Voluntary Genital Ablations: Contrasting the Cutters and Their Clients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Need of Third Gender Justice in Indian Society

IJRESS Volume 2, Issue 12 (December 2012) ISSN: 2249-7382 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND LEGAL STATUS OF THIRD GENDER IN INDIAN SOCIETY Preeti Sharma* ABSTRACT The terms third gender and third sex describe individuals who are categorized as neither man or woman as well as the social category present in those societies who recognize three or more genders. To different cultures or individuals, a third gender or six may represent an intermediate state between men and women, a state of being both. The term has been used to describe hizras of India, Bangladesh and Pakistan who have gained legal identity, Fa'afafine of Polynesia, and Sworn virgins of the Balkans, among others, and is also used by many of such groups and individuals to describe themselves like the hizra, the third gender is in many cultures made up of biological males who takes on a feminine gender or sexual role. Disowned by their families in their childhood and ridiculed and abused by everyone as ''hijra'' or third sex, eunuchs earn their livelihood by dancing at the beat of drums and often resort to obscene postures but their pain and agony is not generally noticed and this demand is just a reminder of how helpless and neglected this section of society is. Thousands of welfare schemes have been launched by the government but these are only for men and women and third sex do not figure anywhere and this demand only showed mirror to society. The Constitution gives rights on the basis of citizenship and on the grounds of gender but the gross discrimination on the part of our legislature is evident. -

Polyamory and Holy Union in Metropolitan Community Churches

Polyamory and Holy Union In Metropolitan Community Churches Frances Luella Mayes May 5, 2003 Ecumenical Theological Seminary Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Ministry Degree. Approved: Date: 5 May 2003 ___________________________________________ __________ The Rev. Dr. David Swink, D.Min., Committee Chair ___________________________________________ __________ Dr. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, Phd., Content Specialist ___________________________________________ __________ Dr. Anneliese Sinnott, Phd., O.P., Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ __________ The Rev. Paul Jaramogi, D.Min., Peer Reader Rev. Frances Mayes, MCC Holy Union All rights reserved. Frances L. Mayes, 2003 ii Rev. Frances Mayes, MCC Holy Union Abstract Metropolitan Community Churches have performed Holy Union commitment ceremonies for same-sex couples since 1969. An ongoing internal dialogue concerns whether to expand the definition to include families with more than two adult partners. This paper summarizes historical definitions of marriage and family, development of sexual theology, and current descriptions of contemporary families of varying compositions. Fourteen interviews were conducted to elicit the stories of non- monogamous MCC families. Portions of the interviews are presented as input into the discussion. iii Rev. Frances Mayes, MCC Holy Union Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the help and support given to her by the dissertation committee: Chairman Rev. Dr. David Swink, Content Specialist Dr. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, Reader Dr. Anneliese Sinnot, OP, and Peer Reader Rev. Paul Jaramogi, who nurtured this paper’s evolution. Thanks also to the Emmaus Colleague Group who patiently stood with me as my theology and practice changed and developed, and who gestated with me the four mini- project papers that preceded the dissertation. -

Part 2-Organ-Sparing Procedures in Testicular and Penile Tumors

International Urology and Nephrology (2019) 51:1699–1708 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02182-6 UROLOGY - REVIEW Organ‑sparing procedures in GU cancer: part 2‑organ‑sparing procedures in testicular and penile tumors Mohamed H. Kamel1,3 · Mahmoud I. Khalil1,3 · Ehab Eltahawy1,3 · Rodney Davis1 · Nabil K. Bissada2 Received: 1 May 2019 / Accepted: 23 May 2019 / Published online: 2 July 2019 © Springer Nature B.V. 2019 Abstract Purpose Organ-sparing surgery (OSS) is recommended in selected patients with testicular tumors and penile cancer (PC). The functional and psychological impacts of organ excision for these genital tumors are profound. In this review, we sum- marize the indications, techniques and outcomes of OSS for these two tumors. Methods PubMed® was searched for relevant articles up to December 2018. For Testicular sparing surgery (TSS) search, keywords used were; testicular tumors alone and in combination with “testicular sparing surgery”, “partial orchiectomy” and outcomes. For penile conserving surgery (PCS), keywords used were: penile cancer alone and in combination with “penile conserving surgery”, “partial penectomy” and outcomes. Because of the low quality of available evidence, a narrative rather that systematic review has been performed. Results Indications of TSS are tumors ≤ 2 cm in solitary testis or bilateral tumors and no rete testis invasion. Prerequisites include normal testosterone and luteinizing hormone levels and patient compliance with follow-up. Indications for PCS are distal penile lesions with clinical stage ≤ T1. Adequate penile stump (3 cm) is required after surgery to maintain forward urine stream. Frozen section helps to reduce the risk of recurrence. Local recurrence after PCS is not associated with reduced survival and can be managed with another PCS in selected patients. -

EAU Guidelines on Penile Cancer 2001

European Association of Urology GUIDELINES ON PENILE CANCER* F. Algaba, S. Horenblas, G. Pizzocaro, E. Solsona, T. Windahl TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Background 3 2. Classification 3 2.1 Pathology 3 2.2 References 4 3. Risk factors 5 3.1 References 5 4. Diagnosis 6 4.1 Primary lesion 6 4.2 Regional nodes 6 4.3 Distant metastases 7 4.4 Guidelines on the diagnosis of penile cancer 8 4.5 References 8 5. Treatment 9 5.1 Primary lesion 9 5.2 Regional nodes 9 5.3 Guidelines on the treatment of penile carcinoma 11 5.4 Integrated therapy 11 5.5 Distant metastases 11 5.6 Quality life 11 5.7 Technical aspects 12 5.8 Chemotherapy 12 5.9 References 14 6. Follow-up 15 6.1 Why follow-up? 15 6.2 How to follow-up 16 6.3 When to follow-up 16 6.4 Guidelines for follow-up in penile cancer 17 6.5 References 18 7. Abbreviations used in the text 19 2 1. BACKGROUND Penile carcinoma is an uncommon malignant disease with an incidence ranging from 0.1 to 7.9 per 100,000 males. In Europe, the incidence is 0.1–0.9 and in the US, 0.7–0.9 per 100,000 (1). In some areas, such as Asia, Africa and South America, penile carcinoma accounts for as many as 10–20% of male cancers. Phimosis and chronic irritation processes related to poor hygiene are commonly associated with this tumour, whereas neonatal circumcision gives protection against the disease. -

Gender Affirming Surgery and Related Procedures State(S): LOB(S): Idaho Montana Oregon Washington Other: Commercial Medicare Medicaid

Gender Affirming Surgery and Related Procedures State(s): LOB(s): Idaho Montana Oregon Washington Other: Commercial Medicare Medicaid Enterprise Policy BACKGROUND The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition (DSM 5) defines criterion A of Gender Dysphoria as “a marked incongruence between one’s experience/expressed gender and assigned gender.” These individuals must meet additional criteria which include persistence over time and clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning. Benefits must be verified by reviewing the plan’s contract or plan document (PD). Some PacificSource benefit plans do not include coverage of gender affirming surgery, procedures or other related treatment. Groups may elect to customize these benefits; therefore, benefit determinations are based on specific contract language. CRITERIA The member should be placed into case management by Health Services as a way to help the member understand their benefits and required criteria related to gender affirming surgery and treatment, and to assist her/him to navigate the system and promote an optimal outcome. Covered Services and Exclusions – Commercial, Medicaid 1. The following are considered medically necessary gender affirming surgeries. a. Core surgical procedures considered medically necessary for females transitioning to males include: hysterectomy, vaginectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, phalloplasty, urethroplasty, scrotoplasty, perineal electrolysis, and placement of testicular implant and mastectomy including nipple reconstruction. b. Core surgical procedures considered medically necessary for males transitioning to females include: penectomy, orchiectomy, vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty, perineal electrolysis, labiaplasty, and mammoplasty when 12 continuous months of hormonal (estrogen) therapy has failed to result in breast tissue growth of Tanner Stage 5 on the puberty scale or there is any contraindication to, or intolerance of, or patient refusal of hormone therapy. -

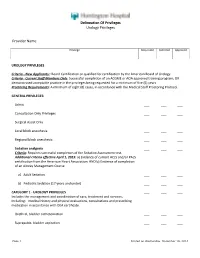

Delineation of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name

Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name: Privilege Requested Deferred Approved UROLOGY PRIVILEGES Criteria - New Applicants:: Board Certification or qualified for certification by the American Board of Urology. Criteria - Current Staff Members Only: Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA approved training program; OR demonstrated acceptable practice in the privileges being requested for a minimum of five (5) years. Proctoring Requirements: A minimum of eight (8) cases, in accordance with the Medical Staff Proctoring Protocol. GENERAL PRIVILEGES: Admit ___ ___ ___ Consultation Only Privileges ___ ___ ___ Surgical Assist Only ___ ___ ___ Local block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Regional block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Sedation analgesia ___ ___ ___ Criteria: Requires successful completion of the Sedation Assessment test. Additional criteria effective April 1, 2015: a) Evidence of current ACLS and/or PALS certification from the American Heart Association; AND b) Evidence of completion of an Airway Management Course a) Adult Sedation ___ ___ ___ b) Pediatric Sedation (17 years and under) ___ ___ ___ CATEGORY 1 - UROLOGY PRIVILEGES ___ ___ ___ Includes the management and coordination of care, treatment and services, including: medical history and physical evaluations, consultations and prescribing medication in accordance with DEA certificate. Urethral, bladder catheterization ___ ___ ___ Suprapubic, bladder aspiration ___ ___ ___ Page 1 Printed on Wednesday, December 10, 2014 Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider -

A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Subclass of Mucosal Melanoma with Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approaches

cancers Review Urological Melanoma: A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Subclass of Mucosal Melanoma with Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approaches Gerardo Cazzato 1,*,† , Anna Colagrande 1,†, Antonietta Cimmino 1, Concetta Caporusso 1, Pragnell Mary Victoria Candance 1, Senia Maria Rosaria Trabucco 1, Marcello Zingarelli 2, Alfonso Lorusso 2, Maricla Marrone 3 , Alessandra Stellacci 3 , Francesca Arezzo 4, Andrea Marzullo 1, Gabriella Serio 1, Angela Filoni 5, Domenico Bonamonte 5, Paolo Romita 5, Caterina Foti 5, Teresa Lettini 1 , Vera Loizzi 4, Gennaro Cormio 4 , Leonardo Resta 1 , Roberta Rossi 1,‡ and Giuseppe Ingravallo 1,‡ 1 Section of Pathology, Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation (DETO), University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (P.M.V.C.); [email protected] (S.M.R.T.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (G.I.) 2 Section of Urology, Deparment of Emergency and Organ Transplantation (DETO), University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (A.L.) 3 Section of Legal Medicine, Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, Bari Policlinico Hospital, Citation: Cazzato, G.; Colagrande, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Piazza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (M.M.); A.; Cimmino, A.; Caporusso, C.; [email protected] (A.S.) Candance, P.M.V.; Trabucco, S.M.R.; 4 Section of Ginecology and Obstetrics, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology, Zingarelli, M.; Lorusso, A.; Marrone, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Piazza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (F.A.); M.; Stellacci, A.; et al. -

Provider Guide

Physician-Related Services/ Health Care Professional Services Provider Guide July 1, 2015 Physician-Related Services/Health Care Professional Services About this guide* This publication takes effect July 1, 2015, and supersedes earlier guides to this program. Washington Apple Health means the public health insurance programs for eligible Washington residents. Washington Apple Health is the name used in Washington State for Medicaid, the children's health insurance program (CHIP), and state- only funded health care programs. Washington Apple Health is administered by the Washington State Health Care Authority. What has changed? Subject Change Reason for Change Medical Policy Updates Added updates from the Health Technology Clinical In accordance with WAC Committee (HTCC) 182-501-0055, the agency reviews the recommendations of HTCC and decides whether to adopt the recommendations Bariatric surgeries Removed list of agency-approved COEs and added Clarification link to web page for approved COEs Update to EPA Removed CPT 80102 CPT Code Update 870000050 Added CPT 80302 Maternity and delivery – Added intro paragraph for clarification of when to Clarification Billing with modifiers bill using modifier GB. Also updated column headers for modifiers Immune globulins Replacing deleted codes Q4087, Q4088, Q4091, and Updating deleted codes Q4092 with J1568, J1569, J1572, and J1561 Bilateral cochlear implant EPA 870001365 fixed diagnosis code 398.18 Corrected typo Newborn care The agency pays a collection fee for a newborn Clarification metabolic screening panel. The screening kit is provided free from DOH. Vaccines/Toxoids Add language “Routine vaccines are administered Clarification (Immunizations) according to current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) immunization schedule for adults and children in the United States.” Injectable and nasal flu Adding link to Injectable Fee Schedule for coverage Clarification vaccines details * This publication is a billing instruction. -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States a Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, a L Burnett, II

The Internet Journal of Law, Healthcare and Ethics ISPUB.COM Volume 11 Number 1 Penile Transplants: To Do or Not To Do: Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States A Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, A L Burnett, II Citation A Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, A L Burnett, II. Penile Transplants: To Do or Not To Do: Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States. The Internet Journal of Law, Healthcare and Ethics. 2016 Volume 11 Number 1. DOI: 10.5580/IJLHE.47425 Abstract The genitourinary injuries sustained by soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, which make urination, sexual intimacy and fathering a child, more difficult, can cause psychological distress for men, and may even lead to depression. To help ease the burden, Johns Hopkins University has approved a series of 60 experimental penile transplants on wounded veterans with such injuries following the first successful surgery in the US in May of 2016. This article addresses the permissibility of this procedure from the medical, legal, regulatory, sociocultural, religious and ethical perspectives. Medically, since penile transplant fits into the emerging new field of vascularized composite allograft (VCA) there are concerns about the risks for life-long immunosuppression, infection and malignancy. Other concerns include patient’s expectations, donor shortage and lack of public awareness. Legally, the procedure raises issues about the informed consent of donor and recipient, compliance and privacy, as well as need to require a different set of screening procedures and criteria for donation. -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

Penile Cancer

Guidelines on Penile Cancer O.W. Hakenberg (chair), E. Compérat, S. Minhas, A. Necchi, C. Protzel, N. Watkin © European Association of Urology 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Publication history 4 1.2 Potential conflict of interest statement 4 2. METHODOLOGY 4 2.1 References 5 3. DEFINITION OF PENILE CANCER 5 4. EPIDEMIOLOGY 5 4.1 References 6 5. RISK FACTORS AND PREVENTION 7 5.1 References 8 6. TNM CLASSIFICATION AND PATHOLOGY 9 6.1 TNM classification 9 6.2 Pathology 10 6.2.1 References 13 7. DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING 15 7.1 Primary lesion 15 7.2 Regional lymph nodes 15 7.2.1 Non-palpable inguinal nodes 15 7.2.2 Palpable inguinal nodes 16 7.3 Distant metastases 16 7.4 Recommendations for the diagnosis and staging of penile cancer 16 7.5 References 16 8. TREATMENT 17 8.1 Treatment of the primary tumour 17 8.1.1 Treatment of superficial non-invasive disease (CIS) 18 8.1.2 Treatment of invasive disease confined to the glans (category Ta/T1a) 18 8.1.2.1 Results of different surgical organ-preserving treatment modalities 18 8.1.2.2 Summary of results of surgical techniques 19 8.1.2.3 Results of radiotherapy for T1 and T2 disease 19 8.1.3 Treatment of invasive disease confined to the corpus spongiosum/glans (Category T2) 20 8.1.4 Treatment of disease invading the corpora cavernosa and/or urethra (category T2/T3) 20 8.1.5 Treatment of locally advanced disease invading adjacent structures (category T3/T4) 20 8.1.6 Local recurrence after organ-conserving surgery 20 8.1.7 Recommendations for stage-dependent local treatment of penile carcinoma.