Penile Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 2-Organ-Sparing Procedures in Testicular and Penile Tumors

International Urology and Nephrology (2019) 51:1699–1708 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02182-6 UROLOGY - REVIEW Organ‑sparing procedures in GU cancer: part 2‑organ‑sparing procedures in testicular and penile tumors Mohamed H. Kamel1,3 · Mahmoud I. Khalil1,3 · Ehab Eltahawy1,3 · Rodney Davis1 · Nabil K. Bissada2 Received: 1 May 2019 / Accepted: 23 May 2019 / Published online: 2 July 2019 © Springer Nature B.V. 2019 Abstract Purpose Organ-sparing surgery (OSS) is recommended in selected patients with testicular tumors and penile cancer (PC). The functional and psychological impacts of organ excision for these genital tumors are profound. In this review, we sum- marize the indications, techniques and outcomes of OSS for these two tumors. Methods PubMed® was searched for relevant articles up to December 2018. For Testicular sparing surgery (TSS) search, keywords used were; testicular tumors alone and in combination with “testicular sparing surgery”, “partial orchiectomy” and outcomes. For penile conserving surgery (PCS), keywords used were: penile cancer alone and in combination with “penile conserving surgery”, “partial penectomy” and outcomes. Because of the low quality of available evidence, a narrative rather that systematic review has been performed. Results Indications of TSS are tumors ≤ 2 cm in solitary testis or bilateral tumors and no rete testis invasion. Prerequisites include normal testosterone and luteinizing hormone levels and patient compliance with follow-up. Indications for PCS are distal penile lesions with clinical stage ≤ T1. Adequate penile stump (3 cm) is required after surgery to maintain forward urine stream. Frozen section helps to reduce the risk of recurrence. Local recurrence after PCS is not associated with reduced survival and can be managed with another PCS in selected patients. -

EAU Guidelines on Penile Cancer 2001

European Association of Urology GUIDELINES ON PENILE CANCER* F. Algaba, S. Horenblas, G. Pizzocaro, E. Solsona, T. Windahl TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Background 3 2. Classification 3 2.1 Pathology 3 2.2 References 4 3. Risk factors 5 3.1 References 5 4. Diagnosis 6 4.1 Primary lesion 6 4.2 Regional nodes 6 4.3 Distant metastases 7 4.4 Guidelines on the diagnosis of penile cancer 8 4.5 References 8 5. Treatment 9 5.1 Primary lesion 9 5.2 Regional nodes 9 5.3 Guidelines on the treatment of penile carcinoma 11 5.4 Integrated therapy 11 5.5 Distant metastases 11 5.6 Quality life 11 5.7 Technical aspects 12 5.8 Chemotherapy 12 5.9 References 14 6. Follow-up 15 6.1 Why follow-up? 15 6.2 How to follow-up 16 6.3 When to follow-up 16 6.4 Guidelines for follow-up in penile cancer 17 6.5 References 18 7. Abbreviations used in the text 19 2 1. BACKGROUND Penile carcinoma is an uncommon malignant disease with an incidence ranging from 0.1 to 7.9 per 100,000 males. In Europe, the incidence is 0.1–0.9 and in the US, 0.7–0.9 per 100,000 (1). In some areas, such as Asia, Africa and South America, penile carcinoma accounts for as many as 10–20% of male cancers. Phimosis and chronic irritation processes related to poor hygiene are commonly associated with this tumour, whereas neonatal circumcision gives protection against the disease. -

Gender Affirming Surgery and Related Procedures State(S): LOB(S): Idaho Montana Oregon Washington Other: Commercial Medicare Medicaid

Gender Affirming Surgery and Related Procedures State(s): LOB(s): Idaho Montana Oregon Washington Other: Commercial Medicare Medicaid Enterprise Policy BACKGROUND The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition (DSM 5) defines criterion A of Gender Dysphoria as “a marked incongruence between one’s experience/expressed gender and assigned gender.” These individuals must meet additional criteria which include persistence over time and clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning. Benefits must be verified by reviewing the plan’s contract or plan document (PD). Some PacificSource benefit plans do not include coverage of gender affirming surgery, procedures or other related treatment. Groups may elect to customize these benefits; therefore, benefit determinations are based on specific contract language. CRITERIA The member should be placed into case management by Health Services as a way to help the member understand their benefits and required criteria related to gender affirming surgery and treatment, and to assist her/him to navigate the system and promote an optimal outcome. Covered Services and Exclusions – Commercial, Medicaid 1. The following are considered medically necessary gender affirming surgeries. a. Core surgical procedures considered medically necessary for females transitioning to males include: hysterectomy, vaginectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, phalloplasty, urethroplasty, scrotoplasty, perineal electrolysis, and placement of testicular implant and mastectomy including nipple reconstruction. b. Core surgical procedures considered medically necessary for males transitioning to females include: penectomy, orchiectomy, vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty, perineal electrolysis, labiaplasty, and mammoplasty when 12 continuous months of hormonal (estrogen) therapy has failed to result in breast tissue growth of Tanner Stage 5 on the puberty scale or there is any contraindication to, or intolerance of, or patient refusal of hormone therapy. -

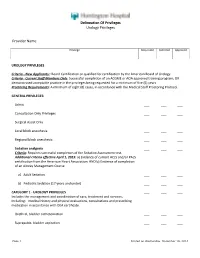

Delineation of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name

Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name: Privilege Requested Deferred Approved UROLOGY PRIVILEGES Criteria - New Applicants:: Board Certification or qualified for certification by the American Board of Urology. Criteria - Current Staff Members Only: Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA approved training program; OR demonstrated acceptable practice in the privileges being requested for a minimum of five (5) years. Proctoring Requirements: A minimum of eight (8) cases, in accordance with the Medical Staff Proctoring Protocol. GENERAL PRIVILEGES: Admit ___ ___ ___ Consultation Only Privileges ___ ___ ___ Surgical Assist Only ___ ___ ___ Local block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Regional block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Sedation analgesia ___ ___ ___ Criteria: Requires successful completion of the Sedation Assessment test. Additional criteria effective April 1, 2015: a) Evidence of current ACLS and/or PALS certification from the American Heart Association; AND b) Evidence of completion of an Airway Management Course a) Adult Sedation ___ ___ ___ b) Pediatric Sedation (17 years and under) ___ ___ ___ CATEGORY 1 - UROLOGY PRIVILEGES ___ ___ ___ Includes the management and coordination of care, treatment and services, including: medical history and physical evaluations, consultations and prescribing medication in accordance with DEA certificate. Urethral, bladder catheterization ___ ___ ___ Suprapubic, bladder aspiration ___ ___ ___ Page 1 Printed on Wednesday, December 10, 2014 Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider -

A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Subclass of Mucosal Melanoma with Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approaches

cancers Review Urological Melanoma: A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Subclass of Mucosal Melanoma with Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approaches Gerardo Cazzato 1,*,† , Anna Colagrande 1,†, Antonietta Cimmino 1, Concetta Caporusso 1, Pragnell Mary Victoria Candance 1, Senia Maria Rosaria Trabucco 1, Marcello Zingarelli 2, Alfonso Lorusso 2, Maricla Marrone 3 , Alessandra Stellacci 3 , Francesca Arezzo 4, Andrea Marzullo 1, Gabriella Serio 1, Angela Filoni 5, Domenico Bonamonte 5, Paolo Romita 5, Caterina Foti 5, Teresa Lettini 1 , Vera Loizzi 4, Gennaro Cormio 4 , Leonardo Resta 1 , Roberta Rossi 1,‡ and Giuseppe Ingravallo 1,‡ 1 Section of Pathology, Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation (DETO), University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (P.M.V.C.); [email protected] (S.M.R.T.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (G.I.) 2 Section of Urology, Deparment of Emergency and Organ Transplantation (DETO), University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (A.L.) 3 Section of Legal Medicine, Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, Bari Policlinico Hospital, Citation: Cazzato, G.; Colagrande, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Piazza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (M.M.); A.; Cimmino, A.; Caporusso, C.; [email protected] (A.S.) Candance, P.M.V.; Trabucco, S.M.R.; 4 Section of Ginecology and Obstetrics, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology, Zingarelli, M.; Lorusso, A.; Marrone, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Piazza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (F.A.); M.; Stellacci, A.; et al. -

Provider Guide

Physician-Related Services/ Health Care Professional Services Provider Guide July 1, 2015 Physician-Related Services/Health Care Professional Services About this guide* This publication takes effect July 1, 2015, and supersedes earlier guides to this program. Washington Apple Health means the public health insurance programs for eligible Washington residents. Washington Apple Health is the name used in Washington State for Medicaid, the children's health insurance program (CHIP), and state- only funded health care programs. Washington Apple Health is administered by the Washington State Health Care Authority. What has changed? Subject Change Reason for Change Medical Policy Updates Added updates from the Health Technology Clinical In accordance with WAC Committee (HTCC) 182-501-0055, the agency reviews the recommendations of HTCC and decides whether to adopt the recommendations Bariatric surgeries Removed list of agency-approved COEs and added Clarification link to web page for approved COEs Update to EPA Removed CPT 80102 CPT Code Update 870000050 Added CPT 80302 Maternity and delivery – Added intro paragraph for clarification of when to Clarification Billing with modifiers bill using modifier GB. Also updated column headers for modifiers Immune globulins Replacing deleted codes Q4087, Q4088, Q4091, and Updating deleted codes Q4092 with J1568, J1569, J1572, and J1561 Bilateral cochlear implant EPA 870001365 fixed diagnosis code 398.18 Corrected typo Newborn care The agency pays a collection fee for a newborn Clarification metabolic screening panel. The screening kit is provided free from DOH. Vaccines/Toxoids Add language “Routine vaccines are administered Clarification (Immunizations) according to current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) immunization schedule for adults and children in the United States.” Injectable and nasal flu Adding link to Injectable Fee Schedule for coverage Clarification vaccines details * This publication is a billing instruction. -

Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States a Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, a L Burnett, II

The Internet Journal of Law, Healthcare and Ethics ISPUB.COM Volume 11 Number 1 Penile Transplants: To Do or Not To Do: Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States A Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, A L Burnett, II Citation A Ochasi, N Sopko, G Mamo, V Pepe, A L Burnett, II. Penile Transplants: To Do or Not To Do: Medical, Legal, Psychosocial, and Ethical Issues of Penile Transplants for Injured Veterans in the United States. The Internet Journal of Law, Healthcare and Ethics. 2016 Volume 11 Number 1. DOI: 10.5580/IJLHE.47425 Abstract The genitourinary injuries sustained by soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, which make urination, sexual intimacy and fathering a child, more difficult, can cause psychological distress for men, and may even lead to depression. To help ease the burden, Johns Hopkins University has approved a series of 60 experimental penile transplants on wounded veterans with such injuries following the first successful surgery in the US in May of 2016. This article addresses the permissibility of this procedure from the medical, legal, regulatory, sociocultural, religious and ethical perspectives. Medically, since penile transplant fits into the emerging new field of vascularized composite allograft (VCA) there are concerns about the risks for life-long immunosuppression, infection and malignancy. Other concerns include patient’s expectations, donor shortage and lack of public awareness. Legally, the procedure raises issues about the informed consent of donor and recipient, compliance and privacy, as well as need to require a different set of screening procedures and criteria for donation. -

Highlighting the Importance of Sexually Transmitted Disease Testing Upon Diagnosis of Penile Cancer: a Case Report

Case Study Clinical Case Reports International Published: 15 Jun, 2020 Highlighting the Importance of Sexually Transmitted Disease Testing Upon Diagnosis of Penile Cancer: A Case Report Médina Ndoye1, Lissoune Cisse1, Mark LaGreca2, Timothy Phillips2, Mark Siden2* and Matthew Weaver2 1Department of Urology, Idrissa Pouye General Hospital, Senegal 2Department of Medicine, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, USA Abstract There is a well-known association between Human Papillomavirus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus with penile cancer. Yet, it is not the standard of care to screen for either of these sexually transmitted diseases upon diagnosis of primary penile cancer. We present a 50 year old male who had a confirmed diagnosis of penile cancer for 2 years prior to his presentation to our clinic in Dakar, Senegal. Outside institutions repeatedly failed to screen the patient for sexually transmitted diseases, namely HPV and HIV. We share this case to emphasize the importance of sexually transmitted disease screening upon diagnosis of penile cancer with hopes to increase awareness in both developed and developing nations. We call for consensus in sexually transmitted disease screening guidelines upon penile cancer diagnoses. Keywords: Penile cancer; HPV; HIV; STD screening Introduction Primary penile cancer is a rare malignant overgrowth of cells, typically located on the glans or the internal prepuce of the penis. It has a worldwide incidence of 1/100,000 and most commonly affects males between the ages of 50 years to 70 years. Delayed diagnosis often yields significant OPEN ACCESS morbidity and mortality [1,2]. While penile cancer is uncommon in Europe and North America, the developing world has much higher rates of incidence up to 8 cases per 100,000 in some countries *Correspondence: [3]. -

A Current Update on Human Papillomavirus-Associated Head and Neck Cancers

viruses Review A Current Update on Human Papillomavirus-Associated Head and Neck Cancers Ebenezer Tumban Department of Biological Sciences, Michigan Technological University, 1400 Townsend Dr, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-906-487-2256; Fax: +1-906-487-3167 Received: 16 September 2019; Accepted: 4 October 2019; Published: 9 October 2019 Abstract: Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the cause of a growing percentage of head and neck cancers (HNC); primarily, a subset of oral squamous cell carcinoma, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. The majority of HPV-associated head and neck cancers (HPV + HNC) are caused by HPV16; additionally, co-factors such as smoking and immunosuppression contribute to the progression of HPV + HNC by interfering with tumor suppressor miRNA and impairing mediators of the immune system. This review summarizes current studies on HPV + HNC, ranging from potential modes of oral transmission of HPV (sexual, self-inoculation, vertical and horizontal transmissions), discrepancy in the distribution of HPV + HNC between anatomical sites in the head and neck region, and to studies showing that HPV vaccines have the potential to protect against oral HPV infection (especially against the HPV types included in the vaccines). The review concludes with a discussion of major challenges in the field and prospects for the future: challenges in diagnosing HPV + HNC at early stages of the disease, measures to reduce discrepancy in the prevalence of HPV + HNC cases between anatomical sites, and suggestions to assess whether fomites/breast milk can transmit HPV to the oral cavity. Keywords: HPV; oral transmission; head and neck cancers; HPV vaccines; HIV and AIDS; head and neck cancer treatment 1. -

Penile Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Penile Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis Finding cancer early, when it's small and before it has spread, often allows for more treatment options. Some early cancers may have signs and symptoms that can be noticed, but that's not always the case. ● Can Penile Cancer Be Found Early? ● Signs and Symptoms of Penile Cancer ● Tests for Penile Cancer Stages of Penile Cancer After a cancer diagnosis, staging provides important information about the extent of cancer in the body and the likely response to treatment. ● Penile Cancer Stages Outlook (Prognosis) Doctors often use survival rates as a standard way of discussing a person's outlook (prognosis). These numbers can’t tell you how long you will live, but they might help you better understand your prognosis. Some people want to know the survival statistics for people in similar situations, while others might not find the numbers helpful, or might even not want to know them. ● Survival Rates for Penile Cancer 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Questions to Ask About Penile Cancer Here are some questions you can ask your cancer care team to help you better understand your cancer diagnosis and treatment options. ● Questions To Ask About Penile Cancer Can Penile Cancer Be Found Early? There are no widely recommended screening tests for penile cancer, but many penile cancers can be found early, when they're small and before they have spread to other parts of the body. Almost all penile cancers start in the skin, so they're often noticed early. -

NCCN Guidelines for Penile Cancer from Version 1.2019 Include

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Penile Cancer Version 2.2019 — May 13, 2019 NCCN.org Continue Version 2.2019, 05/13/19 © 2019 National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®), All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN. NCCN Guidelines Index NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2019 Table of Contents Penile Cancer Discussion *Thomas W. Flaig, MD †/Chair Harry W. Herr, MD ϖ Sumanta K. Pal, MD † University of Colorado Cancer Center Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center City of Hope National Medical Center *Philippe E. Spiess, MD, MS ϖ/Vice Chair Christopher Hoimes, MD † Anthony Patterson, MD ϖ Moffitt Cancer Center Case Comprehensive Cancer Center/ St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/ University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center The University of Tennessee Neeraj Agarwal, MD ‡ † and Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute Health Science Center Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah Brant A. Inman, MD, MSc ϖ Elizabeth R. Plimack, MD, MS † Duke Cancer Institute Fox Chase Cancer Center Rick Bangs, MBA Patient Advocate Masahito Jimbo, MD, PhD, MPH Þ Kamal S. Pohar, MD ϖ University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center The Ohio State University Comprehensive Stephen A. Boorjian, MD ϖ Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital Mayo Clinic Cancer Center A. Karim Kader, MD, PhD ϖ and Solove Research Institute UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center Mark K. Buyyounouski, MD, MS § Michael P. Porter, MD, MS ϖ Stanford Cancer Institute Subodh M. Lele, MD ≠ Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/ Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Sam Chang, MD ¶ Seattle Cancer Care Alliance Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center Joshua J. -

Prognostic Significance of HPV and P16 Status in Men Diagnosed with Penile Cancer: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Published OnlineFirst July 9, 2018; DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0322 Review Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers Prognostic Significance of HPV and p16 Status in & Prevention Men Diagnosed with Penile Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Freja Lærke Sand1, Christina Louise Rasmussen1, Marie Hoffmann Frederiksen2, Klaus Kaae Andersen2, and Susanne K. Kjaer1,3 Abstract It has been shown that human papillomavirus (HPV) of DSS, we included 649 men with penile cancer tested for and p16 status has prognostic value in some HPV-associ- HPV (27% were HPV-positive) and 404 men tested for p16 ated cancers. However, studies examining survival in men expression (47% were p16-positive). The pooled HRHPV of with penile cancer according to HPV or p16 status are often DSS was 0.61 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.38–0.98], inconclusive, mainly because of small study populations. andthepooledHRp16 of DSS was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.30– The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to 0.69). In conclusion, men with HPV or p16-positive penile examine the association between HPV DNA and p16 status cancer have a significantly more favorable DSS compared and survival in men diagnosed with penile cancer. Multi- with men with HPV or p16-negative penile cancer. These ple electronic databases were searched. Twenty studies findings point to the possible clinical value of HPV and were ultimately included and study-specific and pooled p16 testing when planning the most optimal management HRs of overall survival and disease-specific survival (DSS) and follow-up strategy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev; 27(10); 1– were calculated using a fixed effects model.