UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Table S1 the Four Gene Sets Derived from Gene Expression Profiles of Escs and Differentiated Cells

Table S1 The four gene sets derived from gene expression profiles of ESCs and differentiated cells Uniform High Uniform Low ES Up ES Down EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol 269261 Rpl12 11354 Abpa 68239 Krt42 15132 Hbb-bh1 67891 Rpl4 11537 Cfd 26380 Esrrb 15126 Hba-x 55949 Eef1b2 11698 Ambn 73703 Dppa2 15111 Hand2 18148 Npm1 11730 Ang3 67374 Jam2 65255 Asb4 67427 Rps20 11731 Ang2 22702 Zfp42 17292 Mesp1 15481 Hspa8 11807 Apoa2 58865 Tdh 19737 Rgs5 100041686 LOC100041686 11814 Apoc3 26388 Ifi202b 225518 Prdm6 11983 Atpif1 11945 Atp4b 11614 Nr0b1 20378 Frzb 19241 Tmsb4x 12007 Azgp1 76815 Calcoco2 12767 Cxcr4 20116 Rps8 12044 Bcl2a1a 219132 D14Ertd668e 103889 Hoxb2 20103 Rps5 12047 Bcl2a1d 381411 Gm1967 17701 Msx1 14694 Gnb2l1 12049 Bcl2l10 20899 Stra8 23796 Aplnr 19941 Rpl26 12096 Bglap1 78625 1700061G19Rik 12627 Cfc1 12070 Ngfrap1 12097 Bglap2 21816 Tgm1 12622 Cer1 19989 Rpl7 12267 C3ar1 67405 Nts 21385 Tbx2 19896 Rpl10a 12279 C9 435337 EG435337 56720 Tdo2 20044 Rps14 12391 Cav3 545913 Zscan4d 16869 Lhx1 19175 Psmb6 12409 Cbr2 244448 Triml1 22253 Unc5c 22627 Ywhae 12477 Ctla4 69134 2200001I15Rik 14174 Fgf3 19951 Rpl32 12523 Cd84 66065 Hsd17b14 16542 Kdr 66152 1110020P15Rik 12524 Cd86 81879 Tcfcp2l1 15122 Hba-a1 66489 Rpl35 12640 Cga 17907 Mylpf 15414 Hoxb6 15519 Hsp90aa1 12642 Ch25h 26424 Nr5a2 210530 Leprel1 66483 Rpl36al 12655 Chi3l3 83560 Tex14 12338 Capn6 27370 Rps26 12796 Camp 17450 Morc1 20671 Sox17 66576 Uqcrh 12869 Cox8b 79455 Pdcl2 20613 Snai1 22154 Tubb5 12959 Cryba4 231821 Centa1 17897 -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

The Biomarkers of Key Mirnas and Target Genes Associated with Acute Myocardial Infarction

The biomarkers of key miRNAs and target genes associated with acute myocardial infarction Qi Wang1, Bingyan Liu2,3, Yuanyong Wang4, Baochen Bai1, Tao Yu3 and Xian–ming Chu1,5 1 Department of Cardiology, The Affiliated hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China 2 School of Basic Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China 3 Institute for Translational Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China 4 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China 5 Department of Cardiology, The Affiliated Cardiovascular Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China ABSTRACT Background. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is considered one of the most prominent causes of death from cardiovascular disease worldwide. Knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying AMI remains limited. Accurate biomarkers are needed to predict the risk of AMI and would be beneficial for managing the incidence rate. The gold standard for the diagnosis of AMI, the cardiac troponin T (cTnT) assay, requires serial testing, and the timing of measurement with respect to symptoms affects the results. As attractive candidate diagnostic biomarkers in AMI, circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) are easily detectable, generally stable and tissue specific. Methods. The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database was used to compare miRNA expression between AMI and control samples, and the interactions between miRNAs and mRNAs were analysed for expression and function. Furthermore, a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed. The miRNAs identified in the bioinformatic analysis were verified by RT-qPCR in an H9C2 cell line. The miRNAs in plasma samples from patients with AMI (n D 11) and healthy controls (n D 11) were used to construct Submitted 23 December 2019 receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to evaluate the clinical prognostic value Accepted 14 April 2020 of the identified miRNAs. -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

SYMPOSIUM References 1

J Orthopaed Traumatol (2008): 24 November 2008 DOI 10.1007/s10195-008-0030-6 24 NOVEMBER 2008 SYMPOSIUM References 1. Pola E, Lattanzi W, Pecorini G, Logroscino CA, Robbins PD (2005) Gene therapy for in vivo bone formation: recent TISSUE ENGINEERING advances. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 9(3):167–174 2. Pola E, Gao W, Zhou Y, Pola R, Lattanzi W, Sfeir C, et al (2004) A CLINICALLY RELEVANT GENE THERAPY APPROACH Efficient bone formation by gene transfer of human LIM miner- TO INDUCE OSTEOGENESIS: STUDY OF THE NEW alization protein-3. Gene Ther 11(8):683 –693 GROWTH FACTOR LIM MINERALIZAZION PROTEIN-3 3. Lattanzi W, Parrilla C, Fetoni A, Logroscino G, Straface G, Pecorini G, Tampieri A, Bedini R, Pecci R, Michetti F, E. Pola Gambotto A, Robbins PD, Pola E (2008) Ex-vivo transduced autologous skin fibroblasts expressing human Lim Minera - Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Università lization Protein-3 efficiently form new bone in animal models. Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, School of Medicine (Rome-IT) Gene Therapy [Epub ahead of print] Recombinant proteins, such as the bone morphogenetic proteins have been used to enhance repair of non-union fractures and facil- TYPE-I COLLAGEN MEMBRANE AS A SCAFFOLD FOR itate new bone formation in animal models as well as in clinical TENDON REPAIR: AN IN VITRO AND IN VIVO STUDY applications. However, a significant amount of recombinant BMP is required to promote osteogenesis and frequently the extent of A. Gigante, E. Cesari, A. Busilacchi, S. Manzotti, F. Greco new bone formation is low. In contrast, local gene transfer of BMPs has been shown to be more efficient in promoting osteogenesis in Department of Orthopaedics, Polytechnic University of Marche rodents than the use of recombinant proteins. -

Impact of a Diet and Activity Health Promotion Intervention on Regional

Hibler et al. Clinical Epigenetics (2019) 11:133 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-019-0707-0 RESEARCH Open Access Impact of a diet and activity health promotion intervention on regional patterns of DNA methylation Elizabeth Hibler1* , Lei Huang2, Jorge Andrade2,3 and Bonnie Spring1 Abstract Background: Studies demonstrate the impact of diet and physical activity on epigenetic biomarkers, specifically DNA methylation. However, no intervention studies have examined the combined impact of dietary and activity changes on the blood epigenome. The objective of this study was to examine the impact of the Make Better Choices 2 (MBC2) healthy diet and activity intervention on patterns of epigenome-wide DNA methylation. The MBC2 study was a 9-month randomized controlled trial among adults aged 18–65 with non-optimal levels of health behaviors. The study compared three 12-week interventions to (1) simultaneously increase exercise and fruit/ vegetable intake, while decreasing sedentary leisure screen time; (2) sequentially increase fruit/vegetable intake and decrease leisure screen time first, then increase exercise; (3) increase sleep and decrease stress (control). We collected blood samples at baseline, 3 and 9 months, and measured DNA methylation using the Illumina EPIC (850 k) BeadChip. We examined region-based differential methylation patterns using linear regression models with the false discovery rate of 0.05. We also conducted pathway analysis using gene ontology (GO), KEGG, and IPA canonical pathway databases. Results: We found no differences between the MBC2 population (n = 340) and the subsample with DNA methylation measured (n = 68) on baseline characteristics or the impact of the intervention on behavior change. -

Individual Protomers of a G Protein-Coupled Receptor Dimer Integrate Distinct Functional Modules

OPEN Citation: Cell Discovery (2015) 1, 15011; doi:10.1038/celldisc.2015.11 © 2015 SIBS, CAS All rights reserved 2056-5968/15 ARTICLE www.nature.com/celldisc Individual protomers of a G protein-coupled receptor dimer integrate distinct functional modules Nathan D Camp1, Kyung-Soon Lee2, Jennifer L Wacker-Mhyre2, Timothy S Kountz2, Ji-Min Park2, Dorathy-Ann Harris2, Marianne Estrada2, Aaron Stewart2, Alejandro Wolf-Yadlin1, Chris Hague2 1Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA; 2Department of Pharmacology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA Recent advances in proteomic technology reveal G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are organized as large, macromolecular protein complexes in cell membranes, adding a new layer of intricacy to GPCR signaling. We previously reported the α1D-adrenergic receptor (ADRA1D)—a key regulator of cardiovascular, urinary and CNS function—binds the syntrophin family of PDZ domain proteins (SNTA, SNTB1, and SNTB2) through a C-terminal PDZ ligand inter- action, ensuring receptor plasma membrane localization and G-protein coupling. To assess the uniqueness of this novel GPCR complex, 23 human GPCRs containing Type I PDZ ligands were subjected to TAP/MS proteomic analysis. Syntrophins did not interact with any other GPCRs. Unexpectedly, a second PDZ domain protein, scribble (SCRIB), was detected in ADRA1D complexes. Biochemical, proteomic, and dynamic mass redistribution analyses indicate syntrophins and SCRIB compete for the PDZ ligand, simultaneously exist within an ADRA1D multimer, and impart divergent pharmacological properties to the complex. Our results reveal an unprecedented modular dimeric architecture for the ADRA1D in the cell membrane, providing unexpected opportunities for fine-tuning receptor function through novel protein interactions in vivo, and for intervening in signal transduction with small molecules that can stabilize or disrupt unique GPCR:PDZ protein interfaces. -

Pharmacogenetics of Response to Neoadjuvant Paclitaxel Treatment for Locally Advanced Breast Cancer

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 63), pp: 106454-106467 Research Paper Pharmacogenetics of response to neoadjuvant paclitaxel treatment for locally advanced breast cancer Andric C. Perez-Ortiz1,2, Israel Ramírez1, Juan C. Cruz-López3,*, Cynthia Villarreal- Garza4,*, Alexandra Luna-Angulo5, Esmeralda Lira-Romero1, Salvador Jiménez- Chaidez1, José Díaz-Chávez6, Juan A. Matus-Santos6, Laura Sánchez-Chapul5, Patricia Mendoza-Lorenzo7 and Francisco J. Estrada-Mena1 1Universidad Panamericana, Escuela de Medicina, Mexico City, Mexico 2Yale University School of Public Health, Laboratory of Epidemiology and Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA 3Hospital Regional ISSSTE Puebla and Hospital General Zona Norte SSEP Puebla, Puebla City, Mexico 4Depto. de Investigacion, Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia, Centro de Cancer de Mama, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico 5Instituto Nacional de Rehabilitación, Mexico City, Mexico 6Unidad de Investigación Biomédica en Cáncer, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas, UNAM/Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Mexico City, Mexico 7División Académica de Ciencias Básicas, Unidad Chontalpa, Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, Tabasco, Mexico *These authors contributed equally to this work Correspondence to: Francisco J. Estrada-Mena, email: [email protected] Keywords: pharmacogenetics; paclitaxel; breast cancer; genetic markers; single nucleotide polymorphism Received: July 27, 2017 Accepted: October 27, 2017 Published: November 15, 2017 Copyright: Perez-Ortiz et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) cases have a varying five-year survival rate, mainly influenced by the tumor response to chemotherapy. -

The Correlation of Keratin Expression with In-Vitro Epithelial Cell Line Differentiation

The correlation of keratin expression with in-vitro epithelial cell line differentiation Deeqo Aden Thesis submitted to the University of London for Degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Supervisors: Professor Ian. C. Mackenzie Professor Farida Fortune Centre for Clinical and Diagnostic Oral Science Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry Queen Mary, University of London 2009 Contents Content pages ……………………………………………………………………......2 Abstract………………………………………………………………………….........6 Acknowledgements and Declaration……………………………………………...…7 List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………8 List of Tables………………………………………………………………………...12 Abbreviations….………………………………………………………………..…...14 Chapter 1: Literature review 16 1.1 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa……………..…………….…..............17 1.2 Maintenance of the oral cavity...……………………………………….................20 1.2.1 Environmental Factors which damage the Oral Mucosa………. ….…………..21 1.3 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa ………………...….……….………...21 1.3.1 Skin Barrier Formation………………………………………………….……...22 1.4 Comparison of Oral Mucosa and Skin…………………………………….……...24 1.5 Developmental and Experimental Models used in Oral mucosa and Skin...……..28 1.6 Keratinocytes…………………………………………………….….....................29 1.6.1 Desmosomes…………………………………………….…...............................29 1.6.2 Hemidesmosomes……………………………………….…...............................30 1.6.3 Tight Junctions………………………….……………….…...............................32 1.6.4 Gap Junctions………………………….……………….….................................32 -

Supplementary Table 1

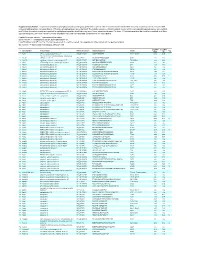

Supplementary Table 1. Large-scale quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling was performed on paired vehicle- and hormone-treated mTAL-enriched suspensions (n=3). A total of 654 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 374 unique phosphoproteins were identified. The peptide sequence, phosphorylation site(s), and the corresponding protein name, gene symbol, and RefSeq Accession number are reported for each phosphopeptide identified in any one of three experimental pairs. For those 414 phosphopeptides that could be quantified in all three experimental pairs, the mean Hormone:Vehicle abundance ratio and corresponding standard error are also reported. Peptide Sequence column: * = phosphorylated residue Site(s) column: ^ = ambiguously assigned phosphorylation site Log2(H/V) Mean and SE columns: H = hormone-treated, V = vehicle-treated, n/a = peptide not observable in all 3 experimental pairs Sig. column: * = significantly changed Log 2(H/V), p<0.05 Log (H/V) Log (H/V) # Gene Symbol Protein Name Refseq Accession Peptide Sequence Site(s) 2 2 Sig. Mean SE 1 Aak1 AP2-associated protein kinase 1 NP_001166921 VGSLT*PPSS*PK T622^, S626^ 0.24 0.95 PREDICTED: ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A 2 Abca12 (ABC1), member 12 XP_237242 GLVQVLS*FFSQVQQQR S251^ 1.24 2.13 3 Abcc10 multidrug resistance-associated protein 7 NP_001101671 LMT*ELLS*GIRVLK T464, S468 -2.68 2.48 4 Abcf1 ATP-binding cassette sub-family F member 1 NP_001103353 QLSVPAS*DEEDEVPVPVPR S109 n/a n/a 5 Ablim1 actin-binding LIM protein 1 NP_001037859 PGSSIPGS*PGHTIYAK S51 -3.55 1.81 6 Ablim1 actin-binding -

Recombinant Human Gamma-1-Syntrophin(SNTG1)

Product Datasheet Recombinant Human Gamma-1-syntrophin(SNTG1) Catalog No: #AP77208 Package Size: #AP77208-1 20ug #AP77208-2 100ug #AP77208-3 500ug Orders: [email protected] Support: [email protected] Description Product Name Recombinant Human Gamma-1-syntrophin(SNTG1) Brief Description Recombinant Protein Host Species Yeast Purification Greater than 90% as determined by SDS-PAGE. Immunogen Description Expression Region:1-517aaSequence Info:Full Length Other Names Syntrophin-4 Accession No. Q9NSN8 Calculated MW 61.5 kDa Tag Info N-terminal 6xHis-tagged and C-terminal Myc-tagged Target Sequence MDFRTACEETKTGICLLQDGNQEPFKVRLHLAKDILMIQEQDVICVSGEPFYSGERTVTIRRQTVGGFGLSIKG GAEHNIPVVVSKISKEQRAELSGLLFIGDAILQINGINVRKCRHEEVVQVLRNAGEEVTLTVSFLKRAPAFLKLPL NEDCACAPSDQSSGTSSPLCDSGLHLNYHPNNTDTLSCSSWPTSPGLRWEKRWCDLRLIPLLHSRFSQYVP GTDLSRQNAFQVIAVDGVCTGIIQCLSAEDCVDWLQAIATNISNLTKHNIKKINRNFPVNQQIVYMGWCEAREQ DPLQDRVYSPTFLALRGSCLYKFLAPPVTTWDWTRAEKTFSVYEIMCKILKDSDLLDRRKQCFTVQSESGEDL YFSVELESDLAQWERAFQTATFLEVERIQCKTYACVLESHLMGLTIDFSTGFICFDAATKAVLWRYKFSQLKGS SDDGKSKIKFLFQNPDTKQIEAKELEFSNLFAVLHCIHSFFAAKVACLDPLFLGNQATASTAASSATTSKAKYTT Formulation Tris-based buffer50% glycerol Storage The shelf life is related to many factors, storage state, buffer ingredients, storage temperature and the stability of the protein itself. Generally, the shelf life of liquid form is 6 months at -20°C,-80°C. The shelf life of lyophilized form is 12 months at -20°C,-80°C.Notes:Repeated freezing and thawing is not recommended. Store working aliquots at 4°C for up to