EAU Guidelines on Penile Cancer 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 2-Organ-Sparing Procedures in Testicular and Penile Tumors

International Urology and Nephrology (2019) 51:1699–1708 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02182-6 UROLOGY - REVIEW Organ‑sparing procedures in GU cancer: part 2‑organ‑sparing procedures in testicular and penile tumors Mohamed H. Kamel1,3 · Mahmoud I. Khalil1,3 · Ehab Eltahawy1,3 · Rodney Davis1 · Nabil K. Bissada2 Received: 1 May 2019 / Accepted: 23 May 2019 / Published online: 2 July 2019 © Springer Nature B.V. 2019 Abstract Purpose Organ-sparing surgery (OSS) is recommended in selected patients with testicular tumors and penile cancer (PC). The functional and psychological impacts of organ excision for these genital tumors are profound. In this review, we sum- marize the indications, techniques and outcomes of OSS for these two tumors. Methods PubMed® was searched for relevant articles up to December 2018. For Testicular sparing surgery (TSS) search, keywords used were; testicular tumors alone and in combination with “testicular sparing surgery”, “partial orchiectomy” and outcomes. For penile conserving surgery (PCS), keywords used were: penile cancer alone and in combination with “penile conserving surgery”, “partial penectomy” and outcomes. Because of the low quality of available evidence, a narrative rather that systematic review has been performed. Results Indications of TSS are tumors ≤ 2 cm in solitary testis or bilateral tumors and no rete testis invasion. Prerequisites include normal testosterone and luteinizing hormone levels and patient compliance with follow-up. Indications for PCS are distal penile lesions with clinical stage ≤ T1. Adequate penile stump (3 cm) is required after surgery to maintain forward urine stream. Frozen section helps to reduce the risk of recurrence. Local recurrence after PCS is not associated with reduced survival and can be managed with another PCS in selected patients. -

Gender Affirming Surgery and Related Procedures State(S): LOB(S): Idaho Montana Oregon Washington Other: Commercial Medicare Medicaid

Gender Affirming Surgery and Related Procedures State(s): LOB(s): Idaho Montana Oregon Washington Other: Commercial Medicare Medicaid Enterprise Policy BACKGROUND The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition (DSM 5) defines criterion A of Gender Dysphoria as “a marked incongruence between one’s experience/expressed gender and assigned gender.” These individuals must meet additional criteria which include persistence over time and clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning. Benefits must be verified by reviewing the plan’s contract or plan document (PD). Some PacificSource benefit plans do not include coverage of gender affirming surgery, procedures or other related treatment. Groups may elect to customize these benefits; therefore, benefit determinations are based on specific contract language. CRITERIA The member should be placed into case management by Health Services as a way to help the member understand their benefits and required criteria related to gender affirming surgery and treatment, and to assist her/him to navigate the system and promote an optimal outcome. Covered Services and Exclusions – Commercial, Medicaid 1. The following are considered medically necessary gender affirming surgeries. a. Core surgical procedures considered medically necessary for females transitioning to males include: hysterectomy, vaginectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, phalloplasty, urethroplasty, scrotoplasty, perineal electrolysis, and placement of testicular implant and mastectomy including nipple reconstruction. b. Core surgical procedures considered medically necessary for males transitioning to females include: penectomy, orchiectomy, vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty, perineal electrolysis, labiaplasty, and mammoplasty when 12 continuous months of hormonal (estrogen) therapy has failed to result in breast tissue growth of Tanner Stage 5 on the puberty scale or there is any contraindication to, or intolerance of, or patient refusal of hormone therapy. -

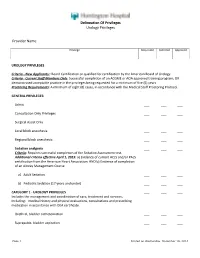

Delineation of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name

Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name: Privilege Requested Deferred Approved UROLOGY PRIVILEGES Criteria - New Applicants:: Board Certification or qualified for certification by the American Board of Urology. Criteria - Current Staff Members Only: Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA approved training program; OR demonstrated acceptable practice in the privileges being requested for a minimum of five (5) years. Proctoring Requirements: A minimum of eight (8) cases, in accordance with the Medical Staff Proctoring Protocol. GENERAL PRIVILEGES: Admit ___ ___ ___ Consultation Only Privileges ___ ___ ___ Surgical Assist Only ___ ___ ___ Local block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Regional block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Sedation analgesia ___ ___ ___ Criteria: Requires successful completion of the Sedation Assessment test. Additional criteria effective April 1, 2015: a) Evidence of current ACLS and/or PALS certification from the American Heart Association; AND b) Evidence of completion of an Airway Management Course a) Adult Sedation ___ ___ ___ b) Pediatric Sedation (17 years and under) ___ ___ ___ CATEGORY 1 - UROLOGY PRIVILEGES ___ ___ ___ Includes the management and coordination of care, treatment and services, including: medical history and physical evaluations, consultations and prescribing medication in accordance with DEA certificate. Urethral, bladder catheterization ___ ___ ___ Suprapubic, bladder aspiration ___ ___ ___ Page 1 Printed on Wednesday, December 10, 2014 Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider -

A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Subclass of Mucosal Melanoma with Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approaches

cancers Review Urological Melanoma: A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Subclass of Mucosal Melanoma with Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approaches Gerardo Cazzato 1,*,† , Anna Colagrande 1,†, Antonietta Cimmino 1, Concetta Caporusso 1, Pragnell Mary Victoria Candance 1, Senia Maria Rosaria Trabucco 1, Marcello Zingarelli 2, Alfonso Lorusso 2, Maricla Marrone 3 , Alessandra Stellacci 3 , Francesca Arezzo 4, Andrea Marzullo 1, Gabriella Serio 1, Angela Filoni 5, Domenico Bonamonte 5, Paolo Romita 5, Caterina Foti 5, Teresa Lettini 1 , Vera Loizzi 4, Gennaro Cormio 4 , Leonardo Resta 1 , Roberta Rossi 1,‡ and Giuseppe Ingravallo 1,‡ 1 Section of Pathology, Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation (DETO), University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (P.M.V.C.); [email protected] (S.M.R.T.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (G.I.) 2 Section of Urology, Deparment of Emergency and Organ Transplantation (DETO), University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (A.L.) 3 Section of Legal Medicine, Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, Bari Policlinico Hospital, Citation: Cazzato, G.; Colagrande, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Piazza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (M.M.); A.; Cimmino, A.; Caporusso, C.; [email protected] (A.S.) Candance, P.M.V.; Trabucco, S.M.R.; 4 Section of Ginecology and Obstetrics, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology, Zingarelli, M.; Lorusso, A.; Marrone, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Piazza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (F.A.); M.; Stellacci, A.; et al. -

Provider Guide

Physician-Related Services/ Health Care Professional Services Provider Guide July 1, 2015 Physician-Related Services/Health Care Professional Services About this guide* This publication takes effect July 1, 2015, and supersedes earlier guides to this program. Washington Apple Health means the public health insurance programs for eligible Washington residents. Washington Apple Health is the name used in Washington State for Medicaid, the children's health insurance program (CHIP), and state- only funded health care programs. Washington Apple Health is administered by the Washington State Health Care Authority. What has changed? Subject Change Reason for Change Medical Policy Updates Added updates from the Health Technology Clinical In accordance with WAC Committee (HTCC) 182-501-0055, the agency reviews the recommendations of HTCC and decides whether to adopt the recommendations Bariatric surgeries Removed list of agency-approved COEs and added Clarification link to web page for approved COEs Update to EPA Removed CPT 80102 CPT Code Update 870000050 Added CPT 80302 Maternity and delivery – Added intro paragraph for clarification of when to Clarification Billing with modifiers bill using modifier GB. Also updated column headers for modifiers Immune globulins Replacing deleted codes Q4087, Q4088, Q4091, and Updating deleted codes Q4092 with J1568, J1569, J1572, and J1561 Bilateral cochlear implant EPA 870001365 fixed diagnosis code 398.18 Corrected typo Newborn care The agency pays a collection fee for a newborn Clarification metabolic screening panel. The screening kit is provided free from DOH. Vaccines/Toxoids Add language “Routine vaccines are administered Clarification (Immunizations) according to current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) immunization schedule for adults and children in the United States.” Injectable and nasal flu Adding link to Injectable Fee Schedule for coverage Clarification vaccines details * This publication is a billing instruction. -

Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States a Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, a L Burnett, II

The Internet Journal of Law, Healthcare and Ethics ISPUB.COM Volume 11 Number 1 Penile Transplants: To Do or Not To Do: Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States A Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, A L Burnett, II Citation A Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, A L Burnett, II. Penile Transplants: To Do or Not To Do: Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States. The Internet Journal of Law, Healthcare and Ethics. 2016 Volume 11 Number 1. DOI: 10.5580/IJLHE.47425 Abstract The genitourinary injuries sustained by soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, which make urination, sexual intimacy and fathering a child, more difficult, can cause psychological distress for men, and may even lead to depression. To help ease the burden, Johns Hopkins University has approved a series of 60 experimental penile transplants on wounded veterans with such injuries following the first successful surgery in the US in May of 2016. This article addresses the permissibility of this procedure from the medical, legal, regulatory, sociocultural, religious and ethical perspectives. Medically, since penile transplant fits into the emerging new field of vascularized composite allograft (VCA) there are concerns about the risks for life-long immunosuppression, infection and malignancy. Other concerns include patient’s expectations, donor shortage and lack of public awareness. Legally, the procedure raises issues about the informed consent of donor and recipient, compliance and privacy, as well as need to require a different set of screening procedures and criteria for donation. -

Penile Cancer

Guidelines on Penile Cancer O.W. Hakenberg (chair), E. Compérat, S. Minhas, A. Necchi, C. Protzel, N. Watkin © European Association of Urology 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Publication history 4 1.2 Potential conflict of interest statement 4 2. METHODOLOGY 4 2.1 References 5 3. DEFINITION OF PENILE CANCER 5 4. EPIDEMIOLOGY 5 4.1 References 6 5. RISK FACTORS AND PREVENTION 7 5.1 References 8 6. TNM CLASSIFICATION AND PATHOLOGY 9 6.1 TNM classification 9 6.2 Pathology 10 6.2.1 References 13 7. DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING 15 7.1 Primary lesion 15 7.2 Regional lymph nodes 15 7.2.1 Non-palpable inguinal nodes 15 7.2.2 Palpable inguinal nodes 16 7.3 Distant metastases 16 7.4 Recommendations for the diagnosis and staging of penile cancer 16 7.5 References 16 8. TREATMENT 17 8.1 Treatment of the primary tumour 17 8.1.1 Treatment of superficial non-invasive disease (CIS) 18 8.1.2 Treatment of invasive disease confined to the glans (category Ta/T1a) 18 8.1.2.1 Results of different surgical organ-preserving treatment modalities 18 8.1.2.2 Summary of results of surgical techniques 19 8.1.2.3 Results of radiotherapy for T1 and T2 disease 19 8.1.3 Treatment of invasive disease confined to the corpus spongiosum/glans (Category T2) 20 8.1.4 Treatment of disease invading the corpora cavernosa and/or urethra (category T2/T3) 20 8.1.5 Treatment of locally advanced disease invading adjacent structures (category T3/T4) 20 8.1.6 Local recurrence after organ-conserving surgery 20 8.1.7 Recommendations for stage-dependent local treatment of penile carcinoma. -

Surgical Principles of Penile Cancer for Penectomy and Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection: a Narrative Review

11 Review Article Page 1 of 11 Surgical principles of penile cancer for penectomy and inguinal lymph node dissection: a narrative review Nathaniel D. Coddington1, Kirk D. Redger2, Ty T. Higuchi2 1Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA; 2Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: ND Coddington, TT Higuchi; (II) Administrative support: TT Higuchi; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: ND Coddington, TT Higuchi; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Ty T. Higuchi, MD. Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, University of Colorado, 12605 E. 16th Ave, Aurora, CO 80045, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Penile cancer is a rare and serious disease. Early local and regional disease is surgically curable, but advanced regional disease portends a poor prognosis—with inguinal node metastases being the most important prognostic factor. An initial histologic diagnosis with a punch, excisional, or incisional biopsy is recommended to determine the risk of lymph node involvement prior to proceeding with surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound can used adjunctively to determine the depth of invasion. Total or partial penectomy with 5mm resection margins is the standard of care for primary disease, although penile- preserving procedures—such as circumcision for preputial lesions, laser ablation, wide local excision, glans resurfacing, glansectomy, and Mohs micrographic surgery—are initially indicated for tumors of lower grade, favorable histology, and favorable location. -

CPC® Certification Review

CPC® Certification Review 1 CPT® CPT® copyright 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors and/or related components are not assigned by the AMA, are not part of CPT®, and the AMA is not recommending their use. The AMA does not directly or indirectly practice medicine or dispense medical services. The AMA assumes no liability for data contained or not contained herein. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. 2 ICD-9-CM Coding 3 NEC vs. NOS • NEC Not elsewhere classifiable “We know what’s wrong, but there isn’t a specific code for it.” • NOS Not otherwise specified “We aren’t sure what’s wrong.” 4 Punctuation [ ] Brackets: in tabular enclose synonyms or alternate wording Example: 008.0 Escherichia coli [E. coli] [ ] Slanted brackets: in index identifies manifestations and indicates sequence. Example: Diabetes, diabetic 250.0x cataract 250.5x [366.41] 5 Punctuation ( ) Parentheses: enclose supplementary words that may be present in the description Example: Cyst (mucus)(retention)(serous)(simple) 6 Additional Terms 599.0 Urinary tract infection, site not specified Excludes candidiasis of urinary tract (112.2) urinary tract infection of newborn (771.82) 280 Iron deficiency anemias anemia Includes asiderotic hypochromic-microcytic sideropenic 7 Use Additional Code 282.42 Sickle-cell thalassemia with crisis Sickle-cell thalassemia with vaso-occlusive pain Thalassemia Hb-S disease with crisis Use additional code for the type of crisis, such as: acute chest sydrome (517.3) splenic sequestration (289.52) 8 Use Additional Code, if Applicable 416.2 Chronic pulmonary embolism Use additional code, if applicable, for associated long-term (current) use of anticoagulants (V58.61) 9 Combination Codes Single codes: 787.02 Nausea alone 787.03 Vomiting alone Combination code: 787.01 Nausea with vomiting 10 Steps to Look Up a Diagnosis Code 1. -

Erectile Dysfunction and Cancer: Current Perspective

Review Article pISSN 2234-1900 · eISSN 2234-3156 Radiat Oncol J 2020;38(4):217-225 https://doi.org/10.3857/roj.2020.00332 Erectile dysfunction and cancer: current perspective Renu Madan1, Chinna Babu Dracham2, Divya Khosla1, Shikha Goyal1, Arun Kumar Yadav1 1Department of Radiotherapy and Oncology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India 2Department of Radiation Oncology, Queen’s NRI Hospital, Visakhapatnam, India Received: June 3, 2020 Revised: July 19, 2020 Erectile dysfunction (ED) is one of the major but underreported concerns in cancer patients and survi- Accepted: July 30, 2020 vors. It can lead to depression, lack of intimacy between the couple, and impaired quality of life. The causes of erectile dysfunction are psychological distress and endocrinal dysfunction caused by cancer Correspondence: itself or side effect of anticancer treatment like surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and hormonal Chinna Babu Dracham therapy. The degree of ED depends on age, pre-cancer or pre-treatment potency level, comorbidities, Department of Radiation Oncology, type of cancer and its treatment. Treatment options available for ED are various pharmacotherapies, Queen’s NRI Hospital, mechanical devices, penile implants, or reconstructive surgeries. A complete evaluation of sexual Seethammadhara, Gurudwara lane, functioning should be done before starting anticancer therapy. Management should be individualized Visakhapatnam 530013, India and couple counseling should be an integral part of the anticancer treatment. Tel: +91-9855803437 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Erectile dysfunction, Neoplasm, Surgery, Radiotherapy ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8921-0957 Introduction androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and RP (with or without nerve sparing) was associated with higher incidence of sexual dysfunc- Cancer diagnosis and its management lead to physical and emo- tion. -

Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Clinical Practice Guidelines

PRINCESS MARGARET CANCER CENTRE CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES GENITOURINARY UROTHELIAL CANCER GU Site Group – Urothelial Cancer Date Guideline Created: March 2012 Author: Dr. Charles Catton 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. PREVENTION 3 3. SCREENING AND EARLY DETECTION 3 4. DIAGNOSIS 3 5. PATHOLOGY 5 6. MANAGEMENT 6 6.1 PRIMARY PRESENTATION NON-MUSCLE INVASIVE BLADDER DISEASE 6 6.2 RECURRENT PRESENTATION NON-MUSCLE INVASIVE BLADDER DISEASE 6 6.3 MUSCLE INVASIVE BLADDER DISEASE 7 6.4 METASTATIC TCC 10 6.5 MANAGEMENT OF PROGRESSION AFTER INITIAL THERAPY 10 6.6 EXRAVESICAL TCC 11 6.7 ADENOCARCINOMA OF THE BLADDER 12 6.8 ONCOLOGY NURSING PRACTICE 13 7. SUPPORTIVE CARE 13 7.1 PATIENT EDUCATION 13 7.2 PSYCHOSOCIAL CARE 13 7.3 SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT 13 7.4 CLINICAL NUTRITION 14 7.5 PALLIATIVE CARE 14 7.6 OTHER 14 8. FOLLOW-UP CARE 14 9. APPENDIX 1 – PATHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION 16 10. APPENDIX 2 – BLADDER CANCER STAGING 19 2 Last Revision Date – March 2012 1. INTRODUCTION Urothelial cancers arise in the urothelium of the renal collecting systems, the ureters, bladder, prostate and urethra. The bladder is the most frequent site of disease accounting in Canada for 5.8% of new cancers and 3.3% of cancer deaths in males, and 2.1% of new cancers and 1.5% of cancer deaths in females (Canadian Cancer Statistics 2008). This difference in incidence is attributed in part to the smoking patterns seen between Canadian men and women. The most common histology is transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). An important feature of transitional cell malignancy is the propensity to behave as a field defect with multifocal disease in primary and recurrent presentations. -

Department of Urology

07/21/2020 www.ucsfmedicalcenter.org/medstaffoffice/privilege_form.asp?LINK=995 www.ucsfmedicalcenter.org/medstaffoffice/privilege_form.asp?LINK=995 Department of Urology CAT 1 Basic Privileges: Patient management including H & Ps and diagnostic and therapeutic treatments, procedures and interventions encompassing the areas described below and similar activities Requiring a level of training generally associated with persons who have completed the residency program prescribed by the American Board of Urology, and a level of skill and ability generally associated with persons who are diplomates of that board. A) Diagnosis and treatment of diseases and abnormalities of the female urinary tract and the male urogenital tract, including administration of topical and local anesthesia. Includes minor urologic procedures such as dorsal slit, circumcision, biopsymeatotomy, and vasectomy. CAT 2 Subspecialty Privileges: Patient management at this level encompasses the items marked below, and similar activities Requiring a level of training, skill and ability generally associated with persons who are diplomates of the American Board of Urology and who have had additional training and/or experience in specific patient management problems and specialized expertise and training in order to perform the procedures A) Radical procedures such as radical cystectomy, radical prostatectomy, radical penectomy, radical nephrectomy, lymphadenectomy, extenterations, laparoscopic and percutaneous procedures, laser and renovascular surgery. B) Renal transplantation CAT 3 Special Privileges: Patient management at this level encompasses the items marked below, and similar activities Requiring a level of training, skill and ability generally associated with persons who are diplomates of the American Board of Urology and who have had additional training and/or experience in specific patient management problems.