Etd Nlw8.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Monthly 2018 College Rankings

The Prison-to-School Pipeline 2018 COLLEGE RANKINGS What Can College Do For You? PLUS: The best—and worst— colleges for vocational certificates Which colleges encourage their students to vote? Why colleges should treat SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN students like numbers All Information Fixing higher education deserts herein is confidential and embargoed Everything you always wanted to know through Aug. 23, 2018 about higher education policy VOLUME 50 NUMBER 9/10 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 SOCIAL MOBILITY RESEARCH SERVICE Features NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES THE 2018 COLLEGE GUIDE *Public institution Introduction: A Different Kind of College Ranking 15 °For-profit institution by Kevin Carey America’s Best and Worst Colleges for%offederalwork-studyfunds Vocational Certificates 20 GraduationGrad rate rate rank performancePell graduationPell rank performance gap rankFirst-gen rank performancerankEarningsperformancerankNoNetpricerank publicationRepaymentrankPredictedrepaymentraterankResearch has expendituresBachelor’stoPhDrank everScience&engineeringPhDsrank rank rankedFacultyawardsrankFacultyinNationalAcademiesrank thePeaceCorpsrank schoolsROTC rank wherespentonservicerankMatchesAmeriCorpsservicegrants? millionsVotingengagementpoints of Americans 1 Harvard University (MA) 3 35 60 140 41 2seek 5 168 job310 skills.8 Until10 now.17 1 4 130 188 22 NO 4 2 Stanford University (CA) 7 128 107 146 55 11 by2 Paul16 48Glastris7 6 7 2 2 70 232 18 NO 1 3 MA Institute of Technology (MA) 16 234 177 64 48 7 17 8 89 13 2 10 3 3 270 17 276 NO 0 4 Princeton University (NJ) 1 119 100 100 23 20 Best3 30 &90 Worst67 Vocational5 40 6 5 Certificate117 106 203 ProgramsNO 1 Rankings 22 5 Yale University (CT) 4 138 28 121 49 22 America’s8 22 87 18Best3 Colleges39 7 9 for134 Student22 189 VotingNO 0 28 6 Duke University (NC) 9 202 19 156 218 18 Our26 15 first-of-its-kind183 6 12 list37 of9 the15 schools44 49doing215 theNO most3 to turn students into citizens. -

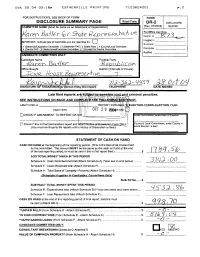

13 17S 1 Lu "UNPAID BILLS (From Schedule D - Attach Schedule D)

Oct 29 04 03 :18p ESTHERVILLE PRINTING 7123624201 p .2 FOR INSTRUCTIONS, SEE BACK OF FORM FORM DISCLOSURE SUMMARY PAGE DR-2 I DISCLOSURE COMMITTEE NAME (Must be same as on Statement of Organization) (Rev . 07/2003) REPORT For Office Use Only Comm . # Logged In IMPORTANT: Indicate type of committee you are reporting for 1-1 Scanned (t )Statewide/Legislative Candidate (2 )Statewide PAC( 3 )State Party (4 )CountyA-ocal Candidate (5 )County PAC ( 6 )Ballot IssuelFranchise Committee (7 )County/City Central Committee Computer -_-~ Audited CANDIDATE COMMITTEES ONLY: Candidate Name Political Party ~_~ rtvr, 8~L:41Er RPbfut~r`;'rT;th Office Sought District (if Senate or House) U110- to I? 7<eonc' 7 SIGNATURE Or TEE-Rio-ierson filing this report) TELEPHONE DATE SIGNED Late filed reports ar nd criminal penalties. SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON BACK AND COIV1 NCE: ELECTION l(2)NON-ELECTION YEAR. [CHECK IF AMENDMENT TO REPORT DAT~d L Local Committees, enter Date of Election L [~ Check if this is final (termination) report and atta orm DR-3 County & Local Committees, enter County in which is held (You must continue to file reports until a Notice of Dissolution is filed.) Election STATEMENT OF CASH ON HAND CASH ON HAND at the beginning of the reporting period . (This is the total of all monies held by the committee, This amount MUST be the same as the cash on hand at the end of the last reporting period, or must be zero if this is first report filed.) .. .. ..... ..... .. .. ... ... .. ... .. $ ADD TOTAL MONEY TAKEN IN THIS PERIOD Schedule A: Cash Contribufions total (Attach Schedule A) (`also see in-kind below) .. -

Overuse White Paper Formatted

White Paper Series Ranking and analysis of overuse in U.S. hospitals EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Overuse, which is also known as low-value care, is often defined as the provision of health care services for which the potential for harm exceeds the likely benefit to a patient. Overuse occurs in all healthcare settings, including hospitals. It exposes patients to preventable harm and wastes more than $100 billion each year. To date, no study has published the rate of overuse in specific U.S. hospitals. The Lown Institute Hospital Index is the first hospital ranking to grade individual hospitals by how well they avoid overuse. This white paper provides an analysis of the overuse of 13 low-value services in 3,282 U.S. hospitals using Medicare data. These 13 services include imaging tests, surgeries, and cardiovascular procedures, and have all been validated in previous studies of low-value care. Only instances of these services deemed inappropriate in the literature were counted as overuse. Hospitals that did not have the capacity to perform a specific low-value procedure did not have that service counted in their total grade. We find that overuse varies across hospitals by type, size, and location. Teaching hospitals, larger hospitals, urban hospitals, and for-profit hospitals on average ranked lower for avoiding overuse overall, compared to non-teaching, smaller, rural hospitals. However, these patterns were not always consistent across all low-value services. Safety net hospitals and small rural hospitals had higher rankings in avoiding overuse overall, but their scores differed by specific low-value service. For-profit hospitals consistently ranked lower than nonprofit hospitals for avoiding nearly every low-value service measured. -

Expert Suggests Jetty on Sanibel at Blind Pass City Offers —See Page 3 by Pete Bishop Planning Talks • Staff Writer Short-Term Sambel Planning Dr

REPORTER Week of March 15-21,2001 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 28, NUMBER 11, 32 PAGES 75 CENTS Ikki signing Fire damages two island businesses Aitist Ikki Matsumoto to By Anne Bellew earth are they doing delivering AT LEFT: The outside of sign his Island Repoiter Staff writer stuff to the restaurant at this hour poster foi subsuihers at the Pippens escaped dam- Sambel Oallciy lomonow. of the morning'?' (Wagner lives age. Photo Muhavl Pisti Hit A fire in the early morning right behind Tahitian Gardens and, hours Saturday, March 10, —See page 19 over the years, the residents of BELOW: A view into the destroyed the kitchen in Pippin's Roseate Lane have complained kitchen of Pippin's restaurant, and fire-related damage about noise from the various Restaurant.^"'" <owu .v <•>/ devastated the owner of an adja- restaurants that have inhabited the Sambt'l Fin Ar Ri'scuc Di^lntt cent gift shop who had intended to Pippin's location.) close the sale of her store just two "The dispatcher was very calm, days later. soothing and nice," she continued, Church shows pbns The tire, which is still under "and told me that the noise was Tlie Sambel Community investigation, is believed to be of fire engines. There was a fire at Church has submitted a electrical origin from the restau- Pippin's." modified site plan foi its rant's kitchen. The restaurant Initially, the fiist alarm came proposed relocation and anchois the Tahitian Gardens from the restaurant's automatic expansion. shopping center. burglar alaim and alerted the "I called the police department Sanibel Police Department. -

Hourglass 05-27-06 .Indd

SSgt.gt. MMichaelichael KKnight,night, lleft,eft, ssupportsupports CCpl.pl. DDennisonennison MMuczynski,uczynski, iinn a lliveive fi rree ooff a SStingertinger mmissileissile TThursday.hursday. TThehe 11stst SStingertinger BBatteryattery MMarinesarines aarrivedrrived oonn MMonday,onday, ttrainedrained oonn MMeckeck oonn WWednesdayednesday aandnd TThursdayhursday aandnd ddepartedeparted ttoday.oday. ((PhotoPhoto bbyy NNellell DDrumheller)rumheller) wwww.smdc.army.mil/KWAJ/Hourglass/hourglass.htmlww.smdc.army.mil/KWAJ/Hourglass/hourglass.html COMMENTARY Thirty minutes isn’t so much to give Do you like numbers, facts and If those are added up, that’s fi gures? 1,011,571 American military members I did some research courtesy of the who have died for freedom. Internet and found some you might like And that’s just the ‘major’ wars to know. America has fought, although I guess Are you ready? any war is major to the ones who are There were 10,623 Continental Army fi ghting and dying in it. Soldiers killed in the American Revolu- There’s another number that should tionary War; The War of 1812 claimed be noted. That’s the 30 minutes it will 6,765 Americans; 13,283 Americans take to hold the Memorial Day cer- died in the Mexican War; 359,528 federal Soldiers died in emony starting at 9 a.m., Monday, at the fl ag poles. the Civil War preserving the Union; 2,446 Americans died There are many things to do on a day off. Diving, fi sh- in the Spanish-American War; World War I saw 116,708 ing, picnics and going to the beach or pool. I hope that Americans killed; World War II took 407,316 American lives; quite a few folks can also fi nd time to attend the ceremony 33,651 Americans died in the Korean War; 58,438 Ameri- this year, especially since many of our young and not-so- cans were killed in Vietnam; 293 Americans died in the Gulf young men and women are giving their all right now in War and more than 2,500 Americans have died in Afghani- stan and Iraq so far. -

History Early History

Cable News Network, almost always referred to by its initialism CNN, is a U.S. cable newsnetwork founded in 1980 by Ted Turner.[1][2] Upon its launch, CNN was the first network to provide 24-hour television news coverage,[3] and the first all-news television network in the United States.[4]While the news network has numerous affiliates, CNN primarily broadcasts from its headquarters at the CNN Center in Atlanta, the Time Warner Center in New York City, and studios in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. CNN is owned by parent company Time Warner, and the U.S. news network is a division of the Turner Broadcasting System.[5] CNN is sometimes referred to as CNN/U.S. to distinguish the North American channel from its international counterpart, CNN International. As of June 2008, CNN is available in over 93 million U.S. households.[6] Broadcast coverage extends to over 890,000 American hotel rooms,[6] and the U.S broadcast is also shown in Canada. Globally, CNN programming airs through CNN International, which can be seen by viewers in over 212 countries and territories.[7] In terms of regular viewers (Nielsen ratings), CNN rates as the United States' number two cable news network and has the most unique viewers (Nielsen Cume Ratings).[8] History Early history CNN's first broadcast with David Walkerand Lois Hart on June 1, 1980. Main article: History of CNN: 1980-2003 The Cable News Network was launched at 5:00 p.m. EST on Sunday June 1, 1980. After an introduction by Ted Turner, the husband and wife team of David Walker and Lois Hart anchored the first newscast.[9] Since its debut, CNN has expanded its reach to a number of cable and satellite television networks, several web sites, specialized closed-circuit networks (such as CNN Airport Network), and a radio network. -

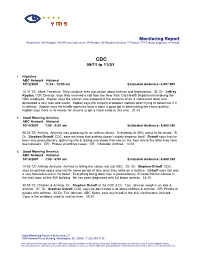

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual CDC 09/11 to 11/01 1. Nightline ABC Network National 10/12/2001 11:35 - 12:05 am Estimated Audience: 4,997,900 15.37 TZ; More Terrorism. They continue their discussion about anthrax and bioterrorism. SI; Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, CDC Director, says they received a call from the New York City Health Department involving the NBC employee. Koplan says the woman was exposed to the contents of an ill intentioned letter and developed a skin rash and lesion. Koplan says the amount of powder matters when trying to determine if it is anthrax. Koplan says the health agencies have a done a good job in determining the cases quickly. Koplan says there is no reason for anyone to get a nasal swab at this time. 21.42 2. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/15/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 08.23 TZ; Anthrax. America was preparing for an anthrax attack. Everybody at NBC wants to be tested. SI; Dr. Stephen Ostroff, CDC, says we know that anthrax doesn't widely disperse itself. Ostroff says they've been very precautionary, gathering info & testing everybody that was on the floor where the letter may have been present. GR; Photos of anthrax cases. GR; Inhalation Anthrax. 13.04 3. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/16/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 14.50 TZ; Anthrax Analysis. -

Sample Draft Syllabus

CREATING THE AMERICAN METROPOLIS Loyola University Chicago Prof. Timothy J. Gilfoyle HIST 386, Sec. 204 511 Crown Fall 2018 (773) 508-2221 Tuesday, 2:30-5 p.m. E-mail: [email protected] Corboy Law Center, Room L08 Office Hours: MW, 9-10am, 11:30am-2pm http://luc.edu/history/people/facultyandstaffdirectory/timothyjgilfoyle.shtml "God made the country and man made the town." William Cowper, 1780 The United States was born in the country and moved to the city. This course examines the transformation of the United States from a simple agrarian and small-town society to a complex urban and suburban nation. Field trips and walking tours are a vital component of the class. Between 1850 and 1950, American urban communities were transformed from "horizontal" cities of row houses, tenements and factories to "vertical" cities of apartments and skyscrapers. From New York's Brooklyn Bridge to Chicago's Sears Tower to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge, the tower and the bridge epitomized American urbanism, and frequently America itself. Certain themes recur throughout the course of American urban and cultural history which will be focal points of this class: the interaction of private commerce with cultural change; the rise of distinctive working and middle classes; the creation and segregation of public and private spaces; 1 Sample Draft Syllabus the formation of new and distinctive urban subcultures organized by gender, work, race, religion, ethnicity, and sexuality; problems of health and housing resulting from congestion; and blatant social divisions among wealthy, poor, native-born, immigrant, and racial groups. More broadly, the course attempts to comprehend the American city within the changing questions of what it means to be an American. -

Growth Management and the City

Growth Management and the City James A. Kushnert The way urban growth has been "managed," it is no surprise that Amer- ica's cities are dying.' During the last three decades, American urban growth policy was directed to suburban growth. Government encouraged exodus from the metropolis through: deep subsidies for highways, utilities, and open space; housing finance, particularly in the form of tax deductions for mortgage interest and real property taxes; and subsidized Veteran's Administration loans and Federal Housing Administration mortgage insurance.2 Leaving the city in search of suburban values, the affluent were followed by industry in search of greener locations, retail establishments that favor malls, and restaurants and entertainment outlets looking for secure locations. Thus, the economic base from which taxes are generated to fund public services was transferred to the suburbs. Despite notable, symbolic, and often exciting urban renewal projects, the suburban growth explosion left distinct patterns of systemic poverty in the cities. These patterns include: racial segregation, burgeoning crime, inadequate transit systems, decaying neighborhoods and housing stock, declining school systems, inadequate job training, high unemployment, rapid population expan- sion, minimal employment creation, and inadequate systems of public safety and health. America's urban streets and parks are often unsafe, and urban transit systems, bridges, water and sewer lines, and public buildings need extensive rebuilding. The situation requires both massive reallocation of the tax base and an escalation in taxing and spending on public works, human services, and job creation rivaling the scale of the New Deal. Without this radical alteration of America's urban policy, together with public safety initiatives reflecting a wartime mobilization, the American metropolis-indeed the nation-will be doomed to a declining quality of life that leads to eventual third world economic status. -

Instructor's Resource Manual on Social Problems

Instructor’s Resource Manual on Social Problems Third Edition Compiled and Edited by Lutz Kaelber University of Vermont and Walter Carroll Bridgewater State College AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION 1307 New York Avenue NW #700 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 383-9005 ASA Resource Materials for Teaching Copyright 2001 THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION Documents distributed by the American Sociological Association are not intended to represent the official position of the American Sociological Association. Instead, they constitute a medium by which colleagues may communicate with each other to improve the teaching of sociology. Table of Contents _____________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Essay: Teaching Social Problems ........................................................................................................1 Syllabi .........................................................................................................................................................................11 Walter F. Carroll, Bridgewater State College..............................................................................................................13 James A. Crone, Hanover College...............................................................................................................................16 Brenda Forster, Elmhurst College ...............................................................................................................................21 -

The “Regular Order”: a Perspective

The “Regular Order”: A Perspective November 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46597 SUMMARY R46597 The “Regular Order”: A Perspective November 6, 2020 Many contemporary lawmakers urge a return to “regular order” lawmaking. In general, the regular order refers to a traditional, committee-centered process of lawmaking, very Walter J. Oleszek much in evidence during most of the 20th century. Today, Congress has evolved to Senior Specialist in become largely a party-centered institution. Committees remain important, but they are American National less important than previously as “gatekeepers” to the floor. This development Government represents a fundamental “then and now” change in the power dynamics of Capitol Hill. Regular order is generally viewed as a systematic, step-by-step lawmaking process that emphasizes the role of committees: bill introduction and referral to committee; the conduct of committee hearings, markups, and reports on legislation; House and Senate floor consideration of committee-reported measures; and the creation of conference committees to resolve bicameral differences. Many Members and commentators view this sequential pattern as the ideal or “best practices” way to craft the nation’s laws. Regular order is a lawmaking process that promotes transparency, deliberation, and the wide participation of Members in policy formulation. Significant deviations from the textbook model of legislating—common in this party-centric period—might be called “irregular,” “nontraditional,” “unorthodox,” or “unconventional” lawmaking. The well- known “Schoolhouse Rock” model of legislating still occurs, but its prominence has declined compared with the rise of newer, party leadership-directed processes. Regular or irregular procedures can successfully be used to translate ideas into laws. -

The Missing Account of Progressive Corporate Criminal Law

Department of Criminology Working Paper No. 2017-5.0 The Missing Account of Progressive Corporate Criminal Law William S. Laufer This paper can be downloaded from the Penn Criminology Working Papers Collection: http://crim.upenn.edu THE MISSING ACCOUNT OF PROGRESSIVE CORPORATE CRIMINAL LAW William S. Laufer* INTRODUCTION This seems to be an ideal time to revisit the normative, doctrinal, and policy-laden foundations of the corporate criminal law. With renewed calls for a repeal of the most costly of corporate regulations and reforms, it is tempting to speculate about the future of corporate compliance and corporate criminal liability.1 A host of academics continue to worry about the many hard-to-quantify direct and collateral costs of corporate criminal liability.2 Regulators and legislators still question whether some financial institutions are too big to prosecute, take to trial, and convict.3 The general public fears *Julian Aresty Professor, Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics, Sociology, and Criminology; Director, Carol and Lawrence Zicklin Center; The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania (J.D., Ph.D.). Thanks to Vik Khanna, Jennifer Arlen, Sally Simpson, John Hagan, Eric Orts, Peter Conti-Brown, Mihailis E. Diamantis, Ron Levine, Steve Solow, Kip Schlegel, Eduardo Saad Diniz, and Dominik Brodowski for comments on earlier versions of this article. My appreciation to Serina Vash and The Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement at NYU Law School for their post of this Article. 1 See, e.g., Tom Fox, TRUMP AND