Space and Its Representation in Moral Panics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 13ᵗʰ Annual Women's Leadership Conference

The 13ᵗʰ Annual Women's Leadership Conference Presented by The MGM Resorts Foundation: Dr. Mary Kelly Joins as Featured Leadership Expert, Innovative Journalist Natalie Allen Returns as Conference Host LAS VEGAS, June 7, 2019 /PRNewswire/ -- The MGM Resorts Foundation is pleased to announce the following guest speakers at this year's 13th Annual Women's Leadership Conference (WLC): Dr. Mary Kelly, internationally known economist and leadership expert; and returning WLC host Natalie Allen, anchor for CNN International. The conference will be held Aug. 5 & 6 at MGM Grand Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, NV. Dr. Mary Kelly Mary Kelly, PhD, CSP, CDR, US Navy (ret) is CEO of Productive Leaders, specializing in leadership, productivity, communication and business profit growth. In 21 years as a Navy intelligence and logistics officer, she ran military bases and trained more than 40,000 military and civilian personnel. She gained extensive experience in human resources, finance, insurance, organizational leadership, strategic planning and project development. Dr. Kelly focuses on building successful strategies for business leaders at all levels of an organization. She has earned an outstanding reputation as a leadership expert and charismatic speaker, known for translating leadership theory into actual how-to-make-it- happen practice, with real life tools and takeaways. She has authored 11 books on business growth and leadership, including Why Leaders Fail and the 7 Prescriptions for Success, In Case of Emergency Break Glass! and 15 Ways to Grow Your Business in Every Economy. She has been quoted in hundreds of periodicals including Forbes, Money Magazine, Yahoo Finance, Entrepreneur and many business journals. -

Natalie Allen, CNN International Anchor and Correspondent, Returns to Host 2017 WLC

NEWS RELEASE Natalie Allen, CNN International Anchor and Correspondent, Returns to Host 2017 WLC 4/18/2017 The conference, which offers workshops on career advancement, entrepreneurship and tips on work/life balance, has sold out for the past three years. LAS VEGAS, April 18, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- Award-winning broadcast journalist Natalie Allen will return as host of the MGM Resorts Foundation's 11th annual Women's Leadership Conference (WLC) Aug. 7-8 at MGM Grand Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, NV. Sponsored by the nonprofit MGM Resorts Foundation, the two-day conference strives to provide women with the developmental tools they need to advance their lives and careers. Each year, the event's proceeds, after costs, are donated to a local nonprofit that is devoted to the welfare and development of women and girls. This will be Ms. Allen's fourth year hosting the conference. Organizers say her energy and stage presence have added depth to the popular event, which has attracted sell-out crowds for the past three years. "Natalie is dynamic on stage," says conference organizer Dawn Christensen, director of National Diversity Relations for MGM Resorts International. "Whether she's sharing a personal anecdote from the podium or moderating a panel, she does a great job of connecting with the audience. We're thrilled that she's hosting again." Last year, registration for the conference sold out days in advance, with more than 1,000 signing up to attend. Organizers encourage early registration to those who plan to attend in 2017. "I love hosting this conference," Ms. Allen says. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Correlates of Imaginative Suggestibility and Hypnotizability in Children

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2000 Correlates of imaginative suggestibility and hypnotizability in children. Bruce C. Poulsen University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Poulsen, Bruce C., "Correlates of imaginative suggestibility and hypnotizability in children." (2000). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1271. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1271 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORRELATES OF IMAGINATIVE SUGGESTIBILITY AND HYPNOTIZABILITY IN CHILDREN A Dissertation Presented by BRUCE C. POULSEN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2000 Education © Copyright by Bruce Craig Poulsen 2000 All Rights Reserved CORRELATES OF IMAGINATIVE SUGGESTIBILITY AND HYPNOTIZABILITY IN CHILDREN A Dissertation Presented by BRUCE C. POULSEN B^\ty W. Jackson, Dean S^hqol of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance and support of several individuals, without whom this project would not have been possible. First, I am indebted to William Matthews, Jr., Ph.D. and Irving Kirsch, Ph.D. for mitial suggestions for both the research design and statistical analysis. Karen Olness, M.D. and Steven Jay Lynn, Ph.D. both provided helpful suggestions for selecting the measurement instruments. Several individuals at Primary Children's Medical Center provided invaluable support during the data collection procedures. -

When the Truth Hurts: Relations Between Psychopathic Traits

WHEN THE TRUTH HURTS: RELATIONS BETWEEN PSYCHOPATHIC TRAITS AND THE WILLINGNESS TO TELL VARIED TYPES OF LIES by Dominique Gutierrez, B.S. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a Major in Research Psychology May 2021 Committee Members: Katherine Warnell, Chair Randall Osborne Jessica Perrotte COPYRIGHT by Dominique Gutierrez 2021 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Dominique Gutierrez, refuse permission to copy in excess of the “Fair Use” exemption without my written permission. DEDICATION To my brother, who I wish could have read this. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge first my loving parents, without whom I would not have been able to make it this far. Your support of and dedication to me has been a crucial part of my learning and I thank you wholeheartedly. I would also like to acknowledge my friends and cohort for your overwhelming support. There are too many people to list here, but you know who you are. From taking early drafts of my study and nagging me to do homework, to lending an ear when I vented about the drag of school, you have been there for me in too many ways to count. -

Gaslighting, Misogyny, and Psychological Oppression Cynthia A

The Monist, 2019, 102, 221–235 doi: 10.1093/monist/onz007 Article Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/monist/article-abstract/102/2/221/5374582 by University of Utah user on 11 March 2019 Gaslighting, Misogyny, and Psychological Oppression Cynthia A. Stark* ABSTRACT This paper develops a notion of manipulative gaslighting, which is designed to capture something not captured by epistemic gaslighting, namely the intent to undermine women by denying their testimony about harms done to them by men. Manipulative gaslighting, I propose, consists in getting someone to doubt her testimony by challeng- ing its credibility using two tactics: “sidestepping” (dodging evidence that supports her testimony) and “displacing” (attributing to her cognitive or characterological defects). I explain how manipulative gaslighting is distinct from (mere) reasonable disagree- ment, with which it is sometimes confused. I also argue for three further claims: that manipulative gaslighting is a method of enacting misogyny, that it is often a collective phenomenon, and, as collective, qualifies as a mode of psychological oppression. The term “gaslighting” has recently entered the philosophical lexicon. The literature on gaslighting has two strands. In one, gaslighting is characterized as a form of testi- monial injustice. As such, it is a distinctively epistemic injustice that wrongs persons primarily as knowers.1 Gaslighting occurs when someone denies, on the basis of another’s social identity, her testimony about a harm or wrong done to her.2 In the other strand, gaslighting is described as a form of wrongful manipulation and, indeed, a form of emotional abuse. This use follows the use of “gaslighting” in therapeutic practice.3 On this account, the aim of gaslighting is to get another to see her own plausible perceptions, beliefs, or memories as groundless.4 In what follows, I develop a notion of manipulative gaslighting, which I believe is necessary to capture a social phenomenon not accounted for by epistemic gaslight- ing. -

13 17S 1 Lu "UNPAID BILLS (From Schedule D - Attach Schedule D)

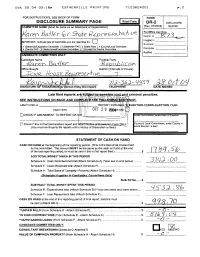

Oct 29 04 03 :18p ESTHERVILLE PRINTING 7123624201 p .2 FOR INSTRUCTIONS, SEE BACK OF FORM FORM DISCLOSURE SUMMARY PAGE DR-2 I DISCLOSURE COMMITTEE NAME (Must be same as on Statement of Organization) (Rev . 07/2003) REPORT For Office Use Only Comm . # Logged In IMPORTANT: Indicate type of committee you are reporting for 1-1 Scanned (t )Statewide/Legislative Candidate (2 )Statewide PAC( 3 )State Party (4 )CountyA-ocal Candidate (5 )County PAC ( 6 )Ballot IssuelFranchise Committee (7 )County/City Central Committee Computer -_-~ Audited CANDIDATE COMMITTEES ONLY: Candidate Name Political Party ~_~ rtvr, 8~L:41Er RPbfut~r`;'rT;th Office Sought District (if Senate or House) U110- to I? 7<eonc' 7 SIGNATURE Or TEE-Rio-ierson filing this report) TELEPHONE DATE SIGNED Late filed reports ar nd criminal penalties. SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON BACK AND COIV1 NCE: ELECTION l(2)NON-ELECTION YEAR. [CHECK IF AMENDMENT TO REPORT DAT~d L Local Committees, enter Date of Election L [~ Check if this is final (termination) report and atta orm DR-3 County & Local Committees, enter County in which is held (You must continue to file reports until a Notice of Dissolution is filed.) Election STATEMENT OF CASH ON HAND CASH ON HAND at the beginning of the reporting period . (This is the total of all monies held by the committee, This amount MUST be the same as the cash on hand at the end of the last reporting period, or must be zero if this is first report filed.) .. .. ..... ..... .. .. ... ... .. ... .. $ ADD TOTAL MONEY TAKEN IN THIS PERIOD Schedule A: Cash Contribufions total (Attach Schedule A) (`also see in-kind below) .. -

AMERICA's CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 11

t I l AlLY r .... )k.fl ~FS A Ot:l ) lO~Ol R.. Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W. Yale-Loehr • M I GRAT i o~]~In AMERICA'S CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity after September 11 .. AUTHORS Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W . Yale-Loehr MPI gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton in the preparation of this report. Copyright © 2003 Migration Policy Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Migration Policy Institute. Migration Policy Institute Tel: 202-266-1940 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300 Fax:202-266-1900 Washington, DC 20036 USA www.migrationpolicy.org Printed in the United States of America Interior design by Creative Media Group at Corporate Press. Text set in Adobe Caslon Regular. "The very qualities that bring immigrants and refugees to this country in the thousands every day, made us vulnerable to the attack of September 11, but those are also the qualities that will make us victorious and unvanquished in the end." U.S. Solicitor General Theodore Olson Speech to the Federalist Society, Nov. 16, 2001. Mr. Olson's wife Barbara was one of the airplane passengers murdered on September 11. America's Challenge: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 1 1 Table of Contents Foreword -

It's Official

ALUMNI TRAVEL WRITERS It’s Official \ CHARLES WHITAKER JEFFREY ZUCKER SCHOLARSHIPS IS DEAN OF MEDILL \ IMC IN SAN FRANCISCO SUMMER/FALL 2019 \ ISSUE 101 \ ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTENTS \ Congratulations to Max Bearak EDITORIAL STAFF DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI of the Washington Post RELATIONS AND ENGAGEMENT Belinda Lichty Clarke (MSJ94) MANAGING EDITOR Winner of the 2018 James Foley Katherine Dempsey (BSJ15, MSJ15) DESIGN Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism Amanda Good COVER PHOTOGRAPHER Colin Boyle (BSJ20) PHOTOGRAPHER Jenna Braunstein CONTRIBUTORS Erin Chan Ding (BSJ03) Kaitlyn Thompson (BSJ11, IMC17) Nikhila Natarajan (IMC19) Mary Neil Crosby (MSJ89) 11 MEDILL HALL OF 18 THINKING ACHIEVEMENT CLEARLY ABOUT 2019 INDUCTEES MARTECH Medill welcomes five inductees Course in San Francisco into its Hall of Achievement. helps students ask the right MarTech questions. 14 JEFFREY ZUCKER SCHOLARSHIPS 20 MEDILLIAN Two new funds aim to TRAVEL foster the next generation WRITERS of journalists. Alumni work in travel-focused positions that encourage others to explore the world. 16 MEDILL WOMEN The Nairobi Bureau Chief won for his reporting from sub-Saharan Africa. IN MARKETING PANEL 24 AN AMERICAN His stories from Congo, Niger and Zimbabwe chronicled a wide range of SUMMER Panel event with female extreme events that required intense bravery in dangerous situations PLEASE SEND STORY PITCHES alumni provides career advice. Faculty member Alex AND LETTERS TO: Kotlowitz sheds light on without being reckless or putting himself at the center of the story, new book. 1845 Sheridan Rd. said the judges, who were unanimous in their decision. Evanston, IL 60208 [email protected] 5 MEDILL NEWS / 26 CLASS NOTES / 30 OBITUARIES / 36 KEEP READING .. -

Targeted Violence and Public Security

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts REACTION RHETORICS: TARGETED VIOLENCE AND PUBLIC SECURITY A Dissertation in Communication Arts & Sciences by Bradley A. Serber © 2016 Bradley A. Serber Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2016 ii The dissertation of Bradley A. Serber was reviewed and approved* by the following: Rosa A. Eberly Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and English Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Stephen H. Browne Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Jeremy Engels Associate Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences Kirt H. Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Greg Eghigian Associate Professor of Modern History Denise Haunani Solomon Liberal Arts Research Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences Head of the Department of Communication Arts and Sciences *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how members of various publics respond to “targeted violence,” a broad term that encompasses a variety of attacks in which an individual, pair, or small group attacks as many people as possible in a public place. Building upon Albert O. Hirschman’s The Rhetoric of Reaction and contemporary versions of classical stasis theory, the project develops an anatomy of arguments that people have made in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, the Boston Marathon bombing, and the Isla Vista attack (#YesAllWomen). The chapter on the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting advances the concept of a rhetorical void, which describes the space into which arguments about guns, mental illness, and school security disappear after conversations about them reach impasses. -

Citrus County

Project1:Layout 1 6/10/2014 1:13 PM Page 1 MLB: Rays, Yankees face in AL East battle /B1 THURSDAY TODAY C I T R U S C O U N T Y & next morning HIGH 90 Scattered LOW evening storms. 68 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JUNE 3, 2021 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community $1 VOL. 126 ISSUE 239 NEWS BRIEFS Citrus wins big with budget Citrus County COVID-19 cases County ‘got everything’ it According to the Flor- ida Department of Health, DeSantis signs state budget, 10 new positive cases asked for from state coffers were reported in Citrus MIKE WRIGHT projects is $3.9 million for County since the latest Staff writer sewers to remove septic vetoes $1.5B in spending update. tanks from about No new deaths were Gov. Ron De- 200 homes along Santis on Wednes- the Homosassa JIM TURNER “Once I sign this budget, we will be reported, for a total of News Service of Florida signing a budget that responsibly sup- 463. To date in the day vetoed River head spring $1.5 billion in just outside the ports our men and women in county, 11,411 people projects and not state wildlife park. TALLAHASSEE — While law enforcement, our have tested positive (in- one of them is in Senate Presi- pointing to an economic re- K-through-12 education stu- cluding 99 non- Citrus County. dent Wilton Simp- surgence amid the coronavi- dents and teachers, conserves residents). DeSantis signed son, R-Trilby, gave rus pandemic, Gov. Ron and protects our great envi- One new hospitaliza- a state budget that Ruthie direct praise to DeSantis on Wednesday used ronmental and natural re- tion was reported, for a includes $14.4 mil- Schlabach Commissioner his line-item veto power to sources throughout the state total of 742 hospitalized. -

Volk, Devils and Moral Panics in White South Africa, 1976 - 1993

The Devil’s Children: Volk, Devils and Moral Panics in White South Africa, 1976 - 1993 by Danielle Dunbar Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts (History) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Sandra Swart Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences March 2012 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2012 Copyright © 2012 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT There are moments in history where the threat of Satanism and the Devil have been prompted by, and in turn stimulated, social anxiety. This thesis considers particular moments of ‘satanic panic’ in South Africa as moral panics during which social boundaries were challenged, patrolled and renegotiated through public debate in the media. While the decade of the 1980s was marked by successive states of emergency and the deterioration of apartheid, it began and ended with widespread alarm that Satan was making a bid for the control of white South Africa. Half-truths, rumour and fantasy mobilised by interest groups fuelled public uproar over the satanic menace – a threat deemed the enemy of white South Africa.