As Cultural Performance in Chinese: Cases of Requesting and Declining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

Adaptive Fuzzy Pid Controller's Application in Constant Pressure Water Supply System

2010 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2010) Hangzhou, China 4-6 December 2010 Pages 1-774 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1076H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-7616-9 1 / 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADAPTIVE FUZZY PID CONTROLLER'S APPLICATION IN CONSTANT PRESSURE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Xiao Zhi-Huai, Cao Yu ZengBing APPLICATION OF OPC INTERFACE TECHNOLOGY IN SHEARER REMOTE MONITORING SYSTEM ...............................5 Ke Niu, Zhongbin Wang, Jun Liu, Wenchuan Zhu PASSIVITY-BASED CONTROL STRATEGIES OF DOUBLY FED INDUCTION WIND POWER GENERATOR SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................................................................................9 Qian Ping, Xu Bing EXECUTIVE CONTROL OF MULTI-CHANNEL OPERATION IN SEISMIC DATA PROCESSING SYSTEM..........................14 Li Tao, Hu Guangmin, Zhao Taiyin, Li Lei URBAN VEGETATION COVERAGE INFORMATION EXTRACTION BASED ON IMPROVED LINEAR SPECTRAL MIXTURE MODE.....................................................................................................................................................................18 GUO Zhi-qiang, PENG Dao-li, WU Jian, GUO Zhi-qiang ECOLOGICAL RISKS ASSESSMENTS OF HEAVY METAL CONTAMINATIONS IN THE YANCHENG RED-CROWN CRANE NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE BY SUPPORT -

Tsld.Tm Jjjjljjj . . Js. . .

Dejan An tic & Branimir Maksimovic The Mod ern Bogo 1.d4 e6 A Com plete Guide for Black New In Chess 2014 Con tents Fore word ....................................................7 Part I: 3.Ãd2 .................................................9 Sec tion I The Exchange 3...Ãxd2+ ..........................11 Chap ter 1 The Side line 4.Àxd2 ............................12 Chapter 2 Black Fianchetto: 4.©xd2 Àf6 5.Àf3 b6 .............21 Chap ter 2.1 Cen tral Strat egy: 6.Àc3 ..........................22 Chap ter 2.2 Fianchetto 6.g3 ................................28 Chapter 3 5...0-0 .......................................57 Chap ter 3.1 Fianchetto 6.g3 ................................58 Chap ter 3.2 Cen tral Strat egy: 6.Àc3 ..........................63 Chap ter 4 The Clas si cal Cen tre – 4.©xd2 Àf6 5.Àf3 d5: The Fianchetto 6.g3.............................69 Chap ter 4.1 Black Plays in the Cen tre with ...©e7 ................70 Chap ter 4.2 The Black Queenside Fianchetto....................77 Chapter 5 White Builds the Cen tre ..........................97 Chap ter 5.1 The Flexi ble 7...Àbd7 ...........................98 Chap ter 5.2 7...©e7: Main Line 8.Õc1 .......................113 Chap ter 5.3 7...©e7: Re leas ing the Ten sion – 8.cxd5 ............129 Sec tion II The 3...c5 Sys tem: 3...c5 4.Ãxb4 cxb4 5.Àf3 Àf6 ....139 Chap ter 6 The Early 6.Àbd2 .............................140 Chapter 7 The Sta ble Cen tre: 6.e3 .........................149 Chapter 8 Play on the Queenside: 6.a3......................160 Chap ter 9 The Fianchetto: 6.g3 -

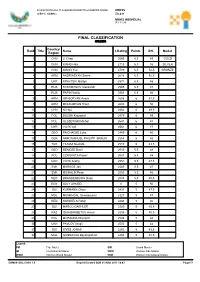

Final Classification 单项成绩单

PLUM BLOSSOM HALL OF SHENZHEN CONVENTION & EXHIBITION CENTER CHESS 会展中心 5楼梅花厅 国际象棋 MEN'S INDIVIDUAL 男子个人赛 FINAL CLASSIFICATION 单项成绩单 Country/ Rank Title Name I.Rating Points BH. Medal Region 1 CHN LI Chao 2669 8.5 49 GOLD 2 CHN WANG Hao 2718 6.5 55 SILVER 3 CHN WANG Yue 2709 6.5 52.5 BRONZE 4 ARM ANDRIASYAN Zaven 2616 6.5 52.5 5 UKR KRAVTSIV Martyn 2571 6.5 48 6 RUS RAKHMANOV Aleksandr 2585 6.5 47 7 RUS PAPIN Vasily 2565 6.5 46 8 ARM GRIGORYAN Avetik 2608 6 51.5 9 ARM MELKUMYAN Hrant 2600 6 50 10 CHN NI Hua 2662 6 49.5 11 POL BULSKI Krzysztof 2479 6 49 12 POL OLSZEWSKI Michal 2541 6 47 13 UKR VOVK Iurii 2564 6 47 14 GEO PAICHADZE Luka 2489 6 46 15 GER ARIK IMANUEL PHILIPP BRAUN 2554 6 46 16 TUR YILMAZ Mustafa 2519 6 43.5 17 GEO BENIDZE Davit 2514 5.5 48 18 POL CZARNOTA Pawel 2541 5.5 48 19 UKR VOVK Andriy 2551 5.5 47.5 20 SVK MARKOS Jan 2585 5.5 47 21 SVK MICHALIK Peter 2505 5.5 45 22 NED BRANDENBURG Daan 2538 5.5 40.5 23 EGY ADLY AHMED 0 5 50 24 SUI KURMANN Oliver 2431 5 47.5 25 MGL MUNKHGAL Gombosuren 2327 5 47 26 NED SWINKELS Robin 2483 5 46 27 SUI MARCO GAEHLER 2320 5 45.5 28 KAZ ISMAGAMBETOV Anuar 2505 5 45.5 29 POL MORANDA Wojciech 2586 5 44 30 UKR PAVLOV Sergii 2505 5 44 31 SUI WYSS JONAS 2292 5 43.5 32 MGL GUNDAVAA Bayarsaikhan 2480 5 42.5 Legend: FM Fide Mater GM Grand Master IM International Master WFM Women Fide Master WGM Women Grand Master WIM Women International Master CHM001000_C96A 1.0 Report Created SUN 21 AUG 2011 14:43 Page1/3 PLUM BLOSSOM HALL OF SHENZHEN CONVENTION & EXHIBITION CENTER CHESS 会展中心 5楼梅花厅 国际象棋 MEN'S INDIVIDUAL 男子个人赛 FINAL CLASSIFICATION 单项成绩单 Country/ Rank Title Name I.Rating Points BH. -

The Earliest Muslim Communities in China

8 The Earliest Muslim Communities in China February - March 2017 Jumada I - Rajab, 1438 WAN Lei Research Fellow King Faisal Center For Research and Islamic Studies The Earliest Muslim Communities in China WAN Lei Research Fellow King Faisal Center For Research and Islamic Studies No. 8 Jumada I - Rajab, 1438 - February - March 2017 © King Faisal Center for research and Islamic Studies, 2016 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-In-Publication Data Lei, Wan The earliest Muslim communities in China, / Wan Lei, - Riyadh, 2017 42 p; 16.5x23cm ISBN: 978-603-8206-39-3 1- Muslims - China 2- Muslims - China - History I- Title 210.9151 dc 1439/1181 L.D. no. 1439/1181 ISBN: 978-603-8206-39-3 4 Table of Contents Abstract 6 I. Background on Muslim Immigration to China 7 II. Designating Alien people in China: from “Hu” to “Fan” 11 III. Chinese Titles for Muslim Chiefs 17 IV. Duties of Muslim Community Chiefs 21 V. Challenges to “Extraterritoriality” and Beyond 27 Summaries 32 Bibliography 34 5 No. 8 Jumada I - Rajab, 1438 - February - March 2017 Abstract This article explores the earliest Muslim immigration into China during the Tang and Song dynasties. The background of such immigration, along with various Chinese titles to designate Muslims, their communities, and their leaders demonstrate the earliest forms of recognition of the Muslims by the Chinese people. The article focuses on the studies of the Muslim leaders’ duties and their confrontations with the Chinese legal system; to adapt to a new society, a community must undergo acculturation. Finally, the system of Muslim leaders was improved by the succeeding Mongol Yuan dynasty, by which time it became an established tradition that has been passed on by the Hui people until today. -

Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Gregory Adam Scott All Rights Reserved This work may be used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. For more information about that license, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. For other uses, please contact the author. ABSTRACT Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China 經典佛化: 民國初期佛教出版文化 Gregory Adam Scott 史瑞戈 In this dissertation I argue that print culture acted as a catalyst for change among Buddhists in modern China. Through examining major publication institutions, publishing projects, and their managers and contributors from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s, I show that the expansion of the scope and variety of printed works, as well as new the social structures surrounding publishing, substantially impacted the activity of Chinese Buddhists. In doing so I hope to contribute to ongoing discussions of the ‘revival’ of Chinese Buddhism in the modern period, and demonstrate that publishing, propelled by new print technologies and new forms of social organization, was a key field of interaction and communication for religious actors during this era, one that helped make possible the introduction and adoption of new forms of religious thought and practice. 本論文的論點是出版文化在近代中國佛教人物之中,扮演了變化觸媒的角色. 通過研究從十 九世紀末到二十世紀二十年代的主要的出版機構, 種類, 及其主辦人物與提供貢獻者, 論文 說明佛教印刷的多元化 以及範圍的大量擴展, 再加上跟出版有關的社會結構, 對中國佛教 人物的活動都發生了顯著的影響. 此研究顯示在被新印刷技術與新形式的社會結構的推進 下的出版事業, 為該時代的宗教人物展開一種新的相互連結與構通的場域, 因而使新的宗教 思想與實踐的引入成為可能. 此論文試圖對現行關於近代中國佛教的所謂'復興'的討論提出 貢獻. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations and Conventions ix Works Cited by Abbreviation x Maps of Principle Locations xi Introduction Print Culture and Religion in Modern China 1. -

Emirate of UAE with More Than Thirty Years of Chess Organizational Experience

DUBAI Emirate of UAE with more than thirty years of chess organizational experience. Many regional, continental and worldwide tournaments have been organized since the year 1985: The World Junior Chess Championship in Sharjah, UAE won by Max Dlugy in 1985, then the 1986 Chess Olympiad in Dubai won by USSR, the Asian Team Chess Championship won by the Philippines. Dubai hosted also the Asian Cities Championships in 1990, 1992 and 1996, the FIDE Grand Prix (Rapid, knock out) in 2002, the Arab Individual Championship in 1984, 1992 and 2004, and the World Blitz & Rapid Chess Championship 2014. Dubai Chess & Culture Club is established in 1979, as a member of the UAE Chess Federation and was proclaimed on 3/7/1981 by the Higher Council for Sports & Youth. It was first located in its previous premises in Deira–Dubai as a temporarily location for the new building to be over. Since its launching, the Dubai Chess & Culture Club has played a leading role in the chess activity in UAE, achieving for the country many successes on the international, continental and Arab levels. The Club has also played an imminent role through its administrative members who contributed in promoting chess and leading the chess activity along with their chess colleagues throughout UAE. “Sheikh Rashid Bin Hamdan Al Maktoum Cup” The Dubai Open championship, the SHEIKH RASHID BIN HAMDAN BIN RASHID AL MAKTOUM CUP, the strongest tournament in Arabic countries for many years, has been organized annually as an Open Festival since 1999, it attracts every year over 200 participants. Among the winners are Shakhriyar Mamedyarov (in the edition when Magnus Carlsen made his third and final GM norm at the Dubai Open of 2004), Wang Hao, Wesley So, or Gawain Jones. -

Box Hill and Canterbury Chess News

CJCC ABN 52 352 957 553 BHCC ABN 52 929 596 514 Date: 03 Feb, 2015 Volume 6 issue 03 Box Hill and Canterbury Chess News Page In This Issue Calendar 1 Calendar www.boxhillchess.org.au/calendar/ 1 Editorial 2 Venue Update 3 Billanook College Scholarships Date Day Time Event Feb 06 Friday 7:30pm Autumn Cup 2 3 Financial members Feb 08 Sunday 12:30pm Rookies Cup 4 Game Of The Week by Laurence Matheson Feb 13 Friday 7:30pm Autumn Cup 3 5 Our Sponsors, Bits & Pieces Feb 15 Sunday 2pm Coaching 6 IM Max Illingworth–Australian Juniors 3:45pm Sunday Arvo Swiss 9 AJCC 2015 – Photo montage – CJCC winners Feb 20 Friday 7:30pm Autumn Cup 4 10 Northern Star Chess Cards Feb 22 Sunday 2pm Coaching 11 Forthcoming Events - Autumn Cup, 3:45pm Sunday Arvo Swiss 11 Sunday Arvo Swiss Feb 27 Friday 7:30pm Autumn Cup 5 Mar 01 Sunday 2pm Coaching 12 February Rookies 3:45pm Sunday Arvo Swiss 12 CJCC Group Coaching Details Mar 06 Friday 7:30pm Allegro 13 A visit to Katoomba Chess Club Mar 08 Sunday 12:30pm Rookies Cup 13 Sunday Coaching Mar 13 Friday 7:30pm Autumn Cup 6 13 Sunday ARVO Mar 15 Sunday 2pm Coaching 14 Autumn Cup 3:45pm Sunday Arvo Swiss 14 Marcus’s Book Shop 15 GM Ni Hua Simul Report. 17 Australian Junior Chess League How to subscribe to the Box Hill and Editorial Canterbury Chess News The quality and content of this newsletter is very much Box Hill and Canterbury Chess News is dependent on the contributions of members. -

China As an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20Th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni

China as an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni 1 China as an Issue is an ongoing lecture series orga- nized by the Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum since 2018. Chinese scholars are invited to discuss topics related to China or the world, as well as foreign schol- ars to speak about China or international questions in- volving the subject of China. Through rigorous scruti- nization of a specific issue we try to avoid making generalizations as well as the parochial tendency to reject extraterritorial or foreign theories in the study of domestic issues. The attempt made here is not only to see the world from a local Chinese perspective, but also to observe China from a global perspective. By calling into question the underlying typology of the inside and the outside we consider China as an issue requiring discussion, rather than already having an es- tablished premise. By inviting fellow thinkers from a wide range of disciplines to discuss these topics we were able to negotiate and push the parameters of art and stimulate a discourse that intersects the arts with other discursive fields. The idea to publish the first volume of China as An Issue was initiated before the rampage of the coron- avirus pandemic. When the virus was prefixed with “China,” we also had doubts about such self-titling of ours. However, after some struggles and considera- tion, we have increasingly found the importance of 2 discussing specific viewpoints and of clarifying and discerning the specific historical, social, cultural and political situations the narrator is in and how this helps us avoid discussions that lack direction or substance. -

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年8月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年8月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年8月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Lu An, CMA 2018 57482 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Mating-Induced Male Death and Pheromone Toxin-Regulated Androstasis

bioRxiv preprint first posted online Dec. 15, 2015; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/034181. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not peer-reviewed) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Shi, Runnels & Murphy – preprint version –www.biorxiv.org Mating-induced Male Death and Pheromone Toxin-regulated Androstasis Cheng Shi, Alexi M. Runnels, and Coleen T. Murphy* Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics and Dept. of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA *Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract How mating affects male lifespan is poorly understood. Using single worm lifespan assays, we discovered that males live significantly shorter after mating in both androdioecious (male and hermaphroditic) and gonochoristic (male and female) Caenorhabditis. Germline-dependent shrinking, glycogen loss, and ectopic expression of vitellogenins contribute to male post-mating lifespan reduction, which is conserved between the sexes. In addition to mating-induced lifespan decrease, worms are subject to killing by male pheromone-dependent toxicity. C. elegans males are the most sensitive, whereas C. remanei are immune, suggesting that males in androdioecious and gonochoristic species utilize male pheromone differently as a toxin or a chemical messenger. Our study reveals two mechanisms involved in male lifespan regulation: germline-dependent shrinking and death is the result of an unavoidable cost of reproduction and is evolutionarily conserved, whereas male pheromone-mediated killing provides a novel mechanism to cull the male population and ensure a return to the self-reproduction mode in androdioecious species. Our work highlights the importance of understanding the shared vs. sex- and species- specific mechanisms that regulate lifespan.