Middle-Out for Millennials Creating Jobs for Young People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Service Year a Cultural Expectation, a Common Opportunity, and a Civic Rite of Passage for Every Young American

A SERVICE YEAR A CULTURAL EXPECTATION, A COMMON OPPORTUNITY, AND A CIVIC RITE OF PASSAGE FOR EVERY YOUNG AMERICAN THE VISION The Franklin Project envisions a future in which a year of full-time national service — a service year — is a cultural expectation, a common opportunity, and a civic rite of passage for every young American. Each person can fulfill his or her national service obligation by joining the military or by completing a full-time civilian service year through programs such as Teach for America, AmeriCorps, and the Peace Corps, or any eligible nonprofit. A modest living allowance would be provided for the service year, which would be completed at some point between the ages of 18-28. THEORY OF THE FRANKLIN PROJECT We believe that spending a year in full-time service is a transformative experience for young citizens and future leaders. We’re focused on promoting a service year as a civic rite of passage because it will connect individuals to something bigger than themselves and to the idea that citizenship requires more from each of us than is currently expected. A generation of Americans spending a year in full-time service will unleash a reservoir of human capital to tackle pressing social challenges, unite diverse Americans in common purpose, and cultivate the next generation of leaders. HOW IT WILL WORK: A NEW RITE OF PASSAGE INTO ADULTHOOD RECRUIT SERVE CONNECT ATTRACTRECRUIT YOUNG PEOPLE TO THE PLACE 18- TO 28- YEAR-OLDS INTO ATTACH FULL-TIME SERVICE TO SERVICE YEAR EXPERIENCE SERVICE YEAR POSITIONS EMPLOYMENT AND EDUCATION CONTEXT In 2011, AmeriCorps CONTEXT Nonprofits and federal, CONTEXT Service years are an asset had 580,000 applications for 80,000 state, and local governments to career and adult development, positions, and studies show recognize national service as a rather than an interruption — and that millennials are increasingly cost-effective solution to meet their service year alumni make better inclined to serve, volunteering at missions, and colleges have already employees and more mature students. -

Steve, Attached You Will Find an Agenda for the 3

Steve, Attached you will find an agenda for the 3 day leadership training I received as part of the Aspen Institute/Franklin Project Ambassador/Fellowship. I was recently selected as an Ambassador/Fellow. The fellowship is an unpaid year-long fellowship supported by the Aspen Institute to promote National service which includes service in the Military and Public Service. 50 Ambassadors/Fellows were chosen from across the United States and all Ambassadors were at the 3 day training. I previously served in two Americorps programs; City Year and Public Allies. The Franklin Project envisions a future in which a year of full-time national service is a cultural expectation, a common opportunity, and a civic rite of passage for every young American. The Aspen Institute/Franklin Project Aspen Institute (Ambassadors) is leading the effort to improve citizenship by giving every young person in America the opportunity to serve. Sometime between the ages of 18 and 28, the young person would do a fully paid, full-time year of service in one of an array of areas, including health, poverty, conservation, or education. These young people will not only do good work and solve problems, but they will also become better young Americans. Let me know if you have any questions. Mark Payne Franklin Project Ambassadors Program Training and Seminar Agenda June 22-24, 2015 Alexandria, VA Monday 22 June 2015 12:30 – 1:00 pm Arrival Participants arrive at McChrystal Group Headquarters. Snacks and mingling. 1:00 – 1:15 pm Kickoff Welcome, objectives of the training, agenda review, logistics review. -

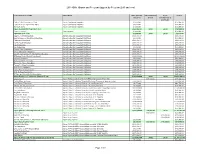

2015 Transparency Report

2015 Gifts, Grants and Program Support by Program (25K and over) CONSTITUENT NAME PROGRAM GIFT/GRANT ANONYMOUS NON- TOTAL AMOUNT GIFTS CHARITABLE SUPPORT Coulter 2006 Management Trust Aspen Community Programs $25,000.00 $25,000.00 Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund Aspen Community Programs $68,000.00 $68,000.00 Murdock, Jerry Aspen Community Programs $75,000.00 $75,000.00 Aspen Community Programs Total $168,000.00 $0.00 $0.00 $168,000.00 Resnick, Lynda R. Administration $75,000.00 $75,000.00 Administration Total $75,000.00 $0.00 $0.00 $75,000.00 Annie E. Casey Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $600,000.00 $600,000.00 Bank of America Charitable Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $50,000.00 $50,000.00 California Endowment Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $250,000.00 $250,000.00 Casey Family Programs Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $300,000.00 $300,000.00 Ford Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $400,000.00 $400,000.00 Gap Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $50,000.00 $50,000.00 Greater Texas Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $100,000.00 $100,000.00 Helios Education Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $400,000.00 $400,000.00 John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $100,000.00 $100,000.00 JPMorgan Chase Global Philanthropy Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $2,000,000.00 $2,000,000.00 Lumina Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $50,000.00 $50,000.00 Starbucks Coffee Company Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $100,000.00 $100,000.00 Marguerite Casey Foundation Aspen Forum for Community Solutions $125,000.00 $125,000.00 Conrad N. -

Franklin Project's Plan of Action

Generi Corp Inc Management Report Table of Contents A Declaration of Service 1 Executive Summary 5 A Plan of Action: A 21st Century National Service System 12 Core Elements of a 21st Century National Service System 12 Pathways to Engage More Americans in National Service 22 A Talent Pipeline through National Service 25 The Case for National Service 28 National Service to Address National Challenges 33 Conclusion 38 Acknowledgments 38 Endnotes 39 A Declaration of Service We, the undersigned, endorse the Franklin Project's Plan of Action to establish a 21st Century National Service System in America that inspires and engages at least one million young adults annually from all socio- economic backgrounds in a demanding year of full-time national service as a civic rite of passage to unleash the energy and idealism of each generation to address our nation’s challenges. General Stanley McChrystal Michael Brown Leadership Council Chair, The Franklin Project; U.S. Co-Founder and CEO, City Year Army General (Retired); Former Commander, International Security Assistance Force & U.S. Forces Afghanistan Anna Burger Former Secretary-Treasurer, SEIU; Former Chair, Change to Win Madeleine Albright Chair, Albright Stonebridge Group; Former U.S. Secretary of State & U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Barbara Bush Co-Founder and CEO, Global Health Corps Don Baer Worldwide Chair and CEO, Burson-Marsteller; Former Jean Case White House Director of Strategic Planning and CEO, The Case Foundation; Former Chair, President's Communications Council on Service and Civic Participation Melody Barnes Ray Chambers Chair, Aspen Forum for Community Solutions and UN Secretary General's Special Envoy for Financing of Opportunity Youth Incentive Fund; Vice Provost for the Health Related Millennium Development Goals & for Global Student Leadership Initiatives, New York Malaria; Co-Founder, America's Promise Alliance; Chair, University; Former Director, White House Domestic The MCJ Amelior Foundation Policy Council AnnMaura Connolly Samuel R. -

Corporation for National and Community Service Minutes of the Board of Directors Meeting October 3, 2016 3:05 P.M

Corporation for National and Community Service Minutes of the Board of Directors Meeting October 3, 2016 3:05 p.m. – 3:52 p.m., ET The Board of Directors for the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) convened in Washington, DC. The following members of the Board were present: Shamina Singh, Chair Rick Christman (by telephone) Mona Dixon (by telephone) Chair’s Opening Remarks Board Chair Shamina Singh called the meeting to order and welcomed everyone joining by phone and those gathered in person at the CNCS Headquarters. She welcomed her fellow Board members Rick Christman and Mona Dixon; Vice Chair Dean Reuter, Eric Liu, and Victoria Hughes were unavailable for the meeting. She extended greetings to those observing Rosh Hashanah and thanked Board members for participating in CNCS activities and events. She stated that Eric participated in an event in Washington State that showcased the Social Innovation Fund, and will be on hand for that state’s annual AmeriCorps induction later this month, when 1,000 new members will be sworn in. She also stated that Mona recently did a site visit to the Maricopa Integrated Health Systems in Arizona, and Victoria attended some of the Social Innovation Fund convening last month. Ms. Singh invited members of the public, on behalf of the Board, to comment on the business of the Board. Ms. Singh noted that the Board met via conference call last week. During the call, Wendy Spencer gave a detailed CEO report, which she will share today. Jeff Page, the Chief Operations Officer, gave an update on operations and our Enterprise Risk Management strategy. -

Challenge to Presidential Candidates

ow more than ever, America needs citizens • Establish service year opportunities as a of all backgrounds who are willing to come pathway to higher education and careers together and tackle the many problems facing by increasing education awards and loan Nour communities. We can start by offering every forgiveness for those who serve, making those young American the opportunity to complete a education awards tax-free, creating incentives service year, which will help solve today’s challenges for higher education institutions to recognize and prepare tomorrow’s leaders. and reward service years, and recruiting service year alumni into federal jobs. A service year is a substantial, sustained, full-time commitment that is supported with a modest living • Encourage states, communities, and nonprofit allowance and other benefits. It is organized to have organizations to create service year positions to a real, measurable community impact while making a solve locally identified problems by partnering lasting difference in the lives of those who serve. with the Service Year Exchange, a new private sector technology platform designed to Today, there are approximately 65,000 full-time connect individuals who want to serve with service year opportunities, including national service certified publicly and privately funded service positions that receive federal funding through year positions. AmeriCorps, the Peace Corps, and YouthBuild – Service year opportunities have a bipartisan programs where corps members help students in presidential and congressional legacy, enjoy low-income schools succeed, preserve national parks, overwhelming support from American voters of all fight poverty, and rebuild neighborhoods in the wake party affiliations, are sought by young adults, and of natural disasters. -

Workforce Development Strategy

AP PHOTO/J. SCOTT APPLEWHITE SCOTT PHOTO/J. AP Utilizing National Service as a 21st Century Workforce Strategy for Opportunity Youth By Tracey Ross, Shirley Sagawa, and Melissa Boteach March 2016 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Utilizing National Service as a 21st Century Workforce Strategy for Opportunity Youth By Tracey Ross, Shirley Sagawa, and Melissa Boteach March 2016 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 5 Workers facing barriers to employment 9 Benefits of national service to disadvantaged workers 11 The existing foundation for national service 16 Why now is the time to grow national service as a workforce development strategy 20 Recommendations 28 Conclusion 30 Endnotes Introduction and summary At the height of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC, as part of the New Deal. The CCC pro- vided critically needed jobs to unskilled young men while implementing a natural resource conservation program on public lands across the country.1 Over the course of nine years, nearly 3 million young men participated in the CCC, earning wages, food, shelter, and skills while planting more than 3 billion trees, combating forest fires, and providing aid in the wake of natural disasters.2 Today, national service programs—voluntary programs supported through publicly and privately funded stipends and designed to foster leadership through sustained service that meets public needs—have played a critical role in the lives of millions of Americans. Over the past 50 years, leaders from both sides of the aisle have supported service to meet goals of national significance. As a result, national service has been instru- mental in tackling important challenges facing families and communities, such as addressing underperforming schools and rehabilitating housing for low-income families. -

Bold Beginnings Bright Future Jack Miller Center 2013 Annual Report

Bold Beginnings Bright Future Jack Miller Center 2013 Annual Report Interview with University of Oklahoma President David Boren, page 18 Bold Beginnings Bright Future Our Mission “Educate and inform the The Jack Miller Center partners with whole mass of the people. They faculty, administrators, and donors to are the only sure reliance for transform student access to education in the preservation of our liberty.” American political thought and history, an Thomas Jefferson education that is necessary for informed and engaged citizenship. Jefferson’s words embody our mis- sion to revitalize education in Amer- ican political thought and history. It is in this spirit that we aim to provide students with the knowledge neces- sary for informed civic engagement, to ensure for all of us a future that upholds the freedoms envisioned by our nation’s founders. CONTENTS On the Cover: Executive Summary 4 JMC Partner Programs 6 Steven Smith, co-director of Commercial Republic Initiative 10 the Yale Center for the Study Summer Institutes 14 of Representative Institutions; Thomas Smith Q&A 16 Pamela Edwards, JMC director David Boren Q&A 18 of academic programs; and JMC Postdoctoral Fellowships 22 Thomas Smith, JMC board member and managing partner National & Regional Initiatives 26 of Prescott Investments. See JMC Leadership 30 Q&A with Mr. Smith regarding his Financials 33 philanthropy on page 16. Message from Jack Miller 34 2 Jack miller center 2013 Annual report Who We Are Why We Exist Too few professors teach—and too few students learn—about the princi- ples that sustain our free institutions and the history of our nation’s strug- gle to realize the promise of the Declaration of Independence and maintain our constitutional safeguards. -

Fall 2013 Serve Illinois Newsletter

State of Illinois Pat Quinn, Governor Department of Human Services Michelle Saddler, Secretary Fall 2013 National Service Programs Gather in Springfield for Recognition Day The 2013 Illinois National Service Recognition Day was held on October 8, 2013, at the Prairie Capital Convention Center and the State Capitol in Springfield. Nearly 1,000 AmeriCorps and Senior Corps members from across the state took part in the event, which recognized programs and energized members for the upcoming service year. The celebration began with lunch at the Prairie Capital Convention Center, and several speakers provided encouragement and professional development messages for members. Speakers included Erica Borggren, Director of the Illinois Department of Veterans Affairs and Jonathon Monken, Director of the Brandon Bodor, Executive Director of Serve Illinois, Illinois Department of Emergency Management Services. Twelve breakout administers the AmeriCorps oath at the steps of the Capitol. sessions were offered throughout the day to offer attendees a wide variety of volunteerism information. Three large service projects were also a part of the “Opening Day” of service: a Central Illinois Community Blood Center blood drive was on hand for donations, a food drive benefitting the Central Illinois Food Bank collected non-perishable food items, and the Ronald McDonald House Charities of Central Illinois hosted a pop tab collection to benefit the local Ronald McDonald House. After lunch and break-out sessions, members then began their march from the Prairie Capital Convention Center to the State Capitol Complex. The march was led by city police cars and a fire engine. Many programs marched with banners displaying their program name; other members carried small American flags. -

Download the Transcript

SERVICE-2019/10/10 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM NATIONAL SERVICE: REBUILDING AMERICA’S CIVIC FABRIC AN EVENT CO-HOSTED BY THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION AND SERVICE YEAR ALLIANCE Washington, D.C. Thursday, October 10, 2019 PARTICIPANTS: Welcome: JOHN R. ALLEN President The Brookings Institution Keynote Panel: ISABEL SAWHILL, Moderator Senior Fellow, Economic Studies The Brookings Institution JESSE COLVIN Chief Executive Officer Service Year Alliance JOE HECK Chairman of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service Former U.S. Representative (R-NV) THE HONORABLE DEVAL PATRICK Former Governor State of Massachusetts BARBARA STEWART Chief Executive Officer Corporation for National and Community Service Panel: Why We Need National Service: WILLIAM GALSTON, Moderator Ezra K. Zilkha Chair and Senior Fellow, Governance Studies The Brookings Institution ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 SERVICE-2019/10/10 2 TAIMARIE ADAMS Director, Government Relations Service Year Alliance JOHN BRIDGELAND Former Director, White House Domestic Policy Council Under President George W. Bush Vice Chair, Service Year Alliance JOHN J. DILULIO, JR. Frederic Fox Leadership Professor of Politics, Religion, and Civil Society University of Pennsylvania PETER WEHNER American Writer Senior Fellow, Ethics and Public Policy Center Panel: National Service in Practice: ALAN KHAZEI, Moderator Co-Fonder, City Year Vice Chair, Service Year Alliance WILLIAM GARTNAN AmeriCorps -

Corporation for National and Community Service Minutes of the Board of Directors Meeting September 29, 2014 4:00 P.M

Corporation for National and Community Service Minutes of the Board of Directors Meeting September 29, 2014 4:00 p.m. – 4:50 p.m., ET The CNCS Board of Directors convened in Washington, D.C. The following members of the board were present: Lisa Garcia Quiroz, Chair Hyepin Im Matthew McCabe Phyllis Segal Chair’s Opening Remarks Board chair Lisa Garcia Quiroz called the meeting to order and thanked everyone for attending. Ms. Quiroz invited members of the public who joined the meeting to comment on the business of the board. Anyone wishing to address the board should sign up so that the board may accommodate those wishing to present. Consideration of Prior Meeting’s Minutes The board considered and approved by unanimous voice vote the minutes for the public board meeting held July 31, 2014. Ms. Quiroz then spoke about the incredible momentum that is being seen around the country for national service. The momentum was for both CNCS and for the national service movement more broadly. Ms. Quiroz noted that since being charged by President Obama to be the lead agency on the President’s task force on expanding national service, CNCS has worked with partners at every level of government and with some to the nation’s great corporations to launch new programs that are bringing diverse multi-generational coalitions of Americans together in service to our communities and to the nation. Ms. Quiroz also recognized that CNCS had celebrated the 20th anniversary of AmeriCorps on September 12, 2014 and was able to highlight all of the work being done and to tell the story of national service. -

Registered Charities

RegNo CompName FullName CharityAddr City State Zip RptStatus Report Status: G=good standing; X= not in good standing; S=filing requirement is suspended 32466 #IGiveCatholic 1000 Howard Avenue, Suite 800 New Orleans LA 70113 G 32030 #WalkAway Foundation 1872 Lexington Avenue, Suite 242 New York NY 10035 G 30500 1% for the Planet, Inc. 47 Maple Street, Suite 111 Burlington VT 05401 G 32133 10,000 Entrepreneurs, Inc. C/O 1959 Palomar Oaks Way, Suite 300 Carlsbad CA 92011 G 30206 10/40 Connections, Inc. 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Chattanooga TN 37415 G 19455 1269 Cafe Ministries Craig Chevalier 351 Chestnut Street Manchester NH 03101 G 16065 171 Watson Road of Dover Holding Corporation PO Box 1217 Dover NH 03821 G 10309 1833 Society 2 Concord Street Peterborough NH 03458 G 19513 1883 Black Ice Hockey Association PO Box 3653 Concord NH 03302-3653 G 30456 1st New Hampshire Light Battery Historical Association 11 Pinecrest Circle Bedford NH 03110 S 31842 2020 Vision Quest 109 East Glenwood Street Nashua NH 03060 G 30708 22Kill 13625 Neutron Road Dallas TX 75244 G 30498 22q Family Foundation, Inc. Smart Charity 11890 Sunrise Valley Drive, Suite 206 Reston VA 20191 G 32373 2nd Vote, Inc. 341 Hill Avenue Nashville TN 37210 G 31252 32 North Media, Inc. 732 Eden Way North, #509 Chesapeake VA 23320 G 33122 350 New Hampshire 1 Washington Street Suite 3123 Dover NH 03820 G 30275 350.org 20 Jay Street, Suite 732 Brooklyn NY 11201 G 18959 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 319 Vaughan Stret Portsmouth NH 03801 G 10120 4 Lil Paws Ferret Shelter Sue Kern 49 Prescott Road Brentwood NH 03833 G 33136 4.2.20 Foundation, Inc.