Final Draft.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veggie Planet 2017

The economy: Our enemy? Big corporations: Friend, enemy or partner of the vegan movement? Renato Pichler, Swissveg-President Kurt Schmidinger, Founder „Future Food“ Talk on Nov. 2017 for CARE in Vienna 1 Who we are Renato Pichler • Since 24 years vegan • Founder and CEO of the V-label-project (since 1996) • Since 1993 I have been working full-time for the largest Swiss vegetarian and vegan organisation: Swissveg • I am also in the board of the European Vegetarian Union and Das Tier + Wir (animal ethics education in schools) Kurt Schmidinger • Master in geophysics and doctor in food science also software-engineer and animal rights activist • Founder and CEO of „Future Food“ • Scientific board member of Albert-Schweitzer-Stiftung, VEBU, GFI, etc. 2 What should we buy? When we buy a product: We support the producer and the merchant. If we buy meat, we support the meat-industry. If we buy a vegan product, we support the vegan industry. 3 What should we buy? Consequences of the success of the vegan movement: ● even meat-producers have a vegan product-range ● big corporations are interested in the vegan-market Should a vegan buy a vegan product from a meat-producer of a big corporation? 4 Role Play Kurt Opponinger: I’m against it! Kurt Proponinger: I support every vegan product! ? 5 Defining the goals 1) Simplifying life for vegans 2) Reduce meat consumption – increase consumption of vegan products 3) Establishing vegan as the norm in society 4) Support the small pure vegan-shops/producers Depending on the main goal, the optimal procedure can change. -

Out of Town Walk 3 out of Town Walk This Walk Takes You to Some Significant Duration Establishments and Resting Places 2-3 Hours Connected with the Rowntree Family

OUT OF TOWN ROWNTREE WALK FROM CHOCOLATE COMES CHANGE 1 | Out of Town walk 3 Out of Town Walk This walk takes you to some significant Duration establishments and resting places 2-3 Hours connected with the Rowntree family. Begin at Walmgate Bar with the walls Calories and city centre behind you. Turn right (in KitKat fingers) onto Paragon Street and shortly after 5 fingers turn left onto Barbican Road. At the crossroads turn left onto Heslington Road and follow this up the hill until you reach the entrance to The Retreat. The sites on this walk are rather far flung, so get your walking shoes on! The Retreat The Retreat, still today a Mental Health Care Provider, was opened in 1796 by Quaker William Tuke to provide a place where the mentally ill (initially Quakers only) could be treated with respect and dignity. This happened after the tragic death of Hannah Mills in York Lunatic Asylum (see Clifton walk). The Retreat was groundbreaking. Tuke tried to create a 'community' rather than an asylum, where there were no doctors, only 'attendants' who lived with the patients, encouraging a familial atmosphere. The 19th century saw the emergence of the new discipline of psychiatry, and the 'moral treatment' practised at The Retreat was influential on the developing treatment of mental illness. Out of Town walk | 2 Look out for Many of the buildings date from the 18th and 19th centuries and include work of several of the foremost architects of the city. The architect Walter Brierley added extensions, including the adjacent building Lamel Beeches, originally the home of the superintendent of the hospital. -

Biopsychological Investigation of Hedonic Processes in Individuals Susceptible to Overeating: Role of Liking and Wanting in Trait Binge Eating

- 1 - Biopsychological Investigation of Hedonic Processes in Individuals Susceptible to Overeating: Role of Liking and Wanting in Trait Binge Eating Michelle Dalton Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute of Psychological Sciences July 2013 - 2 - The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own, except where work which has formed part of jointly authored publications has been included. The contribution of the candidate and the other authors to this work has been explicitly indicated below. The candidate confirms that appropriate credit has been given within the thesis where reference has been made to the work of others. Chapter 2 of this thesis was based in part on the jointly-authored publication: Dalton, M., King, N.A., & Finlayson, G., (2013) Appetite, Satiety and Food Reward in Obese Subjects: A Phenotypic Approach, Current Nutrition Reports, 1-9. Chapter 7 of this thesis was based in part on the jointly-authored publication: Dalton, M., Blundell, J. & Finlayson, G. (2013) Effect of BMI and binge eating on food reward and energy intake: further evidence for a binge eating subtype of obesity. Obesity Facts, 6; 348-359. Chapter 8 of this thesis was based in part on the jointly-authored publication: Dalton, M., Blundell, J. & Finlayson, G. (2013) Examination of obese binge-eating subtypes on reward, food choice and energy intake under laboratory and free-living conditions. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 757. The candidate confirms that her contribution was primarily intellectual and she took a primary role in the production of the substance and writing of each of the above. -

Address the Risk of Reprisals in Complaint Management

GUIDE FOR INDEPENDENT ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS ON MEASURES TO ADDRESS THE RISK OF REPRISALS IN COMPLAINT MANAGEMENT A Practical Toolkit Guide for Independent Accountability Mechanisms on Measures to Address the Risk of Reprisals in Complaint Management: A Practical Toolkit Copyright © 2019 Inter-American Development Bank. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons IGO 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (CC-IGO BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ igo/legalcode) and may be reproduced with attribution to the IDB and for any non- commercial purpose. No derivative work is allowed. Any dispute related to the use of the works of the IDB that cannot be settled amicably shall be submitted to arbitration pursuant to the UNCITRAL rules. The use of the IDB’s name for any purpose other than for attribution, and the use of IDB’s logo shall be subject to a separate written license agreement between the IDB and the user and is not authorized as part of this CC-IGO license. Note that link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the license. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Inter-American Development Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent. Author: Tove Holmström Commissioned by the Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism (IDBG) Editors: Anne Perrault (UNDP-SECU), Ana María Mondragón, Pedro León and Victoria Márquez Mees (IDBG-MICI) Design: Alejandro Scaff Cover photo: Pexels Back cover photo: MICI January 2019 Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism FOREWORD The idea of producing a toolkit that would assist independent accountability mechanisms (IAMs) address the risk of reprisals within the context of their complaint management process came as a result of discussions with members of the IAM Working Group on Retaliation. -

Serving America

Proven leadership, a strong work ethic, discipline, teamwork—traits often used to describe those in our nation’s military. They are the same traits also associated with those who earn an M.B.A. The Simon Graduate School of Business has recognized this in its long tradition of accepting students with military backgrounds. As far back as the early 1970’s, instructors in the University of Rochester’s Naval R.O.T.C. program have taught naval science courses and attended Simon on Fridays through the Executive M.B.A. Program. During that time, Simon also offered an M.S. program in Systems Analysis, overseen by Ronald W. Hansen, senior associate dean for faculty and research, that enrolled and graduated approximately 75 mid-career military officers. Over the years, many Simon international students have performed military service in their home countries as well. Over the past two years, under Dean Mark Zupan’s leadership, the School has accelerated efforts to actively recruit M.B.A. candidates with military experience—either on orders from the military while on active duty or following several years of military service. “Since its inception, the Simon School has sought to attract the best and brightest candidates to attend its programs,” says Zupan. “Aside from today’s political climate, we continue to believe that the skills and traits inherent in current or former members of the military mirror those necessary for earning a graduate business degree and being successful.” Zupan ap- pointed Daniel H. Struble, retired Navy captain and former head of the University’s N.R.O.T.C. -

Nestlé's Winning Formula for Brand Management

Feature By Véronique Musson Nestlé’s winning formula for brand management ‘Enormous’ hardly begins to describe the trademark that develop products worldwide and are managed from our portfolio of the world’s largest food and drink company headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland or St Louis in the United States,” he explains. So eight trademark advisers, also based in Vevey, advise one – and the workload involved in managing it. But when or more strategic business units on the protection of strategic it comes to finding the best solutions to protect these trademarks, designs and copyrights, while one adviser based in St very valuable assets, Nestlé has found that what works Louis advises the petcare strategic business unit on trademarks and best for it is looking for the answers in-house related issues, as the global petcare business has been managed from St Louis since the acquisition of Ralston Purina in 2001. In parallel, 16 regional IP advisers spread around the world advise the Nestlé Imagine that you start your day with a glass of VITTEL water operating companies (there were 487 production sites worldwide at followed by a cup of CARNATION Instant Breakfast drink. Mid- the end of 2005) on all aspects of intellectual property, including morning you have a cup of NESCAFÉ instant coffee and snack on a trademarks, with a particular focus on local marks. The trademark cheeky KIT KAT chocolate bar; lunch is a HERTA sausage with group also includes a dedicated lawyer in Vevey who manages the BUITONI pasta-and-sauce affair, finished off by a SKI yogurt. -

Industrial Chocolate Manufacture and Use

INDUSTRIAL CHOCOLATE MANUFACTURE AND USE Industrial Chocolate Manufacture and Use: Fourth Edition. Edited by Stephen T. Beckett © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN: 978-1-405-13949-6 SSBeckett_FM.inddBeckett_FM.indd i 110/1/20080/1/2008 110:00:430:00:43 AAMM INDUSTRIAL CHOCOLATE MANUFACTURE AND USE Fourth Edition Edited by Stephen T. Beckett Formerly Nestlé PTC York, UK SSBeckett_FM.inddBeckett_FM.indd iiiiii 110/1/20080/1/2008 110:00:440:00:44 AAMM This edition fi rst published 2009 Third edition published 1999 Second edition published 1994 by Chapman and Hall First edition published 1988 by Chapman and Hall © 1999, 2009 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing programme has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial offi ces 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, United Kingdom 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USA For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Grocery Goliaths

HOW FOOD MONOPOLIES IMPACT CONSUMERS About Food & Water Watch Food & Water Watch works to ensure the food, water and fish we consume is safe, accessible and sustainable. So we can all enjoy and trust in what we eat and drink, we help people take charge of where their food comes from, keep clean, affordable, public tap water flowing freely to our homes, protect the environmental quality of oceans, force government to do its job protecting citizens, and educate about the importance of keeping shared resources under public control. Food & Water Watch California Office 1616 P St. NW, Ste. 300 1814 Franklin St., Ste. 1100 Washington, DC 20036 Oakland, CA 94612 tel: (202) 683-2500 tel: (510) 922-0720 fax: (202) 683-2501 fax: (510) 922-0723 [email protected] [email protected] foodandwaterwatch.org Copyright © December 2013 by Food & Water Watch. All rights reserved. This report can be viewed or downloaded at foodandwaterwatch.org. HOW FOOD MONOPOLIES IMPACT CONSUMERS Executive Summary . 2 Introduction . 3 Supersizing the Supermarket . 3 The Rise of Monolithic Food Manufacturers. 4 Intense consolidation throughout the supermarket . 7 Consumer choice limited. 7 Storewide domination by a few firms . 8 Supermarket Strategies to Manipulate Shoppers . 9 Sensory manipulation . .10 Product placement . .10 Slotting fees and category captains . .11 Advertising and promotions . .11 Conclusion and Recommendations. .12 Appendix A: Market Share of 100 Grocery Items . .13 Appendix B: Top Food Conglomerates’ Widespread Presence in the Grocery Store . .27 Methodology . .29 Endnotes. .30 Executive Summary Safeway.4 Walmart alone sold nearly a third (28.8 5 Groceries are big business, with Americans spending percent) of all groceries in 2012. -

Chaplin's World by Grévin Is Opening a New Boutique and an Additional Events Venue

PRESS RELEASE CHAPLIN’S WORLD BY GRÉVIN IS OPENING A NEW BOUTIQUE AND AN ADDITIONAL EVENTS VENUE Corsier-sur-Vevey, 10 July 2018 – Chaplin’s World by Grévin, the museum dedicated to the life and work of Charlie Chaplin, is proud to announce the opening of a new boutique in the artist’s former home, the Manoir de Ban. The boutique will delight food- lovers with its fine tableware, chocolate, and the Manoir’s own honey, produced on the estate. The Manoir wine cellars, once used to store Chaplin’s films, have been completely refurbished and are now available for private events. A NEW BOUTIQUE IN CHAPLIN’S KITCHEN Located in the Chaplins’ former kitchen at the Manoir de Ban, the design of our new boutique is inspired by a 19th-century kitchen, with quintessentially British retro floral patterns. It features a wide range of vintage cooking utensils and culinary art items (aprons, tableware, etc.). A pleasure to the eye as well as the taste buds, assorted Cailler chocolates in Charlie Chaplin packaging will delight the most discerning chocolate lover. The Fémina, Ambassador and Frigor chocolate pralines are presented in boxes designed exclusively for the museum. It was an obvious choice to team up with this heritage brand, founded just a short walk from the Manoir almost 200 years ago. The partnership brings together two of the region’s icons, helping to expand their renown beyond local borders. Made with milk from local pastures in the Broc-en-Gruyère area, the IP-SUISSE-certified Cailler chocolate will meet our international visitors’ frequent demand for Swiss chocolate. -

Consommation : Fiche D'information De La DB Sur Le Chocolat

Consommation: fiChe d’information de 01 la dB sur le ChoColat 01_mars_11 ChoColat Un arrière-goût d’exploitation Près de 70 pour cent de la production mondiale de cacao provient d’Afrique de l’Ouest. Dans les plantations de Côte d’Ivoire et du Ghana, le travail et l’esclavage des enfants sont monnaie courante. L’industrie chocolatière, qui est parfaitement au courant de ce scandale depuis de nombreuses années, porte une lourde part de responsabilité. Afin de garantir de meilleures conditions de travail, les grandes entreprises du secteur doivent garantir des prix décents aux producteurs et une plus grande transparence sur l’ensemble de leur filière d’approvisionnement. ChoColat__2 aperçu Dans le monde, il y a environ 5,5 millions d’agriculteurs qui produisent du cacao. Un tiers de cette production vient de Côte d’Ivoire et 20 pour cent proviennent du Ghana. Le Nige- ria, le Cameroun, l’Indonésie, le Brésil et l’Equateur fournissent le reste. Les petits produc- teurs vendent leurs fèves à des entreprises de transformation qui confectionnent les pro- duits de bases pour la fabrication du chocolat. Le marché mondial des produits à base de cacao est dominé par un petit nombre de multinationales qui en retirent les principaux bé- néfices. En effet, moins de 5 pour cent du prix d’une tablette revient dans les poches des producteurs de cacao. Ces dernières années, les problèmes écologiques et sociaux liés à la production de cacao se sont aggravés. Les revenus des producteurs, qui étaient déjà très bas, ont fondus sous le coup de la baisse des prix de la matière première. -

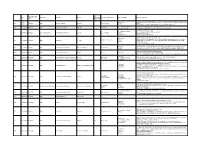

Category of Supplement Types of Claims Examples of Claims (2007) Enforceme Nt? •Germs Are Everywhere

Referred to Gov Date of Decision Type Challenger Advertiser Product Agency for Category of Supplement Types of Claims Examples of Claims (2007) Enforceme nt? •Germs are everywhere. Take Airborne to boost your immune system, fight viruses and help you stay Case •Performance 4648 3/26/2007 NAD Airborne Health Inc. Airborne Immune Health healthy. Report •Implied •Take Airborne. The immune boosting tablet that helps your body fight germs. •Clinically Proven/Shown •CH-Alpha is scientifically proven to promote joint health. 4652 Case Report 4/10/2007 NAD Gelita Health Products CH-Alpha Joint Health •Preventative Health •After just two to three months, you will regain the freedom of flexibility. •94% faster recovery [from colds] •Clinically Proven/Shown •Increased immune system resistance by 312% 4653 Case Report 4/10/2007 Proctor and Gamble Iovate Health Sciences Inc. Cold MD Immune Health •Speed •Clinically Proven results •Comparative •Doctor formulated and approved •Chromax helps your insulin function at its best. •Performance •It's an advanced, highly absorbable form of chromium that provides your body with the chromium it Blood Sugar Health •Insulin 4547 Compliance 4/11/2007 NAD Nutrition 21 Chromax needs to help promote healthy blood sugar, fight carbohydrate cravings and support your overall •Implied cardiovascular health. •Essential for optimum insulin health. •Exclusivity •One-A-Day Women's Multi-Vitamin is the only complete multi-vitamin with more calcium for strong 4672 Case Report 5/1/2007 NAD Bayer Consumer Healthcare One-A-Day Women's Multi-Vitamin •Implied bones, and now more vitamin D, which emerging research suggests may support breast cancer. -

The World Health Organization Is Taking Cash Handouts from Junk Food Giants by Vigilant Citizen October 23, 2012

The World Health Organization is Taking Cash Handouts from Junk Food Giants By Vigilant Citizen October 23, 2012 The World Health Organization (WHO) is the United Nationʼs “public health” arm and has 194 member states. While its official mission is “the attainment by all people of the highest possible level of health“, it is also clear that it works according to a specific agenda, one that laid out by the world elite and the organizations that are part of it. In the article entitled ‘Contagionʼ or How Disaster Movies “Educate” the Masses, weʼve seen how the WHO was involved in the promotion of mass vaccination campaigns following (bogus) disease scares, of civilian camps, of the bar-coding of individuals and so forth. More proof of the WHOʼs “elite bias” has been recently uncovered by a study: The organization has been taking hundreds of thousands of dollars from the worldʼs biggest pushers of unhealthy foods such as Coca-Cola, Nestlé and Unilever. It is relying on these companies for advice on how to fight obesity..é which is the equivalent of asking a drug dealer for advice on how stay off drugs and NOT buy his product. Coca-Cola, Nestlé and Unilever are not simply “food companies, they are gigantic conglomerates that produce and distribute an enormous proportion of processed foods across the world. In the article entitled Irrational Consumerism (or The Few Companies Who Feed the World), I described how only a few mega-conglomerates own most of the worldʼs brands of processed foods. To refresh your memory here are some of the brands