Biopsychological Investigation of Hedonic Processes in Individuals Susceptible to Overeating: Role of Liking and Wanting in Trait Binge Eating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Address the Risk of Reprisals in Complaint Management

GUIDE FOR INDEPENDENT ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS ON MEASURES TO ADDRESS THE RISK OF REPRISALS IN COMPLAINT MANAGEMENT A Practical Toolkit Guide for Independent Accountability Mechanisms on Measures to Address the Risk of Reprisals in Complaint Management: A Practical Toolkit Copyright © 2019 Inter-American Development Bank. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons IGO 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (CC-IGO BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ igo/legalcode) and may be reproduced with attribution to the IDB and for any non- commercial purpose. No derivative work is allowed. Any dispute related to the use of the works of the IDB that cannot be settled amicably shall be submitted to arbitration pursuant to the UNCITRAL rules. The use of the IDB’s name for any purpose other than for attribution, and the use of IDB’s logo shall be subject to a separate written license agreement between the IDB and the user and is not authorized as part of this CC-IGO license. Note that link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the license. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Inter-American Development Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent. Author: Tove Holmström Commissioned by the Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism (IDBG) Editors: Anne Perrault (UNDP-SECU), Ana María Mondragón, Pedro León and Victoria Márquez Mees (IDBG-MICI) Design: Alejandro Scaff Cover photo: Pexels Back cover photo: MICI January 2019 Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism FOREWORD The idea of producing a toolkit that would assist independent accountability mechanisms (IAMs) address the risk of reprisals within the context of their complaint management process came as a result of discussions with members of the IAM Working Group on Retaliation. -

Serving America

Proven leadership, a strong work ethic, discipline, teamwork—traits often used to describe those in our nation’s military. They are the same traits also associated with those who earn an M.B.A. The Simon Graduate School of Business has recognized this in its long tradition of accepting students with military backgrounds. As far back as the early 1970’s, instructors in the University of Rochester’s Naval R.O.T.C. program have taught naval science courses and attended Simon on Fridays through the Executive M.B.A. Program. During that time, Simon also offered an M.S. program in Systems Analysis, overseen by Ronald W. Hansen, senior associate dean for faculty and research, that enrolled and graduated approximately 75 mid-career military officers. Over the years, many Simon international students have performed military service in their home countries as well. Over the past two years, under Dean Mark Zupan’s leadership, the School has accelerated efforts to actively recruit M.B.A. candidates with military experience—either on orders from the military while on active duty or following several years of military service. “Since its inception, the Simon School has sought to attract the best and brightest candidates to attend its programs,” says Zupan. “Aside from today’s political climate, we continue to believe that the skills and traits inherent in current or former members of the military mirror those necessary for earning a graduate business degree and being successful.” Zupan ap- pointed Daniel H. Struble, retired Navy captain and former head of the University’s N.R.O.T.C. -

Category of Supplement Types of Claims Examples of Claims (2007) Enforceme Nt? •Germs Are Everywhere

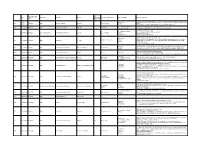

Referred to Gov Date of Decision Type Challenger Advertiser Product Agency for Category of Supplement Types of Claims Examples of Claims (2007) Enforceme nt? •Germs are everywhere. Take Airborne to boost your immune system, fight viruses and help you stay Case •Performance 4648 3/26/2007 NAD Airborne Health Inc. Airborne Immune Health healthy. Report •Implied •Take Airborne. The immune boosting tablet that helps your body fight germs. •Clinically Proven/Shown •CH-Alpha is scientifically proven to promote joint health. 4652 Case Report 4/10/2007 NAD Gelita Health Products CH-Alpha Joint Health •Preventative Health •After just two to three months, you will regain the freedom of flexibility. •94% faster recovery [from colds] •Clinically Proven/Shown •Increased immune system resistance by 312% 4653 Case Report 4/10/2007 Proctor and Gamble Iovate Health Sciences Inc. Cold MD Immune Health •Speed •Clinically Proven results •Comparative •Doctor formulated and approved •Chromax helps your insulin function at its best. •Performance •It's an advanced, highly absorbable form of chromium that provides your body with the chromium it Blood Sugar Health •Insulin 4547 Compliance 4/11/2007 NAD Nutrition 21 Chromax needs to help promote healthy blood sugar, fight carbohydrate cravings and support your overall •Implied cardiovascular health. •Essential for optimum insulin health. •Exclusivity •One-A-Day Women's Multi-Vitamin is the only complete multi-vitamin with more calcium for strong 4672 Case Report 5/1/2007 NAD Bayer Consumer Healthcare One-A-Day Women's Multi-Vitamin •Implied bones, and now more vitamin D, which emerging research suggests may support breast cancer. -

2020 Corporate Responsibility Report Table of Contents

2020 Corporate Responsibility Report Table of Contents OVERVIEW 3 PEOPLE & COMMUNITIES 32 A Letter from our Chairman & CEO and CSO 3 Employee Health & Safety 33 About This Report Our Company 4 Employee Engagement & Development 35 Keurig Dr Pepper (KDP) has reported on Key Highlights 5 Diversity & Inclusion 37 its corporate responsibility program since Our Corporate Responsibility Strategy 6 Community Engagement 39 the Company was formed in July 2018. This progress report focuses on the goals, Stakeholder Engagement & Materiality 8 programs and initiatives that encompass our key corporate responsibility efforts for Goals & Progress 9 GOVERNANCE 41 2020. In addition, we have created a Data Responding to COVID-19 10 Summary, which can be found at the end Board Management & Oversight 42 of this report. Unless otherwise noted, this report covers data and activities for calendar Ethics & Compliance 43 year 2020 from KDP’s wholly owned ENVIRONMENT 11 operations, which are primarily located in the Human Rights 44 U.S., Canada and Mexico. The content covers Product Design & Circular Economy 12 the parts of our business in which we have operational control and does not include Resource Use & Conservation 15 APPENDIX joint ventures, franchised or outsourced 45 operations, except where noted. Selected Water Efficiency & Stewardship 16 Data Summary 45 data and information on our global supply Climate, Emissions & Energy 18 chain activities are also included. Goal Methodology 52 We have expanded the scope of independent Stakeholder Engagement 58 verification for 2020 to include more SUPPLY CHAIN 20 environmental metrics, assurance on the Reporting Framework Indices (GRI, SASB, TCFD) 61 Environmental and Supply Chain sections Responsible Sourcing 21 of the report, and assurance for applicable Sustainability Accounting Standards Improving Livelihoods 23 Board (SASB) standards. -

Substance Abuseabuse

SubstanceSubstance AbuseAbuse ForFor FosterFoster Parents,Parents, CaregiversCaregivers && TeachersTeachers TeenTeen TrendsTrends-- WhatWhat toto KnowKnow 1: THEY’RE STRESSED. Today’s teens are stressed out. Factors include school work (they have more than ever. The Internet speeds things up but that just means that they're given even more work), college pressures, advanced placement courses in high school, and being overscheduled. The (stereotypical) Gen X slackers they are not. 2: THEY’RE HYPER-SEXUALIZED. Things like mini-skirts in schools, guys taking Creatine to get bulked up for sports, Real World MTV hook ups with young adults sleeping with strangers in each episode, online dating sites and Internet porn... This stuff is in their face every day. Teens are trying to act older, while older people are trying to act younger. So you've got kids trying to be adults, and adults (like Baby Boomers in particular) trying to be kids. It makes for a weird dynamic – and can confuse the teen as to who's the role model? Surprisingly, kids are more mature about things than you'd expect. 3: FRIENDS ARE THE NEW FAMILY. You say, “a person's friends have been important to every generation." But this cohort seems to equally value their circle of friends as their secondary family. They are far more group oriented than Gen Xers. Even if you think about Sesame Street, the show Xers grew up with ("We're all unique and different") compared to Barney, the show Gen Y grew up with ("Everybody is equal -- We're all the same.") Gen Y tends to be more conformist than Xers and Boomers were in their youth. -

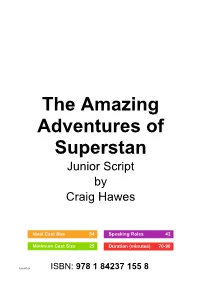

The Amazing Adventures of Superstan Junior Script By

The Amazing Adventures of Superstan Junior Script by Craig Hawes Ideal Cast Size 54 Speaking Roles 42 Minimum Cast Size 25 Duration (minutes) 70-90 3/280917/28 ISBN: 978 1 84237 155 8 Published by Musicline Publications P.O. Box 15632 Tamworth Staffordshire B78 2DP 01827 281 431 www.musiclinedirect.com Licences are always required when published musicals are performed. Licences for musicals are only available from the publishers of those musicals. There is no other source. All our Performing, Copying & Video Licences are valid for one year from the date of issue. If you are recycling a previously performed musical, NEW LICENCES MUST BE PURCHASED to comply with Copyright law required by mandatory contractual obligations to the composer. Prices of Licences and Order Form can be found on our website: www.musiclinedirect.com The Amazing Adventures of Superstan – Script 1 CONTENTS Cast List ............................................................................................................................... 4 Suggested Cast List For 54 Actors ................................................................................... 5 Suggested Cast List For 25 Actors ................................................................................... 7 Characters In Each Scene .................................................................................................. 9 List Of Properties .............................................................................................................. 10 Production Notes ............................................................................................................. -

Hey-Whipple-Squeeze-This-A-Guide

Hey,Whipple, Squeeze This A Guide to Creating Great Ads Third Edition LUKE SULLIVAN John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hey,Whipple, Squeeze This Adweek Books address the challenges and opportunities of the marketing and advertising industries, written by leaders in the business. We hope readers will find these books as helpful and inspiring as Adweek, Brandweek, and Mediaweek magazines. Great Books from the Adweek Series Include: Disruption: Overturning Conventions and Shaking Up the Marketplace, by Jean-Marie Dru Truth, Lies and Advertising: The Art of Account Planning, by Jon Steel Perfect Pitch: The Art of Selling Ideas and Winning New Business, by Jon Steel Eating the Big Fish: How Challenger Brands Can Compete Against Brand Leaders, 2nd Edition, by Adam Morgan Life after the 30-Second Spot: Energize Your Brand With a Bold Mix of Alternatives to Traditional Advertising, by Joseph Jaffe Pick Me!: Breaking Into Advertising, and Staying There, by Janet Kestin and Nancy Vonk Hey, Whipple, Squeeze This: A Guide to Creating Great Advertising, 3rd Edition, by Luke Sullivan Hey,Whipple, Squeeze This A Guide to Creating Great Ads Third Edition LUKE SULLIVAN John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Copyright © 2008 by Luke Sullivan All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. -

Search & Seizure Law in Missouri

Search & Seizure Law in Missouri State & Federal Law H. Morley Swingle Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Boone County, Missouri 705 E. Walnut Street Columbia, MO 65201 January 2020 Edition Contents Part One - Introduction I. Constitutional Authority .................................................................................................. 10 II. Checklist for Busy Practitioner ..................................................................................... 10 III. Fourth Amendment Applicability Examples ................................................................... 11 1. Non-coverage of Place (Other Country)..................................... 11 2. Open Fields vs. Curtilage) ..................................................................... 11 3. Thermal Imaging Device (Heat Leaving Premises; Bodies Moving Inside Home) ............................................................... 13 4. Abandoned Property ................................................................................ 13 5. Information in Law Enforcement Database .............................................. 15 6. Government v. Private Action .................................................................. 15 7. No Expectation of Privacy - Key in Lock ................................................ 17 8. Information From Utility & Phone Companies ......................................... 17 Use of Electricity ............................................................................. 17 Cell Tower Site Location Information ............................................. -

Buying for Workplace Equality 2016 a Few Ways You Can Help Fight Dear for Equality Every Day: Friends,Take Action for Equality

5 A Guide To Companies, Products And Services That Support Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual And Transgender Workplace Inclusion BUYING FOR WORKPLACE EQUALITY 2016 A FEW WAYS YOU CAN HELP FIGHT DEAR FOR EQUALITY EVERY DAY: FRIENDS,TAKE ACTION FOR EQUALITY Share this information with your friends, family and co-workers. Help them become supporters of workplace equality by factoring the information from this guide into 1 purchasing decisions. Advocate for equality in the work- place. If your company isn’t on this list or you think it can do better, go to www.hrc.org/cei to find out how to 2 engage your employer. Get active about equality. Sign up for newsletters and Action Alerts at 3 www.hrc.org/workplace. 1 The maxim that the customer is always right has never been truer in today’s hyper- connected global market. Consumers can publicly praise or criticize businesses they patronize with the click of a button and influence friends’ and strangers’ purchasing behaviors. Businesses cannot afford to ignore the increasingly savvy and engaged consumer. As consumers, you know that you have a choice. And with this Buying for Workplace Equality guide, providing the most accurate review of a business’s workplace policies toward lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender employees, we hope that you feel empowered to make those purchasing decisions that are most important to you. This year’s guide includes results from the 2016 Corporate Equality Index, which features 407 businesses that scored a perfect 100 percent. All scores are based on the same set of criteria, rating 40 LGBT-related policies, benefits and corporate practices among the largest US businesses. -

Sports Nutrition Guidebook

Sports Nutrition Guidebook FOURTH EDITION Nancy Clark, MS, RD, CSSD Healthworks Fitness Center Chestnut Hill, MA Human Kinetics Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Nancy, 1951- [Sports nutrition guidebook] Nancy Clark’s sports nutrition guidebook / Nancy Clark. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-7360-7415-5 (soft cover) ISBN-10: 0-7360-7415-5 (soft cover) 1. Athletes--Nutrition. I. Title. II. Title: Sports nutrition guidebook. TX361.A8C54 2008 613.2'024--dc22 2007051946 ISBN-10: 0-7360-7415-5 (print) ISBN-13: 978-0-7360-7415-5 (print) ISBN-10: 0-7360-8086-4 (Adobe PDF) ISBN-13: 978-0-7360-8086-6 (Adobe PDF) ISBN-10: 0-7360-7877-0 (Mobipocket) ISBN-13: 978-0-7360-7877-1 (Mobipocket) ISBN-10: 0-7360-7878-9 (Kindle) ISBN-13: 978-0-7360-7878-8 (Kindle) Copyright © 2008, 2003, 1997, 1990 by Nancy Clark All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information storage and retrieval system, is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. This publication is written and published to provide accurate and authoritative information relevant to the subject matter presented. It is published and sold with the understanding that the author and publisher are not engaged in rendering legal, medical, or other professional services by reason of their authorship or publication of this work. If medical or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. -

Robbinswold Camp Song Book

Aardvark in the Park The Airplane Song There’s a large dark aardvark in the park Open your song book to page 13. They say he’s missing from the zoo If I had the wings of an airplane, airplane The police are looking high and low, Up in the sky I would fly, would fly They haven’t seen him, have you? If I had the wings of an airplane, airplane Oh I’ll tell you the reason, I’d fly till the day I would die, would die Because it’s aardvark mating season! When an aardvark makes a date Chorus: Ooh la la, ooh la la, ooh la la, repeat You know he slips right through that old zoo gate Ooh la la, ooh la la, ooh la la, again So if you see two aardvarks playing in the park Ooh la la, ooh la la, ooh la la, once more Don’t upset their apple cart. Ooh la la, ooh la la, la, the end Why? Close your song book You are not a spy, you’re not the FBI, And you should never break an aardvark’s heart! Alive, Awake, Alert, Enthusiastic I’m alive, awake, alert, enthusiastic (2x) I’m alive, awake, alert Adams Family Grace I’m alert, awake, alive I’m alive, awake, alert, enthusiastic *Duh-nuh-nuh-nuh (snap, snap) Duh-nuh-nuh-nuh (snap, snap) Duh-nuh-nuh-nuh, duh-nuh-nuh-nuh, Alice the Camel Duh-nuh-nuh-nuh (snap, snap)* Alice the camel has 10 humps (3x) We thank the earth for giving So go, Alice, go! This food we need for living So bless us while we eat it (Continue on down to…) Because we really need it (The Girl Scout family) * Alice the camel has no humps (3x) Cause Alice is a horse! Animal Song Alligator Animals are lots of fun *Alligator, alligator They’re big and round and hairy Can be your friend, can be your friend, can be your friend, Some have teeth and some have claws too* And some are rather scary. -

WNYW, New York, NY This Report Covers the Time Period November 1, 2005 to October 31, 2007 (Except Where Otherwise Specifically Noted)

1 WNYW, New York, NY This report covers the time period November 1, 2005 to October 31, 2007 (except where otherwise specifically noted). I. PROGRAMMING: a. Local Newscasts: WNYW airs 38 hours of local news each week, at the following times: Monday – Friday: 5 a.m. – 9 a.m. Monday – Friday: 11 a.m. – 11:30 a.m. Monday – Friday: 5 p.m. – 6:30 p.m. Monday – Friday: 10:00 p.m. – 11:00 p.m. Saturday – Sunday: 6 pm. – 6:30 p.m. Saturday – Sunday: 10 p.m. – 11 p.m. b. Breaking News Stories: WNYW broke into and/or preempted regularly scheduled programming on numerous occasions during the period covered by this report in order to bring its viewers breaking news or disaster information. This coverage included extended reporting on severe weather warnings, amber alerts, school closings, and other emergencies. A comprehensive list of cut‐ins and crawls is attached as Exhibit 1. c. Local News Stories: Provided below are examples of local news stories aired on WNYW during the report period: • Health: The Union representing more than a thousand home health workers is going on strike. They're demanding a salary increase to $10 an hour by 2007 (12/7/05). • Education: Early grade enrollment: Dozens of parents camp out in front of a prestigious Brooklyn elementary school so their children can qualify for early admission (3/12/07). • Community: Triple fatal fire: We now know the cause of a fire in Brooklyn that killed three children. Firefighters say one of the kids was playing with butane lighter.