Reinventing Identity: Theatre of Roots and Ratan Thiyam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

AXC Instructions / ૂચના

AXC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Drama in Gov. Arts, Sci. & Commerce College, Class-2 Advertisement No. 69/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 20-08-2021 Question No 001 – 300 Publish Date 21-08-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 28-08-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 22-08-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ચનાૂ Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

THIRTY SECOND ANNUAL REPORT (1St April 2017 to 31St March 2018)

PONDICHERRY UNIVERSITY (A Central University) THIRTY SECOND ANNUAL REPORT (1st April 2017 to 31st March 2018) R. Venkataraman Nagar Kalapet Puducherry - 605 014 Published by Registrar, Pondichery University, Puducherry - 605 014, India Designed & Printed by Jay Ess Graphics, No.4, Second Cross, Navasakthi Nagar, VVP Nagar Arch Opp., Vazhudhavur Road, Kundupalayam, Puducherry - 605 009. e-mail : [email protected] Ph: 0413-4304606 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The University acknowledges the efforts ofProf. K. Rajan, Department of History, Prof. V. Mariappan, Department of Banking Technology and Prof. V.V. Ravi Kanth Kumar, Head, Department of Physics of Pondicherry University in consolidating and finalizing 32nd Annual Report of the University. The efforts of the Committee Members are appreciable and I thank them for their involvement and dedication. I also thank the Deans of Schools, Officers and Staff of University Administration for their support in the preparation of this Annual Report. Vice-Chancellor v VISITOR Hon’ble Shri. PRANAB MUKHERJEE President of India (upto 25.07.2017) Hon’ble Shri. RAM NATH KOVIND President of India (from 25.07.2017) CHANCELLOR Hon’ble Shri. MOHAMMAD HAMID ANSARI Vice-President of India (upto 11.08.2017) Hon’ble Shri. MUPPAVARAPU VENKAIAH NAIDU Vice-President of India (from 11.08.2017) CHIEF RECTOR Hon’ble Dr. KIRAN BEDI, IPS (Retd.) Lt. Governor of Puducherry VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. (Mrs.) ANISA BASHEER KHAN (officiating) (upto 29.11.2017 F.N.) Prof. GURMEET SINGH (from 29.11.2017) REGISTRAR Prof. M. RAMACHANDRAN (i/c) (upto 14.07.2017) Shri. B.R. BABU (from 14.07.2017 to 20.09.2017) Prof. -

The Lockdown to Contain the Coronavirus Outbreak Has Disrupted Supply Chains

JOURNALISM OF COURAGE SINCE 1932 The lockdown to contain the coronavirus outbreak has disrupted supply chains. One crucial chain is delivery of information and insight — news and analysis that is fair and accurate and reliably reported from across a nation in quarantine. A voice you can trust amid the clanging of alarm bells. Vajiram & Ravi and The Indian Express are proud to deliver the electronic version of this morning’s edition of The Indian Express to your Inbox. You may follow The Indian Express’s news and analysis through the day on indianexpress.com DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA JOURNALISM OF COURAGE THURSDAY, AUGUST 6, 2020, NEW DELHI, LATE CITY, 16 PAGES SINCE 1932 `6.00 (`8 PATNA &RAIPUR, `12 SRINAGAR) WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM Ram belongs to everyone; Ram’s niti is bhayabin hoye na preet Considering Covid,path of maryada Ram is within everyone (without fear thereisnolove) shown by Ram is even moreessential Modi marksNARENDRA MODI, PRIME MINISTERtheOF INDIA Mandir Aug 15, Aug 5: Opp responds PM draws by invoking parallel with Ram and unity, avoids BJP struggle for reference freedom MANOJCG NEWDELHI,AUGUST5 One year of Aug 5: AVANEESHMISHRA &MAULSHREESETH FORALL the faultlines that the AYODHYA,LUCKNOW, Ayodhya movement engen- J&K L-G exitsafter AUGUST 5 dered,today’s ceremonyof PrimeMinisterNarendraModi WITHa40-kgsilverbrick,asapling laying thefoundation stoneof talk of pollsand 4G and soil from across the nation, the Ramtemple prompted the Prime MinisterNarendraModi Opposition to frame their re- laid the foundation forthe Ram sponse in terms of national unity temple in Ayodhya Wednesday and divinity rather than the BJP. -

Takes Pleasure in Inviting You To

Nalanda Celebrates 50th Golden Jubilee Year 2015 takes pleasure in inviting you to NALANDA - BHARATA MUNI SAMMAN - 2014 SAMAROHA and Premier of Latest Dance Production PRITHIVEE AANANDINEE at: Ravindra Natya Mandir, Prabhadevi, Mumbai on: Sunday, the 18th January, 2015 at: 6.30 p.m. NALANDA'S BHARATA MUNI SAMMAN Dedicated to the preservation and propagation of Indian dance in particular and Indian culture in general from its founding in 1966 Nalanda Dance Research Centre has unswervingly trodden on its chosen path with single minded determination. Nalanda has always upheld the pricelessness of all that is India and her great ancient culture which consists of the various performing arts, visual arts, the mother of all languages Sanskrit and Sanskritic studies , the religio- philosophical thought and other co-related facets. Being a highly recognized research centre, Nalanda recognizes and appreciates all those endeavours that probe deep into the all encompassing cultural phenomena of this great country. Very naturally these endeavours come from most dedicated individuals who not only delve into this vast ocean that is Indian culture but also have the intellectual calibre to unravel, re-interpret and re-invent this knowledge and wisdom to conform with their own times. From 2011 Nalanda has initiated a process of honouring such individuals who have acquired iconic status. By honouring them Nalanda is honouring India on behalf of all Indians. Hence the annual NALANDA - BHARATA MUNI SAMMAN Recipients for 2014 in alphabetical order Sangeet Martand Pandit Jasraj's (Music) Shri. Mahesh Elkuchwar (Theatre) Rajkumar Singhajit Singh (Dance) Sangeet Martand Pandit Jasraj San g eet M ar t an d Pan d it Jas raj 's achievements are beyond compare more so because vocal music is the most intimate and direct medium according to India's musical treatise and tradition. -

In Search of Indianness: an Analytical and Performative Study of the Play ‘Raja’ by Rabindranath Tagore.”

A SYNOPSIS ON “IN SEARCH OF INDIANNESS: AN ANALYTICAL AND PERFORMATIVE STUDY OF THE PLAY ‘RAJA’ BY RABINDRANATH TAGORE.” SUBMITTED TO THE MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO UNIVERSITY OF BARODA FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE ARTS (DRAMATICS) BY DABHADE PRABHAKAR BHAUSAHEB AS A SELF GUIDE DEPARTMENT OF DRAMATICS FACULTY OF PERFORMING ARTS THE MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO UNIVERSITY OF BARODA VADODARA (GUJARAT) REGISTRATION NO: FOPA/48 DATED 21ST SEPTEMBER 2015 A SYNOPSIS ON “IN SEARCH OF INDIANNESS: AN ANALYTICAL AND PERFORMATIVE STUDY OF THE PLAY ‘RAJA’ BY RABINDRANATH TAGORE.” A wonderful allegorical play, Raja (published in 1911) or The King of Dark Chambers (published in 1914), the English version of the same play has been written way back in 1910 by the legendary poet, novelist and playwright Shri Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore’s theatrical imagination, political convictions, the idea of democracy and the nature of ideal governance portrayed in this play makes it challenging for any theatre person. Our country being the largest democratic country with the ongoing political ups and downs and the current need for ideal governance makes it more appealing for me to study the play ‘Raja’ rather thoroughly. After the Sanskrit classic theatre, Tagore’s work is considered as a bridge between the traditional and modern style of theatre. The search of indianness which was popular in those days when the play Raja was written also has a separate dimension. The connect between the nation as a whole and an individual and a Vis –a-Vis gets portrayed as the play echoes the very rhythm of unearthly and personal rousing of an individual in their eternal quest for truth and beauty. -

Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016

All Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016 Yea Sub Artist Name Field Category r Category Prabhakar Karekar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Padma Talwalkar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Koushik Aithal - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Yuva Puraskar 6 Yashasvi 201 Sirpotkar - Yuva Music Hindustani Vocal 6 Puraskar Arvind Mulgaonkar - 201 Music Hindustani Tabla Akademi 6 Awardee Yashwant 201 Vaishnav - Yuva Music Hindustani Tabla 6 Puraskar Arvind Parikh - 201 Music Hindustani Sitar Akademi Fellow 6 Abir hussain - 201 Music Hindustani Sarod Yuva Puraskar 6 Kala Ramnath - 201 Akademi Music Hindustani Violin 6 Awardee R. Vedavalli - 201 Music Carnatic Vocal Akademi Fellow 6 K. Omanakutty - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Neela Ramgopal - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Srikrishna Mohan & Ram Mohan 201 (Joint Award) Music Carnatic Vocal 6 (Trichur Brothers) - Yuva Puraskar Ashwin Anand - 201 Music Carnatic Veena Yuva Puraskar 6 Mysore M Manjunath - 201 Music Carnatic Violin Akademi 6 Awardee J. Vaidyanathan - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee Sai Giridhar - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee B Shree Sundar 201 Kumar - Yuva Music Carnatic Kanjeera 6 Puraskar Ningthoujam Nata Shyamchand 201 Other Major Music Sankirtana Singh - Akademi 6 Traditions of Music of Manipur Awardee Ahmed Hussain & Mohd. Hussain (Joint Award) 201 Other Major Sugam (Hussain Music 6 Traditions of Music Sangeet Brothers) - Akademi Awardee Ratnamala Prakash - 201 Other Major Sugam Music Akademi -

1 Sample Question Paper on Cinema Prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director

1 Sample question paper on cinema prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director. CRAFT Film School.Delhi.www.craftfilmschool.com: [email protected] Disclaimer about this sample paper ( 50+28 Objective questions ) by Naresh Sharma: 1. This is to clarify that I, Naresh Sharma, neither was nor is a part of any advisory body to FTII or SRFTI , the authoritative agencies to set up such question paper for JET-2018 entrance exam or any similar entrance exam. 2. As being a graduate of FTII, Pune, 1993, and having 12 years of Industry experience in my quiver as well the 12 years of personal experience of film academics, as being the founder of CRAFT FILM SCHOOL, this sample question-answers format has been prepared to give the aspiring students an idea of variety of questions which can be asked in the entrance test. 3. The sample question paper is mainly focused on cinema, not in exhaustive list but just a suggestive list. 4. As JET - 2018 doesn't have any specific syllabus, so any question related to General Knowledge/Current Affair can be asked. 5. Since Cinema has been an amalgamation of varied art forms, Entrance Test intends to check as follows; a) Information; and b) Analysis level of students. 6. This sample is targeted towards objective question-answers, which can form part of 20 marks. One need to jot down similar questions connected with Literature/ Panting Music/ Dance / Photography/ Fine arts etc. For any Query, one can write: [email protected] 2 Sample question paper on cinema prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director. -

Mahabharata in Visual and Performing Arts: Texts, Contexts and Images

Seminar on Text and Variation of the Mahabarata Session III: Mahabharata in visual and performing Arts: Texts, Contexts and Images MAHABHARATA AS REPRESENTED IN THE CLASSICAL AND CONTEMPORARY THEATRE OF KERALA Dr. K.G. Paulose Three ancient texts – Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata has moulded the mindset of Indians for centuries. Ramayana is the model for intra-domestic affairs, Mahabharata for interaction with society and Bhagavata for spiritual purity. Mahabharata, unlike the other two, is not permitted to be used for regular chanting for fear of creating quarrel in the household.1 Mahabharata presents man as he is where as the other two depicts a sophisticated and idealized levels of living. It is precisely because of this that theatre likes Mahabharata more than anything else. The influence of Mahabharata on theatre is tremendous. Bhasa and Kalidasa Mahabharata has been a veritable source for Sanskrit dramatists to develop their themes. Bhasa and Kalidasa were the earliest playwrights who were inspired by the great epic. Of the two, Bhasa revolted, often amending Vyasa by suitable substitutes and filling his silence with own interpretations. Kalidasa, on the other hand, often compromised to the epic narrative. Bhasa was sympathetic towards the characters who were marginalized, neglected and condemned - Karna, Duryodhana, Gatotkacha, etc.. He made them heroes. Krishna, Dharmaputra or even Arjuna became pale in their presence. In Pancharatra Bhasa goes to the extent of suggesting an alternative to Vyasa.2 Vyasa tells us that there is no alternative to bloodshed to solve the Kuru-Pandhava feud. It is an indirect approval for warfare. But Bhasa amends and corrects that there are alternatives, the way of negotiations, peaceful settlements. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT • First and Foremost I Want to Thank My Guide

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT • First and foremost I want to thank my Guide Prof. Mahesh Champaklal. It has been an honour to be his Ph.D. student. I appreciate all his contribution to make my ‘Ph.D. Research Work’ productive and stimulating. I am highly obliged and express my sincere gratitude to him. • I am also thankful to Faculty of Performing Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Shri Prabhakar Dabhade, Head - Department of Dramatics, Prof. Ajay Ashtaputre, Dean - Faculty of Performing Arts, Prof. R. G. Kothari, Director – Ph.D. Course Work and other authorities of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda for giving wonderful opportunity and co-operation without which this Research Work would not have been carried out. • I am extending my gratitude to my teachers Shri Rakesh Modi, Shri Darshan Purohit and colleagues Shri Trilok Mehra, Shri Vaibhav Bineewale and Shri Mehul Vyas for sharing their knowledge and experiences. I am also thankful to Prof. Parul Shah, Ex – Dean, Faculty of Performing Arts for their constant encouragement and support. I am thankful to the office staff of University and Faculty specially mentions Shri Hemant Gandhi, Shri Mahesh Parmar and Smt. Ami Shah for always supporting me as and when required. I also thank the two students Shri Shailesh Patel and Shri Amitavo Deb for their valuable assistance, in Graphic Work. • I am thankful to various libraries and staff members specially mention Smt. Preeti Bhatt and Smt. Kokila Parmar of Faculty of Performing Arts Library, H. M. Library, Oriental Institute Library, Sangeet Natak Akademi Library – New Delhi, NSD Library – New Delhi, N.C.P.A. -

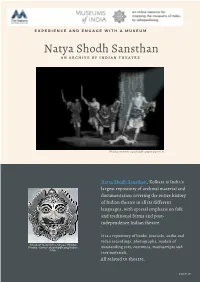

Natya Shodh Sansthan a N a R C H I V E O F I N D I a N T H E a T R E

E X P E R I E N C E A N D E N G A G E W I T H A M U S E U M Natya Shodh Sansthan A N A R C H I V E O F I N D I A N T H E A T R E Photo: www.natyashodh.org/index.htm Natya Shodh Sansthan, Kolkata is India's largest repository of archival material and documentation covering the entire history of Indian theatre in all its different languages, with special emphasis on folk and traditional forms and post- independence Indian theatre It is a repository of books, journals, audio and video recordings, photographs, models of Mask of Narsimha, Orissa, Photo: Photo: www.natyashodh.org/index. outstanding sets, costumes, manuscripts and htm rare materials. All related to theatre. PAGE 01 N a t y a S h o d h S a n s t h a n | E xperience & Engage with a Museum PAGE 02 P A G E 0 2 Natya Shodh Sansthan began its journey in July, 1981 as a theatre archive from 11, Pretoria Street, Kolkata, as a unit of Upchar Trust. The modest holding of a few journals, leaflets and diaries grew and the Sansthan built up its collection of priceless materials. Seminars, discussions and talks were regularly organized to record various aspects of histrionics on a pan-Indian level. With the new building established in 2019 (left hand side images), the Museum found its present address at EE 8, Sector 2, Salt Lake (Bidhan Nagar), Kolkata. -

THE THEME of BETRA YAL in INDIAN DRAMA in ENGLISH This Chapter Tries to Evaluate the Theme of Betrayal in Indian Drama

THE THEME OF BETRA YAL IN INDIAN DRAMA IN ENGLISH This chapter tries to evaluate the theme of betrayal in Indian Drama. For this purpose five plays written by Indian dramatists representing five different languages have been undertaken for study. Indian theatre could not promote Indian drama in the English language. The foremost factor responsible to harness the growth of Indian drama in English is the non availability of the living theatre. English drama written by Indian playwrights is neither excellent in quality nor greater in quantity. English, being a foreign language, was not intelligible to the masses and the playwrights found it difficult to write crisp, natural, lucid and graceful dialogues in English, which was not the language of their mental make up. Their dialogue was bound to be stilted and artificial. The English language, in India, is confined to the urban elite. R. K. Narayan ( 1999 :22 ) rightly puts it, thus : English has been with us for over a century, but it has remained the language of the intelligentsia, less than ten per cent of the population understands it. Indian dramatists cannot attain mastery to produce eloquent and elegant dialogues in English. At a national seminar on drama Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni (1984:163 ) goes to the extent of saying : Butcher them ( the Indo-AngUcan playwrights ) castrate them, and force them to write in their native Hindi or Urdu or whatever Indian languages their fathers and mothers used to speak. 260 The linguistic barrier created hurdles in the growth of Indian drama in English. Moreover, there was no English culture in India.