St. Anna Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bekanntgabe Der Maßnahmen Zur Bekämpfung Der Amerikanischen Rebzikade Für Das Jahr 2020 in Den Weinbaugebieten Vulkanland Steiermark, Südsteiermark Und Weststeiermark

Bekanntgabe der Maßnahmen zur Bekämpfung der Amerikanischen Rebzikade für das Jahr 2020 in den Weinbaugebieten Vulkanland Steiermark, Südsteiermark und Weststeiermark gemäß SS 5 (2) und 9 (2) der Verordnung zur Bekämpfung der Amerikanischen Rebzikade und der Goldgelben Vergilbung der Rebe, LGB|.Nr. 3512010 idF LGB|.Nr.3212020 Amerikanische Rebzikade Die Amerikanische Rebzikade (ARZ), Überträger der gefährlichen Phytoplasmose ,,Grapevine flavescence dor6e" (GFD, Goldgelbe Vergilbung der Rebe), wurde 2004 erstmals im Raum Klöch und St. Anna am Aigen gefunden. ln den ersten Jahren wurden nur enrvachsene Zikaden (Adulte) beobachtet, zwischenzeitig ist die ARZ in großen Teilen der Weinbaugebiete Vulkan- land Steiermark und Südsteiermark und im Süden der Weststeiermark heimisch geworden, d.h. sie übenruintert als Ei und durchlebt alle fünf Larvenstadien bis zur adulten Zikade. Der österreichweit erste Ausbruch von Grapevine flavescence doröe wurde im Herbst 2009 in der Gemeinde Tieschen festgestellt. lm Jahr 2019 wurden an drei Standorten einzelne Rebstöcke positiv auf GFD getestet und diese in weiterer Folge gerodet. Lebenszyklus Die in Borkenritzen übenarinternden Eier sind immer frei von der Krankheit. Damit es zu einer Verbreitung der Goldgelben Vergilbung kommen kann, müssen entweder befallene Rebstöcke (Meldepflicht!) innerhalb eines Weinbaugebietes vorhanden sein oder infektiöse Zikaden aus anderen Gebieten im Sommer zufliegen. Daher ist es wichtig, befallene Reben so rasch wie möglich zu entfernen und die Population der ARZ durch geeignete Maßnahmen zu verringern. Der Larvenschlupf beginnt je nach Witterung Ende Mai bis Anfang Juni. Die Larven bleiben meist auf derselben Rebe und halten sich voniviegend auf den Blattunterseiten auf. Von der Aufnahme des Krankheitserregers Flavescence dor6e bis zur Fähigkeit, die Vergilbungskrank- heit weiterzugeben, vergehen ca. -

Pr\344Mierte Betriebe Nach Bezirk U. Gemeinde 2013Xls.Xls

Landesprämierung Steirisches Kürbiskernöl g.g.A 2013 Bezirk Deutschlandsberg Aibl Fürpaß Siegfried Aibl 38 8552 Aibl Bad Gams Deutsch Barbara Furth 1 8524 Bad Gams Ganster Rudolf Niedergams 31 8524 Bad Gams Mandl Manfred Niedergams 22 8524 Bad Gams Farmer-Rabensteiner Franz Furth 8 8524 Bad Gams Deutschlandsberg Hamlitsch KG Ölmühle Wirtschaftspark 28 8530 Deutschlandsberg Leopold Ölmühle Frauentalerstraße 120 8530 Deutschlandsberg Reiterer Josef Bösenbacherstraße 94 8530 Deutschlandsberg Schmuck Johann Blumauweg-Wildbach 77 8530 Deutschlandsberg Groß Sankt Florian Jauk Josef Hubert Petzelsdorfstraße 31 8522 Groß Sankt Florian Weißensteiner Gabriele Vocherastraße 27 8522 Groß Sankt Florian Otter Anton Gussendorfgasse 21 8522 Groß Sankt Florian Schmitt Jakob Kelzen 14 8522 Groß Sankt Florian Stelzer Gertrude Florianerstraße 61 8522 Groß Sankt Florian Lamprecht Stefan Kraubathstraße 34 8522 Groß Sankt Florian Großradl Wechtitsch Angelika Oberlatein 32 8552 Großradl Lannach Jöbstl Karl Hauptstraße 7 8502 Lannach Niggas Theresia Radlpaßstraße 13 8502 Lannach Rumpf Herta Kaiserweg 4 8502 Lannach Limberg bei Wies Gollien Josef Eichegg 62 8542 Limberg bei Wies Pitschgau Jauk Karl Heinz Bischofegg 14 8455 Pitschgau Kürbisch Anna Bischofegg 20 8455 Pitschgau Kainacher Inge Haselbach 8 8552 Pitschgau Stampfl Gudrun Hörmsdorf 23 8552 Pitschgau Pölfing-Brunn Jauk Christian Brunn 45 8544 Pölfing-Brunn Michelitsch Karl Pölfing 29 8544 Pölfing-Brunn Preding Bauer Erwin Wieselsdorf 38 8504 Preding Rassach Hirt Renate Herbersdorf 35 8510 Rassach Becwar -

Landesprämierung Steirisches Kürbiskernöl G.G.A. 2018

Landesprämierung Steirisches Kürbiskernöl g.g.A. 2018 Bad Gleichenberg Hackl Barbara Merkendorf 70 8344 Bad Gleichenberg Bad Radkersburg Drexler Manfred Neudörflweg 5 8490 Bad Radkersburg Friedl Jasmin Pridahof 12 8490 Bad Radkersburg Majczan Josef Sicheldorf 38 8490 Bad Radkersburg Deutsch Goritz Baumgartner Irene - Agnes Weixelbaum 15 8484 Unterpurkla Lackner Andreas Weixelbaum 14 8483 Deutsch Goritz Edelsbach bei Feldbach Wiedner-Hiebaum Herbert Rohr 7 8332 Edelsbach b. Feldbach Fehring Bauer Franz Schiefer 119 8350 Fehring Dirnbauer Friedrich Höflach 22a 8350 Fehring Esterl Josef Schiefer 86 8350 Fehring Gütl Alfred Hatzendorf 65 8361 Hatzendorf Kaufmann Ernst u. Elisabeth Höflach 16 8350 Fehring Kern Stefanie Schiefer 13 8350 Fehring Kniely jun. Johann Pertlstein 31 8350 Fehring Koller jun. Josef Schiefer 29 8350 Fehring Krenn Josef u. Elisabeth Hohenbrugg 33 8350 Fehring Kürbishof Koller Weinberg 78 8350 Fehring Lamprecht Günter Weinberg 26 8350 Fehring Reindl Franz Höflach 45 8350 Fehring Schnepf Peter August Petzelsdorf 5 8350 Fehring Zach Johannes Pertlstein 29 8350 Fehring Feldbach Fritz Clement KG Brückenkopfgasse 11 8330 Feldbach Groß Franz Unterweißenbach 51 8330 Feldbach Holler Josef Petersdorf 3 8330 Feldbach Kirchengast Maria Mühldorf 62 8330 Feldbach Kohl David Leitersdorf 8 8330 Feldbach Lugitsch Rudolf KG Gniebing 122 8330 Feldbach Neuherz Christian Edersgraben 2 8330 Feldbach Gnas Ettl Hannes u. Maria Raning 44 8342 Gnas Fruhwirth Johann u. Johanna Thien 33 8342 Gnas Hödl Josef Raning 92 8342 Gnas Kerngast Anita Burgfried 65/1 8342 Gnas Neubauer Alois Obergnas 27 8342 Gnas Niederl Günter Obergnas 12 8342 Gnas Reiss Manfred u. Doris Grabersdorf 71 8342 Gnas Schadler Elisabeth Hirsdorf 23 8342 Gnas Sommer Alois Lichtenberg 84 8342 Gnas Trummer Josef Katzendorf 6 8342 Gnas Wagner Johannes Lichtenberg 12 8342 Gnas Halbenrain Gangl Christoph Donnersdorf 38 8484 Unterpurkla Summer Michaela Dietzen 32 8492 Halbenrain Jagerberg Fastl Justine Pöllau 6 8091 Jagerberg Groß Erwin Wetzelsdorf 17 8083 St. -

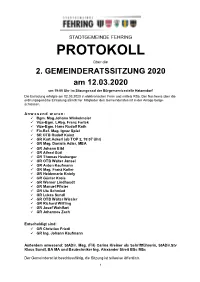

Protokoll 2. Gemeinderatssitzung 2020

STADTGEMEINDE FEHRING PROTOKOLL über die 2. GEMEINDERATSSITZUNG 2020 am 12.03.2020 um 19:00 Uhr im Sitzungssaal der Bürgerservicestelle Hatzendorf Die Einladung erfolgte am 02.03.2020 in elektronischer Form und mittels RSb. Der Nachweis über die ordnungsgemäße Einladung sämtlicher Mitglieder des Gemeinderates ist in der Anlage beige- schlossen. Anwesend waren: ü Bgm. Mag.Johann Winkelmaier ü Vize-Bgm. LAbg. Franz Fartek ü Vize-Bgm. Hans Rudolf Rath ü Fin.Ref. Mag. Ignaz Spiel ü SR OTB Rudolf Kainz ü GR Kurt Ackerl (ab TOP 2, 19:07 Uhr) ü GR Mag. Daniela Adler, MBA ü GR Johann Eibl ü GR Alfred Gütl ü GR Thomas Heuberger ü GR OTB Walter Jansel ü GR Anton Kaufmann ü GR Mag. Franz Koller ü GR Heidemarie Kniely ü GR Günter Krois ü GR Werner Lindhoudt ü GR Manuel Pfister ü GR Ute Schmied ü GR Lukas Sundl ü GR OTB Walter Wiesler ü GR Richard Wilfling ü GR Josef Wohlfart ü GR Johannes Zach Entschuldigt sind: ü GR Christian Friedl ü GR Ing. Johann Kaufmann Außerdem anwesend: StADir. Mag. (FH) Carina Kreiner als Schriftführerin, StADir.Stv Klaus Sundl, BA MA und Bautechniker Ing. Alexander Streit BSc MSc Der Gemeinderat ist beschlussfähig, die Sitzung ist teilweise öffentlich. 1 Vorsitzender: Bgm. Mag. Johann Winkelmaier TAGESORDNUNG: Öffentlicher Teil: 1 Eröffnung, Begrüßung und Feststellung der Beschlussfähigkeit 2 Fragestunde 3 Sitzungsprotokoll der 01. Sitzung 2020 des Gemeinderates 4 Beratung und Beschlussfassung – Dislozierter Standort der Musikschule Fehring in Kirchberg an der Raab 5 Bericht des Prüfungsausschusses über die Prüfung 4. Quartal 2019 6 Bericht des Prüfungsausschusses über die Überprüfung des Rechnungsabschlusses 2019 7 Beratung und Beschlussfassung – Rechnungsabschluss 2019 8 Beratung und Beschlussfassung – Vergabe Aufträge Kasernenbrunnen 9 Beratung und Beschlussfassung – Vorhaben Haus der Musik Fehring - Auftragsvergaben 10 Beratung und Beschlussfassung – Verkauf Grdstk. -

PDF-Dokument

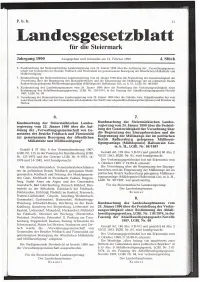

P. b. b. 2L Lamdesgesetzb'Eatt für die Steierrnark Jahrgang 1990 Ausgegeben und versendet am 14. Februar 1990 4. Stück Kundmachung der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung vom 25. Jänner'1990 über die Auflösung der ,,Verwaltungsgemein- schaft von Gemeinden der Bezirke Feldbach und Fürstenfeld zur gemeinsamen Besorgung der öffentlichen MüIlabfuhr und Müllbeseitigung ". 7, Kundmachung der Steiermäikischen Landesregierung vom 24. Jänner 1990 über die Feststeliung der Gesetzwidrigkeit der Verordnung über die Begrenzung des Einzugsbereiches und die Eingrenzung der Müllmenge der im politischen Bezirk Radkersburg gelegenen Müllbeseitigungsanlage (Mülldeponie) Halbenrain Ges. m. b, H., LGBI. Nr. 9Bi 1987. Kundmachung des Landeshauptmannes vom 24. Jänner 1990 über die Feststellung der Verfassungswidrigkeit einer Bestimmung des Abfallbeseitigungsgesetzes, LGBI. Nr. 118/1974, in der Fassung der Abfallbeseitigungsgesetz-Novelle 1987, LGBL NT. 68. 9. Verordnung der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung vom 22. Jänner 1990 über die Gehalts- bzw. Entgeltsansätze der vom Land Steiermark oder von den Gemeinden mit Ausnahme der Stadt Graz angestellten Ki4dergärtner(innen) und Erzieher an Horten. 6. 7. Kundmachung der Steiermärkischen Landes- Kundmachung der Steiermärkischen Landes- regierung vom 25. Jänner 1990 über die Auf- regierung vom 24. Jänner 1990 über die Feststel- lösung der ,Verwaltungsgemeinschaft von Ge- lung der Gesetzwidrigkeit der Verordnung über meinden der Bezirke Feldbach und Fürstenield die Begrenzung des Einzugsbereiches und die zur gemeinsamen Besorgung der öifentlichen Eingrenzung der Mültmenge der im politischen Müllabiuhr und Müllbeseitigung" Bezirk Radkersburg gelegenen Müllbesei- tigungsanlage (Mülldeponie) Halbenrain Ges. m. b. H., LGBI. Nr. 98/1987 Gemäß $ 37 Abs. 6 der Gemeindeordnung 1967, LGBI. Nr. 115, in der Fassung der Kundmachung LGBI. Gemäß Art. 139 Abs, 5 B-VG und gemäß 0 60 Abs, 2 Nr. -

Empfohlene Bekämpfungsmaßnahmen

Bezirkskammer für Land- und Forstwirtschaft Leibnitz Referat: Pflanzenschutz Titel: Weinbau – Warnmeldung Nr. 5/19 Leibnitz, 26. Juni 2019 AMERIKANISCHE REBZIKADE: Erste Larven des dritten Larvenstadiums wurden in der letzten Woche (25. Kalenderwoche) im Zuge der Monitoringmaßnahmen des Landes Steiermark gefunden. Die Larven können ab diesem Stadium die Quarantänekrankheit Grapevine flavescence dorée (GFD, Goldgelbe Vergilbung) übertragen! Wegen der für Zikaden ungünstigen Wettersituation in der letzten Woche sind allerdings die Fangzahlen in den Weingärten im Vergleich zu den Vorwochen etwas zurückgegangen. Von verpflichtenden Maßnahmen zur Larvenbekämpfung wird daher vorerst abgesehen. Es wird aber dringend empfohlen, im Verbreitungsgebiet der Amerikanischen Rebzikade Maßnahmen gegen die Larven zu beginnen bzw. fortzuführen. Verbreitungsgebiet: Das Verbreitungsgebiet der ARZ umfasst folgende Gemeinden in den jeweiligen Bezirken: Bezirk Deutschlandsberg: Gemeinden Eibiswald, Pölfing-Brunn, St. Martin im Sulmtal und Wies Bezirk Hartberg-Fürstenfeld: Gemeinden Bad Blumau, Bad Waltersdorf, Buch-Sankt Magdalena, Ebersdorf, Fürstenfeld, Großwilfersdorf, Ilz, Loipersdorf bei Fürstenfeld, Ottendorf an der Rittschein und Söchau Bezirk Leibnitz: Gemeinden Arnfels, Ehrenhausen an der Weinstraße, Gamlitz, Gleinstätten, Großklein, Heimschuh, Kitzeck im Sausal, Leibnitz, Leutschach an der Weinstraße, Oberhaag, Sankt Andrä-Höch, Sankt Johann im Saggautal, Sankt Nikolai im Sausal, Sankt Veit in der Südsteiermark, Straß-Spielfeld, Tillmitsch und Wagna -

Gesetz Vom 25

1 von 2 En twur f II Abteilung 10/Stand: 12.11.2014 elektronischen Signatur bzw. der Echtheit de Das elektronische Original dieses Dokumentes wurde amtssigniert. Hinweise zur Prüfung dieser Verordnung der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung vom , mit der die Verordnung über die Bekämpfung der Amerikanischen Rebzikade und der Goldgelben Vergilbung der Rebe geändert wird Auf Grund des § 4 Abs. 1 des Steiermärkischen Pflanzenschutzgesetzes, LGBl. Nr. 82/2002, zuletzt in der Fassung LGBl. Nr. 185/2013, wird verordnet: Die Verordnung über die Bekämpfung der Amerikanischen Rebzikade und der Goldgelben Vergilbung der Rebe, LGBl. Nr. 35/2010, Novelle LGBl. Nr. 39/2011, Novelle LGBl. Nr. 31/2012, zuletzt in der Fassung LGBl. Nr. 37/2013 wird wie folgt geändert: s Ausdrucks finden Sie unter: 1. § 4 Abs. 2 lautet: „(2) Das Verbreitungsgebiet der ARZ umfasst folgende Gemeinden: Bezirk Deutschlandsberg: die Gemeinden Eibiswald, Pölfing-Brunn, Sankt Martin im Sulmtal und Wies. Bezirk Hartberg-Fürstenfeld: die Gemeinden Bad Blumau, Bad Waltersdorf, Buch-Sankt Magdalena, Ebersdorf, Fürstenfeld, Großwilfersdorf, Loipersdorf bei Fürstenfeld und Söchau. Bezirk Leibnitz: die Gemeinden Arnfels, Ehrenhausen an der Weinstraße, Gamlitz, Gleinstätten, https://as.stmk.gv.at Großklein, Heimschuh, Kitzeck im Sausal, Leibnitz, Leutschach an der Weinstraße, Oberhaag, Sankt Andrä-Höch, Sankt Johann im Saggautal, Sankt Nikolai im Sausal, Sankt Veit in der Südsteiermark, Straß-Spielfeld, Tillmitsch und Wagna. Bezirk Südoststeiermark: die Gemeinden Bad Gleichenberg, Bad Radkersburg, Deutsch Goritz, Fehring, Feldbach, Gnas, Halbenrain, Jagerberg, Kapfenstein, Klöch, Mettersdorf am Saßbach, Mureck, Murfeld, Riegersburg, Sankt Peter am Ottersbach, Sankt Anna am Aigen, Straden, Tieschen und Unterlamm.“ 2. § 8 Abs. 8 lautet: „(8) Die Pläne werden durch Auflage zur öffentlichen Einsichtnahme kundgemacht. -

Bgbl II 243/2012

1 von 4 BUNDESGESETZBLATT FÜR DIE REPUBLIK ÖSTERREICH Jahrgang 2012 Ausgegeben am 4. Juli 2012 Teil II 243. Verordnung: Bezirksgerichte-Verordnung Steiermark 2012 243. Verordnung der Bundesregierung über die Zusammenlegung von Bezirksgerichten und über die Sprengel der verbleibenden Bezirksgerichte in der Steiermark (Bezirksgerichte-Verordnung Steiermark 2012) Auf Grund des § 8 Abs. 5 lit. d des Übergangsgesetzes vom 1. Oktober 1920, BGBl. Nr. 368/1925, in der Fassung des Bundesverfassungsgesetzes BGBl. I Nr. 64/1997 und der Kundmachung BGBl. I Nr. 194/1999 wird mit Zustimmung der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung verordnet: Zusammenlegung von Bezirksgerichten § 1. Folgende in der Steiermark gelegene Bezirksgerichte werden zusammengelegt: Aufnehmende Bezirksgerichte 1. Bad Radkersburg Feldbach 2. Frohnleiten Graz-West 3. Gleisdorf Weiz 4. Hartberg Fürstenfeld 5. Irdning Liezen 6. Knittelfeld Judenburg 7. Stainz Deutschlandsberg Sprengel der Bezirksgerichte § 2. In der Steiermark bestehen folgende Bezirksgerichte, deren Sprengel nachgenannte Gemeinden umfassen: Bezirksgericht Gemeinden 1. Bruck an der Mur Aflenz Kurort, Aflenz Land, Breitenau am Hochlantsch, Bruck an der Mur, Etmißl, Frauenberg, Gußwerk, Halltal, Kapfenberg, Mariazell, Oberaich, Parschlug, Pernegg an der Mur, Sankt Lorenzen im Mürztal, Sankt Ilgen, Sankt Katharein an der Laming, Sankt Marein im Mürztal, Sankt Sebastian, Thörl, Tragöß, Turnau. 2. Deutschlandsberg Aibl, Bad Gams, Deutschlandsberg, Eibiswald, Frauental an der Laßnitz, Freiland bei Deutschlandsberg, Garanas, Georgsberg, Greisdorf, Gressenberg, Groß Sankt Florian, Großradl, Gundersdorf, Hollenegg, Kloster, Lannach, Limberg bei Wies, Marhof, Osterwitz, Pitschgau, Pölfing-Brunn, Preding, Rassach, Sankt Josef (Weststeiermark), Sankt Martin im Sulmtal, Sankt Oswald ob Eibiswald, Sankt Peter im Sulmtal, Sankt Stefan ob Stainz, Schwanberg, Soboth, Stainz, Stainztal, Stallhof, Sulmeck-Greith, Trahütten, Unterbergla, Wernersdorf, Wettmannstätten, Wielfresen, Wies. 3. -

AMT DER STEIERMÄRKISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Land- Und Forstwirtschaft Abteilung 10

AMT DER STEIERMÄRKISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Land- und Forstwirtschaft Abteilung 10 Bearbeiter/in: Mag. Freydis Ergeht an: Burgstaller-Gradenegger, MBA Tel.: +43 (316) 877-6609 Fax: +43 (316) 877-6900 siehe Verteiler E-Mail: [email protected] Hinweise zur Prüfung finden Sie unter https://as.stmk.gv.at. Das elektronische Original dieses Dokumentes wurde amtssigniert. Bei Antwortschreiben bitte Geschäftszeichen (GZ) anführen __ GZ: ABT10-57726/2014-65 Graz, am 04.02.2021 Ggst.: Entwurf einer Verordnung der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung, mit der die Verordnung über die Bekämpfung der Amerikanischen Rebzikade und der Goldgelben Vergilbung der Rebe geändert wird; Begutachtung Das Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung übermittelt den beiliegenden Verordnungsentwurf zur allfälligen Stellungnahme bis 18. Februar 2021. Sollte bis dahin eine Stellungnahme nicht eingelangt sein, wird angenommen, dass keine Bedenken dagegen bestehen. Bitte übermitteln Sie Ihre Stellungnahme per E-Mail an [email protected] und verwenden Sie in der Betreffzeile das Wort „Begutachtung“. Nach § 2 Volksrechtegesetz hat jede Person das Recht, im Begutachtungsverfahren eine schriftliche Stellungnahme abzugeben. Diese Stellungnahmen sind zu veröffentlichen. Sie finden den Entwurf und dazu abgegebene Stellungnahmen unter www.landesrecht.steiermark.at. Für die Steiermärkische Landesregierung Der Abteilungsleiter Mag. Franz Grießer (elektronisch gefertigt) Beilagen 8047 Graz Ragnitzstraße 193 https://datenschutz.stmk.gv.at ● UID ATU37001007 ● Landes-Hypothekenbank Steiermark: IBAN AT375600020141005201 ● BIC HYSTAT2G LegHB_VorA9_V2.2_02/2015 - 2 - Ergeht an: 1. Landesamtsdirektion - Ressortübergreifende Wirkungscontrollingstelle, Hofgasse 15, 8010 Graz, per E-Mail 2. Gemeindebund Steiermark, Stadionplatz 2/7, 8041 Graz, per E-Mail 3. Österreichischer Städtebund - Landesgruppe Steiermark, Sackstraße 20, 8010 Graz, per E- Mail 4. Postfach Begutachtung, per E-Mail 5. Bundesministerium für Landwirtschaft, Regionen und Tourismus, Stubenring 1, 1010 Wien, per E-Mail 6. -

Waldbrandverordnung 2021

BEZIRKSHAUPTMANNSCHAFT SÜDOSTSTEIERMARK Anlagenreferat Bezirkshauptmannschaft Südoststeiermark Bearb.: Ing.Mag. Alois Maier Tel.: +43 (3152) 2511-213 Fax: +43 (3152) 2511-550 E-Mail: bhso- [email protected] Bei Antwortschreiben bitte elektronischen Signatur bzw. der Echtheit de Das elektronische Original dieses Dokumentes wurde amtssigniert. Hinweise zur Prüfung dieser Geschäftszeichen (GZ) anführen __ GZ: BHSO-62028/2021-3 Feldbach, am 29.03.2021 Ggst.: Waldbrandverordnung 2021 V E R O R D N U N G über das Verbot von Feuerentzünden und Rauchen im Wald s Ausdrucks finden Sie unter: in Zeiten besonderer Brandgefahr Aufgrund des § 41 Abs. 1 Forstgesetz 1975, BGBl. Nr. 440 idgF wird verordnet: § 1 Zur Hintanhaltung von Waldbränden sind in allen Waldgebieten des Verwaltungsbezirkes Südoststeiermark und in deren Gefährdungsbereich (40 m zu Wäldern) brandgefährliche https://as.stmk.gv.at Handlungen wie das Rauchen, das Hantieren mit offenem Feuer, die Verwendung von pyrotechnischen Gegenständen, jegliches Feuerentzünden und das Unterhalten von Feuer für jedermann, einschließlich der im § 40 Abs. 2 Forstgesetz 1975 zum Entzünden oder Unterhalten von Feuer im Walde Befugten, verboten! § 2 Diese Verordnung tritt mit dem der Kundmachung folgenden Tag in Kraft. § 3 Zuwiderhandlungen gegen dieses Verbot stellen Verwaltungsübertretungen nach § 174 Abs. 1 a Ziffer 17 Forstgesetz dar und werden diese Übertretungen von der Bezirksverwaltungs- behörde mit einer Geldstrafe bis zu € 7.270,00 oder mit Freiheitsstrafe bis zu vier Wochen geahndet. Der Bezirkshauptmann: Dr. Alexander Majcan (elektronisch gefertigt) 8330 Feldbach ● Bismarckstraße 11-13 Wir sind Montag bis Freitag von 8:00 bis 12:30 Uhr und nach telefonischer Vereinbarung für Sie erreichbar DVR https://datenschutz.stmk.gv.at ● UID ATU37001007 Steiermärkische Bank und Sparkassen AG: IBAN AT892081500006387633 ● BIC STSPAT2G EB_1 V1.1 2 Ergeht nachrichtlich an: 1. -

Empfohlene Bekämpfungsmaßnahmen

Bezirkskammer für Land- und Forstwirtschaft Leibnitz Referat: Pflanzenschutz Titel: Weinbau – Warnmeldung Nr. 5/19 ARZ Leibnitz, 26. Juni 2019 AMERIKANISCHE REBZIKADE: Erste Larven des dritten Larvenstadiums wurden in der letzten Woche (25. Kalenderwoche) im Zuge der Monitoringmaßnahmen des Landes Steiermark gefunden. Die Larven können ab diesem Stadium die Quarantänekrankheit Grapevine flavescence dorée (GFD, Goldgelbe Vergilbung) übertragen! Wegen der für Zikaden ungünstigen Wettersituation in der letzten Woche sind allerdings die Fangzahlen in den Weingärten im Vergleich zu den Vorwochen etwas zurückgegangen. Von verpflichtenden Maßnahmen zur Larvenbekämpfung wird daher vorerst abgesehen. Es wird aber dringend empfohlen, im Verbreitungsgebiet der Amerikanischen Rebzikade Maßnahmen gegen die Larven zu beginnen bzw. fortzuführen. Verbreitungsgebiet: Das Verbreitungsgebiet der ARZ umfasst folgende Gemeinden in den jeweiligen Bezirken: Bezirk Deutschlandsberg: Gemeinden Eibiswald, Pölfing-Brunn, St. Martin im Sulmtal und Wies Bezirk Hartberg-Fürstenfeld: Gemeinden Bad Blumau, Bad Waltersdorf, Buch-Sankt Magdalena, Ebersdorf, Fürstenfeld, Großwilfersdorf, Ilz, Loipersdorf bei Fürstenfeld, Ottendorf an der Rittschein und Söchau Bezirk Leibnitz: Gemeinden Arnfels, Ehrenhausen an der Weinstraße, Gamlitz, Gleinstätten, Großklein, Heimschuh, Kitzeck im Sausal, Leibnitz, Leutschach an der Weinstraße, Oberhaag, Sankt Andrä-Höch, Sankt Johann im Saggautal, Sankt Nikolai im Sausal, Sankt Veit in der Südsteiermark, Straß-Spielfeld, Tillmitsch und -

Wine from the Hills, with Hand & Heart © Flora P

Wine from the hills, with hand & heart © Flora P. The Steiermark’s winegrowers are poster children for TABLE OF CONTENTS steep slope viticulture, but also models of courageous reimagining. Seizing a historic opportunity, they conquered Austria with novel wine styles. Now, a new generation is blazing its own stylistic trails, reclaiming international renown for a region once known as the innovation hub of European viticulture. Three winegrowing regions, 4 Origin »Steiermark« 37 innumerable terroirs David Schildknecht Prelude: DAC 39 The short story about a long time 8 Gebietswein, the regional wines 40 Ortswein, the ace 41 Concerning the origins of 11 Ortswein: SüdsteiermarkDAC 42 great wines Ortswein: Vulkanland SteiermarkDAC 46 Ortswein: WeststeiermarkDAC 50 »Terroir Steiermark« 12 Riedenwein: a perspective 53 Geology & foundations 14 The taste of the Steiermark 56 The basis of soils 16 The palette of grape varieties 21 THE STEIERMARK PRÄDIKAT 58 Characteristic features of the climate 22 From the hills, with hand & heart The three winegrowing 26 Facts & figures 60 regions of the Steiermark Wine estates & traditional taverns 61 Origin »Steiermark« SüdsteiermarkDAC 27 Voices of the press 61 Vulkanland SteiermarkDAC 31 WeststeiermarkDAC 35 References 62 Contact 63 The Steiermark is a WINEGROWING REGION of great Three wine regions, importance, both for Austria and for Europe. Although industry strongly moulded the form and substance of innumerable terroirs the Steiermark in the middle of the 20th century and still dominates the ALPINE VALLEYS, the federal state itself has never abandoned its agrarian tradition, but has remained a region with a self-aware and SELF- ASSURED AGRICULTURAL SECTOR. The Steiermark is the second-greatest in area of Austria’s nine federal states, and is bordered to the south by Slovenia.