Draft Debate on C-SPAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Monthly 2018 College Rankings

The Prison-to-School Pipeline 2018 COLLEGE RANKINGS What Can College Do For You? PLUS: The best—and worst— colleges for vocational certificates Which colleges encourage their students to vote? Why colleges should treat SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN students like numbers All Information Fixing higher education deserts herein is confidential and embargoed Everything you always wanted to know through Aug. 23, 2018 about higher education policy VOLUME 50 NUMBER 9/10 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 SOCIAL MOBILITY RESEARCH SERVICE Features NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES THE 2018 COLLEGE GUIDE *Public institution Introduction: A Different Kind of College Ranking 15 °For-profit institution by Kevin Carey America’s Best and Worst Colleges for%offederalwork-studyfunds Vocational Certificates 20 GraduationGrad rate rate rank performancePell graduationPell rank performance gap rankFirst-gen rank performancerankEarningsperformancerankNoNetpricerank publicationRepaymentrankPredictedrepaymentraterankResearch has expendituresBachelor’stoPhDrank everScience&engineeringPhDsrank rank rankedFacultyawardsrankFacultyinNationalAcademiesrank thePeaceCorpsrank schoolsROTC rank wherespentonservicerankMatchesAmeriCorpsservicegrants? millionsVotingengagementpoints of Americans 1 Harvard University (MA) 3 35 60 140 41 2seek 5 168 job310 skills.8 Until10 now.17 1 4 130 188 22 NO 4 2 Stanford University (CA) 7 128 107 146 55 11 by2 Paul16 48Glastris7 6 7 2 2 70 232 18 NO 1 3 MA Institute of Technology (MA) 16 234 177 64 48 7 17 8 89 13 2 10 3 3 270 17 276 NO 0 4 Princeton University (NJ) 1 119 100 100 23 20 Best3 30 &90 Worst67 Vocational5 40 6 5 Certificate117 106 203 ProgramsNO 1 Rankings 22 5 Yale University (CT) 4 138 28 121 49 22 America’s8 22 87 18Best3 Colleges39 7 9 for134 Student22 189 VotingNO 0 28 6 Duke University (NC) 9 202 19 156 218 18 Our26 15 first-of-its-kind183 6 12 list37 of9 the15 schools44 49doing215 theNO most3 to turn students into citizens. -

Overuse White Paper Formatted

White Paper Series Ranking and analysis of overuse in U.S. hospitals EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Overuse, which is also known as low-value care, is often defined as the provision of health care services for which the potential for harm exceeds the likely benefit to a patient. Overuse occurs in all healthcare settings, including hospitals. It exposes patients to preventable harm and wastes more than $100 billion each year. To date, no study has published the rate of overuse in specific U.S. hospitals. The Lown Institute Hospital Index is the first hospital ranking to grade individual hospitals by how well they avoid overuse. This white paper provides an analysis of the overuse of 13 low-value services in 3,282 U.S. hospitals using Medicare data. These 13 services include imaging tests, surgeries, and cardiovascular procedures, and have all been validated in previous studies of low-value care. Only instances of these services deemed inappropriate in the literature were counted as overuse. Hospitals that did not have the capacity to perform a specific low-value procedure did not have that service counted in their total grade. We find that overuse varies across hospitals by type, size, and location. Teaching hospitals, larger hospitals, urban hospitals, and for-profit hospitals on average ranked lower for avoiding overuse overall, compared to non-teaching, smaller, rural hospitals. However, these patterns were not always consistent across all low-value services. Safety net hospitals and small rural hospitals had higher rankings in avoiding overuse overall, but their scores differed by specific low-value service. For-profit hospitals consistently ranked lower than nonprofit hospitals for avoiding nearly every low-value service measured. -

The Seven Deadly Sins of Defense Spending

RESPONSIBLE DEFENSE SERIES JUNE 2013 The Seven Deadly Sins of Defense Spending By David Barno, Nora Bensahel, Jacob Stokes, Joel Smith and Katherine Kidder About the Report “The Seven Deadly Sins of Defense Spending” is part of an ongoing program called Responsible Defense at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS). The program examines how the United States should maximize its national security in an era of defense spending reductions. The program published its first report, “Hard Choices: Responsible Defense in an Age of Austerity,” in October 2011 and its second report, “Sustainable Pre-eminence: Reforming the U.S. Military in a Time of Strategic Change,” in May 2012. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the many talented people who contributed to this report. We thank Michèle Flournoy, Rudy DeLeon, Russell Rumbaugh, Todd Harrison and Travis Sharp for serving as reviewers. We also thank Matthew Leatherman and Howard Shatz for their thoughtful insights. We thank Shawn Brimley for providing editorial guidance throughout the process. We thank Phil Carter, Jason Combs, Kelley Sayler and April Labaro for their research contributions. We thank Liz Fontaine for imparting her creativity to the report’s design, and we thank Kay King and Will Shields for helping to spread our message. Their assistance does not imply any responsibility for the final product, which rests solely with the authors. A Note about Funding Some organizations that have business interests related to the defense industry support CNAS financially, but they pro- vided no direct support for the report. CNAS retains sole editorial control over its research and maintains a broad and diverse group of more than 100 funders including foundations, government agencies, corporations and private individuals. -

Speaker Directory

SPEAKER DIRECTORY NCRC NATIONAL ANNUAL CONFERENCE National Challenges, Local Solutions Rebuilding Homes, Lives and Communities April 13-16, 2011 Washington Court Hotel, Washington, DC 2 Aaron Dorfman, Executive Director, National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. Washington, DC Aaron Dorfman is executive director of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP), a research and advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C. NCRP works to ensure America’s grantmakers are responsive to the needs of those with the least wealth, opportunity and power. Before joining NCRP in 2007, Dorfman served for 15 years as a community organizer with two national organizing networks, spearheading grassroots campaigns to improve public education, expand public transportation for low-income residents and improve access to affordable housing. He holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Carleton College (where he studied under the late Senator Paul Wellstone) and a master’s degree in philanthropic studies from the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. Dorfman frequently speaks and writes about the importance of diversity in philanthropy, the benefits of foundation funding for advocacy and community organizing, and the need for greater accountability and transparency in the philanthropic sector. Senator Al Franken of Minnesota Alan Stuart “Al” Franken is the junior United States Senator from Minnesota. He is a member of the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, which affiliates with the national Democratic Party. Franken achieved note as a writer and performer for the television show Saturday Night Live from its inception in 1975 before moving to writing and acting in films and television shows. He then became a political commentator, author of five books and host of a nationally syndicated radio show on the Air America Radio network. -

Sample Draft Syllabus

CREATING THE AMERICAN METROPOLIS Loyola University Chicago Prof. Timothy J. Gilfoyle HIST 386, Sec. 204 511 Crown Fall 2018 (773) 508-2221 Tuesday, 2:30-5 p.m. E-mail: [email protected] Corboy Law Center, Room L08 Office Hours: MW, 9-10am, 11:30am-2pm http://luc.edu/history/people/facultyandstaffdirectory/timothyjgilfoyle.shtml "God made the country and man made the town." William Cowper, 1780 The United States was born in the country and moved to the city. This course examines the transformation of the United States from a simple agrarian and small-town society to a complex urban and suburban nation. Field trips and walking tours are a vital component of the class. Between 1850 and 1950, American urban communities were transformed from "horizontal" cities of row houses, tenements and factories to "vertical" cities of apartments and skyscrapers. From New York's Brooklyn Bridge to Chicago's Sears Tower to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge, the tower and the bridge epitomized American urbanism, and frequently America itself. Certain themes recur throughout the course of American urban and cultural history which will be focal points of this class: the interaction of private commerce with cultural change; the rise of distinctive working and middle classes; the creation and segregation of public and private spaces; 1 Sample Draft Syllabus the formation of new and distinctive urban subcultures organized by gender, work, race, religion, ethnicity, and sexuality; problems of health and housing resulting from congestion; and blatant social divisions among wealthy, poor, native-born, immigrant, and racial groups. More broadly, the course attempts to comprehend the American city within the changing questions of what it means to be an American. -

Etd Nlw8.Pdf

RED STATE, BLUE STATE, RED NEWS, BLUE NEWS A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture and Technology By Niki L. Woodard, B.A. Washington, DC April 28, 2006 RED STATE, BLUE STATE, RED NEWS, BLUE NEWS Niki L. Woodard, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Diana Owen, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The phrase “red state, blue state” has set off a debate as divisive as the social trend it describes. This thesis not only recognizes the disparity in defining red states and blue states, but aims to both separate and bridge these differences while introducing a powerful explanatory variable to the discussion – the news media, or what will be referred to as “red news, blue news.” Scholars have approached the topic of American polarization in a variety of ways, namely by looking at the public’s differences on salient issues, the public’s electoral voting habits and the differences among political elites. While the “culture war” and the “red state, blue state” maps of the 2000 and 2004 elections are illustrative of the general debate over political polarization, these theories have ignored the impact of both the mass media and the alternative media. Since the news media is where most Americans gather their information on world, national and local affairs, this seems an obvious place to look for polarizing messages. This research is organized by an investigation of the demand-side and supply- side of media polarization. -

Growth Management and the City

Growth Management and the City James A. Kushnert The way urban growth has been "managed," it is no surprise that Amer- ica's cities are dying.' During the last three decades, American urban growth policy was directed to suburban growth. Government encouraged exodus from the metropolis through: deep subsidies for highways, utilities, and open space; housing finance, particularly in the form of tax deductions for mortgage interest and real property taxes; and subsidized Veteran's Administration loans and Federal Housing Administration mortgage insurance.2 Leaving the city in search of suburban values, the affluent were followed by industry in search of greener locations, retail establishments that favor malls, and restaurants and entertainment outlets looking for secure locations. Thus, the economic base from which taxes are generated to fund public services was transferred to the suburbs. Despite notable, symbolic, and often exciting urban renewal projects, the suburban growth explosion left distinct patterns of systemic poverty in the cities. These patterns include: racial segregation, burgeoning crime, inadequate transit systems, decaying neighborhoods and housing stock, declining school systems, inadequate job training, high unemployment, rapid population expan- sion, minimal employment creation, and inadequate systems of public safety and health. America's urban streets and parks are often unsafe, and urban transit systems, bridges, water and sewer lines, and public buildings need extensive rebuilding. The situation requires both massive reallocation of the tax base and an escalation in taxing and spending on public works, human services, and job creation rivaling the scale of the New Deal. Without this radical alteration of America's urban policy, together with public safety initiatives reflecting a wartime mobilization, the American metropolis-indeed the nation-will be doomed to a declining quality of life that leads to eventual third world economic status. -

Instructor's Resource Manual on Social Problems

Instructor’s Resource Manual on Social Problems Third Edition Compiled and Edited by Lutz Kaelber University of Vermont and Walter Carroll Bridgewater State College AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION 1307 New York Avenue NW #700 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 383-9005 ASA Resource Materials for Teaching Copyright 2001 THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION Documents distributed by the American Sociological Association are not intended to represent the official position of the American Sociological Association. Instead, they constitute a medium by which colleagues may communicate with each other to improve the teaching of sociology. Table of Contents _____________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Essay: Teaching Social Problems ........................................................................................................1 Syllabi .........................................................................................................................................................................11 Walter F. Carroll, Bridgewater State College..............................................................................................................13 James A. Crone, Hanover College...............................................................................................................................16 Brenda Forster, Elmhurst College ...............................................................................................................................21 -

The “Regular Order”: a Perspective

The “Regular Order”: A Perspective November 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46597 SUMMARY R46597 The “Regular Order”: A Perspective November 6, 2020 Many contemporary lawmakers urge a return to “regular order” lawmaking. In general, the regular order refers to a traditional, committee-centered process of lawmaking, very Walter J. Oleszek much in evidence during most of the 20th century. Today, Congress has evolved to Senior Specialist in become largely a party-centered institution. Committees remain important, but they are American National less important than previously as “gatekeepers” to the floor. This development Government represents a fundamental “then and now” change in the power dynamics of Capitol Hill. Regular order is generally viewed as a systematic, step-by-step lawmaking process that emphasizes the role of committees: bill introduction and referral to committee; the conduct of committee hearings, markups, and reports on legislation; House and Senate floor consideration of committee-reported measures; and the creation of conference committees to resolve bicameral differences. Many Members and commentators view this sequential pattern as the ideal or “best practices” way to craft the nation’s laws. Regular order is a lawmaking process that promotes transparency, deliberation, and the wide participation of Members in policy formulation. Significant deviations from the textbook model of legislating—common in this party-centric period—might be called “irregular,” “nontraditional,” “unorthodox,” or “unconventional” lawmaking. The well- known “Schoolhouse Rock” model of legislating still occurs, but its prominence has declined compared with the rise of newer, party leadership-directed processes. Regular or irregular procedures can successfully be used to translate ideas into laws. -

The Missing Account of Progressive Corporate Criminal Law

Department of Criminology Working Paper No. 2017-5.0 The Missing Account of Progressive Corporate Criminal Law William S. Laufer This paper can be downloaded from the Penn Criminology Working Papers Collection: http://crim.upenn.edu THE MISSING ACCOUNT OF PROGRESSIVE CORPORATE CRIMINAL LAW William S. Laufer* INTRODUCTION This seems to be an ideal time to revisit the normative, doctrinal, and policy-laden foundations of the corporate criminal law. With renewed calls for a repeal of the most costly of corporate regulations and reforms, it is tempting to speculate about the future of corporate compliance and corporate criminal liability.1 A host of academics continue to worry about the many hard-to-quantify direct and collateral costs of corporate criminal liability.2 Regulators and legislators still question whether some financial institutions are too big to prosecute, take to trial, and convict.3 The general public fears *Julian Aresty Professor, Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics, Sociology, and Criminology; Director, Carol and Lawrence Zicklin Center; The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania (J.D., Ph.D.). Thanks to Vik Khanna, Jennifer Arlen, Sally Simpson, John Hagan, Eric Orts, Peter Conti-Brown, Mihailis E. Diamantis, Ron Levine, Steve Solow, Kip Schlegel, Eduardo Saad Diniz, and Dominik Brodowski for comments on earlier versions of this article. My appreciation to Serina Vash and The Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement at NYU Law School for their post of this Article. 1 See, e.g., Tom Fox, TRUMP AND -

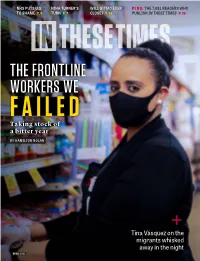

THE FRONTLINE WORKERS WE FAILED Taking Stock of a Bitter Year

NHS PUTS U.S. NINA TURNER’S WILL GITMO EVER PLUS: THE 7,081 READERS WHO TO SHAME P. 9 TURN P. 7 CLOSE? P. 56 PUBLISH IN THESE TIMES P. 28 THE FRONTLINE WORKERS WE FAILED Taking stock of a bitter year BY HAMILTON NOLAN + Tina Vásquez on the migrants whisked away in the night APRIL 2021 ADVERTISEMENT The Invention of the Year e world’s lightest and most portable mobility device 10” e Zinger folds to a mere 10 inches. Once in a lifetime, a product comes along that truly moves people. Introducing the future of battery-powered personal transportation... The Zinger. Throughout the ages, there have been many important folded it can be wheeled around like a suitcase and fits easily advances in mobility. Canes, walkers, rollators, and scooters into a backseat or trunk. Then, there are the steering levers. were created to help people with mobility issues get around They enable the Zinger to move forward, backward, turn and retain their independence. Lately, however, there haven’t on a dime and even pull right up to a table or desk. With its been any new improvements to these existing products or compact yet powerful motor it can go up to 6 miles an hour developments in this field. Until now. Recently, an innovative and its rechargeable battery can go up to 8 miles on a single design engineer who’s developed one of the world’s most charge. With its low center of gravity and inflatable tires it popular products created a completely new breakthrough... can handle rugged terrain and is virtually tip-proof. -

Daniel L Byman

PRINCETON PROBLEM-SOLVING WORKSHOP SERIES IN LAW AND SECURITY: A NEW LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR MILITARY CONTRACTORS? June 8, 2007 Sponsored by The Woodrow Wilson School of Public & International Affairs PARTICIPANT BIOGRAPHIES Douglas Brooks Douglas Brooks is President of The International Peace Operations Association (IPOA), a nongovernmental, nonprofit, nonpartisan association of service companies dedicated to improving international peacekeeping and stabilization efforts through greater privatization. He is a specialist on private sector capabilities and African security issues and has written extensively on the regulation and constructive utilization of the private sector for international stabilization, peacekeeping and humanitarian missions. Mr. Brooks has testified before the U.S. Congress, South African Parliament, appeared on numerous TV and radio programs including the BBC, CBS News, NBC News, Fox News, CNN International, National Public Radio, Voice of America, SABC in South Africa and the Lehrer News Hour. He has lectured at numerous universities and colleges, including Georgetown University, the South African Defense College, and the Inter-American Defense College at Ft. McNair. Mr. Brooks is originally from Indiana and has a BA in History from Indiana University, an MA in History from Baylor University, with doctoral studies at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Frank A. Camm, Jr. Dr. Camm is a senior economist with RAND and currently leads projects for the U.S. Air Force and Office of the Secretary of Defense. Dr. Camm has worked for RAND since 1976, except during 1983-85. At RAND, he has worked on many resource allocation and management issues. His defense-related work has addressed the development of manpower requirements; risk assessment and management; design of logistics supply chains; design of pricing, programming, budgeting, and other financial management processes; and sourcing of support services.