Tackling Racism Seriously

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

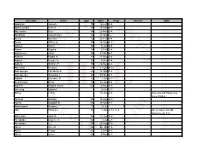

Hamilton County (Ohio) Naturalization Records – Surname M

Hamilton County Naturalization Records – Surname M Applicant Age Country of Origin Departure Date Departure Port Arrive Date Entry Port Declaration Dec Date Vol Page Folder Naturalization Naturalization Date Maag, Frederick 46 Oldenburg Bremen New Orleans T 11/01/1852 5 132 F F Maag, Frederick 46 Oldenburg Bremen New Orleans T 11/01/1854 6 258 F F Maag, Sebastian 31 Baden Liverpool New York T 01/02/1858 16 296 F F Maahan, James 32 Ireland Toronto Buffalo T 01/20/1852 24 37 F F Maas, Anton 30 Prussia Bremen New York T 01/17/1853 7 34 F F Maas, Carl 18 Mannheim, Germany ? ? T 05/04/1885 T F Maas, Garrett William 25 Holland Rotterdam New York T 11/15/1852 5 287 F F Maas, Garrett William 25 Holland Rotterdam New York T 11/15/1852 6 411 F F Maas, Jacob 55 Germany Rotterdam New York F ? T T Maas, John 55 Germany Havre New York F ? T T Maas, John William 28 Holland Rotterdam New Orleans T 09/27/1848 22 56 F F Maas, Julius J. 48 Germany Bremen New York F ? T T Maas, Leonardus Aloysius 37 Holland Rotterdam New Orleans T 03/01/1852 24 6 F F Maass, F.W. 45 Hanover Bremen Baltimmore T 11/02/1860 18 3 F F Macalusa, Michael 23 Italy Palermo New York T 3/18/1903 T F MacAvoy, Henry 48 England Liverpool New York T 10/26/1891 T F MacDermott, Joseph England ? ? T 2/26/1900 T F Machenheimer, Christoph 29 Hesse Darmstadt Havre New York T 02/19/1850 2 100 F F Machnovitz, Moses 50 Russia Bremen Baltimore T 4/27/1900 T F Maciejensky, Martin 28 Prussia Hamburg New York T 04/28/1854 8 280 F F Maciejensky, Martin 28 Prussia Hamburg New York T 04/28/1854 9 151 F -

18Th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference (SGEM

18th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference (SGEM 2018) Conference Proceedings Volume 18 Albena, Bulgaria 2 - 8 July 2018 Issue 1.1, Part A ISBN: 978-1-5108-7357-5 1/26 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2018) by International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM) All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2019) For permission requests, please contact International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM) at the address below. International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM) 51 Alexander Malinov Blvd. fl 4, Office B5 1712 Sofia, Bulgaria Phone: +359 2 405 18 41 Fax: +359 2 405 18 65 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com Contents CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS CONTENTS GEOLOGY 1. A PRELIMINARY EVALUATION OF BULDAN COALS (DENIZLI/WESTERN TURKEY) USING PYROLYSIS AND ORGANIC PETROGRAPHIC INVESTIGATIONS, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Demet Banu KORALAY, Zuhal Gedik VURAL, Pamukkale University, Turkey ..................................................... 3 2. ANCIENT MIDDLE-CARBONIFEROUS FLORA OF THE ORULGAN RANGE (NORTHERN VERKHOYANSK) AND JUSTIFICATION OF AGE BYLYKAT FORMATION, Mr. A.N. Kilyasov, Diamond and Precious Metal Geology Institute, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (DPMGI SB RAS), Russia ................................................................................................................... 11 3. BARIUM PHLOGOPITE FROM KIMBERLITE PIPES OF CENTRAL YAKUTIA, Nikolay Oparin, Ph.D. Oleg Oleinikov, Institute of Geology of Diamond and Noble Metals SB RAS, Russia ................................................................................ -

Association of Accredited Lobbyists to the European Parliament

ASSOCIATION OF ACCREDITED LOBBYISTS TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT OVERVIEW OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT FORUMS AALEP Secretariat Date: October 2007 Avenue Milcamps 19 B-1030 Brussels Tel: 32 2 735 93 39 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lobby-network.eu TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………..3 Executive Summary……………………………………………………….4-7 1. European Energy Forum (EEF)………………………………………..8-16 2. European Internet Forum (EIF)………………………………………..17-27 3. European Parliament Ceramics Forum (EPCF………………………...28-29 4. European Parliamentary Financial Services Forum (EPFSF)…………30-36 5. European Parliament Life Sciences Circle (ELSC)……………………37 6. Forum for Automobile and Society (FAS)…………………………….38-43 7. Forum for the Future of Nuclear Energy (FFNE)……………………..44 8. Forum in the European Parliament for Construction (FOCOPE)……..45-46 9. Pharmaceutical Forum…………………………………………………48-60 10.The Kangaroo Group…………………………………………………..61-70 11.Transatlantic Policy Network (TPN)…………………………………..71-79 Conclusions………………………………………………………………..80 Index of Listed Companies………………………………………………..81-90 Index of Listed MEPs……………………………………………………..91-96 Most Active MEPs participating in Business Forums…………………….97 2 INTRODUCTION Businessmen long for certainty. They long to know what the decision-makers are thinking, so they can plan ahead. They yearn to be in the loop, to have the drop on things. It is the genius of the lobbyists and the consultants to understand this need, and to satisfy it in the most imaginative way. Business forums are vehicles for forging links and maintain a dialogue with business, industrial and trade organisations. They allow the discussions of general and pre-legislative issues in a different context from lobbying contacts about specific matters. They provide an opportunity to get Members of the European Parliament and other decision-makers from the European institutions together with various business sectors. -

Voorbij De Retoriek

Ieke van den Burg, Jan Cremers, Voorbij de retoriek Voorbij Camiel Hamans en Annelies Pilon (red.) Voorbij de retoriek Sociaal Europa vanuit twaalf invalshoeken Voorbij de retoriek Voorbij de retoriek Sociaal Europa vanuit twaalf invalshoeken Ieke van den Burg, Jan Cremers, Camiel Hamans & Annelies Pilon (red.) In samenwerking met Eerste druk mei 2014 © Wiardi Beckman Stichting | Uitgeverij Van Gennep Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal 330, 1012 rw Amsterdam Ontwerp omslag Léon Groen Drukwerk Koninklijke Wöhrmann, Zutphen isbn 978 94 6164 328 5 | nur 740 www.wbs.nl www.uitgeverijvangennep.nl Inhoud Sociaal Europa: ingrijpen gewenst Een inleiding Ieke van den Burg & Jan Cremers 7 1 De missie van Delors Jan Cremers 21 2 Europa’s banencrisis Bescherm goed werk én vrij verkeer Lodewijk Asscher 29 3 ‘Wij willen gehoord worden’ ROC-studenten in Groningen Michiel Emmelkamp 39 4 De financialisering van de Nederlandse verzorgingsstaat Ieke van den Burg 41 5 Sociale mensenrechten als opdracht Kathalijne Buitenweg & Rob Buitenweg 57 6 De race naar de Europese top Paul Tang 67 7 Het paard achter de wagen Europese crisisaanpak bedreigt nationale en Europese sociale dialoog Marjolijn Bulk & Catelene Passchier 77 8 ‘Wij hebben open grenzen nodig’ Paprikatelers in Heusden Michiel Emmelkamp 89 9 Concurreren met behulp van detacheringsarbeid Mijke Houwerzijl 91 10 Sociale zekerheid en vrij verkeer Jan Cremers 107 11 Toenemende bestaansonzekerheid bij kinderen EU moet daad bij het woord voegen Frank Vandenbroucke & Rik Wisselink 121 12 Is sociaal Europa het antwoord -

STATE RECORDKEEPING in the CLOUD Lorraine L. Richards A

EVIDENCE-AS-A-SERVICE: STATE RECORDKEEPING IN THE CLOUD Lorraine L. Richards A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School Information and Library Science. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher A. Lee Helen R. Tibbo Richard Marciano Jeffrey Pomerantz Theresa A. Pardo © 2014 Lorraine L. Richards ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Lorraine L. Richards: Evidence-as-a-Service: State Recordkeeping in the Cloud (Under the Direction of Christopher A. Lee) The White House has engaged in recent years in efforts to ensure greater citizen access to government information and greater efficiency and effectiveness in managing that information. The Open Data policy and recent directives requiring that federal agencies create capacity to share scientific data have fallen on the heels of the Federal Government’s “Cloud First” policy, an initiative requiring Federal agencies to consider using cloud computing before making IT investments. Still, much of the information accessed by the public resides in the hands of state and local records creators. Thus, this exploratory study sought to examine how cloud computing actually affects public information recordkeeping stewards. Specifically, it investigated whether recordkeeping stewards’ concerns about cloud computing risks are similar to published risks in newly implemented cloud computing environments, it examined their perceptions of how cross-occupational relationships affect their ability to perform recordkeeping responsibilities in the Cloud, and it compared how recordkeeping roles and responsibilities are distributed within their organizations. The distribution was compared to published reports of recordkeeping roles and responsibilities in archives and records management journals published over the past 42 years. -

The Netherlands in the EU: from the Centre to the Margins?

Adriaan Schout and Jan Marinus Wiersma The Netherlands in the EU: From the Centre to the Margins? 1. From internal market narrative to a narrative of uncertainties In this post-2008 era of European integration, every year seems to have specific – and fundamental – European challenges. For the Netherlands, 2012 was a year in which it was highly uncertain how the Dutch would vote.1 The rather populist anti-EU party of Geert Wilders (PVV-Freedom Party) had proclaimed that the elections would be about and against the European Union. This strategy did not pay off as people voted for stability, also regarding the EU. However, existential doubts about European integration and the euro have persisted and even increased as the emergence of a referendum movement in early 2013 has shown. Although the number of signatures supporting the idea to consider a referendum about the future of the EU rose to close to 60.000 in a couple of months, anti-EU feelings have found less support than one could have expected on the basis of opinion polls. Nevertheless, a strong and persistent doubt about the EU seems evident in the Netherlands even though it has a fairly low level of priority in daily policy debates. For once because there are few real EU issues on the agenda and, secondly, because discussions on, for instance, Treaty changes or the meaning of a ‘political union’ are being downplayed. Pew Research2 showed that 39% of the Dutch would like to leave the EU and Eurobarometer indicates a drop in public support from 60% in 2012 to 45% in 2013. -

Beyond the Deadlock? Perspectives on Future EU Enlargement

Beyond the deadlock? Perspectives on future EU enlargement E-publication edited Joost Lagendijk and Jan Marinus Wiersma Clingendael Institute, The Hague, 2012 © Clingendael Institute Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague Phone: + 31-70-3141950 Telefax: + 31-70-3141960 Email: [email protected] Website: www.clingendael.nl © Clingendael Institute Note of the Editors The Netherlands Institute for International Relations Clingendael hosted a one-day seminar on the future of EU enlargement on the 29th of November 2011. The event was chaired by Joost Lagendijk, Senior Advisor Istanbul Policy Center, and Jan Marinus Wiersma, Senior Visiting Fellow Clingendael. As the title of the conference – Beyond the deadlock? Perspectives on future EU enlargement – indicates, the debate concentrated on the differences between the accession rounds of 2004 and 2007 en the one that is now under way. Both the EU and the (potential) candidate countries operate in a different context that is marked by a much stricter conditionality of the EU which has a negative impact on the speed of the enlargement process. The countries in question, with the possible exception of Iceland, are confronted with internal opposition to the EU, sometimes show a lack of reform mindedness and have difficulty coping with political obstacles like the Cyprus issue in the case of Turkey or the Kosovo question. The agenda of the seminar consisted of three main topics: lessons learned from past accessions, the cases of Turkey and Macedonia, and the future of enlargement. They are being dealt with in this publication from different angles. -

Het Hof Van Brussel of Hoe Europa Nederland Overneemt

Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt Arendo Joustra bron Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt. Ooievaar, Amsterdam 2000 (2de druk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/jous008hofv01_01/colofon.php © 2016 dbnl / Arendo Joustra 5 Voor mijn vader Sj. Joustra (1921-1996) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 6 ‘Het hele recht, het hele idee van een eenwordend Europa, wordt gedragen door een leger mensen dat op zoek is naar een volgende bestemming, die het blijkbaar niet in zichzelf heeft kunnen vinden, of in de liefde. Het leger offert zich moedwillig op aan dit traagkruipende monster zonder zich af te vragen waar het vandaan komt, en nog wezenlijker, of het wel bestaat.’ Oscar van den Boogaard, Fremdkörper (1991) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 9 Inleiding - Aan het hof van Brussel Het verhaal over de Europese Unie begint in Brussel. Want de hoofdstad van België is tevens de zetel van de voornaamste Europese instellingen. Feitelijk is Brussel de ongekroonde hoofdstad van de Europese superstaat. Hier komt de wetgeving vandaan waaraan in de vijftien lidstaten van de Europese Unie niets meer kan worden veranderd. Dat is wennen voor de nationale hoofdsteden en regeringscentra als het Binnenhof in Den Haag. Het spel om de macht speelt zich immers niet langer uitsluitend af in de vertrouwde omgeving van de Ridderzaal. Het is verschoven naar Brussel. Vrijwel ongemerkt hebben diplomaten en Europese functionarissen de macht op het Binnenhof veroverd en besturen zij in alle stilte, ongezien en ongecontroleerd, vanuit Brussel de ‘deelstaat’ Nederland. -

European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology a B

a eawop European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology a b 16thEAWOP Congress 2013 May 22nd-25th, 2013 in Münster b Contents c Contents Welcome Notes .......................................................................................................................................I Congress Theme ............................................................................................................................... VII Committees and Congress Office ............................................................................................VIII Reviewers ................................................................................................................................................IX Awards at the EAWOP Congress 2013 ........................................................................................ X Social Activities .................................................................................................................................. XIII Program Highlights............................................................................................................................XV Practitioner Sessions ......................................................................................................................XVII Program Overview ........................................................................................................................... XIX Detailed Program: Wednesday, May 22nd, 2013 Preconference Workshops ................................................................................................................1 -

Temas E Sessões Internas

ACTAS DE BIOQUÍMICA VOLUME 5 TEMAS E SESSÕES INTERNAS Editors J. Martins e Silva Carlota Saldanha 1991 “Actas de Bioquímica ” is primarily concerned with the publication of complete transcripts of the lectures, conferences and other studies presented in Advanced Post-Graduate Courses or in Scientific Symposia organized or co-organized by the Instituto de Bioquímica, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa. Original or review articles and other scientific contributions in askin fields may also be included. Editors J. Martins e Silva Carlota Saldanha Editorial Office Instituto de Bioquímica, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa Av. Prof. Egas Moniz Lisboa – Portugal Mailing Address Actas de Bioquímica Apartado 4098 1500-001 Lisboa – Portugal Subscription Information Subscription price is $25.00 (twenty five US dollars) (twenty euros) per volume. An additional charge of $5,00 per volume is requested for post delivery outside Portugal. Payment should accompany all orders. Correspondence concerning subscription should be addressed to the mailing address above. ISBN: 972-590-076-6 Copyrigh@ 1991 by Instituto de Bioquímica, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa. All rights reserved. Printed in Portugal II ACTAS DE BIOQUÍMICA VOLUME 5 1991 ÍNDICE PREFÁCIO .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... V ARTIGOS Liposomes -

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Abdullah Joseph 70 5-Feb A-8 Abercrombie Bert H

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Abdullah Joseph 70 5-Feb A-8 Abercrombie Bert H. 88 29-Dec B-9 Abernathy Kate 84 22-Nov B-4 Abraham Joseph Ben 86 21-Mar D-2 Acela Michael 73 23-Feb A-4 Achor Arthur A. 58 16-Sep A-11 Adalay Steve 92 6-Jan B-6 Adam Sophia 78 3-Feb B-4 Adamczyk John 85 21-Oct B-7 Adams Edwin B. 81 27-Aug B-4 Adank Cassie R. 75 7-Dec A-4 Adank William F. 76 24-Dec A-8 Adelman Irving D. 59 31-Oct D-10 Adelsperger Elizabeth A. 60 18-Mar A-8 Adelsperger Susanna T. 82 25-Oct A-7 Adoba Michael, Sr. 80 1-Jun A-12 Aeschliman Betty 32 18-Jan B-4 Aguirre Regina Avilla 63 4-Nov A-6 Ahlering Edward 6-Oct C-7 Ahley Lillian 15-Jun A-6 Also spelled Haley see June 16 E-2 Ahmed Hassan 68 13-Aug A-9 Akers Edward W. 66 16-Mar A-7 Aksentijevic Rodney 15 8-Jul 1 Alb Florence 70 1-Jun A-12, C-5 Gives name as Alb Florence on C-5 Albertson Jack R. 59 11-Jun C-2 Alexander Eugene A. 62 7-Jul C-8 Alexander L.C. 58 20-Aug B-3 Allen Cleo D. 66 26-Jan A-6 Allen Frosty 65 2-Dec B-6 Allen Grace 65 9-Nov B-3 Allen James Virgil 55 19-Aug A-4 Allen Weber 62 2-Mar A-4 Alley George Wesley 54 4-Jan A-5 Alonzo Maria 73 15-Oct B-5 Altshuller Nathan D. -

Mathieu MEUNIER Evaluation Du Rôle De La Niche Hématopoïétique Dans L

THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ UNIVERSITÉ GRENOBLE ALPES Spécialité : MBS - Modèles, méthodes et algorithmes en biologie, santé et environnement Arrêté ministériel : 25 mai 2016 Présentée par Mathieu MEUNIER Thèse dirigée par Sophie PARK, Communauté Université Grenoble Alpes préparée au sein du Laboratoire CRI IAB - Centre de Recherche Oncologie/Développement - Institute for Advanced Biosciences dans l'École Doctorale Ingénierie pour la santé la Cognition et l'Environnement Evaluation du rôle de la niche hématopoïétique dans l'induction des syndromes myélodysplasiques: rôle de dicer1 et du stress oxydatif The implication of hematopoietic niche in induction of myelodysplastic syndromes: the role of Dicer1 and oxidative stress Thèse soutenue publiquement le 5 avril 2018, devant le jury composé de : Madame SOPHIE PARK PROFESSEUR DES UNIV - PRATICIEN HOSP., CHU GRENOBLE ALPES, Directeur de thèse Madame CATHERINE LACOMBE PROFESSEUR EMERITE, ASSISTANCE PUBLIQUE - HOPITAUX DE PARIS, Examinateur Monsieur PIERRE HAINAUT PROFESSEUR, UNIVERSITE GRENOBLE ALPES, Examinateur Madame PATRICIA AGUILAR MARTINEZ PROFESSEUR DES UNIV - PRATICIEN HOSP., UNIVERSITE DE MONTPELLIER, Rapporteur Monsieur JEAN-FRANÇOIS PEYRON DIRECTEUR DE RECHERCHE, UNIVERSITE DE NICE, Rapporteur Monsieur JEAN-YVES CAHN PROFESSEUR DES UNIV - PRATICIEN HOSP., CHU GRENOBLE ALPES, Président REMERCIEMENTS Je remercie Madame Patricia Aguilar-Martinez, Madame Catherine Lacombe, Monsieur Jean- François Peyron et Monsieur Pierre Hainaut pour avoir accepté d’être membre du jury. Merci pour le temps que vous avez consacré à lire et évaluer mon travail de thèse. Ce travail n’aurait pas été possible sans le soutien de l’Université Grenoble Alpes et l’association ARAMIS Alpes qui m’ont permis grâce à une allocation d’une bourse de me consacrer sereinement et entièrement à l’élaboration de ma thèse.