Article 89987 C10f26739707ff4f

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAEVIUS After Livius Andronicus, Naevius1 Was the Second

CHAPTER THREE NAEVIUS Dispositio. The Clash of Myth and History Double Identity: Campanian and Roman After Livius Andronicus, Naevius1 was the second Latin epic poet. He was of "Campanian" origin (Gellius 1. 20. 14), which, according to Latin usage, means that he was from Capua,2 a city allegedly founded by Romulus, and his thoughts and feelings were those of a Roman, not without a large admixture of Campanian pride. Capua in his day was almost as important economically as Rome and Carthage and its citizens were fully aware of this (though it was not until the Second Punic War that it abandoned Rome). Naevius himself tells us (Varro apud Gell. 17. 21. 45) that he actively participated in the First Punic War. The experience of that great historical conflict led to the birth of the Bellum Poenicum, the first Roman national epic. Similarly, Ennius would write his Annales after the Second Punic War and Virgil his Aeneid after the Civil Wars. In 235 B.C., only five years after the first performance of a Latin play by Livius Andronicus, Naevius staged a drama of his own. Soon he became the greatest comic playwright, unsurpassed until Plautus. He did not restrain his sharp tongue even when speaking of the noblest families. Although he did not mention anyone by name, he unequivocally alluded to a rather unheroic moment in the life of the young Scipio (Com. 108-110 R), and his quarrel with the Metelli (ps. Ascon., Ad Cic. Verr. 1. 29), formerly dismissed as fiction,3 is accepted today as having some basis in fact. -

TRADITIONAL POETRY and the ANNALES of QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A

REINVENTING EPIC: TRADITIONAL POETRY AND THE ANNALES OF QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS SEPTEMBER 2006 UMI Number: 3223832 UMI Microform 3223832 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © Copyright by John Francis Fisher, 2006. All rights reserved. ii Reinventing Epic: Traditional Poetry and the Annales of Quintus Ennius John Francis Fisher Abstract The present scholarship views the Annales of Quintus Ennius as a hybrid of the Latin Saturnian and Greek hexameter traditions. This configuration overlooks the influence of a larger and older tradition of Italic verbal art which manifests itself in documents such as the prayers preserved in Cato’s De agricultura in Latin, the Iguvine Tables in Umbrian, and documents in other Italic languages including Oscan and South Picene. These documents are marked by three salient features: alliterative doubling figures, figurae etymologicae, and a pool of traditional phraseology which may be traced back to Proto-Italic, the reconstructed ancestor of the Italic languages. A close examination of the fragments of the Annales reveals that all three of these markers of Italic verbal art are integral parts of the diction the poem. Ennius famously remarked that he possessed three hearts, one Latin, one Greek and one Oscan, which the second century writer Aulus Gellius understands as ability to speak three languages. -

The Maltese Islands and the Sea in Antiquity

THE MALTESE ISLANDS AND THE SEA IN ANTIQUITY The Maltese Islands and the Sea in Antiquity TIMMY GAMBIN The events of history often lead to the islands… F. Braudel THE STRETCHES OF SEA EXTANT BETWEEN ISLANDS AND mainland may be observed as having primary-dual functionalities: that of ‘isolating’ islands and that of providing connectivity with land masses that lay beyond the islands’ shores. On smaller islands especially, access to the sea provided a gateway from which people, goods and ideas could flow. This chapter explores how, via their surrounding seas, events of history often led to the islands of Malta and Gozo. The timeframe covered consists of over one thousand years (circa 700 BC to circa 400 AD); a fluid period that saw the island move in and out of the political, military and economic orbits of various powers that dominated the Mediterranean during these centuries. Another notion of duality can be observed in the interaction that plays out between those coming from the outside and those inhabiting the islands. It would be mistaken to analyze Maltese history solely in the context of great powers that touched upon and ‘colonized’ the islands. This historical narrative will also cover important aspects such as how the islands were perceived from those approaching from out at sea: were the islands a hazard, a haven or possibly both at one and the same time? It is also essential to look at how the sea was perceived by the islanders: did the sea bring welcome commercial activity to the islands shores; did it carry 1 THE MALTESE ISLANDS AND THE SEA pirate vessels and enemy ships? As important as these questions are, this narrative would be incomplete without reference to how the sea helped shape and mould the way in which the people living on Malta and Gozo chose (or were forced) to live. -

Latin Literature

Latin Literature By J. W. Mackail Latin Literature I. THE REPUBLIC. I. ORIGINS OF LATIN LITERATURE: EARLY EPIC AND TRAGEDY. To the Romans themselves, as they looked back two hundred years later, the beginnings of a real literature seemed definitely fixed in the generation which passed between the first and second Punic Wars. The peace of B.C. 241 closed an epoch throughout which the Roman Republic had been fighting for an assured place in the group of powers which controlled the Mediterranean world. This was now gained; and the pressure of Carthage once removed, Rome was left free to follow the natural expansion of her colonies and her commerce. Wealth and peace are comparative terms; it was in such wealth and peace as the cessation of the long and exhausting war with Carthage brought, that a leisured class began to form itself at Rome, which not only could take a certain interest in Greek literature, but felt in an indistinct way that it was their duty, as representing one of the great civilised powers, to have a substantial national culture of their own. That this new Latin literature must be based on that of Greece, went without saying; it was almost equally inevitable that its earliest forms should be in the shape of translations from that body of Greek poetry, epic and dramatic, which had for long established itself through all the Greek- speaking world as a common basis of culture. Latin literature, though artificial in a fuller sense than that of some other nations, did not escape the general law of all literatures, that they must begin by verse before they can go on to prose. -

Latin Literature 1

Latin Literature 1 Latin Literature The Project Gutenberg EBook of Latin Literature, by J. W. Mackail Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Latin Literature Author: J. W. Mackail Release Date: September, 2005 [EBook #8894] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on August 21, 2003] Edition: 10 Latin Literature 2 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO−8859−1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LATIN LITERATURE *** Produced by Distributed Proofreaders LATIN LITERATURE BY J. W. MACKAIL, Sometime Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford A history of Latin Literature was to have been written for this series of Manuals by the late Professor William Sellar. After his death I was asked, as one of his old pupils, to carry out the work which he had undertaken; and this book is now offered as a last tribute to the memory of my dear friend and master. -

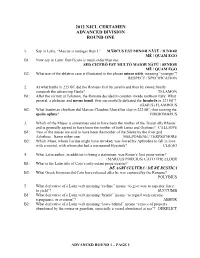

2012 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Say in Latin, “Marcus is younger than I.” MĀRCUS EST MINOR NĀTŪ / IUNIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B1: Now say in Latin: But Cicero is much older than me. SED CICERŌ EST MULTŌ MAIOR NĀTŪ / SENIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B2: What use of the ablative case is illustrated in the phrase minor nātū, meaning “younger”? RESPECT / SPECIFICATION 2. At what battle in 225 BC did the Romans first by javelin and then by sword finally vanquish the advancing Gauls? TELAMON B1: After the victory at Telamon, the Romans decided to counter-invade northern Italy. What general, a plebeian and novus homō, first successfully defeated the Insubrēs in 223 BC? (GAIUS) FLAMINIUS B2: What Insubrian chieftain did Marcus Claudius Marcellus slay in 222 BC, thus earning the spolia opīma? VIRIDOMARUS 3. Which of the Muses is sometimes said to have been the mother of the Trojan ally Rhesus and is generally agreed to have been the mother of both Linus and Orpheus? CALLIOPE B1: Two of the muses are said to have been the mother of the Sirens by the river god Achelous. Name either one. MELPOMENE / TERPSICHORE B2: Which Muse, whom Tacitus might have invoked, was forced by Aphrodite to fall in love with a mortal, with whom she had a son named Hyacinth? CL(E)IO 4. What Latin author, in addition to being a statesman, was Rome’s first prose writer? (MARCUS PORCIUS) CATO THE ELDER B1: What is the Latin title of Cato’s only extant prose treatise? DĒ AGRĪ CULTŪRĀ / DĒ RĒ RUSTICĀ B2: What Greek historian did Cato have released after he was captured by the Romans? POLYBIUS 5. -

Virgil and the Augustan Reception

VIR GIL AND THE AUGUSTAN R ECEPTION Richard F. Thomas Harvard University ab published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb22ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York ny 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, vic 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org ( Richard F. Thomas 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2001 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Bembo and New Hellenic Greek in `3B2' [ao] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 78288 0 hardback CONTENTS Acknowledgements ix Prologue xi Introduction: the critical landscape 1 1 Virgil and Augustus 25 2 Virgil and the poets: Horace, Ovid and Lucan 55 3 Other voices in Servius: schooldust of the ages 93 4 Dryden's Virgil and the politics of translation 122 5 Dido and her translators 154 6 Philology and textual cleansing 190 7 Virgil in a cold climate: fascist reception 222 8 Beyond the borders of Eboli: anti-fascist reception 260 9 Critical end games 278 Bibliography 297 Index 313 vii Introduction: the critical landscape In fact these writers are on the lookout for any double meanings, even where one of the meanings renders nonsense. -

2010 Advanced Certamen Finals

2010 TSJCL Certamen Advanced Level, Final Round TU#1: What two men stayed at the house of Diocles on their journey from Pylos to Sparta? TELEMACHUS / PEISISTRATUS B1: What seer does Telemachus bring back with him to Ithaca? THEOCLYMENUS B2: What other seer on Ithaca was an old friend of Odysseus? HALITHERSES TU#2: Octavius Mamilius led the opposition forces, while the Roman forces were led by Aulus Postumius Albinus. What was this battle that took place some time in the early 5th century BC? BATTLE OF LAKE REGILLUS B1: What leadership role was filled in the battle by Titus Aebutius Elva? MAGISTER EQUITUM / MASTER OF THE HORSE/CAVALRY COMMANDER B2: What unexpected maneuver by the cavalry does Livy say turned the tide of the battle in favor of the Romans? THE CAVALRY DISMOUNTED AND FOUGHT HAND-TO-HAND INSTEAD TU#3: According to his epitaph, supposedly written by the deceased author before he died, for whom should the divine Muses weep? (GNAEUS) NAEVIUS B1: According to this epitaph, what did the Romans forget how to do after Naevius' death? SPEAK LATIN B2: On his list of Rome's best comedic playwrights, where did Volcacius Sedigitus place Naevius? THIRD TU#4: Who forced visitors to work in his vineyard and was killed by Heracles? SYLEUS B1: Who compelled all visitors to compete with him in a reaping contest, and was killed by Heracles? LITYERSES B2: Who was rescued from Lityerses by Heracles as he was about to enter this reaping contest and surely would have been killed? DAPHNIS TU#5: Identify the Latin form dee (pronounced DEH - EH) which is presumed to have existed but does not appear in any extant Latin. -

Satire's Censorial Waters in Horace and Juvenal*

Satire’s Censorial Waters in Horace and Juvenal* KIRK FREUDENBURG ABSTRACT This paper concerns the water imagery of two iconic passages of Roman satire: Horace’s guration of Lucilius as a river churning with mud at Sat. 1.4.11, and the transformation of that image at Juvenal, Sat. 3.62–8 (the Orontes owing into the Tiber). It posits new ways of reckoning with the codications and further potentials of these images by establishing points of contact with the workings of water in the Roman world. The main point of reference will be to the work of Rome’s censors, who were charged not only with protecting the moral health of the state, but with ensuring the purity and abundance of the city’s water supply as well. Keywords: satire; water imagery; censor; Horace; Juvenal; Callimachus; Statius Symbolic waters have been charted in nearly every genre of ancient poetry. Rivers and springs have long histories as literary symbols in antiquity, and the passages of Greek and Roman poetry that feature poets guring their verses and voices as waters of various kinds (everything from crashing oods to tiny drops of dew) are too numerous to count. Augustan poetry is particularly rich in waters that signify, and that serve to spell out and particularise the qualities of the poems in which they gure; some of the more famous of these waters course through the satires of Horace (the Sermones ‘Conversations’).1 Despite drawing inspiration from a ‘foot-going muse’ (musa pedestris), for whom Helicon’s springs are generically out of reach, Horace uses images of water on frequent occasions in his satires not only to describe the emotional and poetic habits of his Sermones, their clarity, metrical ow and so on, but to gure their moral purposes, and to cast aspersions on those other poets who write in ‘turgid’ and ‘unbounded’ ways that are suggestive of a failure of self-control (verbal, metrical, emotional and otherwise). -

The Aeneid Virgil

The Aeneid Virgil TRANSLATED BY A. S. KLINE ROMAN ROADS MEDIA Classical education, from a Christian perspective, created for the homeschool. Roman Roads combines its technical expertise with the experience of established authorities in the field of classical education to create quality video courses and resources tailored to the homeschooler. Just as the first century roads of the Roman Empire were the physical means by which the early church spread the gospel far and wide, so Roman Roads Media uses today’s technology to bring timeless truth, goodness, and beauty into your home. By combining excellent instruction augmented with visual aids and examples, we help inspire in your children a lifelong love of learning. The Aeneid by Virgil translated by A. S. Kline This text was designed to accompany Roman Roads Media's 4-year video course Old Western Culture: A Christian Approach to the Great Books. For more information visit: www.romanroadsmedia.com. Other video courses by Roman Roads Media include: Grammar of Poetry featuring Matt Whitling Introductory Logic taught by Jim Nance Intermediate Logic taught by Jim Nance French Cuisine taught by Francis Foucachon Copyright © 2015 by Roman Roads Media, LLC Roman Roads Media 739 S Hayes St, Moscow, Idaho 83843 A ROMAN ROADS ETEXT The Aeneid Virgil TRANSLATED BY H. R. FAIRCLOUGH BOOK I Bk I:1-11 Invocation to the Muse I sing of arms and the man, he who, exiled by fate, first came from the coast of Troy to Italy, and to Lavinian shores – hurled about endlessly by land and sea, by the will of the gods, by cruel Juno’s remorseless anger, long suffering also in war, until he founded a city and brought his gods to Latium: from that the Latin people came, the lords of Alba Longa, the walls of noble Rome. -

Loeb Classical Library

LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY 2017–2018 Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON NEW TITLES FRAGMENTARY GALEN REPUBLICAN LATIN Hygiene Ennius EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY IAN JOHNSTON • SANDER M. GOLDBERG Galen of Pergamum (129–?199/216), physician GESINE MANUWALD to the court of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, Quintus Ennius (239–169 BC), widely was a philosopher, scientist, medical historian, regarded as the father of Roman literature, theoretician, and practitioner who wrote on an was instrumental in creating a new Roman astonishing range of subjects and whose literary identity and inspired major impact on later eras rivaled that of Aristotle. developments in Roman religion, His treatise Hygiene, also known social organization, and popular as “On the Preservation of Health” culture. This two-volume edition (De sanitate tuenda), was written of Ennius, which inaugurates during one of Galen’s most prolific the Loeb series Fragmentary periods (170–180) and ranks among Republican Latin, replaces that his most important and influential of Warmington in Remains of Old works, providing a comprehensive Latin, Volume I and offers fresh account of the practice of texts, translations, and annotation preventive medicine that still that are fully current with modern has relevance today. scholarship. L535 Vol. I: Books 1–4 2018 515 pp. L294 Vol. I: Ennius, Testimonia. L536 Vol. II: Books 5–6. Thrasybulus. Epic Fragments 2018 475 pp. On Exercise with a Small Ball L537 Vol. II: Ennius, Dramatic 2018 401 pp. Fragments. Minor Works 2018 450 pp. APULEIUS LIVY Apologia. Florida. De Deo Socratis History of Rome EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY CHRISTOPHER P. -

Cato the Censor and the Beginnings of Latin Prose

Cato the Censor and the Beginnings of Latin Prose Cato the Censor and the Beginnings of Latin Prose FROM POETIC TRANSLATION TO ELITE TRANSCRIPTION Enrica Sciarrino THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS · COLUMBUS Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sciarrino, Enrica, 1968– Cato the Censor and the beginnings of Latin prose : from poetic translation to elite tran- scription / Enrica Sciarrino. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1165-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1165-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9266-2 (cd-rom) 1. Latin prose literature—History and criticism. 2. Cato, Marcus Porcius, 234–149 B.C.—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PA6081.S35 2011 878'.01—dc22 2011006020 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1165-6) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9266-2) Cover design by Mia Risberg. Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Typeset in Times New Roman. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI 39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Preface and Acknowledgments vii List of Abbreviations xi Chapter 1 Situating the Beginnings of Latin Prose 1 Chapter 2 Under the Roman Sun: Poets, Rulers, Translations, and Power 38 Chapter 3 Conflicting Scenarios: Traffic in Others and Others’ Things 78 Chapter 4 Inventing Latin Prose: Cato the Censor and the Formation of a New Aristocracy 117 Chapter 5 Power Differentials in Writing: Texts and Authority 161 Conclusion 203 Bibliography 209 Index Locorum 229 General Index 231 Preface and Acknowledgments his book treats a moment in Roman cultural history that in the last decade or so has become one of the most contentious areas of dis- T cussion in classical scholarship.