Kabuki Syndrome: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Nr: 1 from the 2004 ASHG Annual Meeting Mutations in A

Program Nr: 1 from the 2004 ASHG Annual Meeting Mutations in a novel member of the chromodomain gene family cause CHARGE syndrome. L.E.L.M. Vissers1, C.M.A. van Ravenswaaij1, R. Admiraal2, J.A. Hurst3, B.B.A. de Vries1, I.M. Janssen1, W.A. van der Vliet1, E.H.L.P.G. Huys1, P.J. de Jong4, B.C.J. Hamel1, E.F.P.M. Schoenmakers1, H.G. Brunner1, A. Geurts van Kessel1, J.A. Veltman1. 1) Dept Human Genetics, UMC Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands; 2) Dept Otorhinolaryngology, UMC Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands; 3) Dept Clinical Genetics, The Churchill Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom; 4) Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, BACPAC Resources, Oakland, CA. CHARGE association denotes the non-random occurrence of ocular coloboma, heart defects, choanal atresia, retarded growth and development, genital hypoplasia, ear anomalies and deafness (OMIM #214800). Almost all patients with CHARGE association are sporadic and its cause was unknown. We and others hypothesized that CHARGE association is due to a genomic microdeletion or to a mutation in a gene affecting early embryonic development. In this study array- based comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) was used to screen patients with CHARGE association for submicroscopic DNA copy number alterations. De novo overlapping microdeletions in 8q12 were identified in two patients on a genome-wide 1 Mb resolution BAC array. A 2.3 Mb region of deletion overlap was defined using a tiling resolution chromosome 8 microarray. Sequence analysis of genes residing within this critical region revealed mutations in the CHD7 gene in 10 of the 17 CHARGE patients without microdeletions, including 7 heterozygous stop-codon mutations. -

Kabuki Syndrome

Kabuki syndrome Description Kabuki syndrome is a disorder that affects many parts of the body. It is characterized by distinctive facial features including arched eyebrows; long eyelashes; long openings of the eyelids (long palpebral fissures) with the lower lids turned out (everted) at the outside edges; a flat, broadened tip of the nose; and large protruding earlobes. The name of this disorder comes from the resemblance of its characteristic facial appearance to stage makeup used in traditional Japanese Kabuki theater. People with Kabuki syndrome have mild to severe developmental delay and intellectual disability. Affected individuals may also have seizures, an unusually small head size ( microcephaly), or weak muscle tone (hypotonia). Some have eye problems such as rapid, involuntary eye movements (nystagmus) or eyes that do not look in the same direction (strabismus). Other characteristic features of Kabuki syndrome include short stature and skeletal abnormalities such as abnormal side-to-side curvature of the spine (scoliosis), short fifth (pinky) fingers, or problems with the hip and knee joints. The roof of the mouth may have an abnormal opening (cleft palate) or be high and arched, and dental problems are common in affected individuals. People with Kabuki syndrome may also have fingerprints with unusual features and fleshy pads at the tips of the fingers. These prominent finger pads are called fetal finger pads because they normally occur in human fetuses; in most people they disappear before birth. A wide variety of other health problems occur in some people with Kabuki syndrome. Among the most commonly reported are heart abnormalities, frequent ear infections ( otitis media), hearing loss, and early puberty. -

MECHANISMS in ENDOCRINOLOGY: Novel Genetic Causes of Short Stature

J M Wit and others Genetics of short stature 174:4 R145–R173 Review MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY Novel genetic causes of short stature 1 1 2 2 Jan M Wit , Wilma Oostdijk , Monique Losekoot , Hermine A van Duyvenvoorde , Correspondence Claudia A L Ruivenkamp2 and Sarina G Kant2 should be addressed to J M Wit Departments of 1Paediatrics and 2Clinical Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center, PO Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, Email The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract The fast technological development, particularly single nucleotide polymorphism array, array-comparative genomic hybridization, and whole exome sequencing, has led to the discovery of many novel genetic causes of growth failure. In this review we discuss a selection of these, according to a diagnostic classification centred on the epiphyseal growth plate. We successively discuss disorders in hormone signalling, paracrine factors, matrix molecules, intracellular pathways, and fundamental cellular processes, followed by chromosomal aberrations including copy number variants (CNVs) and imprinting disorders associated with short stature. Many novel causes of GH deficiency (GHD) as part of combined pituitary hormone deficiency have been uncovered. The most frequent genetic causes of isolated GHD are GH1 and GHRHR defects, but several novel causes have recently been found, such as GHSR, RNPC3, and IFT172 mutations. Besides well-defined causes of GH insensitivity (GHR, STAT5B, IGFALS, IGF1 defects), disorders of NFkB signalling, STAT3 and IGF2 have recently been discovered. Heterozygous IGF1R defects are a relatively frequent cause of prenatal and postnatal growth retardation. TRHA mutations cause a syndromic form of short stature with elevated T3/T4 ratio. Disorders of signalling of various paracrine factors (FGFs, BMPs, WNTs, PTHrP/IHH, and CNP/NPR2) or genetic defects affecting cartilage extracellular matrix usually cause disproportionate short stature. -

Hereditary Interstitial Lung Diseases Manifesting in Early Childhood in Japan

nature publishing group Clinical Investigation Articles Hereditary interstitial lung diseases manifesting in early childhood in Japan Takuma Akimoto1, Kazutoshi Cho1, Itaru Hayasaka1, Keita Morioka1, Yosuke Kaneshi1, Itsuko Furuta2, Masafumi Yamada3, Tadashi Ariga3 and Hisanori Minakami2 BACKGROUND: Genetic variations associated with intersti- (SP)-B deficiency (1), SP-C abnormality (2), and ATP-binding tial lung diseases (ILD) have not been extensively studied in cassette A3 (ABCA3) deficiency (3). Disorder of alveolar mac- Japanese infants. rophages includes abnormality in granulocyte macrophage METHODS: Forty-three infants with unexplained lung dys- colony–stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor (4,5) and dys- function were studied. All 43, 22, and 17 infants underwent function of macrophages associated with hypogammaglobu- analyses of surfactant protein (SP)-C gene (SFTPC) and ATP- linemia (6). Although considerable overlapping exists, genetic binding cassette A3 gene (ABCA3), SP-B gene (SFTPB), and disorders of SP-B and alveolar macrophages are likely to mani- SP-B western blotting, respectively. Two and four underwent fest hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP), while assessment of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating those of SP-C and ABCA3 are likely to manifest hPAP and/or factor–stimulating phosphorylation of signal transducer and interstitial pneumonitis (7). In addition, genetic disorders of activator of transcription-5 (pSTAT-5) and analyses of FOXF1 thyroid transcription factor-1–associated thyroid dysfunction gene (FOXF1), respectively. (8) and alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pul- RESULTS: ILD were diagnosed clinically in nine infants: four, monary veins (ACD/MPV) (9) often manifest interstitial lung three, and two had interstitial pneumonitis, hereditary pul- disease (ILD) in early childhood. -

X-Linked Diseases: Susceptible Females

REVIEW ARTICLE X-linked diseases: susceptible females Barbara R. Migeon, MD 1 The role of X-inactivation is often ignored as a prime cause of sex data include reasons why women are often protected from the differences in disease. Yet, the way males and females express their deleterious variants carried on their X chromosome, and the factors X-linked genes has a major role in the dissimilar phenotypes that that render women susceptible in some instances. underlie many rare and common disorders, such as intellectual deficiency, epilepsy, congenital abnormalities, and diseases of the Genetics in Medicine (2020) 22:1156–1174; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436- heart, blood, skin, muscle, and bones. Summarized here are many 020-0779-4 examples of the different presentations in males and females. Other INTRODUCTION SEX DIFFERENCES ARE DUE TO X-INACTIVATION Sex differences in human disease are usually attributed to The sex differences in the effect of X-linked pathologic variants sex specific life experiences, and sex hormones that is due to our method of X chromosome dosage compensation, influence the function of susceptible genes throughout the called X-inactivation;9 humans and most placental mammals – genome.1 5 Such factors do account for some dissimilarities. compensate for the sex difference in number of X chromosomes However, a major cause of sex-determined expression of (that is, XX females versus XY males) by transcribing only one disease has to do with differences in how males and females of the two female X chromosomes. X-inactivation silences all X transcribe their gene-rich human X chromosomes, which is chromosomes but one; therefore, both males and females have a often underappreciated as a cause of sex differences in single active X.10,11 disease.6 Males are the usual ones affected by X-linked For 46 XY males, that X is the only one they have; it always pathogenic variants.6 Females are biologically superior; a comes from their mother, as fathers contribute their Y female usually has no disease, or much less severe disease chromosome. -

Blueprint Genetics Congenital Structural Heart Disease Panel

Congenital Structural Heart Disease Panel Test code: CA1501 Is a 114 gene panel that includes assessment of non-coding variants. Is ideal for patients with congenital heart disease, particularly those with features of hereditary disorders. Is not ideal for patients suspected to have a ciliopathy or a rasopathy. For those patients, please consider our Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Panel and our Noonan Syndrome Panel, respectively. About Congenital Structural Heart Disease There are many types of congenital heart disease (CHD) ranging from simple asymptomatic defects to complex defects with severe, life-threatening symptoms. CHDs are the most common type of birth defect and affect at least 8 out of every 1,000 newborns. Annually, more than 35,000 babies in the United States are born with CHDs. Many of these CHDs are simple conditions and need no treatment or are easily repaired. Some babies are born with complex CHD requiring special medical care. The diagnosis and treatment of complex CHDs has greatly improved over the past few decades. As a result, almost all children who have complex heart defects survive to adulthood and can live active, productive lives. However, many patients who have complex CHDs continue to need special heart care throughout their lives. In the United States, more than 1 million adults are living with congenital heart disease. Availability 4 weeks Gene Set Description Genes in the Congenital Structural Heart Disease Panel and their clinical significance Gene Associated phenotypes Inheritance ClinVar HGMD ABL1 Congenital -

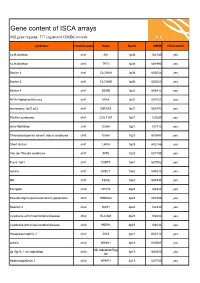

ISCA Disease List

Gene content of ISCA arrays 402 gene regions, 377 registered OMIM records syndrome chromosome Gene Band OMIM ISCA 8x60k 1p36 deletion chr1 SKI 1p36 164780 yes 1p36 deletion chr1 TP73 1p36 601990 yes Bartter 4 chr1 CLCNKA 1p36 602024 yes Bartter 3 chr1 CLCNKB 1p36 602023 yes Bartter 4 chr1 BSND 1p32 606412 yes NFIA Haploinsufficiency chr1 NFIA 1p31 600727 yes monosomy 1p31 p22 chr1 DIRAS3 1p31 605193 yes Stickler syndrome chr1 COL11A1 1p21 120280 yes atrial fibrillation chr1 GJA5 1q21 121013 yes Thrombocytopenia absent radius syndrome chr1 GJA8 1q21 600897 yes Short stature chr1 LHX4 1q25 602146 yes Van der Woude syndrome chr1 IRF6 1q32 607199 yes Fryns 1q41 chr1 DISP1 1q41 607502 yes autism chr1 DISC1 1q42 605210 yes MR chr1 TBCE 1q42 604934 yes Feingold chr2 MYCN 2q24 164840 yes Pseudovaginal perineoscrotal hypospadias chr2 SRD5A2 2p23 607306 yes Noonan 4 chr2 SOS1 2p22 182530 yes Cystinuria with mitochondrial disease chr2 SLC3A1 2p21 104614 yes Cystinuria with mitochondrial disease chr2 PREPL 2p21 104614 yes Holopresencaphly 2 chr2 SIX3 2p21 603714 yes autism chr2 NRXN1 2p16 600565 yes MicrodeletionReg 2p15p16.1 microdeletion chr2 2p15 602559 yes ion Nephronophthsis 1 chr2 NPHP1 2q13 607100 yes Holoprosencephaly 9 chr2 GLI2 2q14 165230 yes visceral heterotaxy chr2 CFC1 2q21 605194 yes Mowat-Wilson syndrome chr2 ZEB2 2q22 605802 yes autism chr2 SLC4A10 2q24 605556 yes SCN1A-related seizures chr2 SCN1A 2q24 182389 yes HYPOMYELINATION, GLOBAL CEREBRAL chr2 SLC25A12 2q31 603667 yes Split/hand foot malformation -5 chr2 DLX1 2q31 600029 yes -

Neurology, Neuromuscular, and Cardiology Disorders

GENETIC TESTING SOLUTIONS FOR: NEUROLOGY, NEUROMUSCULAR, AND CARDIOLOGY DISORDERS EGL Genetics has nearly 50 years of genetic testing history built upon a strong academic foundation. Our expertise spans common and rare genetic disease testing, genomic variant interpretation, test development and research. As we have grown, we have evolved into a high-science and high-performing CLIA-certifi ed and CAP-accredited laboratory with over 1,100 test offerings across biochemical genetics, cytogenetics, and molecular genetic testing. COMPREHENSIVE OFFERINGS There are signifi cant genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity for disorders involving neurology, neuromuscular, and cardiovascular systems, and obtaining a specifi c diagnosis is important for prognosis, patient management, and development of therapeutic strategies. Consider this collection of test offerings for patients with heart disease, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, movement disorders, epilepsy, and more. Identifi cation of a causative genetic defect may provide information for prognosis and therapeutic intervention, and is required for carrier testing and early prenatal diagnosis. TEST OFFERINGS FOR THE FOLLOWING CLINICAL INDICATIONS: • Cardiomyopathy and cardiovascular diseases • Autism and intellectual disabilities • Neuromuscular disorders and muscular dystrophy • Epilepsy • Movement disorders ADVANTAGES OF PARTNERING WITH EGL GENETICS: • Board-certifi ed laboratory directors & genetic counselors to answer clinical and analytical questions • Multiple sample collection -

ORD Resources Report

Resources and their URL's 12/1/2013 Resource Name: Resource URL: 1 in 9: The Long Island Breast Cancer Action Coalition http://www.1in9.org 11q Research and Resource Group http://www.11qusa.org 1p36 Deletion Support & Awareness http://www.1p36dsa.org 22q11 Ireland http://www.22q11ireland.org 22qcentral.org http://22qcentral.org 2q23.org http://2q23.org/ 4p- Support Group http://www.4p-supportgroup.org/ 4th Angel Mentoring Program http://www.4thangel.org 5p- Society http://www.fivepminus.org A Foundation Building Strength http://www.buildingstrength.org A National Support group for Arthrogryposis Multiplex http://www.avenuesforamc.com Congenita (AVENUES) A Place to Remember http://www.aplacetoremember.com/ Aarons Ohtahara http://www.ohtahara.org/ About Special Kids http://www.aboutspecialkids.org/ AboutFace International http://aboutface.ca/ AboutFace USA http://www.aboutfaceusa.org Accelerate Brain Cancer Cure http://www.abc2.org Accelerated Cure Project for Multiple Sclerosis http://www.acceleratedcure.org Accord Alliance http://www.accordalliance.org/ Achalasia 101 http://achalasia.us/ Acid Maltase Deficiency Association (AMDA) http://www.amda-pompe.org Acoustic Neuroma Association http://anausa.org/ Addison's Disease Self Help Group http://www.addisons.org.uk/ Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Organization International http://www.accoi.org/ Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Foundation http://www.accrf.org/ Advocacy for Neuroacanthocytosis Patients http://www.naadvocacy.org Advocacy for Patients with Chronic Illness, Inc. http://www.advocacyforpatients.org -

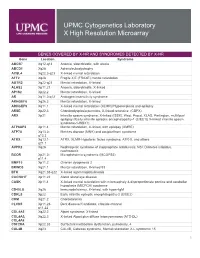

Genes Covered and Disorders Detected by X-HR Microarray

UPMC Cytogenetics Laboratory X High Resolution Microarray GENES COVERED BY X-HR AND SYNDROMES DETECTED BY X-HR Gene Location Syndrome ABCB7 Xq12-q13 Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia ABCD1 Xq28 Adrenoleukodystrophy ACSL4 Xq22.3-q23 X-linked mental retardation AFF2 Xq28 Fragile X E (FRAXE) mental retardation AGTR2 Xq22-q23 Mental retardation, X-linked ALAS2 Xp11.21 Anemia, sideroblastic, X-linked AP1S2 Xp22.2 Mental retardation, X-linked AR Xq11.2-q12 Androgen insensitivity syndrome ARHGEF6 Xq26.3 Mental retardation, X-linked ARHGEF9 Xq11.1 X-linked mental retardation (XLMR)//Hyperekplexia and epilepsy ARSE Xp22.3 Chondrodysplasia punctata, X-linked recessive (CDPX) ARX Xp21 Infantile spasm syndrome, X-linked (ISSX), West, Proud, XLAG, Partington, multifocal epilepsy //Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-1 (EIEE1)( X-linked infantile spasm syndrome-1-ISSX1) ATP6AP2 Xp11.4 Mental retardation, X-linked, with epilepsy (XMRE) ATP7A Xq13.2- Menkes disease (MNK) and occipital horn syndrome q13.3 ATRX Xq13.1- ATRX, XLMR-Hypotonic facies syndrome, ATR-X, and others q21.1 AVPR2 Xq28 Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis; NSI; Diabetes insipidus, nephrogenic BCOR Xp21.2- Microphthalmia syndromic (MCOPS2) p11.4 BMP15 Xp11.2 Ovarian dysgenesis 2 BRWD3 Xq21.1 Mental retardation, X-linked 93 BTK Xq21.33-q22 X-linked agammaglobulinemia CACNA1F Xp11.23 Aland Island eye disease CASK Xp11.4 X-linked mental retardation with microcephaly & disproportionate pontine and cerebellar hypoplasia (MICPCH) syndrome CD40LG Xq26 Immunodeficiency, -

Phenotypic and Genotypic Features of Familial Hypodontia

Institute of Dentistry, Department of Pedodontics and Orthodontics, University of Helsinki, Finland Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Diseases, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki PHENOTYPIC AND GENOTYPIC FEATURES OF FAMILIAL HYPODONTIA Sirpa Arte Academic Dissertation to be publicly discussed with the permission of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Helsinki in the Main Auditorium of the Institute of Dentistry on 19 October, 2001, at 12 noon. Helsinki 2001 1b216251taitto28.9 1 28.9.2001, 17:49 Supervised by Sinikka Pirinen, DDS, PhD Professor Department of Pedodontics and Orthodontics Institute of Dentistry, University of Helsinki, Finland Irma Thesleff, DDS, PhD Professor Developmental Biology Programme Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Finland Reviewed by Mirja Somer, MD, PhD Docent Department of Medical Genetics University of Helsinki and Clinical Genetics Unit Helsinki University Central Hospital, Finland Birgitta Bäckman, DDS, PhD Associate Professor Department of Odontology/Pedodontics Faculty of Medicine and Odontology University of Umeå, Sweden ISBN 952-91-3894-6 (Print) ISBN 952-10-0154-2 (PDF) Yliopistopaino Helsinki 2001 1b216251taitto28.9 2 28.9.2001, 17:49 To Lauri, Eero, and Elisa 1b216251taitto28.9 3 28.9.2001, 17:49 4 1b216251taitto28.9 4 28.9.2001, 17:49 CONTENTS LIST OF ORIGINAL PUBLICATIONS ................................................................. 9 ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................................... 10 -

Pediatric Orthopedics in Practice, DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-46810-4, © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 880 Backmatter

879 Backmatter Subject Index – 880 F. Hefti, Pediatric Orthopedics in Practice, DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-46810-4, © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 880 Backmatter Subject index Bold letters: Principal article Italics: Illustrations A Acetylsalicylic acid 303, 335 Adolescent scoliosis Amyloidosis 663 Acheiropodia 804 7 Scoliosis Amyoplasia 813–814 Abducent nerve paresis 752, Achievement by proxy 10, 11 AFO 7 Ankle Foot Orthosis Anaerobes 649, 652, 657 816 Achilles tendon Aggrecan 336, 367, 762 ANA 7 antinuclear antibodies Abducted pes planovalgus – lengthening 371, 426, 431, aggressive osteomyelitis Analysis, gait 488, 490–497 433, 434, 436, 439, 443, 464, 7 osteomyelitis, aggressive 7 Gait analysis Abduction contracture 468, 475, 485, 487–490, 493, Agonist 281, 487, 492, 493, Anchor 169, 312, 550, 734 7 contracture 496, 816, 838, 840 495, 498, 664, 832, 835, 840, Andersen classification abduction pants 219–221 – shortening 358, 418, 431, 868 7 classification, Andersen Abduction splint 212, 218–221, 433, 464, 465, 467, 468, 475, Ahn classification 366 Andry, Nicolas 21, 22 248, 850 489, 496, 838 Aitken classification (congenital Anesthesia 26, 38, 135, 154, Abduction Achondrogenesis 750, 751, femoral deficiency ) 7 classi- 162, 174, 221, 243, 247, 248, – hip 195, 198, 199, 212, 213, 756, 758–760, 769 fication, femoral deficiency 255, 281, 303, 385, 386, 400, 214, 218, 219, 220, 221, Achondroplasia 56, 163, 166, Akin osteotomy 477, 479 500, 506, 559, 568, 582–585, 241–245, 247, 248, 251, 255, 242, 270, 271, 353, 409, 628, Albers-Schönberg