Group Cohesion and the Mitigating Potential of Private Actors in Conflict Negotiation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Student Officers: President: Mohamed El Habbak Chairs: Adam Beblawy, Ibrahim Shoukry

Forum: Security Council Issue: The Israeli-Palestinian conflict Student Officers: President: Mohamed El Habbak Chairs: Adam Beblawy, Ibrahim Shoukry Introduction: Beginning in the mid-20th century, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the still continuing dispute between Israel and Palestine and part of the larger Arab-Israeli conflict, and is known as the world’s “most intractable conflict.” Despite efforts to reach long-term peace, both parties have failed to reach a final agreement. The crux of the problem lies in a few major points including security, borders, water rights, control of Jerusalem, Israeli settlements, Palestinian freedom of movement, and Palestinian right of return. Furthermore, a hallmark of the conflict is the level of violence for practically the entirety of the conflict, which hasn’t been confined only to the military, but has been prevalent in civilian populations. The main solution proposed to end the conflict is the two-state solution, which is supported by the majority of Palestinians and Israelis. However, no consensus has been reached and negotiations are still underway to this day. The gravity of this conflict is significant as lives are on the line every day, multiple human rights violations take place frequently, Israel has an alleged nuclear arsenal, and the rise of some terroristic groups and ideologies are directly linked to it. Key Terms: Gaza Strip: Region of Palestine under Egyptian control. Balfour Declaration: British promise to the Jewish people to create a sovereign state for them. Golan Heights: Syrian territory under Israeli control. West Bank: Palestinian sovereign territory under Jordanian protection. Focused Overview: To understand this struggle, one must examine the origins of each group’s claim to the land. -

2018-2019 Model Arab League BACKGROUND GUIDE Council on Palestinian Affairs Ncusar.Org/Modelarableague

2018-2019 Model Arab League BACKGROUND GUIDE Council on Palestinian Affairs ncusar.org/modelarableague Original draft by Jamila Velez Khader, Chair of the Council on Palestinian Affairs at the 2019 National University Model Arab League, with contributions from the dedicated staff and volunteers at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations Topic I: Devising strategies to plan for potential failure of peace negotiations. I. Introduction to the Topic A. General Background As early as 1947, Palestinian Arabs and Jews have wanted to undertake peace negotiations under the auspice of the United Nations. However, 1991 was the start of the series of peace negotiations between Israel and Palestine.1 The series of peace negotiations have produced a collection of peace plans, international summits, secret negotiations, UN resolutions, think tanks, initiatives, interim truces and state-building programmes, etc that have all failed. The reasons for why each peace negotiation has faltered is because each peace plan has failed to address key issues at a local, regional and global level for all parties involved. The main players in these negotiations include the Palestinian government, political parties of Palestine, the Israeli State, and members of the Arab League and United Nations. The most recent peace plan between one of Palestine’s prominent political parties, Hamas, which governs Gaza, took place with Israel in Cairo, Egypt. Currently, Egypt is finalizing the details of a one year truce that could extend to four years.2 Although this can be considered progress, it is only short term. A truce up to four years is not sustainable and does not resolve the larger issues at hand which include: Palestinian statehood, border placement, rights of Palestinian refugees and diaspora, Israeli settlements and the role of Arab League and United Nations. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Presidium Model United Nations 13Th-14Th August 2021

Presidium Model United Nations 13th-14th August 2021 The United Nations Human Rights Council Agenda: The Israel-Palestine Conflict 1 LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE BOARD The Executive Board of Presidium Model United Nations welcomes each one of you. For many it may be the first ever MUN conference in your educational experience, and we strongly encourage you to go through the study guide that has been prepared for you as a part of the conference in order to get an in depth understanding of the issue that will be discussed in the committee. However, there is lot of content available beyond the study guides too. You are expected to research, collate, list down possible points of discussions, questions and plausible responses and be prepared to enjoy the intellectual energy in the group. At the same time it is not only about speaking and presenting, but very importantly it is also about the ability to listen, understand view points and learn from each one’s perspectives. Wishing all of you a great learning experience. Looking forward to having you all with us. Best wishes The Executive Board 1. Akul Halan (President) 2. Vansham Mudgil (Vice-President) 3. Sonal Gupta (Substantial Director) 2 The United Nations Security Council The Human Rights Council is an intergovernmental body of the United Nations, through which States discuss human rights conditions in the UN Member States. The Council’s mandate is to promote “universal respect for the protection of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all” and “address situations of violations of human rights, including gross and systematic violations, and make recommendations thereon.” The Human Rights Council was established in 2006 by Resolution 60/251 as a subsidiary body to the UN General Assembly. -

Advocating for Israel: History, Tools and Tips a Message from the Baltimore Jewish Council: TABLE of CONTENTS

Advocating for Israel: History, Tools and Tips A Message from the Baltimore Jewish Council: TABLE OF CONTENTS The publication of this guide, Advocating for Israel: History, Tools and Tips, provides an opportunity for Introduction those who support Israel to become more involved in advocating on its behalf. It is designed for those who are becoming politically active for the first time, as well as seasoned Israel supporters. Event Timeline…………………………………………………………………………………………...2 While many people have traveled to Israel, attended lectures, and/or read about the country, there are Israel: Background…………………………………………………………………………………...….7 many who are not aware or comfortable with the process of advocacy. The purpose of this guide is to help bridge that gap. Key Words and Common Terms About Israel………………………………..………………………. 9 This guide was not created for a “one-time” event; it is a resource that can sit in your home, office, Understanding Israel’s Government…………………………...………………………………………11 classroom, or backpack and may be referred to at any time. Israel: Some Facts………………………….……………………………………………………………13 Information in this guide was developed from a variety of publications and web-based sources. We have Advocating for Israel………………...………………………………………………………...........…14 made every effort to confirm the veracity of the facts presented. Writing a Letter to Your Representative………………………………………………………………..15 To become more involved in Israel advocacy, please contact the Baltimore Jewish Council at Meeting With Officials………………………………………………………………………………….17 410-542-4850 -

View/Print Page As PDF

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Armistice Now: An Interim Agreement for Israel and Palestine Feb 24, 2010 Articles & Testimony R ead this article at ForeignAffairs.com More than 16 years after the euphoria of the Oslo accords, the Israelis and the Palestinians have still not reached a final-status peace agreement. Indeed, the last decade has been dominated by setbacks -- the second intifada, which started in September 2000; Hamas' victory in the January 2006 Palestinian legislative elections; and then its military takeover of the Gaza Strip in June 2007 -- all of which have aggravated the conflict. A further effort to reach a comprehensive settlement is bound to falter, thus increasing the dangers of another major flare-up and undermining the credibility of the Palestinian Authority (PA). The prospects of a deal between Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and PA President Mahmoud Abbas are slim, since Abbas already rejected former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert's far-reaching proposals -- the sort of offer Netanyahu would never make. This diplomatic stalemate discredits moderates and plays into the hands of extremists on both sides who refuse to make the concessions that any viable peace treaty will require. Since an extended impasse is so dangerous, the best option for both the Israelis and the Palestinians is to seek a less ambitious agreement that transforms the situation on the ground and creates momentum for further negotiations by establishing a Palestinian state within armistice boundaries. In diplomatic terms, this formula would go beyond phase two of George W. Bush's 2002 "road map for peace," which proposed a Palestinian state with provisional boundaries, by striving to reach interim agreements on all the issues but stopping short of actually resolving the final-status issues of Jerusalem, the fate of the Palestinian refugees, and permanent boundaries, which were envisioned as phase three of Bush's road map. -

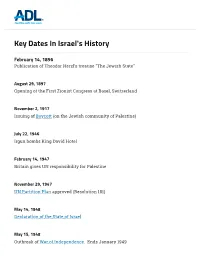

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution -

Routledge Handbook of U.S. Counterterrorism and Irregular

‘A unique, exceptional volume of compelling, thoughtful, and informative essays on the subjects of irregular warfare, counter-insurgency, and counter-terrorism – endeavors that will, unfortunately, continue to be unavoidable and necessary, even as the U.S. and our allies and partners shift our focus to Asia and the Pacific in an era of renewed great power rivalries. The co-editors – the late Michael Sheehan, a brilliant comrade in uniform and beyond, Liam Collins, one of America’s most talented and accomplished special operators and scholars on these subjects, and Erich Marquardt, the founding editor of the CTC Sentinel – have done a masterful job of assembling the works of the best and brightest on these subjects – subjects that will continue to demand our attention, resources, and commitment.’ General (ret.) David Petraeus, former Commander of the Surge in Afghanistan, U.S. Central Command, and Coalition Forces in Afghanistan and former Director of the CIA ‘Terrorism will continue to be a featured security challenge for the foreseeable future. We need to be careful about losing the intellectual and practical expertise hard-won over the last twenty years. This handbook, the brainchild of my late friend and longtime counter-terrorism expert Michael Sheehan, is an extraordinary resource for future policymakers and CT practitioners who will grapple with the evolving terrorism threat.’ General (ret.) Joseph Votel, former commander of US Special Operations Command and US Central Command ‘This volume will be essential reading for a new generation of practitioners and scholars. Providing vibrant first-hand accounts from experts in counterterrorism and irregular warfare, from 9/11 until the present, this book presents a blueprint of recent efforts and impending challenges. -

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Historical and Prospective Intervention Analyses

Special Conflict Report The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Historical and Prospective Intervention Analyses October 18-20, 2002 Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. The Carter Center strives to relieve suffering by advancing peace and health worldwide; it seeks to prevent and resolve conflicts, enhance freedom and democracy, and protect and promote human rights worldwide. The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Historical and Prospective Intervention Analyses October 18–20, 2002 One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5185 Fax (404) 420-3862 www.cartercenter.org July 2003 The Carter Center The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Foreword eptember will mark the 25th anniversary one environment may be useful in addressing similar of the Camp David Peace Accords. That issues in a totally different environment. In this historic moment remains the high-water report, we strive to distill the most important mark for diplomacy in the Middle East. elements that emerged from two days of discussions To this day, not one element of that agree- into a brief and useful document that may provide Sment has been violated; Egypt and Israel remain at insights on how to advance discussions regarding peace. September also will mark the 10th anniversary the final settlement of the Israel-Palestine conflict of the Oslo Peace Accords, which provided the first once that stage is reached. real opportunity to resolve perhaps the most difficult I would like to express my appreciation to those of the remaining elements required for regional peace participants: Professor Mari Fitzduff from INCORE and stability: an agreement between Israel and its in Belfast; Joseph Montville, formerly director of Palestinian neighbors. -

Israel - Palestine Conflict - a Tale of Grave Human Violations & Innumerable Casualties

RESEARCH PAPER Law Volume : 4 | Issue : 9 | September 2014 | ISSN - 2249-555X Israel - Palestine Conflict - A Tale of Grave Human Violations & Innumerable Casualties KEYWORDS Mr.Manish Dalal Mr.ArunKumar Singh Assistant Professor in Law Noida International First year, Faculty of Law, Noida International University University * Corresponding author ABSTRACT Israel - Palestine conflict is one of the most burning issues of modern times which poses a big threat to international peace & security. This conflict is an example of grave human rights violations & a large no. of human causalities’. The warring sides are the Israeli government on the one hand and a group named Hamas which is controlling Gaza Strip after winning the elections in 2006 on the other hand. Hamas is mostly viewed as a terrorist organization all over the world. Both Israel & Hamas do not recognize each other's authority & ready to use violence to achieve their means. But to understand the reasons for this conflict one has to go back to history in the middle of 20th century where it all started. Introduction The First Palestinian Intifada The history of this war dates back to the year 1948 with The First Palestinian Intifada also known as a the first Pal- the declaration of State of Israel on 15th May, 1948 which estinian uprising against the Israeli occupation began on didn’t go down well with the Arab League which pro- 8th December, 1987 & ended on 13th September, 1993 claimed that the entire area given to Israel belongs to with the signing of Oslo Accords. It was the first biggest them & it didn’t recognize Israel as a State giving rise to uprising against Israel after their 1967 occupation of the 1948 Arab-Israel war in which many people lost their lives disputed territory of Gaza Strip, West Bank & East Jerusa- & many more became refugees. -

The Annapolis Conference: a Chronic Case of Too Little, Too Late?

THE ANNAPOLIS CONFERENCE: A CHRONIC CASE OF TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE? A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Liberal Studies By Marta P. Silva, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. December 1, 2010 THE ANNAPOLIS CONFERENCE: A CHRONIC CASE OF TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE? Marta P. Silva, B.A. Mentor: Ralph Nurnberger, Ph.D. ABSTRACT On November 26- 27, 2007, President George W. Bush and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice organized the Annapolis Peace Conference, the first international conference to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on American soil. It was held at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The conference brought together representatives from 49 states and organizations. The presence of such a diverse group demonstrated strong support for a resolution to the Israeli-conflict and for Ehud Olmert, Prime Minister of Israel and Mahmoud Abbas, President of the Palestinian National Authority as peace negotiators. This thesis analyzes why the Annapolis Peace Conference failed to resolve the Israel-Palestinian conflict. The United States’ long term myopia to the geopolitical realities of the Jewish/Muslim relationship has caused a pernicious, on-going stalemate in the Middle East. The discussion here begins with the analysis of the Bush administration’s policies throughout the two terms and then looks at the yearlong events leading up to the conference. The analysis concludes that the Bush administration’s lack of concern for the conflict during the President’s first term; the geopolitical fallout from the attacks on September 11, 2001; lack of enforcement of the Annapolis Peace Conference provisions; ii missed diplomatic and political leverage opportunities; and the political weakness of all three leaders during and after the Annapolis Peace Conference led to the failure of the Annapolis Peace Conference. -

Beyond Annapolis. the Case for a Stronger EU Engagement by Muriel Asseburg and Volker Perthes*

BEPA Monthly Brief - Issue 12, February 2008 1 Beyond Annapolis. The Case for a Stronger EU Engagement By Muriel Asseburg and Volker Perthes* In January 2008 peace making on the Israeli- and Ramallah and the Palestinian Authority has Palestinian track was relegated, once more, to focused on restoring law and order in West Bank the backburner. Israeli and Palestinian leaders cities. Yet, other Phase One commitments have were consumed by crisis management as not seen any progress. Neither have significant increased rocket fire on Israel had prompted an steps been taken to normalise Palestinian life, intensified blockade of the Gaza Strip and the nor have settlement outposts been dismantled or break-out of hundreds of thousands of Gaza building in settlements stopped effectively. residents after militants linked to Hamas had Palestinian institutions in East Jerusalem have blown open the border fence to Egypt. Those in not been reopened. And with the political split charge of the negotiations were also focused on between West Bank and Gaza Strip persisting, their own political survival. Israeli Prime comprehensive political reform in preparation Minister Ehud Olmert was under pressure to for Palestinian statehood has become illusory. resign in the context of the publication of the Moreover, the Annapolis process does not offer Winograd Committee’s final report. The stand- any constructive way of overcoming that split. It off between the adverse Palestinian governments rather builds on the “West Bank first” strategy in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip endured. adopted by the international community in Renewed peace process efforts kicked off with reaction to Hamas’ violent assumption of power great fanfare by the American administration in in the Gaza Strip last June.