The Nineteenth Century Character Assassination of Benjamin Franklin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn to Lead Activity Guide

LEARN TO LEAD ACTIVITY GUIDE CIVIL AIR PATROL CADET PROGRAMS TEAM LEADERSHIP PROBLEMS MOVIE LEARNING GUIDES GROUP DISCUSSION GUIDES Preface LEARN TO LEAD ACTIVITY GUIDE Do you learn best by reading? By listening to a lecture? By watching someone at work? If you’re like most people, you prefer to learn by doing. That is the idea behind the Learn to Lead Activity Guide. Inside this guide, you will find: • Hands-on, experiential learning opportunities • Case studies, games, movies, and puzzles that test cadets’ ability to solve problems and communicate in a team environment • Recipe-like lesson plans that identify the objective of each activity, explain how to execute the activity, and outline the main teaching points • Lesson plans are easy to understand yet detailed enough for a cadet officer or NCO to lead, under senior member guidance The Activity Guide includes the following: • 24 team leadership problems — Geared to cadets in Phase I of the Cadet Program, each team leadership problem lesson plan is activity- focused and addresses one of the following themes: icebreakers, teamwork fundamentals, problem solving, communication skills, conflict resolution, or leadership styles. Each lesson plan includes step-by-step instructions on how to lead the activity, plus discussion questions for a debriefing phase in which cadets summarize the lessons learned. • 6 movie learning guides — Through an arrangement with TeachWithMovies.com, the Guide includes six movie learning guides that relate to one or more leadership traits of Learn to Lead: character, core values, communication skills, or problem solving. Each guide includes discussion questions for a debriefing phase in which cadets summarize the lessons learned. -

![Benjamin Franklin Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8385/benjamin-franklin-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-28385.webp)

Benjamin Franklin Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Benjamin Franklin Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2000 Revised 2018 January Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003048 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm73021451 Prepared by Division Staff Revised and expanded by Donna Ellis Collection Summary Title: Benjamin Franklin Papers Span Dates: 1726-1907 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1770-1789) ID No.: MSS21451 Creator: Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790 Extent: 8,000 items ; 40 containers ; 12 linear feet ; 12 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Statesman, publisher, scientist, and diplomat. Correspondence, journals, records, articles, and other material relating to Franklin's life and career. Includes manuscripts (1728) of his Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion; negotiations in London (1775); letterbooks (1779-1782) of the United States legation in Paris; records (1780-1783) of the United States peace commissioners, including journals kept by Franklin and Richard Oswald; and papers (1781-1818) of Franklin's grandson, William Temple Franklin (1760-1823). Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Adams, John, 1735-1826--Correspondence. Bache, Richard, 1737-1811--Correspondence. Carmichael, William, -1795--Correspondence. Cushing, Thomas, 1725-1788--Correspondence. Dumas, Charles Guillaume Frédéric, 1721-1796--Correspondence. -

A Parent and Teen's Guide to Avoiding Dating Violence

Dating Violence Myths For More Information: • It does not affect many people or only oc- The Julian Center curs among those who hang out in bars, www.juliancenter.org are poor, or are people of color Breaking Free, Inc. • It does not occur in gay and lesbian rela- www.skynet.net/~break/ tionships Coburn Place Safe Haven • Men are never victims www.coburnplace.org Domestic Violence Center • Victims are free to leave at any time www.dvnconnect.org • Victims are mentally ill Indiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence • This type of violence is only a momentary 800-538-3393 www.icadvinc.org loss of temper 211 Connect2Help Resource Line Facts References • 1 of 3 high school relationships involve abuse; 1 of 5 include sexual/physical Crompton, V. (2003), Saving Beauty from the Beast (1st abuse ed.). Boston, MA: Little & Brown • Aggression typically escalates over time Frisch, L., & Frisch, N. (2006) Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing (3rd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Cengage Learn- • Abuse is more likely in close relationships ing. Lowen, L (2009). 10 Facts About Teen Violence-Teen Da- • Pregnancy will typically increase abuse ting Abuse Facts. Retrieved from www.womensissues. about.com/od/datingandsex/a/TeenDatingAbuse.htm • Verbal and emotional abuse can be just as damaging as physical or sexual abuse Sperekas, N. (2005). But he says he loves me: girls speak out on dating abuse. Brandon, CT: Safer Society Press • The longer the relationship, the harder it is to leave A Parent and Teen’s • Dating violence occurs every 15 minutes • Most rapists -

American Pioneer Prose Writers

American Pioneer Prose Writers By Hamilton Wright Mabie JONATHAN EDWARDS Jonathan Edwards was one of the most impressive figures of his time. He was a deep thinker, a strong writer, a powerful theologian, and a constructive philosopher. He was born on October 5, 1703, at East (now South) Windsor, Connecticut. His father, Timothy Edwards, was a minister of East Windsor, and also a tutor. Jonathan, the only son, was the fifth of eleven children. Even as a boy he was thoughtful and serious minded. It is recorded that he never played the games, or got mixed up in the mischief that the usual boy indulges in. When he was only ten years old he wrote a tract on the soul. Two years later he wrote a really remarkable essay on the “Flying Spider.” He entered Yale and graduated at the head of his class as valedictorian. The next two years he spent in New Haven studying theology. In February, 1727, he was ordained minister at Northampton, Massachusetts. In the same year he married Sarah Pierrepont, who was an admirable wife and became the mother of his twelve children. In 1733 a great revival in religion began in Northampton. So intense did this become in that winter that the business of the town was threatened. In six months nearly 300 were admitted to the church. Of course Edwards was a leading spirit in this revival. The orthodox leaders of the church had no sympathy with it. At last a crisis came in Edwards’ relations with his congregation, which finally ended in his being driven from the church. -

Anti Bullying Policy V1: 2020

ANTIACADEMIC-BULLYING POLICY This policy will be kept up to date and will be reviewed once per year as part of the company’s Quality Assurance arrangements. Review Period Approved by Review Carried Out By Date of Approval 1 Year Directors/Governors Quality Team November 2020 Introduction At Orion all staff have a duty to provide a safe and secure environment for all. Orion should be free from violence, should encourage a caring and respectful environment and should be physically and psychologically healthy. We must all strive to uphold this healthy environment. At Orion we believe that all forms of bullying are unacceptable and should not be tolerated. We want all students to be and feel safe from bullying and all forms of discrimination. We want everyone who works with students to take bullying seriously and know how to resolve it positively. As bullying happens at all levels of society we seek to empower our students to challenge, remedy and prevent bullying, creating a culture where every person is treated with dignity and respect and takes seriously their responsibility to treat others in the same way. There is no legal definition of bullying but Orion adopts the ‘Dfe’s definition of bullying: “Bullying is behaviour by an individual or group repeated over time that intentionally hurts another individual or group either physically or emotionally.” Bullying Behaviour Bullying can take many forms, including: • Verbal name calling, insults, jokes, offensive language or comments, including graffiti, threats, innuendo, teasing, taunting, bragging, ridicule • Physical unprovoked assaults such as prodding, pushing, hitting or kicking, ‘rushing’, shaking, inappropriate touching, blocking the way, capturing, contact involving objects used as weapons • Social humiliation through exclusion or rejection by peer group, ‘blanking’, spreading rumours, gossiping, peer pressure to conform, using difference as a dividing factor, control or power over a relationship • Cyber-bullying via the internet, email or mobile phone, e.g. -

A Service Year a Cultural Expectation, a Common Opportunity, and a Civic Rite of Passage for Every Young American

A SERVICE YEAR A CULTURAL EXPECTATION, A COMMON OPPORTUNITY, AND A CIVIC RITE OF PASSAGE FOR EVERY YOUNG AMERICAN THE VISION The Franklin Project envisions a future in which a year of full-time national service — a service year — is a cultural expectation, a common opportunity, and a civic rite of passage for every young American. Each person can fulfill his or her national service obligation by joining the military or by completing a full-time civilian service year through programs such as Teach for America, AmeriCorps, and the Peace Corps, or any eligible nonprofit. A modest living allowance would be provided for the service year, which would be completed at some point between the ages of 18-28. THEORY OF THE FRANKLIN PROJECT We believe that spending a year in full-time service is a transformative experience for young citizens and future leaders. We’re focused on promoting a service year as a civic rite of passage because it will connect individuals to something bigger than themselves and to the idea that citizenship requires more from each of us than is currently expected. A generation of Americans spending a year in full-time service will unleash a reservoir of human capital to tackle pressing social challenges, unite diverse Americans in common purpose, and cultivate the next generation of leaders. HOW IT WILL WORK: A NEW RITE OF PASSAGE INTO ADULTHOOD RECRUIT SERVE CONNECT ATTRACTRECRUIT YOUNG PEOPLE TO THE PLACE 18- TO 28- YEAR-OLDS INTO ATTACH FULL-TIME SERVICE TO SERVICE YEAR EXPERIENCE SERVICE YEAR POSITIONS EMPLOYMENT AND EDUCATION CONTEXT In 2011, AmeriCorps CONTEXT Nonprofits and federal, CONTEXT Service years are an asset had 580,000 applications for 80,000 state, and local governments to career and adult development, positions, and studies show recognize national service as a rather than an interruption — and that millennials are increasingly cost-effective solution to meet their service year alumni make better inclined to serve, volunteering at missions, and colleges have already employees and more mature students. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Steve, Attached You Will Find an Agenda for the 3

Steve, Attached you will find an agenda for the 3 day leadership training I received as part of the Aspen Institute/Franklin Project Ambassador/Fellowship. I was recently selected as an Ambassador/Fellow. The fellowship is an unpaid year-long fellowship supported by the Aspen Institute to promote National service which includes service in the Military and Public Service. 50 Ambassadors/Fellows were chosen from across the United States and all Ambassadors were at the 3 day training. I previously served in two Americorps programs; City Year and Public Allies. The Franklin Project envisions a future in which a year of full-time national service is a cultural expectation, a common opportunity, and a civic rite of passage for every young American. The Aspen Institute/Franklin Project Aspen Institute (Ambassadors) is leading the effort to improve citizenship by giving every young person in America the opportunity to serve. Sometime between the ages of 18 and 28, the young person would do a fully paid, full-time year of service in one of an array of areas, including health, poverty, conservation, or education. These young people will not only do good work and solve problems, but they will also become better young Americans. Let me know if you have any questions. Mark Payne Franklin Project Ambassadors Program Training and Seminar Agenda June 22-24, 2015 Alexandria, VA Monday 22 June 2015 12:30 – 1:00 pm Arrival Participants arrive at McChrystal Group Headquarters. Snacks and mingling. 1:00 – 1:15 pm Kickoff Welcome, objectives of the training, agenda review, logistics review. -

Heroic Individualism: the Hero As Author in Democratic Culture Alan I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture Alan I. Baily Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baily, Alan I., "Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1073. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1073 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HEROIC INDIVIDUALISM: THE HERO AS AUTHOR IN DEMOCRATIC CULTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Alan I. Baily B.S., Texas A&M University—Commerce, 1999 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 December, 2006 It has been well said that the highest aim in education is analogous to the highest aim in mathematics, namely, to obtain not results but powers , not particular solutions but the means by which endless solutions may be wrought. He is the most effective educator who aims less at perfecting specific acquirements that at producing that mental condition which renders acquirements easy, and leads to their useful application; who does not seek to make his pupils moral by enjoining particular courses of action, but by bringing into activity the feelings and sympathies that must issue in noble action. -

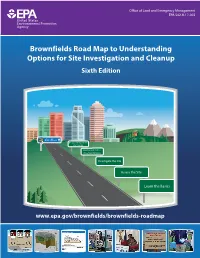

Epa 542-R-17-003

Oce of Land and Emergency Management EPA 542-R-17-003 Brownf ields Road Map to Understanding Options for Site Investigation and Cleanup Sixth Edition Site Reuse Design and Implement the Cleanup Assess and Select Cleanup Options Investigate the Site Assess the Site Learn the Basics www.epa.gov/brownfields/brownfields-roadmap [This page is intentonally left blank] Table of Contents Brownfields Road Map Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Follow the Brownfields Road Map ...................................................................................... 6 Learn the Basics .................................................................................................................. 9 Assess the Site ................................................................................................................... 20 Investigate the Site ........................................................................................................... 26 Assess and Select Cleanup Options ................................................................................... 36 Design and Implement the Cleanup ................................................................................. 43 Spotlights 1 Innovations in Contracting ................................................................................... 18 2 Supporting Tribal Revitalization ........................................................................... 19 -

Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 1 - - 2 - Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea The Representation of Black Heroism in American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 4 - Table of Contents: Preface Chapter One: The Western Victimization of African Americans during and after Slavery 1.1 – Visual Culture in Propaganda 1.2 - African Americans as Victims of the System of Slavery 1.3 - The Gift of Freedom 1.4 - The Influence of White Stereotypes on the Perception of Blacks 1.5 - Racial Discrimination in Criminal Justice 1.6 - Conclusion Chapter Two: Black Heroism in Modern American Cinema 2.1 – Representing Racial Agency Through Passive Characters 2.2 - Django Unchained: The Frontier Hero in Black Cinema 2.3 - Character Development in Django Unchained 2.4 - The White Savior Narrative in Hollywood's Cinema 2.5 - The Depiction of Black Agency in Hollywood's Cinema 2.6 - Conclusion Chapter Three: The Different Interpretations -

Benjamin Franklin People Mentioned in Walden

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN BENJAMIN “VERSE-MAKERS WERE GENERALLY BEGGARS” FRANKLIN1 Son of so-and-so and so-and-so, this so-and-so helped us to gain our independence, instructed us in economy, and drew down lightning from the clouds. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Franklin was distantly related to Friend Lucretia Mott, as was John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Adams, and Octavius Brooks Frothingham. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF WALDEN: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN WALDEN: In most books, the I, or first person, is omitted; in this PEOPLE OF it will be retained; that, in respect to egotism, is the main WALDEN difference. We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking. I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well. Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN WALDEN: But all this is very selfish, I have heard some of my PEOPLE OF townsmen say. I confess that I have hitherto indulged very little WALDEN in philanthropic enterprises. I have made some sacrifices to a sense of duty, and among others have sacrificed this pleasure also. There are those who have used all their arts to persuade me to undertake the support of some poor family in town; and if I had nothing to do, –for the devil finds employment for the idle,– I might try my hand at some such pastime as that.