Pacaya-Samiria Reserve, Peru)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIOLOGICAL INVENTORIES REPORTS ARE PUBLISHED BY: Betty Moore Foundation./This Publication Has Been Funded in Part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

biological rapid inventories 12 Perú: Ampiyacu, Apayacu, Yaguas, Medio Putumayo Nigel Pitman, Richard Chase Smith, Corine Vriesendorp, Debra Moskovits, Renzo Piana, Guillermo Knell y/and Tyana Wachter, editores/editors ABRIL/APRIL 2004 Instituciones y Comunidades Participantes/ Participating Institutions and Communities The Field Museum Comunidades Nativas de los ríos Ampiyacu, Apayacu y Medio Putumayo/Indigenous Communities of the Ampiyacu, Apayacu and Medio Putumayo rivers FECONA FECONAFROPU Instituto del Bien Común Servicio Holandés de Cooperación al Desarrollo/ SNV Netherlands Development Organization Centro de Conservación, Investigación y Manejo de Áreas Naturales (CIMA-Cordillera Azul) Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos LOS INVENTARIOS BIOLÓGICOS RÁPIDOS SON PUBLICADOS POR / Esta publicación ha sido financiada en parte por Gordon and RAPID BIOLOGICAL INVENTORIES REPORTS ARE PUBLISHED BY: Betty Moore Foundation./This publication has been funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. THE FIELD MUSEUM Environmental and Conservation Programs Cita Sugerida/Suggested Citation: Pitman, N., R. C. Smith, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive C. Vriesendorp, D. Moskovits, R. Piana, G. Knell & T. Wachter Chicago, Illinois 60605-2496 USA (eds.). 2004. Perú: Ampiyacu, Apayacu, Yaguas, Medio Putumayo. T 312.665.7430, F 312.665.7433 Rapid Biological Inventories Report 12. Chicago, Illinois: www.fieldmuseum.org The Field Museum. Créditos Fotográficos/Photography credits: Editores/Editors: Nigel Pitman, Richard Chase Smith, Corine Vriesendorp, Debra Moskovits, Renzo Piana, Carátula/Cover: Un padre Bora con sus hijos atienden un taller en Guillermo Knell, Tyana Wachter Boras de Brillo Nuevo. Foto de Alvaro del Campo./A Bora father and his children attend a workshop in Boras de Brillo Nuevo. -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Molecular Phylogenetic Relationships and Generic Placement of Dryaderces Inframaculata Boulenger, 1882 (Anura: Hylidae)

70 (3): 357 – 366 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2020. 2020 Molecular phylogenetic relationships and generic placement of Dryaderces inframaculata Boulenger, 1882 (Anura: Hylidae) Diego A. Ortiz 1, 4, *, Leandro J.C.L. Moraes 2, 3, *, Dante Pavan 3 & Fernanda P. Werneck 2 1 College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia — 2 Coordenação de Biodiversidade, Programa de Coleções Científicas Biológicas, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA), Manaus, AM, Brazil — 3 Ecosfera Consultoria e Pes- quisa em Meio Ambiente Ltda., São Paulo, SP, Brazil — 4 Corresponding author; email: [email protected] — * These authors con- tributed equally to this work Submitted January 4, 2020. Accepted July 9, 2020. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/vertebrate-zoology on July 31, 2020. Published in print Q3/2020. Editor in charge: Raffael Ernst Abstract Dryaderces inframaculata Boulenger, 1882, is a rare species known only from a few specimens and localities in the southeastern Amazonia rainforest. It was originally described in the genus Hyla, after ~ 130 years transferred to Osteocephalus, and more recently to Dryaderces. These taxonomic changes were based solely on the similarity of morphological characters. Herein, we investigate the phylogenetic re lationships and generic placement of D. inframaculata using molecular data from a collected specimen from the middle Tapajós River region, state of Pará, Brazil. Two mitochondrial DNA fragments (16S and COI) were assessed among representative species in the sub family Lophiohylinae (Anura: Hylidae) to reconstruct phylogenetic trees under Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood criteria. Our results corroborate the monophyly of Dryaderces and the generic placement of D. inframaculata with high support. -

For Review Only

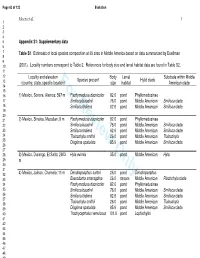

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Amazon Alive: a Decade of Discoveries 1999-2009

Amazon Alive! A decade of discovery 1999-2009 The Amazon is the planet’s largest rainforest and river basin. It supports countless thousands of species, as well as 30 million people. © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK © Brent Stirton / Getty Images The Amazon is the largest rainforest on Earth. It’s famed for its unrivalled biological diversity, with wildlife that includes jaguars, river dolphins, manatees, giant otters, capybaras, harpy eagles, anacondas and piranhas. The many unique habitats in this globally significant region conceal a wealth of hidden species, which scientists continue to discover at an incredible rate. Between 1999 and 2009, at least 1,200 new species of plants and vertebrates have been discovered in the Amazon biome (see page 6 for a map showing the extent of the region that this spans). The new species include 637 plants, 257 fish, 216 amphibians, 55 reptiles, 16 birds and 39 mammals. In addition, thousands of new invertebrate species have been uncovered. Owing to the sheer number of the latter, these are not covered in detail by this report. This report has tried to be comprehensive in its listing of new plants and vertebrates described from the Amazon biome in the last decade. But for the largest groups of life on Earth, such as invertebrates, such lists do not exist – so the number of new species presented here is no doubt an underestimate. Cover image: Ranitomeya benedicta, new poison frog species © Evan Twomey amazon alive! i a decade of discovery 1999-2009 1 Ahmed Djoghlaf, Executive Secretary, Foreword Convention on Biological Diversity The vital importance of the Amazon rainforest is very basic work on the natural history of the well known. -

Mannophryne Olmonae) Catherine G

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2014 A Not-So-Silent Spring: The mpI acts of Traffic Noise on Call Features of The loB ody Bay Poison Frog (Mannophryne olmonae) Catherine G. Clemmens The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Clemmens, Catherine G., "A Not-So-Silent Spring: The mpI acts of Traffico N ise on Call Features of The loodyB Bay Poison Frog (Mannophryne olmonae)" (2014). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 5783. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/5783 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2014 Catherine G. Clemmens A NOT-SO-SILENT SPRING: THE IMPACTS OF TRAFFIC NOISE ON CALL FEATURES OF THE BLOODY BAY POISON FROG (MANNOPHRYNE OLMONAE) DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY INDEPENDENT STUDY THESIS Catherine Grace Clemmens Adviser: Richard Lehtinen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Independent Study Thesis in Biology at the COLLEGE OF WOOSTER 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ABSTRACT II. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………...............…...........1 a. Behavioral Effects of Anthropogenic Noise……………………….........2 b. Effects of Anthropogenic Noise on Frog Vocalization………………....6 c. Why Should We Care? The Importance of Calling for Frogs..................8 d. Color as a Mode of Communication……………………………….…..11 e. Biology of the Bloody Bay Poison Frog (Mannophryne olmonae)…...13 III. -

Species Diversity and Conservation Status of Amphibians in Madre De Dios, Southern Peru

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 4(1):14-29 Submitted: 18 December 2007; Accepted: 4 August 2008 SPECIES DIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF AMPHIBIANS IN MADRE DE DIOS, SOUTHERN PERU 1,2 3 4,5 RUDOLF VON MAY , KAREN SIU-TING , JENNIFER M. JACOBS , MARGARITA MEDINA- 3 6 3,7 1 MÜLLER , GIUSEPPE GAGLIARDI , LILY O. RODRÍGUEZ , AND MAUREEN A. DONNELLY 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th Street, OE-167, Miami, Florida 33199, USA 2 Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Avenida Arenales 1256, Lima 11, Perú 4 Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, California 94132, USA 5 Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118, USA 6 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Zoología de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana, Pebas 5ta cuadra, Iquitos, Perú 7 Programa de Desarrollo Rural Sostenible, Cooperación Técnica Alemana – GTZ, Calle Diecisiete 355, Lima 27, Perú ABSTRACT.—This study focuses on amphibian species diversity in the lowland Amazonian rainforest of southern Peru, and on the importance of protected and non-protected areas for maintaining amphibian assemblages in this region. We compared species lists from nine sites in the Madre de Dios region, five of which are in nationally recognized protected areas and four are outside the country’s protected area system. Los Amigos, occurring outside the protected area system, is the most species-rich locality included in our comparison. -

Etar a Área De Distribuição Geográfica De Anfíbios Na Amazônia

Universidade Federal do Amapá Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade Tropical Mestrado e Doutorado UNIFAP / EMBRAPA-AP / IEPA / CI-Brasil YURI BRENO DA SILVA E SILVA COMO A EXPANSÃO DE HIDRELÉTRICAS, PERDA FLORESTAL E MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS AMEAÇAM A ÁREA DE DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE ANFÍBIOS NA AMAZÔNIA BRASILEIRA MACAPÁ, AP 2017 YURI BRENO DA SILVA E SILVA COMO A EXPANSÃO DE HIDRE LÉTRICAS, PERDA FLORESTAL E MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS AMEAÇAM A ÁREA DE DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE ANFÍBIOS NA AMAZÔNIA BRASILEIRA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade Tropical (PPGBIO) da Universidade Federal do Amapá, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Biodiversidade Tropical. Orientador: Dra. Fernanda Michalski Co-Orientador: Dr. Rafael Loyola MACAPÁ, AP 2017 YURI BRENO DA SILVA E SILVA COMO A EXPANSÃO DE HIDRELÉTRICAS, PERDA FLORESTAL E MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS AMEAÇAM A ÁREA DE DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE ANFÍBIOS NA AMAZÔNIA BRASILEIRA _________________________________________ Dra. Fernanda Michalski Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP) _________________________________________ Dr. Rafael Loyola Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) ____________________________________________ Alexandro Cezar Florentino Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP) ____________________________________________ Admilson Moreira Torres Instituto de Pesquisas Científicas e Tecnológicas do Estado do Amapá (IEPA) Aprovada em de de , Macapá, AP, Brasil À minha família, meus amigos, meu amor e ao meu pequeno Sebastião. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a CAPES pela conceção de uma bolsa durante os dois anos de mestrado, ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade Tropical (PPGBio) pelo apoio logístico durante a pesquisa realizada. Obrigado aos professores do PPGBio por todo o conhecimento compartilhado. Agradeço aos Doutores, membros da banca avaliadora, pelas críticas e contribuições construtivas ao trabalho. -

AMPHIBIANS of the RIOZINHO Do ANFRÍSIO Extractive Reserve,Pará

WEB VERSION PARÁ STATE, Eastern Amazon, BRAZIL AMPHIBIANS of the RIOZINHO do ANFRÍSIO Extractive Reserve, Pará 1 Flávio Bezerra Barros1,2; Luís Vicente2 and Henrique M. Pereira2 1Universidade Federal do Pará, Brazil; 2Centro de Biologia Ambiental, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal Photos by Flávio Bezerra Barros, except where indicated. Produced by Tyana Wachter, J. Philipp, & R. Foster, with support from Ellen Hyndman Fund & Andrew Mellon Foundation. © Flávio Bezerra Barros [[email protected]] Universidade Federal do Pará, Brazil; Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal © Environmental & Conservation Programs, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [[email protected]] [www.fmnh.org/animalguides/] Rapid Color Guide # 271 version 1 08/2010 1 Allophryne ruthveni 2 Allobates femoralis 3 Allobates sp. 4 Dendrophryniscus bokermanni ALLOPHRYNIDAE AROMOBATIDAE AROMOBATIDAE BUFONIDAE (carrying tadpoles) 5 Rhaebo guttatus 6 Rhinella castaneotica 7 Rhinella magnussoni 8 Rhinella gr. margaritifera BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE 9 Rhinella gr. margaritifera 10 Rhinella marina 11 Rhinella marina 12 Ceratophrys cornuta BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE CERATOPHRYIDAE (pair in amplexus) (pair in amplexus) 13 Proceratophrys concavitympanum 14 Adelphobates castaneoticus 15 Dendropsophus brevifrons 16 Dendropsophus leucophyllatus CYCLORAMPHIDAE DENDROBATIDAE HYLIDAE HYLIDAE photo: Pedro L.V. Peloso 17 Dendropsophus leucophyllatus 18 Dendropsophus leucophyllatus 19 Dendropsophus melanargyreus 20 Dendropsophus minusculus HYLIDAE HYLIDAE HYLIDAE HYLIDAE (yellow pattern) (giraffe pattern) WEB VERSION PARÁ STATE, Eastern Amazon, BRAZIL AMPHIBIANS of the RIOZINHO do ANFRÍSIO Extractive Reserve, Pará 2 Flávio Bezerra Barros1,2; Luís Vicente2 and Henrique M. Pereira2 1Universidade Federal do Pará, Brazil; 2Centro de Biologia Ambiental, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal Photos by Flávio Bezerra Barros, except where indicated. -

Systematics of Spinybacked Treefrogs (Hylidae

Zoologica Scripta Systematics of spiny-backed treefrogs (Hylidae: Osteocephalus): an Amazonian puzzle JULIAN FAIVOVICH,JOSE M. PADIAL,SANTIAGO CASTROVIEJO-FISHER,MARIANA M. LYRA,BIANCA V. M. BERNECK,CELIO F. B. HADDAD,PATRICIA P. IGLESIAS,PHILIPPE J. R. KOK,ROSS D. MACCULLOCH, MIGUEL T. RODRIGUES,VANESSA K. VERDADE,CLAUDIA P. TORRES GASTELLO,JUAN CARLOS CHAPARRO,PAULA H. VALDUJO,STEFFEN REICHLE,JIRI MORAVEC,VACLAV GVOZDIK,GIUSSEPE GAGLIARDI-URRUTIA,RAFFAEL ERNST,IGNACIO DELARIVA,DONALD BRUCE MEANS, ~ ALBERTINA P. LIMA,J.CELSA SENARIS &WARD C. WHEELER Submitted: 17 September 2012 Jungfer, K.-H., Faivovich, J., Padial, J. M., Castroviejo-Fisher, S., Lyra, M.L., Berneck, Accepted: 5 April 2013 B.V.M., Iglesias, P.P., Kok, P. J. R., MacCulloch, R. D., Rodrigues, M. T., Verdade, doi:10.1111/zsc.12015 V. K., Torres Gastello, C. P., Chaparro, J. C., Valdujo, P. H., Reichle, S., Moravec, J., Gvozdık, V., Gagliardi-Urrutia, G., Ernst, R., De la Riva, I., Means, D. B., Lima, A. P., Senaris,~ J. C., Wheeler, W. C., Haddad, C. F. B. (2013). Systematics of spiny-backed treefrogs (Hylidae: Osteocephalus): an Amazonian puzzle. —Zoologica Scripta, 00, 000–000. Spiny-backed tree frogs of the genus Osteocephalus are conspicuous components of the tropi- cal wet forests of the Amazon and the Guiana Shield. Here, we revise the phylogenetic rela- tionships of Osteocephalus and its sister group Tepuihyla, using up to 6134 bp of DNA sequences of nine mitochondrial and one nuclear gene for 338 specimens from eight coun- tries and 218 localities, representing 89% of the 28 currently recognized nominal species. Our phylogenetic analyses reveal (i) the paraphyly of Osteocephalus with respect to Tepuihyla, (ii) the placement of ‘Hyla’ warreni as sister to Tepuihyla, (iii) the non-monophyly of several currently recognized species within Osteocephalus and (iv) the presence of low (<1%) and overlapping genetic distances among phenotypically well-characterized nominal species (e.g. -

Zootaxa 2215: 37–54 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (Print Edition) Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (Online Edition)

Zootaxa 2215: 37–54 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of Osteocephalus (Anura: Hylidae) from Amazonian Bolivia: first evidence of tree frog breeding in fruit capsules of the Brazil nut tree JIŘÍ MORAVEC1,6, JAMES APARICIO2, MARCELO GUERRERO-REINHARD3, GONZALO CALDERÓN3, KARL-HEINZ JUNGFER4 & VÁCLAV GVOŽDÍK1,5 1Department of Zoology, National Museum, 115 79 Praha 1, Czech Republic. E-mail: [email protected] 2Museo Nacional de Historia Natural – Colección Boliviana de Fauna, Casilla 8706, La Paz, Bolivia 3Universidad Amazónica de Pando, Av. 9 de Febrero No. 001, Cobija, Bolivia. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 4Institute of Integrated Sciences, Department of Biology, University of Koblenz-Landau, Universitätsstr. 1, 56070 Koblenz, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 5Department of Vertebrate Evolutionary Biology and Genetics, Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 277 21 Liběchov, Czech Republic. E-mail: [email protected] 6Corresponding author Abstract A new species of Osteocephalus is described from lowland Amazonia of the Departamento Pando, northern Bolivia. The new species is most similar to Osteocephalus planiceps but differs by its smaller size (SVL 47.8–51.3 mm in males, 47.7–63.3 mm in females), absence of vocal slits, lack of sexual dimorphism in dorsal tubercles, single distal subarticular tubercle on the fourth finger, absence of dark spots on flanks, and by bicoloured iris with fine dark reticulate to radiate lines. The new species inhabits terra firme rainforest, breeds in water-filled fruit capsules of the Brazil nut tree and has oophagous tadpoles. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6 * x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE PRIVATION AND UNCERTAINTY IN THE SMALL NURSERY OF PERUVIAN LAUGHING FROGS: LARVAL ECOLOGY SHAPES THE PARENTAL MATING SYSTEM A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy BY LYNN HAUGEN Norman, Oklahoma 2002 UMI Number: 3054051 UMI UMI Microform 3054051 Copyright 2002 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company.