping pencil strokes in the sky that take the form of funnel clouds suggest the violence of the storm that overtook the boat; together with the wind-whipped trees, these cyclones evoke the destructive force of a hurricane. Homer’s sketch of a shipwreck reflects the sharp seaward turn his art took in the 1880s, after living nearly two years in Cullercoats, an English fishing village on the North Sea, and then settling for good in Prout’s Neck, Maine, a peninsula about ten miles north of Portland. Fishermen bravely pursuing their catch, wives stoically mending nets and tending to the day’s haul, calamitous storms, dramatic rescues, outsize waves crashing against rocky shores and exploding skyward Winslow Homer, The Fog Warning before making their retreat: Homer’s pictures during this period (detail, see fig. -

Winslow Homer Bio.Pdf

Snap the Whip Artist: Winslow Homer Created: 1872 Dimensions (cm): 91.4 x 55.9 Format: Oil on canvas Location: Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio, USA Perhaps Winslow Homer’s most beloved and popular painting was ‘Snap the Whip’, created with oil on canvas in 1872. The historic painting depicts nine young boys playing the age-old game entitled ‘Snap the Whip’. The children are pulling and tugging each other back and forth, while the two at the end of the line have fallen over. The soft, glow of sunlight that peaks through the clouds illuminates their faces. Their clothing, more specifically their caps, suspenders, and short pants, reflects true late 1800 American attire. Featured in the background is the familiar little red school house; the school teachers in the distance are most likely meant to be supervising the usual recess activity. The scenic landscape of trees and wildflowers bordering a small field is so realistic that the viewer can almost hear the chirping of the birds and the buzzing of the insects. Winslow Homer created a second, much smaller version of this painting, replacing the mountain range in the background with a wide, blue sky. ‘Snap the Whip’ was a huge success for the artist, and the painting was frequently reproduced. It was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Analysis and Reviews Robert Hughes (Nothing If Not Critical: Selected Essays on Art and Artists) once said, “Some major artists create popular stereotypes that last for decades; others never reach into popular culture at all. Winslow Homer was a painter of the first kind. -

Homer, Winslow (1836-1910) by Richard G

Homer, Winslow (1836-1910) by Richard G. Mann Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com One of the most prolific and important American painters and printmakers of the second half of the nineteenth century, Winslow Homer created a distinctly American, modern classical style. For this and other reasons, his works have often been compared to the achievements of such prominent nineteenth-century American authors as Henry Thoreau, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman. Homer dealt with many of the same themes that these writers did, including the Winslow Homer and heroism displayed by ordinary individuals, when confronted by seemingly insuperable three of his paintings: difficulties; the camaraderie and friendships enjoyed by soldiers and working men; The Herring Net, Undertow, and Rum Cay. and the isolation of the individual in the face of the "Other." Northwestern University Library Art Collection. Education and Early Career Born in Boston on February 24, 1836, Homer was initially trained as an artist by his mother, Henrietta Benson Winslow, who successfully exhibited watercolors of flowers and other still life subjects throughout her adult life. Between 1855 and 1857, he was apprenticed to John H. Bufford, a nationally prominent commercial artist, based in Boston; with this training, he began to do free-lance work for Harper's Weekly and other magazines. Aspiring to establish himself in the fine art world, he moved in 1859 to New York where he took painting lessons and began to exhibit drawings and paintings of urban scenes (for example, Skating in Central Park, 1860, shown at the National Academy of Design, April, 1860). -

WINSLOW HOMER an American Painter

WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter Dr. Ufuk ÇETİN WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter Author: Ufuk Çetin ORCID (0000-0001-5102-8183) ISBN: 978-625-7729-02-4 E-ISBN: 978-625-7729-03-1 First Edition: September 2020 © 2020 Efe Akademi. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mecha- nical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or a magazine. LIBRARY CATALOG ÇETİN, Ufuk Winslow Homer An American Painter First Edition, p. 71 , 135 x 195 mm. Keywords: 1. Painting, 2. American Painting Art, 3. .19th Century, 4. Landscape Painting, 5. Sea Painting. Graphic Design: İsa Burak GÜNGÖR ([email protected]) Cover Design: Duygu DÜNDAR ([email protected]) Certificate No: 43370 Printing House Certificate No: 43370 Efe Akademi Yayınevi Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Davutpaşa Kampüsiçi Esenler / İSTANBUL +90212 482 22 00 www.efeakademi.com Printing House: Ofis2005 Fotokopi ve Büro Makineleri San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Davutpaşa Kampüsiçi Esenler / İSTANBUL +90212 483 13 13 www.ofis2005.com WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter This book was written by me for my respected Professor Dr. Engin Beksaç for all his researches and studies in all forms of art through great passion just a present. Dr. Ufuk Çetin 20.09.2020 3 Ufuk Çetin 4 WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 11 HIS CHILDHOOD AND ARTISTIC CAREER ........ 18 SOME EXAMPLES FROM HIS PAINTINGS.........