©2012 Diana Bramham ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden State Patriot a Newsletter of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of California

Golden State Patriot A Newsletter of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of California Spring www.srcalifornia.com 2007 Golden State Patriot Why We Celebrate Patriots Day The “shot heard 'round the world” continues to reverberate each April as the members of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of California gather to celebrate“Patriots Day” in honor of those who participated in the battles and skirmishes that began our fight for independence. Yes, we continue to take our “Patriots Day” observance seriously here in California. This year, like in years past, the Sons of the Revolution will commemorate the battles of Lexington and Concord during our Patriots Day CONTENTS Luncheon on Saturday, April 21. Patriots Day Most Americans have lost sight of this annual celebration. Here in President’s Message California, few even know of its celebration or the events surrounding the Washington’s Birthday Reception Patriots Day observance. Fraunces Tavern Museum Nevertheless, it was on the night of April 18, 1775, that, approximately 700 Annual Membership Luncheon British soldiers had gathered on Boston Common to prepare for a raid on A Tribute to a President American military arms and supplies stored in nearby Concord, that patriots Historian’s Corner Paul Revere and William Dawes, both residents of Boston, set out to warn John Austin Stevens - Founder their fellow colonists. Over the next 24 hours, a series of events ensued The Gift of History which took Massachusetts and the other twelve colonies one step closer to Society Welcomes Members Independence. Modernization Project Completed Washington - Braddock Campaign On the fateful morning of April 19, 1775, American colonists prepared to Roster of Officers and Directors confront the soldiers of the British Army who were soon to arrive at the Meeting Schedule Massachusetts town of Lexington. -

A North Carolina Monastery

1 ?*,-&. XXIX. FEBRUARY, ,1893. No. 2. MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN HISTORY -•€*"..- & 'S>**&% A MONTHLY ILLUSTRATED JOURNAL AMi >2s2yj ftMJR DOLLARS TH1HTT FIVE CENTS PER ANNUM PER COPYy THE 'paniV' 5^. NewYorK Copyright, 1893, by National History Company. — : — —— — JOSEPH GILLOTT'S STEEL PENS THE MOST PERFECT OF PENS. * a. m 2 The most important literary event of the season. New York Advertiser. en SSI - to NOW READY. THE THIRD VOLUME OF THE 7& Memorial History of the Qty of New York. f The Most Elaborate "Work Ever Prepared on an American City. To be completed in four royal octavo volumes of about 6oo pages each and illustrated with not less than iooo portraits, views of historic houses, scenes, statues, tombs, monu- ments, maps, and fac-similes of autographs and ancient documents. The work will be printed by the De Vinne Press, which is equivalent to saying that so far as presswork, illustrations and general manufacture are concerned it will be unsurpassed by any publication ever issued in New York. The entire work will be edited by Gen. James Grant Wilson, with the co-operation of the following well-known and scholarly writers, all of whom will contribute one or more chapters Mr. Moncure D. Conway. Mr. William Nelson. Hon. Charles P. Daly. Bishop Henry C. Potter. Gen. Emmons Clark. Gen. T. F. Rodenbough, U.S.A. Rev. B. F. De Costa, D.D. Hon. Theodore Roosevelt. Rev. Morgan Dix, S.T.D. Mr. Edward Manning Ruttenber. Mr. Berthold Fernow. Mr. Frederick Saunders. Mr. Robert Ludlow Fowler. Mr. John Austin Stevens. Hon. James W. -

Site/Non-Site Explores the Relationship Between the Two Genres Which the Master of Aix-En- Provence Cultivated with the Same Passion: Landscapes and Still Lifes

site / non-site CÉZANNE site / non-site Guillermo Solana Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid February 4 – May 18, 2014 Fundación Colección Acknowledgements Thyssen-Bornemisza Board of Trustees President The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Hervé Irien José Ignacio Wert Ortega wishes to thank the following people Philipp Kaiser who have contributed decisively with Samuel Keller Vice-President their collaboration to making this Brian Kennedy Baroness Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza exhibition a reality: Udo Kittelmann Board Members María Alonso Perrine Le Blan HRH the Infanta Doña Pilar de Irina Antonova Ellen Lee Borbón Richard Armstrong Arnold L. Lehman José María Lassalle Ruiz László Baán Christophe Leribault Fernando Benzo Sáinz Mr. and Mrs. Barron U. Kidd Marina Loshak Marta Fernández Currás Graham W. J. Beal Glenn D. Lowry HIRH Archduchess Francesca von Christoph Becker Akiko Mabuchi Habsburg-Lothringen Jean-Yves Marin Miguel Klingenberg Richard Benefield Fred Bidwell Marc Mayer Miguel Satrústegui Gil-Delgado Mary G. Morton Isidre Fainé Casas Daniel Birnbaum Nathalie Bondil Pia Müller-Tamm Rodrigo de Rato y Figaredo Isabella Nilsson María de Corral López-Dóriga Michael Brand Thomas P. Campbell Nils Ohlsen Artistic Director Michael Clarke Eriko Osaka Guillermo Solana Caroline Collier Nicholas Penny Marcus Dekiert Ann Philbin Managing Director Lionel Pissarro Evelio Acevedo Philipp Demandt Jean Edmonson Christine Poullain Secretary Bernard Fibicher Earl A. Powell III Carmen Castañón Jiménez Gerhard Finckh HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco Giancarlo Forestieri William Robinson Honorary Director Marsha Rojas Tomàs Llorens David Franklin Matthias Frehner Alejandra Rossetti Peter Frei Katy Rothkopf Isabel García-Comas Klaus Albrecht Schröder María García Yelo Dieter Schwarz Léonard Gianadda Sir Nicholas Serota Karin van Gilst Esperanza Sobrino Belén Giráldez Nancy Spector Claudine Godts Maija Tanninen-Mattila Ann Goldstein Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza Michael Govan Charles L. -

1856 2 Jean Baptiste Du Tertre, “Indigoterie”

iLLusTRaTions Plates (Appear after page 204) 1 Anonymous, Johnny Heke (i.e., Hone Heke), 1856 2 Jean Baptiste Du Tertre, “Indigoterie” (detail), 1667 3 Anonymous, The Awakening of the Third Estate, 1789 4 José Campeche, El niño Juan Pantaleón de Avilés de Luna, 1808 5 William Blake, God Writing on the Tablets of the Covenant, 1805 6 James Sawkins, St. Jago [i.e., Santiago de] Cuba, 1859 7 Camille Pissarro, The Hermitage at Pontoise, 1867 8 Francisco Oller y Cestero, El Velorio [The Wake], 1895 9 Cover of Paris-Match 10 Bubbles scene from Rachida, 2002 11 Still of Ofelia from Pan’s Labyrinth, 2006 figures 1 Marie- Françoise Plissart from Droit de regards, 1985 2 2 Jean-Baptiste du Tertre, “Indigoterie,” Histoire générale des Antilles Habitées par les François, 1667 36 3 Plan of the Battle of Waterloo 37 4 John Bachmann, Panorama of the Seat of War: Bird’s Eye View of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and the District of Columbia, 1861 38 Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/chapter-pdf/651991/9780822393726-ix.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 5 “Multiplex set” from FM- 30–21 Aerial Photography: Military Applications, 1944 39 6 Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, Master Sergeant Steve Horton, U.S. Air Force 40 7 Anonymous, Toussaint L’Ouverture, ca. 1800 42 8 Dupuis, La Chute en masse, 1793 43 9 Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Untitled [Slaves, J. J. Smith’s Plantation near Beaufort, South Carolina], 1862 44 10 Emilio Longoni, May 1 or The Orator of the Strike, 1891 45 11 Ben H’midi and Ali la Pointe from The Battle of Algiers, 1966 46 12 An Inconvenient Truth, 2006 47 13 “Overseer,” detail from Du Tertre, “Indigoterie” 53 14 Anthony Van Dyck, Charles I at the Hunt, ca. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Winslow Homer : New

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART WINSLOW HOMER MEMORIAL EXHIBITION MCMXI CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER OF THIS CATALOGUE AN EDITION OF 2^00 COPIES WAS PRINTED FEBRUARY, I 9 I I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/catalogueofloaneOOhome FISHING BOATS OFF SCARBOROUGH BY WINSLOW HOMER LENT BY ALEXANDER W. DRAKE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER NEW YORK FEBRUARY THE SIXTH TO MARCH THE NINETEENTH MCMXI COPYRIGHT, FEBRUARY, I 9 I I BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART LIST OF LENDERS National Gallery of Art Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts The Lotos Club Edward D. Adams Alexander W. Drake Louis Ettlinger Richard H. Ewart Hamilton Field Charles L. Freer Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Alexander C. Humphreys John G. Johnson Burton Mansfield Randall Morgan H. K. Pomroy Mrs. H. W. Rogers Lewis A. Stimson Edward T. Stotesbury Samuel Untermyer Mrs. Lawson Valentine W. A. White COMMITTEE ON ARRANGEMENTS John W. Alexander, Chairman Edwin H. Blashfield Bryson Burroughs William M. Chase Kenyon Cox Thomas W. Dewing Daniel C. French Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Samuel Isham Roland F. Knoedler Will H. Low Francis D. Millet Edward Robinson J. Alden Weir : TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Frontispiece, Opposite Title-Page List of Lenders . Committee on Arrangements . viii Table of Contents .... ix Winslow Homer xi Paintings in Public Museums . xxi Bibliography ...... xxiii Catalogue Oil Paintings 3 Water Colors . • 2 7 Index ......... • 49 WINSLOW HOMER WINSLOW HOMER INSLOW HOMER was born in Boston, February 24, 1836. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

Valley Forge Map

Episode 7, 2012: Valley Forge Map Ruth Taylor: I'm Ruth Taylor. I'm the Executive Director of the Newport Historical Society in Rhode Island. It has about 10,000 objects, documenting Newport history from 1640, literally, until today. John Austin Stevens was actually a New Yorker who ended up dying in Newport. His papers were donated to us by his daughter in the 1940's. All kinds of bits and pieces. And then we noticed this obviously older paper. When we unfolded it, the hair stood up on the back of my neck. I could see the Schuylkill River labeled, and it became clear that it was a map of Washington's encampment at Valley Forge. My very first thought was, "Do people know about this? Is this what it appears to be?" Wes Cowan: Well, let's – let's take a look at what you've got here. I'm – I'm pretty excited about this. Schuylkill River. Ruth: Here, take a look over here. Wes: Valley Forge River... Wow. Ruth: And there's the actual forge, right there. Wes: You’re telling me that this is the plan of the camp at Valley Forge. Ruth: Well, it appears to be. Wes: What do you know about where it came from? Ruth: It was found with the John Austin Stevens papers. He was a descendent of a Continental Army officer. He became fascinated with the American Revolution. Wes: How long have you had it? Ruth: Well, we've had it since the 1940's, but apparently we've only known about it since I found it last summer. -

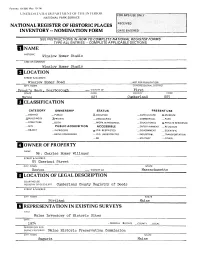

IOWNER of PROPERTY NAME Mr

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATtS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Winslov Homer Studio AND/OR COMMON Winslov Homer Studio LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Winslow Homer Road -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Front's Nerk, Scarborough — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maine 02^ Cumberland 005 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) JXPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X- p mVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER; IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Charles Homer Willauer STREET & NUMBER 85 Chestnut Street CITY, TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Cumberland County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Portland Maine El REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Maine Inventory of Historic Sites DATE -FEDERAL 2LSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Maine Historic Preservation Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta Maine DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Winslow Homer Studio stands on the south side of Winslow Homer Road above the shore of Prout's Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Winslow Homer Road is a private way serving a number of substantial summer cottages -which appear to date from the late 19th through the mid-20th centuries. -

For Immediate Release Media

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACTS: Kathleen Brady Stimpert, 512-475-6784, [email protected] Stacey Kaleh, 512-471-8433, [email protected] EXHIBITION SPOTLIGHTING PIONEERING PUERTO RICAN IMPRESSIONIST FRANCISCO OLLER TO PREMIERE AT THE BLANTON MUSEUM Works By Oller, Cézanne, Monet, Pissarro, and Other Masters Provide Window into Nineteenth-Century International Modernism Impressionism and the Caribbean: Francisco Oller and His Transatlantic World June 14 – September 6, 2015 AUSTIN, Texas – March 25, 2015 – The Blanton Museum of Art at The University of Texas at Austin presents Impressionism and the Caribbean: Francisco Oller and His Transatlantic World, an exhibition of approximately eighty paintings by Realist-Impressionist painter Francisco Oller (1833– 1917) and his contemporaries. Organized by the Brooklyn Museum and debuting at the Blanton, the exhibition reveals Oller’s important contributions to both the Paris avant-garde and the Puerto Rican school of painting. Providing historical, geographic, and cultural context for Oller’s work, the exhibition also features paintings by nineteenth-century masters Paul Cézanne, Winslow Homer, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and others. The Blanton’s presentation also includes a small selection of works by contemporaneous Texas artists working on both sides of the Atlantic. One of the most distinguished transatlantic painters of his day, Oller helped transform painting in the Caribbean. Over the course of his career, he traveled between Europe and Puerto Rico, spending considerable time in Paris. With each trip home, Oller brought with him the latest concepts and elements of early European modernism⎯including tenets of Realism and Impressionism⎯and combined them with the artistic styles and traditions of San Juan, revolutionizing the school of painting in Puerto Rico and throughout the Caribbean region. -

Expresiones Del Arte Puertorriqueño

Requisite for A Major Qualifying Proyect: MQP Expresiones del arte Puertorriqueño Written by ___________________ Marisol Erazo [email protected] ____________________ Submitted to: Professor Angel Rivera DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND ARTS WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE WORCESTER, MA 01609-2280 February, 2008 Tabla de Contenido Tabla de contenido .............................................................................................................. 1 Abstracto ............................................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 Influencia expresada en el arte puertorriqueño 3 Teoría sobre la función del arte 4 Un poco de historia 6 Discusión 10 Los primeros siglos coloniales 10 Discusión de la historia en el arte y su proposito expresado a traves de los artistas. José Campeche- 11 o Su vida y su introducción de la historia en la pintura 12 Francisco Oller 18 Miguel Pou 26 Ramón Frade 30 Myrna Báez 36 Conclusión ........................................................................................................................ 42 ……………………………………………………………………………..44 Referencias……………………………………………………………………………….45 46 Lista de Figuras…………………………………………………………………………. 47 2 Abstracto Los artistas puertorriqueños han contribuido con su trabajo a la cultura desde los siglos dieciocho y diecinueve. Un periodo particularmente importante comienza en los años 1800 y -

S1679 John Kersey

Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension Declaration of John Kersey S1679 f16VA Transcribed and annotated by Roy Randolph March 09, 2012 [Methodology: Spelling, punctuation and/or grammar have been corrected in some instances for ease of reading. A bracketed question mark [?] indicates that the word or words preceding it represent(s) a guess by me. Not all the material in the Pension File is included in the transcription.] State of Tennessee, Warren County On this the 5th day of February 1833 personally appeared in open court before the honorable James C. Mitchell the presiding judge of the Warren County Circuit Court now sitting, John Kersey, a resident of the county of Warren and state of Tennessee aged 75 years who being first duly sworn according to law doth, on his oath, make the following declaration in order to obtain the benefit of an Act of Congress passed 7th June 1832. That he entered the service of the United States under the following named officers and served as herein stated. In the latter part of 1774 or of the first part of 1775 it was believed by the citizens of Virginia that Lord Dunmore meditated some violence against them to oppose which a great number of the militia were called into the service and ordered to march towards Williamsburg in that state. Applicant was called into the service by what he understood to be a draft in Charlotte County in Va. and was attached to Captain Josiah Mourton’s [sic, corrected to Morton throughout] company. He was mustered into the service at Prince Edward Courthouse.